British Uruguayans

British Uruguayans (sometimes known as Anglo-Uruguayans) are British nationals residing permanently in Uruguay or Uruguayan citizens claiming British heritage. Unlike other waves of immigration to Uruguay from Europe, British immigration to Uruguay has historically been small, especially when compared to the influxes of Spanish and Italian immigrants. Like their counterparts in Argentina, British immigrants tended to be skilled workers, ranchers, businessmen and bureaucrats rather than those escaping poverty in their homeland.[lower-alpha 1]

| |

|---|---|

Holy Trinity Church, known locally as Templo Inglés, built in 1844 to cater to the British community | |

| Total population | |

| c. 4500+ (Thousands with British ancestry) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Throughout Uruguay. Principally in the south and in the west. | |

| Languages | |

| Rioplatense Spanish and English | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| English Argentine |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| British Latin Americans |

|---|

| Groups |

| Languages |

The British in Uruguay were highly influential during the height of the Victorian era, to the extent that Uruguay came to be described as an informal colony. They were intimately involved with the industrialisation of the Uruguayan economy and in the promotion of competitive sports such as rugby, cricket, and most notably, football. However, dissatisfaction with the performance of British monopolies like the Central Uruguay Railway and the Montevideo Waterworks Company found a popular outlet in the ideology of Batllismo; this, combined with Britain's decline as a great power, gradually eroded the sway that British governments had traditionally enjoyed in Uruguay.

Consequently, British immigration declined from an already low base, and the existing British community steadily integrated with the wider population as the 20th century progressed. In more recent years, Uruguay has become an increasingly popular destination for British expats due to its "European feel", low taxes and cheap healthcare.[2]

Profile

It is unclear how many British nationals or descendants of British people reside in Uruguay, and estimates vary depending on how strictly the British community in Uruguay is defined.

In 2006, 690 British citizens resided in Uruguay, 40 of whom were pensioners.[3] Regarding non-citizens, the 1996 census showed 509 permanent residents in Uruguay who were born in the United Kingdom.[4] This figure had declined to 269 by the 2011 census.[4] A 2013 article in the paper El Observador reported an active "English community" of around 4,500, including both descendants and those born in the United Kingdom.[5]

History

Background

In February 1807, following their victory at Cardal, the British Army captured Montevideo and occupied the city for several months as part of their ultimately failed Campaign in the River Plate.[lower-alpha 2] While brief, the occupation was arguably a "commercial success" and foreshadowed the close economic relationship Uruguay and the United Kingdom later developed.[7] As summarised by the travel writer William Henry Koebel, the local merchant class appreciated the liberal trading regime overseen by the occupiers:

Not only had the inhabitants of the provinces learned their own power, but — more especially in the case of Montevideo — the seeds of commercial liberty had been sown amongst the local merchants and traders by the English men of business who had descended upon the place beneath the protection of the army.

— W. H. Koebel, Uruguay (1923), p. 55[8]

In 1824 mercantile elites in Montevideo lobbied to have the Banda Oriental become a British colony.[9] This was rejected, although Lord Ponsonby encouraged them to believe that an independent Uruguay would be protected by Britain and receive British capital and skilled migrants.[9] The Empire of Brazil sought to incorporate Uruguay into its own territory as Cisplatina and fought against the insurrectionist forces of the Thirty-Three Orientals and their allies, the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. In 1828, British mediation produced the Treaty of Montevideo, which cemented Uruguay as a buffer state neither Brazil or Argentina would control.[9]

Early history

To cater to the needs of the fledgling British community in its early years, the British Cemetery was established on land purchased by the British government. Businessman Samuel Fisher Lafone financed the construction of the Anglican Holy Trinity Church, completed in 1844. Economic development was obstructed during this time by the Uruguayan Civil War (1838–1851), but in its aftermath the country attracted greater immigration and investment thanks to the growth of wool and cattle production.[10]

At first, British citizens came to Uruguay mainly to work on the ranches, often as owners of their own estancias.[11] As a group, British landowners in rural Uruguay were few in number though highly influential. They were "modernizers" who imported pedigree livestock and erected wire fencing to mark their property.[10][lower-alpha 3] Another wave of immigration was inspired by the growth of the British textile industry: its insatiable demand for imported wool was the catalyst for an influx of sheep ranchers from Britain.[12] After 1870, Uruguay had more sheep than cattle.[12]

In all, British ranchers in Uruguay were at the "vanguard of a new rural upper-class" that developed from the 1860s onwards.[13] They thrived thanks to a combination of technical knowledge, entrepreneurial spirit, and a strongly capitalist mentality.[13][lower-alpha 4] According to historian Alvaro Cuenca, British settlers during the first decades of independence tended to be "businessmen and adventurers, and usually some combination of both".[14] An example is Richard Bannister Hughes. He founded one of the first tourist estancias, Estancia La Paz, in 1856, and in 1859 set up a meat-salting business at Villa Independencia, a location that became synonymous with meat processing under its later name of Fray Bentos.[15]

In 1865 the first railroads were constructed in Montevideo.[16] This was a turning point both for the Uruguayan economy and immigration patterns. The national expansion of the rail network in the coming decades altered Uruguay's economic geography decisively in favour of Montevideo — a port city where all rail networks lead for export of products, many of which were destined for Britain.[17] Notably, meat-packing technology arrived in the 1860s, which allowed the canning of meat for export.[12][lower-alpha 5]

Apex

The British, along with German and French immigrants, impacted changes in family structure during the 19th and 20th centuries. Since a large portion of the higher-status migrants tended to be from Northern Europe, they introduced their small family tradition; and urban Uruguayans further down the social spectrum were prone to imitating the customs, habits, and lifestyles of the social elite.[18] By 1909, the average family had only three children, and many had fewer.[18]

Eased by the spread of the railroads, Britain significantly increased its investment in Uruguay in the decades following the civil war. The pattern of British settlement gradually shifted away from the interior, and rural economic hubs like Colonia del Sacramento became less important.[19] Eventually, the main group of incomers were administrators and technicians employed by British companies in Montevideo.[11] The British in Uruguay held significant economic power, and so deep was the extent of British investment that Uruguay's public debt was held in London.[14] By the eve of World War I the railway system was owned and operated by British companies, and public utilities in Montevideo were either British monopolies or dominated by British capital; including gas, water supply, trams and telephones.[20] Half the foreign shipping tonnage entering Montevideo was British.[20]

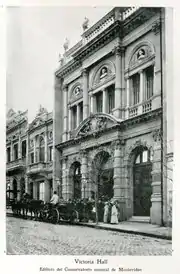

British nationals moved to Uruguay to help manage these interests and a number of institutions were launched to service their needs, such as The British Schools of Montevideo; the Victoria Hall theatre, The Montevideo Times newspaper (1892–1934), and the British Hospital.[14][lower-alpha 6] In general, British immigrants succeeded in constructing a home away from home. They reproduced the Victorian values and "rigid protocol and etiquette" of the society from which they came.[22] Despite this, adaptation to native customs was not unheard of.[22] The community of British railroad employees in working-class Peñarol took part enthusiastically in the local carnival, with an Englishwoman once taking first prize in the costume contest.[22]

Estimates vary as to the size and composition of the British community in Uruguay as the United Kingdom approached the height of its influence. A contemporary figure of 4,000 was noted in a January 1889 diary entry written by the diplomat Ernest Satow, who also recorded 1,200 Britons in Montevideo as the single biggest group.[23] Cuenca prefers a more conservative estimate of 2,000 nationwide for the last decade of the 19th century, and argues that the vast majority were concentrated in Montevideo, where they lived and worked in the same neighbourhoods.[14]

Decline

As the empire declined in the 20th century so too did British power in Uruguay.[14] British investment had reached its peak by 1914. Although Uruguay had been "born and raised under British tutelage", ties were now loosening and from then on a diminishing proportion of exports was directed to the United Kingdom.[24] Meanwhile, complaints over the inadequate and expensive services provided by British-owned public utilities — already a matter of general comment before the end of the 19th century — were reaching a crescendo.[25] Uruguay's position in the "imperial system" also failed to serve the interests of an aspiring middle-class, whose desire for social improvement was undermined by foreign companies recruiting mainly from their own countries. Political backlash was inevitable.[26]

The reformist politics of President José Batlle y Ordóñez clashed with British commercial interests; his power base consisting of small producers and immigrant labourers in urban Montevideo.[10] Batlle was sympathetic to state enterprise and his support for striking workers made him a "socialist menace" in the eyes of the British Foreign Office.[lower-alpha 7] The dominance of Britain was further weakened by German and American competition, while the emergence of refrigeration (Uruguay sent its first shipment of frozen beef in 1905) allowed access to more export markets.[27] Nevertheless, Britain retained some leverage despite the drying up of British capital, as it remained the principal market for chilled and frozen meat.[10]

Integration

In 1935 Uruguay signed a pact with Britain, agreeing to pay debt, purchase British coal, and treat British companies generously, with the British government ensuring the placement of Uruguayan products in return.[28] However, the 1940s proved to be the last decade of the special relationship between Britain and Uruguay.[10] With the onset of the Second World War, Britain struggled to pay for meat imports it received from Uruguay, and in 1947 arranged to transfer ownership of railways, trams and waterworks to the Uruguayan government in exchange for cancellation of the remaining payments.[10] The United States superseded the United Kingdom as principal supplier in the aftermath, although Britain would stay as a major market for Uruguayan exports.[29] As a sign of the changing times, Uruguay switched to driving on the right, having initially driven on the left in the British fashion.[30]

Approximately 250 Anglo-Uruguayans fought for the British during the war, but by now they were "practically as criollo" as the natives.[14] Nevertheless, a small English-speaking community remained in Montevideo. It was complemented by legacy institutions like schools and social clubs and, for a time, was strong enough to support English-language newsletters.[31] The last English language newspaper, The Montevidean, was founded in 1951 and appeared bi-weekly.[32] Other than reporting on the social activities of British residents, it expressed a consistently right-wing political stance characterised by loyalty to Empire, anti-communism, hostility to Juan Perón, and concern over the high inflation that then troubled Uruguay.[32] Due to declining interest it shortened the length of its issues before ending publication in November 1969.[32] Such was the speed of integration that by the 1970s the number of people in Uruguay living in "distinctly ethnic communities" was minimal.[31]

Culture

Clubs

The British Society in Uruguay was founded in 1918 as an umbrella organization to represent the interests of British expatriates and Anglo-Uruguayans.[33] As of May 2021, it held a membership of 440. The British Society also manages a charitable fund, a beneficiary of which is a nursing home, the Sir Winston Churchill Home.[34] It stresses it has a broad definition of "British community" and prospective members do not necessarily need any British ancestry, only an interest in society activities.[34] There is a physical location for the society at the former British Cemetery custodian's house.[34]

Freemasonry is historically associated with the British community in Uruguay and during the 1920s it was estimated that 60% of British men living in Montevideo were active masons.[35] One of the British lodges, Silver River Lodge, remains active and meets at the William G. Best Masonic Temple.[36]

Sport

Many sports in Uruguay were initiated by British immigrants before spreading to the wider population. British seamen introduced football to the River Plate region in the 1860s. It was reportedly being played in the streets of Buenos Aires by 1864 and soon made its way to nearby Montevideo.[6] In 1891, Albion F.C. was formed as the first sports club in Uruguay based entirely on football.[38] Rugby arrived at around the same time, but unlike football, it has remained a minority pursuit played mainly in the "wealthier Anglophile suburbs" like Carrasco.[39]

Montevideo Cricket Club was founded by English immigrants in 1861 and is the oldest sports club in both Uruguay and South America.[40] Despite its name the club soon accommodated other sports and is now better known for rugby than the sport it was originally intended for.[40][39] Polo was a later arrival — the first game in Uruguay in which British riders are known to have participated took place in the British enclave of San Jorge in 1897.[37]

Ana María Rodríguez, a Uruguayan historian, has described how these sporting activities reflected a desire on the part of the British to "carry a portion of their homeland with them" in order to feel more comfortable in a foreign land.[41] These efforts even extended to fox hunting, which British ranchers in the Río Negro Department repeatedly attempted using local dogs.[42] The notion of social exclusivity was often part of the appeal: when Montevideo Rowing Club started in 1872 the original club laws extended membership only to Englishmen and the sons of Englishmen.[42] Furthermore, as football developed into a sport with mass popularity in Uruguay, wealthier Anglo-Uruguayans began to lose interest.[42]

Settlements

Interior

Conchillas and Barker in the Colonia Department, and San Jorge in the Durazno Department are examples of British settlements established in the interior of Uruguay during the late 19th century. San Jorge is a good example of modernization applied to the countryside: here private property was secured with wire fencing, a flour mill was built, and afforestation was initiated to secure more space for cattle breeding.[37]

Conchillas in particular was linked to British economic interests: it was founded by C.H. Walker & Co., which based itself there to extract sand from the dunes for construction work to expand the port of Buenos Aires — its name deriving from the large amount of shells found in the quarries along the coast.[43] A key figure in the economic development of Conchillas was David Evans, a former ship's cook who ran a trading company.[44] Evans, who was known for his personal kindness, was willing to sell all his goods on credit.[44] The former headquarters of his company, Casa Evans, is now a tourist attraction. Today, the evidence of the British founding of Conchillas lies in the architecture of the town, rather than the way of life of its inhabitants.[44]

While not founded by the British, Solís in Maldonado Department was known for its population of British rail workers. Anglo-Uruguayan descendants of these workers still reside in the village.[45]

Montevideo

In 1898, the Central Uruguay Railway constructed houses for its employees in the Peñarol neighbourhood, which was then a village on the outskirts of the capital. This area became the English enclave of 'Neuva Manchester' (New Manchester). The homes for manual workers are characterised by a homogenous terraced design, while the homes built for administrative personnel are more varied and have small front gardens.[46]

The housing complex was declared a National Heritage Site in 1975.[46]

Institutions

There are numerous legacy institutions that serve as reminders of the British presence in Uruguay, including sports clubs, bands, places of worship, and cultural exchange groups. Those below are council institutions of The British Society in Uruguay.[47][lower-alpha 8]

- Anglican Church of Uruguay

- Camara de Comercio Uruguayo-Británica

- Christ Church Montevideo

- City of Montevideo Pipe Band

- Club Uruguayo Británico

- Graduates from British Universities Association of Uruguay

- Instituto Cultural Anglo-Uruguayo

- Montevideo Cricket Club

- Montevideo Players Society

- Old Boys Club & Old Girls Club

- Riverside Pipe Band

- St. Andrew's Society

- Scottish Dance Uruguay

- Silver River Lodge

- Sir Winston Churchill Home & Benevolent Fund

- Sociedad Uruguaya Criadores de Border Collie

- The Allies (Inactive since there are no war ex combatants alive)

- The British Cemetery Montevideo

- The British Hospital

- The British Hospital Guild

- The British Schools Society

- The Connaught Cultural Association

Notable people

- John Adams, architect responsible for Edificio London París (1908) and Palacio Taranco (1910)

- Mateo Aramburu, footballer, forward for FC Schalke 04 II

- Sebastián Coates, footballer, centre back for Uruguay and Sporting CP

- Leonard Crossley, football goalkeeper

- William Huskinson Denstone, editor of The Montevideo Times (1888 – 1925)

- Guillermo Douglas, rower; bronze medallist in single sculls at 1932 Summer Olympics

- Paula Fynn, handball player; bronze medallist at 2015 Pan American Games

- Eduardo Gordon, basketball player, Uruguay squad at 1948 Summer Olympics

- John Harley, footballer for Uruguay and Peñarol

- Thomas Havers, Director of Public Works (1865 – 1870)

- Faustino Harrison, President of the Uruguayan National Council of Government (1962 – 1963)

- Mario Héber Usher, President of the Chamber of Deputies of Uruguay (1966 – 1967)

- Alberto Héber Usher, Chairman of the Uruguayan National Council of Government (1966 – 1967)

- Richard Bannister Hughes, entrepreneur and co-founder of Villa Independencia

- Juan D. Jackson, businessman and philanthropist

- Alfredo Jones Brown, architect

- Samuel Fisher Lafone, entrepreneur

- Beatriz Lockhart, pianist

- Patricia Miller, tennis player; bronze medallist in women's singles at 1987 Pan American Games

- Nina Miranda, singer

- Janine Stanley, field hockey player, represented Uruguay at 2019 Pan American Games

- Duncan Stewart, President of Uruguay (1894)

- Andrew Teuten, footballer; left-back for Montevideo City Torque (2018 – 2021)

Gallery

Monument to Lord Ponsonby at Parque Batlle

Monument to Lord Ponsonby at Parque Batlle Graves at The British Cemetery

Graves at The British Cemetery

Victoria Hall (2013)

Victoria Hall (2013)

See also

Notes

- In general, immigrants to Uruguay from Britain, Germany, France and elsewhere in Northern Europe came largely from middle-class backgrounds, whereas Spanish and Italian migrants were typically from the working-class.[1]

- Before the departure of British forces in September 1807, the commander, Samuel Auchmuty, initiated the first uncensored newspaper in Latin America, The Southern Star.[6]

- Anglo-Argentine author William Henry Hudson chronicled the way of life of British ranchers in his 1885 semi-autobiographical novel, The Purple Land.[11]

- The most successful ranchers of British origin during these years were Daniel Cash, Ricardo Hughes, Alejandro Stirling, Roberto Young, Eduardo Mac Eachen, Juan Mac Coll, Juan Jackson, and Thomas Fair.[13]

- Until this point, beef was preserved only in a dry, salted form. This appealed to a narrow export market — mainly Brazil and Cuba, where it was fed to slaves.[12]

- While The Montevideo Times was the best known English language publication, it ran concurrently with a number of competitors, many of which were short-lived, including The Uruguay News (1891–1898), The Uruguay News Letter (1898–1899), The Uruguay Weekly News (1899–1926), The Herald (1912–1914), The Sunday Morning (1920–1922), and The Sun (1922–1953).[21]

- As a matter of fact, Batllista ideology more often sought to avoid class conflict and encouraged workers to see themselves "not as members of a social class whose interests were necessarily antagonistic to those of employers", but as potential members of the middle-class.[26]

- The Allies is the successor to the Uruguay branch of the Royal British Legion, which closed down because it could not meet the compliance costs of being linked to a UK registered charity.[48]

References

- Weil, Thomas E. (1971). Area Handbook for Uruguay. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 58.

- Harper, Justin (3 May 2012). "British expats flock to cheap and cheerful Uruguay". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- "Brits in South America". BBC News. 6 December 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- Koolhaas, Martín; Mathías Nathan (February 2013). "Inmigrantes Internacionales y Retornados en Uruguay: Magnitud y características: Informe de resultados del Censo de Población 2011" [International Immigrants and Returnees in Uruguay: Magnitude and characteristics: Report results of the Population Census 2011] (PDF) (in Spanish). Uruguay National Institute of Statistics. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- Trujillo, Valentín (13 December 2013). "Historias tras las lápidas". El Observador. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- Krotee, March L. (September 1979). "The Rise and Demise of Sport: A Reflection of Uruguayan Society". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 445: 143. JSTOR 1042962.

- Peter Winn (November 1976). "British Informal Empire in Uruguay in the Nineteenth Century". Past & Present (73): 101. JSTOR 650427.

- Koebel, W. H. (1923). Uruguay. London: T. Fisher Unwin. p. 55. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- Winn, 1976, p. 103

- Will Kaufman; Heidi Slettedahl Macpherson (2005). Britain and the Americas : Culture, Politics, and History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1016–1018. ISBN 9781851094318.

- Weil, 1971, p. 57

- Hudson, Rex A.; Meditz, Sandra W., eds. (1992). Uruguay: a country study (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division. p. 102. ISBN 0-8444-0737-2.

- Ana María Rodríguez (1988). América Latina Entre Dos Imperialismos: la prensa británica de Montevideo frente a la penetración norteamericana (1889-1899) (in Spanish). Montevideo: Universidad de la República. p. 39.

- Cuenca, Alvaro (24 August 2015). "For Fear of 'Turning Native': British Colonialism in Uruguay". Imperial & Global Forum. University of Exeter. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- Burford, Tim (2017). Uruguay. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 315. ISBN 9781784770594.

- Winn, p. 109

- Leonor Berna; Pablo Langone; Silvana Pera (2015). Historia económica y social del Uruguay, 1870–2000. Montevideo: Santillana. p. 498.

- Weil, p. 91

- Gekas, Sakis; Acosta, Camila (6 July 2021). "Greece, Uruguay and the British Informal Empire: From National Narratives to Global History". Historein. doi:10.12681/historein.19500. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- M. H. J. Finch (1981). A Political Economy of Uruguay Since 1870. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 192. ISBN 9781349166237.

- Turcatti, Dante (2013). La Prensa de Inmigracíon en Uruguay (1860–1960). Montevideo: University of the Republic. p. 134. ISBN 978-9974-0-0989-9. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- José Pedro Rilla; Manuel Esmoris (2008). Barrio Peñarol : Patrimonio Industrial Ferroviario (PDF). Montevideo: Intendencia Municipal de Montevideo. pp. 54, 85. ISBN 9789974614420. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- Ernest Satow (2017). Ruxton, Ian (ed.). The Diaries of Sir Ernest Mason Satow, 1889-1895: Uruguay and Morocco. Lulu. p. 2. ISBN 9780359281312.

- Finch, 1981, p. 17

- Finch, p. 12

- Finch, p. 39

- Hudson and Meditz, 1992, p. 22

- Hudson and Meditz, p. 31

- Weil, p. 238

- Burford, 2017, p. 62

- Weil, p. 61

- Turcatti, 2013, pp. 102–103

- "Origins". The British Society in Uruguay. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Empson, Richard (May 2021). Deakin, Geoffrey (ed.). "President's Words" (PDF). Contact. The British Society in Uruguay (128): 1. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Deakin, Geoffrey, ed. (November 2016). "Silver River Lodge" (PDF). Contact. The British Society in Uruguay: 17. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Deakin, Geoffrey, ed. (December 2019). "Silver River Lodge" (PDF). Contact. The British Society in Uruguay: 13. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Stanham, Victoria, ed. (October 2022). "Encuentro Británico-Oriental" (PDF). Contact. The British Society in Uruguay: 37. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- Krotee, 1979, p. 144

- Burford, 2017, p. 39

- "Montevideo Cricket, el club más antiguo del país". LARED21 (in Spanish). 9 June 2003. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- Rodríguez, 1988, p. 39

- Rodríguez, p. 40

- Deakin, Geoffrey, ed. (October 2021). "Into the Provinces with the Anglo" (PDF). Contact. The British Society in Uruguay: 13. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- "History of Conchillas". 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- Burford, 2017, p. 195

- "Ciudad Ferroviaria - Estación, talleres y viviendas de Peñarol". Nómada (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- "BSU Council Institutions". The British Society in Uruguay. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- Biscomb, John (June 2012). Medina, Ricky (ed.). "The Allies News" (PDF). Newsletter. The British Society in Uruguay: 6.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)