Buddhism in Himachal Pradesh

Buddhism in the Himachal Pradesh state of India of has been a long-recorded practice. The spread of Buddhism in the region has occurred intermediately throughout its history. Starting in the 3rd century BCE, Buddhism was propagated by the Maurya Empire under the reign of Ashoka. The region would remain an important center for Buddhism under the Kushan Empire and its vassals.[1] Over the centuries the following of Buddhism has greatly fluctuated. Yet by experiencing revivals and migrations, Buddhism continued to be rooted in the region, particularly in the Lahaul, Spiti and Kinnaur valleys.

Buddhist monasteries (Himachal Pradesh)     .jpg.webp)  Dhankar Monastery *Tabo Monastery and chortens Panorama Nako Monastery, Spiti *Shakyamuni Buddha at the monastery of the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso McLeod Ganj, also called Little Lhasa, capital of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile |

|---|

After the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, escaped from Tibet with his followers in 1959 and took refuge in India, the focus on Tibetan Buddhism spread further and attracted immense international sympathy and support. The Dalai Lama found Dharamshala in Himachal Pradesh as an ideal place to establish his "capital in exile" at McLeod Ganj in close vicinity to Dharamshala, and is called the Little Lhasa and also as Dhasa (a combination of Dharamshala and Lhasa in Tibet). This situation has given the state a unique status in the global firmament of Buddhist traditions. It is now the cradle of Tibetan Buddhism, with its undeniable link to the past activities initiated in the 8th century (in 747 AD) by Guru Padmasambhava (who went to Tibet from Rewalsar in Himachal Pradesh in North India to spread Buddhism), who was known as the "Guru Rinpoche" and the "Second Buddha".[2][3][4][5]

The influence of Buddhism is strong throughout the Trans-Himalayan region or Western Himalayas, formed by the Indian states of Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh and bounded by the Indus River on the extreme west and the Tons-Yamuna River gorge on the east.[6] With the influx of Tibetan refugees into India, in the last over 50 years (since 1959), popularity and practice of Tibetan Buddhism has been notable. Apart from the original practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism in ancient and medieval India, it is now seriously pursued by Tibetans re-settled at Dharamshala (the nodal centre and the 'capital in exile' of the Dalai Lama were initially re-settled) in Himachal Pradesh, Dehradun (Uttarakhand), Kushalnagar (Karnataka), Darjeeling (West Bengal), Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Ladakh.[7][8]

Overview

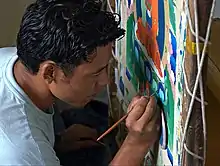

After a lull in the spread of Buddhism in the state during the 10th century, the Tibetan King Yeshe Od of Guge took the initiative to revive it. Of the 21 scholars he had sent to revive Buddhism in the Trans Himalayan region, only two had survived, and one of them was the famous scholar-translator Rinchen Zangpo who transfused Buddhist activity in the state of Himachal Pradesh. Known by the epithet "Lohtsawa" or the "Great Translator", Zangpo built 108 monasteries in the trans-Himalayan region to spread Buddhism, which are considered as the main stay of Vajrayana of Tibetan Buddhism (also known as Lamaism). He institutionalised Buddhism in this region. Zangpo had engaged Kashmiri artists who created wall paintings and sculptures in these legendary 108 monasteries; only a few of these have survived in Himachal Pradesh namely, the Lhalung Monastery, Nako Gompa in Spiti and Tabo Monastery in Spiti, the last named monastery is known as the Ajanta of the Himalayas. In Himachal Pradesh, apart from these ancient Buddhist monasteries set up by Zangpo, his contemporaries of other Buddhist sects built many more monasteries. This activity thus further continued in the subsequent centuries under the four main traditions of Nyingma, Kagyu, Gelug, and Sakya, categorised as per teachings into three "vehicles": Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. These monasteries are mostly in the Spiti, Lahaul and Kinnaur valleys. Some of the well known monasteries are Gandhola Monastery (Drukpa Kargyu sect) Guru Ghantal Monastery, Kardang Monastery (Drukpa sect), Shashur Monastery, Tayul Monastery and Gemur Monastery in the Lahaul Valley, Dhankar Monastery, Kaza Monastery, Kye Monastery, Tangyud Monastery (Sakya sect), Kungri Monastery (of the Nyingma sect), Kardang Monastery (Drukpa Kagyu sect) and Kibber Monastery in the Spiti Valley, and the Bir Monasteries (Bir Tibetan monasteries of the Nyingma, Kagyu and Sakya sects) in the Kangra valley.[5][9]

History

The very earliest influence of Buddhism in Himachal Pradesh is traced to the Ashokan period in the 3rd century BC. He had established many stupas, and one of them was traced to the state in the Kulu valley, as cited in the chronicles of the Chinese travellers.[8] Mention is also made of a much earlier propagation during Buddha's time itself by Sthavira Angira and Stavira Kanakavatsa, in the Kailash area and Kashmir respectively. In the 7th century, King Songtsen Gampo of Tibet had deputed Thomi Sambota to visit Buddhist Viharas in India to imbibe more of Indian Buddhist knowledge. It was in 749 AD that Padmasambhava (hailed as the second Buddha) with his compatriot Shantarakshita established the Vajrayana Buddhism in the Western Himalayan region.[5] Rewalsar lake at Rewalsar in Mandi district is where Padmasambhava (literal meaning "lotus born") is said to have meditated for long years. At Rewalsar, there is also a strange legend of his life linked to the local King, his daughter and the lake. It is one of the most ancient links to Tibetan Buddhism in Himachal Pradesh where Buddhists undertake parikrama of the lake on religious pilgrimage.[8][10][11]

Archaeological evidence in Himachal Pradesh offers strong evidence of Buddhist influence. Numismatic evidence has established the presence of Buddhism in the Kuluta region (upper Beas region of the Kuluta Kingdom) of the state in the 1st century BC and 2nd century AD. On the Palampur-Malan- Dadh-Dharamshala road, 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) from Malan rock inscriptions in Brahmi and Kharoshti scripts of 3rd and 2nd century BC have been discovered on a single granite rock known as Lakhina pathar, which are supported by the Buddhist monuments at Chahri; inscribed pedestals of Vajravarahi (Buddhist tantric goddess) is dated to 5th or early 6th century. Handa's archaeological explorations have also unearthed a headless stone image of Buddha (now in the Kangra Museum) at sites of Chetru and Kanhiara villages; Chetru in local lingua is interpreted as Chaitya in Sanskrit. Names such as Matth and Trilokinath and one dozen maths in Kangra and Mandi districts further point to Buddhist establishments between the 3rd century BC and 6th century AD. Cave type (guha type) Buddhist monastery at Gandhala has been inferred from a copper lot (pot), chased with Jataka episode discovered in a monastic cell in Kullu subdivision of the Kangra division which is dated to the 2nd century AD. Trilokinath and Gandhala (also known as Guru Ghantal), beyond Rohtang la pass are considered classical Buddhist shrines of Indian Buddhism (inferred to predate Padmasmbhava's times by many centuries). Discovery of marble head (7th or 8th century AD) of Avalokiteshvara at the confluence of Chandra and Bhagha Rivers support evidence of monastic activities in these remote regions.[12]

Archaeological evidence also supports the influence of Vajrayana Buddhism influence prior to the 8th century in the region east of Sutlej river. Cult powers of Padmasambhava, before he went to Tibet (before 747 AD), are also deciphered from legends at Nako in Kinnaur, Trilokinath and Gandhala in Lahaul, and Rewalsar in Mandi district. From the mid 8th century (after 747 AD) evidence of Buddhist activities remain obscure till Tibetan Buddhism penetrated the region in the 10th century.[13]

Rinchen Zangpo was urged by Buddhist Guru Shantarakshita from Kashmir, who had already established a monastic order in Tibet, to travel around to spread Buddhism in the trans-Himalayan region. At that time, Zangpo was teaching in Kashmir. He embarked on his campaign to teach Buddhism in the trans-Himalayan region by travelling through Lahaul, Spiti and Kinnaur valleys of the Sutlej River valley, in Himachal Pradesh, then to Ladakh and further on to Tibet, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan. He established Buddhist Dharma in all these regions. This period was called the "Second Coming" of Buddhism in the region since earlier efforts made had not progressed much.[7] It is said that Zangpo's persistence of amalgamating Tibetan Buddhism into the Indian creed was the "Second Advancement" or "Second Coming", also called the "Classical Period". Since then, Tibetan Buddhism has also imbibed many of the religious practices and culture of India. Buddhist monastic art and architecture thus went through a sea change.[5]

Another Buddhist Tantric Guru Deepankara Srijnana (Atisha) (982–1054) was held in high esteem during the period of Zangpo. He had a great influence on Zangpo in teaching the finer aspects of Tantric texts in Sanskrit and the translated texts in Tibetan. Under Atisha's influence there was conceptual reformation of primitive Buddhism in Tibet into the Mahayana Buddhism, which laid stress on "celibacy and morality". This resulted in the evolution of a reformed sect known as Kahdampa, which eventually got subsumed under the Gelukpa sect. This reformation also caused further break-up of Buddhism under several sects and sub sects. The Kings of Guge had a significant role in propagation of the religion, which had strong influence on the architectural planning of Tibetan monasteries. One of the Guge brothers, Chang chub-O, had even got the Tabo Monastery in Spiti refurbished. But Tibet was fragmented under the influence of its various sects and subsects, which attracted Mongol invasion. Three events in the 13th century had profound effect on Tibetan Buddhism; one was Chengiz Khan's invasion of Tibet in 1206; the second event in the second half of thirteenth century was that of the then Chinese ruler Kublai Khan's (of Yuan, who later became a Buddhist); and the third of Kashmir, which until then had been a stronghold of Buddhism, going under Muslim rule after 1339, putting an end to cultural communication with India. Mongol invasion is also credited with uniting Tibet under the institution of the Dalai Lama. While the Mongols favoured the Sakya sect, the Ming dynasty (Chinese) favoured Kargyupa and Kahdampa sects; but these actions resulted in inter-sectoral rivalry and even destruction of each other's monasteries. It was during this period that monasteries were also built on hilltops and many were also well fortified. The period between 1300 AD and 1850 AD marked the development of hill-top monasteries and examples of this type in the western Himalayan region are the Ki Monastery in Spiti and the Hemis Monastery in Ladakh.[14]

Thus, from the 14th century onwards, the monasteries had adopted a fort-like design for its buildings from logistic considerations and built them as "religio-military strongholds"; many of them have disappeared due to invasions but some have survived in Ladakh and Spiti valleys in India. Zangpo's "Classical monasteries" in Western Tibet, in Lahaul, Spiti and Kinnaur in Himachal Pradesh, and in Ladakh have survived and are fairly well preserved for posterity. However, instances of greed and neglect have been reported in some monasteries.[5]

- Tibetan immigration

The Khadamp sect, which was reorganised as "Gelukpa sect" at the start of the 15th century by Tsongkhapa has dominated Tibet and became the "Spiritual and Temporal Authority of Tibet" with the Dalai Lama invested with full authority of this sect. While the founder Lama of Gelukpa sect was Tsongkhapa, his nephew Gendun Drup was the first Grand Lama and since then the mantle has been passed on to the subsequent Lamas under a Reincarnation theory of succession. The fifth Dalai Lama subsumed all of the other sub-sects under his control, with his headquarters at Lhasa as the supreme head of Buddhism in Tibet. The Dalai Lamas also held some political power in certain areas of Tibet until the 14th Dalai Lama emigrated to India in 1959.[15]

The 14th Dalai Lama established his "Government in exile", in 1960 at Mcleod Ganj in the upper part of the town of Dharamshala. This has since become the nerve centre of Tibetan Buddhism with the Tibetan refugees establishing monasteries of their sects, such as the Gelukpa, Sakyapa, Kargyupa, Nyingmapa, Chonangpa and Dragung-Kargyupa; Non-Buddhist of Bön religion also have established their monastery here. Over 40 monasteries (unofficial records) of these sects have been reported.[16]

In order to educate ethnic Tibetan youths in Dharamshala and the Himalayan border students of India, the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies (CIHTS) was established at Varanasi by Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru in consultation with the Dalai Lama. The institute, a Deemed University since 1988, is currently headed by Prof. Ngawang Samten, assisted by faculty members of the institute. Its primary goal is to achieve excellence in the field of Tibetology, Buddhology and Himalayan Studies.[17][18]

Earliest lake and monasteries

The earliest reverential link according to Padmasmabhava's legend is to the Rewalsar lake at Rewalsar in Mandi district of Himachal Pradesh where Padmasambhava is said to have meditated. There are three monasteries located here namely, the ancient Nyingmapa Monastery on periphery of the Rewalsar lake and two new monasteries (of modern construction) namely, the Drigung Kagyu Monastery (a multistoreyed complex behind the ancient monastery) of the Kagyu order and Tso-Pema Ogyen Heru-kai Nyingmapa Gompa.[8][10][19][20]

- Rewalsar

.jpg.webp)

Rewalsar has an ancient divine link for the Buddhists as it is believed that Guru Padmasambhava set out from here on his journey to Tibet to propagate Buddhist dharma. The Rewalsar Lake ('Tso Pema' or 'Pad-ma-can' to Tibetans) has a legend that started the belief that on the islands of floating reeds of the lake the spirit of Padmasambhava's resides. According to folk legend, Padmasmabhava tried to teach Buddhist dharma to the daughter (Mandarava) of the King of Mandi, Arshadhara of Sahor, which was seriously resented by the King. It is also mentioned that Mandarva was enamoured of Padmasambhava of Nalanda. The King, therefore, ordered Padmasambhava to be burnt alive. However, the pyre burned for a full week, with great clouds of black smoke arising from it and a lake appeared there after a week at the spot where he was supposed to have been burnt. Then, Padmasambhava (also known as Vajracharya), unscathed by the fire, is said to have appeared seated on a full-blown lotus from within a lotus in the middle of the lake. One version states that the King, as a repentance for his wrong actions, married his daughter with Padmasambhava. Another version states that Mandarava (stated to be the sister of Shantarakshita) as repentance, left her parents' house, and meditated near a well, which has now become a shrine (worshipped by Tibetan Buddhists as a manifestation of Shakthi). It was from this lake that Padmasambhava travelled to Tibet to spread the Vajrayana Buddhism.[8][11][21] Rawalsar has two monasteries, namely, the Drikung Kagyu Gompa and Tso-Pema Ogyen Heru-kai Nyingmapa Gompa.[10][20][22]

To commemorate Padmasmabahava (so named after he emerged from the Padmacan lake or lotus lake), a monastery was built on the western shore of the lake, called the Nyingmapa Monastery (built in Central Tibetan fashion), which has been expanded manifold into a multistoreyed pagoda type structure, with several renovations done till the late 19th century. A large gilded statue of Padmasambahava in the formal attire as the manifestation of Guru Rinpoche is deified here. There are two other new monasteries built around the ancient monastery; these are the Drigung Kagyu Monastery of the Kagyupa order and the other monastery called the Tso-Pema Ogyen Heru-kai Nyingmapa Gompa of the Nyingma sect; though of modern construction these two have retained the aesthetic Tibetan architectural ambience.[21]

In 2004, to commemorate the birthday of Padmasambhava, the Tsechu fair was held here, after a gap of 12 years. The fair was inaugurated by the Dalai Lama and was attended by Urgyen Trinley Dorje Karmapa along with 50,000 other Buddhist pilgrims. The Dalai Lama also performed a parikrama (circumambulation) of the lake.[23]

Rinchen Zangpo's monasteries

Rinchen Zangpo, the famous scholar-translator, established 108 monasteries during his mission undertaken in the 10th century to propagate Buddhist Dharma in the Trans-Himalayan region. A few of them, which have survived in Himachal Pradesh, present exquisite monasteries of artistic and architectural excellence in Lahaul, Spiti and Kinnaur valleys of the Sutlej River valley, such as the Tabo monastery, Lhalung monastery and Nako monastery.

Tabo monastery

Tabo Monastery (or Tabo Chos-Khor Monastery) was founded in 996 AD (and refurbished in 1042 AD) by Rinchen Zangpo; it is considered the oldest monastery in Himachal Pradesh. It located at the southern edge of the Trans Himalayan plateau in the Spiti Valley on the banks of the Spiti River, in the very arid, cold and rocky area at an altitude of 3,050 metres (10,010 ft). The sprawling monastery, spread over an area of 6,300 square metres (68,000 sq ft), has nine temples – the Temple of the Enlightened Gods (gTug-Lha-khang), the Golden Temple (gSer-khang), the Initiation Temple (dKyil-kHor- khang), the Bodhisattva Maitreya Temple (Byams-Pa Chen-po Lha-khang), the Temple of Dromton (Brom-ston Lha khang), the Chamber of Picture Treasures (Z'al-ma), the Large Temple of Dromton (Brom-ston Lha khang), the Mahakala Vajra Bhairava Temple (Gon-khang) and the White Temple (dKar-abyum Lha-Khang) (out of these nine, the first four are considered the oldest temples while the others were later additions) – 23 chortens, monks' residences and an extension that houses the nuns' residence. It was initially an important centre of learning of the Kadampa order, which later developed into the Gelukpa order. It was severely damaged in the 1975 Kinnaur earthquake and has since been re-built with a new Dukhang (assembly hall). The Dalai Lama held the Kalachakra ceremonies here in 1983 and 1996. The year 1996 marked 1000 years of Tabo Monastery's existence. A number of caves carved into the cliff face are located above the monastery, which are used by monks for meditation. The monastery is studded with large collection of precious Thangka (scroll paintings), manuscripts, well-preserved statues, frescos and extensive murals that cover almost every wall. The monastery is a national historic treasure of India and preserved by the Archaeological Survey of India.[3]

The few original paintings of Bodhisattvas, from the period of the renovation of Tabo monastery in 1042, seen in the Dukong (assembly hall), are similar in style to those seen at Alchi Monastery in its aesthetic elegance. These have a gentle form with stress on unique detailing of textiles and ornaments. The paintings in the assembly hall are dedicated to Vairochana. Also seen are paintings of two narrative sequences namely, the first narrative is about the visit by Sudhana, a merchant's son, deputed by Bodhisattva Manjushri, on a spiritual mission, while the second narrative depicts the life of the Buddha. The Dalai Lama has expressed his desire to retire to Tabo, since he maintains that the Tabo Monastery is one of the holiest.[3]

It is a World Heritage Site listed by UNESCO. Its sanctity in the Trans Himalayan Buddhism is considered as second only to that of the Tholing Monastery in Tibet.[24]

Lhalung monastery

Lhalung Monastery, Lhalun Monastery or Lalung Monastery (also known as the Sarkhang or Golden Temple), one of the earliest monasteries (considered second to Tabo monastery in importance) founded in Spiti valley, near the Lingti river. It is dated to the late 10th century and credited to Rinchen Zangpo. Village of Lhalung ( meaning: 'land of the gods') in the vicinity of the monastery, at an altitude of 3,658 metres (12,001 ft), has 45 homes. A few chortens are located on the way to the monastery. It is said that the Lhalung Devta is head of all the Devtas of the valley and emerges from the Tangmar mountain beyond the village. It was a complex of nine shrines enclosed within a dilapidated wall with the main chapel richly decorated. The monastery is inferred as an ancient centre of learning and debate (local name: Choshore) on the basis of old ruins of several temples seen around the five buildings of the monastery, apart from an equally ancient sacred tree. Serkhang, the golden hall of the temple complex has is studded with images (most of them gilded) of deities (51 deities) – mounted on walls or erected on a central altar.[25][26][27][28][29][30]

Nako monastery

The Nako monastery is located (3,660 metres (12,010 ft)) near the India-China border in the trans-Himalayan region in Nako village in Kinnaur district at its western edge. The monastery complex in the village has four temples in an enclosure built with mud walls. It is also dated to the second coming of Buddhism to the region and is credited to Rinchen Zangpo. The area is known for the Nako Lake, which forms part of the border of the village.[3][31]

Though the monastery complex looks simple from outside, in the interiors of the complex, the wall paintings in the monastery are delicately executed. Influence of the Ajanta style of painting, is distinct "in the tonal variation of body hues to produce an effect of light and shade". The elegant divine figures have placid expressions, a reflection of the finest classical art of India.[3][31]

The four temples are well preserved; the main temple and the upper temple considered the oldest of the four structures have the original clay sculptures, murals and ceiling panels – larger temple of these two is known as the 'Translator's Temple'; the third structure is a small white temple, partly dilapidated, has a wooden door frame depicting scenes of the Life of the Buddha carved on the lintel; and the fourth structure is of the same size as the Upper Temple and is also situated next to it, which is known as "rGya-dpag-pa'i lHa-khang" meaning temple of wide proportions.[31]

An impression of a foot found near the Nako Lake is ascribed to Guru Padmasambhava.[32] In a nearby village called Tashigang, several caves are found where it is said Guru Padmasambhava meditated and gave discourse to his disciples. An image is stated to grow hair.[24]

Fourteenth century and later monasteries

The trend of building fortified Buddhist monasteries was started from the 14th century onwards. However, very few have survived. Of these, Tangyud monastery, Dhankar monastery and Key monastery in Spiti valley are some of the well known ones.

Tangyud Monastery

The Tangyud Monastery in the Spiti valley was built in the early 14th century when the Sakyapas rose to power under Mongol patronage. It is built like a fortified castle on the edge of a deep canyon, with massive slanted mud walls and battlements with vertical red ochre and white vertical stripes which make them look much taller than they really are. It is at an altitude of 4,587 metres (15,049 ft), on the edge of a deep canyon and overlooking the town of Kaza, 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) from the town. It is one of only two monasteries belonging to the Sakya sect left in Spiti – the other, at Kaza itself, is small and relatively insignificant. It is thought, however, that there was an earlier Kadampa establishment here founded by Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055 AD) and named Rador-lha. The name, Tangyud, may refer to the Sakya revision of the Tang-rGyud, or the 87 volumes of Tantra treatises which form part of the Tengyur; this was done around 1310 AD by a team of scholars under the Sakya lama, Ch'os-Kyi-O'd-zer. The unplanned arrangement of the monastery is attributed to several modifications carried out after it was ransacked by invasions of Central Tibet by Mongols, in 1655 AD. The monastery is also famous for the expertise of the Sakyapa tantric cult that even dacoits are scared to rob this monastery.[33][34]

Dhankar Monastery

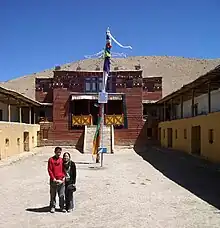

Dhankar Monastery also spelt Drangkhar or Dhangkar Gompa; Brang-mkhar or Grang-mkhar, situated in the Spiti Valley between the towns of Kaza and Tabo at an elevation of 3,894 metres (12,776 ft) is a fort monastery similar to the Key Monastery and Tangyud Monastery in Spiti built in the Central Tibetan pattern.[35] Dhankar was the traditional capital of the Spiti Valley Kingdom during the 17th century. The complex is built on a 300 metres (980 ft) high spur overlooking the confluence of the Spiti River and Pin River – one of the world's most spectacular settings for a gompa. Dhang or dang means cliff, and kar or khar means fort. Hence, Dhangkar means fort on a cliff. It belongs to the Gelukpa order but claims to its earlier founding in the 12th century has put forth by the local monks. Below this Gompa is the small village of Shichilling where the new Dhankar Monastery has been built. It is home to about 150 monks belonging to the Gelukpa sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Dhankar is approachable by a road, good for small vehicles only, that branches off for Dhankar from the main Kaza-Samdu road at a point around 24 kilometres (15 mi) from Kaza.[36][37]

In 2006, World Monuments Fund selected Dhankar gompa as one of the 100 most endangered sites in the world.[38] A non-profit group, Dhangkar Initiative, is attempting to organize its conservation.[39]

Key Monastery

The earliest history of Key Monastery is traced to Dromtön (Brom-ston, 1008–1064 CE), a pupil of the famous teacher, Atisha, in the 11th century. This however, refers to destroyed Kadampa monastery at the nearby village of Rangrik, which was probably destroyed in the 14th century when the Sakya sect rose to power with Mongol assistance. In the wake of the Chinese influence, it was rebuilt during the 14th century as an outstanding example of the monastic architecture.[40][41]

In the 17th century, during the reign of the Fifth Dalai Lama, Key was attacked again by the Mongols and later became a Gelugpa establishment. In 1820, it was sacked again during the wars between Ladakh and Kullu. In 1841, it was severely damaged by the Dogra army under Ghulam Khan and Rahim Khan. Later that same year it suffered more damage from a Sikh army. In the 1840s, it was also ravaged by fire and in 1975 a violent earthquake caused more damage, which was repaired with the help of the Archaeological Survey of India and the State Public Works Department. The successive trails of destruction and patch-up jobs have resulted in a haphazard growth of box-like structures, and so the monastery looks like a fort, where temples are built on top of one another. The walls of the monastery are covered by paintings and murals. It is an outstanding example of the monastic architecture, which developed during the 14th century in the wake of the Chinese influence.[42]

Key monastery has a collection of ancient murals and books of high aesthetic value and it enshrines Buddha images and idols, in the position of Dhyana.[43]

Monasteries in Dharamshala

Subsequent to the 14th Dalai Lama establishing his Tibetan exile government at Mcleod Ganj (a former colonial British summer picnic spot) near upper Dharamshala, the ancient Namgyal Monastery, which was first established by the third Dalai Lama in 1579 in Tibet, was relocated to Dharamshala (the district headquarters of the Kangra district), in 1959. It is now the personal monastery of the Dalai Lama. Two hundred monks and young trainee monks reside here. They pursue studies of the major texts of Buddhist Sutras and Tantras, as also the Tibetan and English Languages.[44]

Tsuglagkhang

An important Buddhist shrine (located opposite to the Namgyal Monastery in the same courtyard) in the town is the Tsuglagkhang or Tsuglag Khang, known as the Dalai Lama's temple. It houses the statues, in sitting postures, of Shakyamuni (gilded)- the central image, Avalokiteśvara (the deity of compassion sculpted in silver with eleven faces and thousand arms and eyes -linked to a legend), and Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) – both facing the direction of Tibet – and also the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts. Dalai Lama's residence is opposite to this temple. A festival is held here every year, during April and May, when traditional dances and plays are enacted.[45][46][47]8 kilometres (5.0 mi) away from Dharamshala, at Sidhpur, a small monastery called the Gompa Dip Tse-Chok Ling, the Gangchen Kyishong (called Gangkyi in short by Tibetans and Library by Indians is the premises of the Tibetan government-in-exile), Mani Lakhang Stupa, Nechung Monastery, Norbulingka Institute, Sidhpur are located. The Karmapa (who was in Norbulinga in Tibet before taking refuge in India) is now living in Gyato monastery.

Kalachakra Temple

Kalachakra Temple is located adjoining the Tsulagkhang which is dedicated to the Kalachakra. The temple has fresco decorations of 722 deities of the mandala, Shakayamuni Buddha, and the central Kalachakra image. Dalai Lama personally directed the painting of the frescos done by three master painters over a period of three years. The walls and columns here have many traditional Tibetan Thangka paintings.[45]

Library of Tibetan works and archives

A Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA) was also set up by the Dalai Lama, in June 1970, to provide exhaustive information on Buddhist and Tibetan culture. The LTWA boasts of more than 110,000 titles in the form of manuscripts (40% are the Tibetan originals[46]), books and documents; hundreds of thangkas (Tibetan scroll paintings), statues and other artefacts; and over 6,000 photographs, and many other materials. The LTWA has nine departments guided by a governing body. The library conducts seminars, talks, meetings and discussions and also brings out an annual 'News Letter.' On the third floor of this library there is a museum (opened in 1974) that houses notable artefacts such as a three-dimensional carved wooden mandala of Avalokiteshvara and items that date back to the 12th century.[48]

Norbulingka Institute

The Norbulingka Institute founded in 1988, by the present Dalai Lama has the primary objective of preserving the Tibetan language and cultural heritage. This institute has been patterned on the same lines as Norbulingka, the traditional summer residence of the Dalai Lamas, in Lhasa, amidst a well-maintained garden setting, and the emphasis here is more on traditional art. A temple named as the "Seat of Happiness Temple" (Deden Tsuglakhang) is located here. Around this temple, craft centres are located, which specialise in traditional forms of Thanka painting to Metal art that are considered integral to Tibetan Monastery architecture. 300 artisans work here and also impart training to their wards.[49]

The Losel Doll Museum here has diorama displays of traditional Tibetan scenes, using miniature Tibetan dolls in traditional costumes.

A short distance from the institute lies the Dolma Ling Buddhist nunnery[50] and the Gyato Monastery, temporary residence of the 17th Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje.

Festivals

Buddhist festivals held in Himachal Pradesh are predominantly connected with their religious identity. They relate to the seasons (New Year as per Lunar and Solar calendars), Buddha's birth and death anniversaries, and also the sacred days such as the birthdays of the Bodhistavas. The annual calendar is filled with festivals and some the popular ones starting with January are the following.[51][52]

In January, in the Lahaul region, a carnival called the Halda Festival is held when people carry twigs of cedar tree to a location specified by the lamas and then throw it into a bonfire accompanied by various dances.[53]

During February/March, the Tibetan New Year is observed as Losar festival by all Tibetan Buddhists in the state with processions, music and dancing; mask dances or chaam dances are popular on this occasion. The Dalai Lama holds teaching discourses at Dharmashala during this festival.[54]

Ki Cham festival held in June/July is specific to Ki monastery. On this occasion, whirling mask dances are held in the monastery, which is watched by people from many villages of Spiti.[54]

An ancient practice of a trade fair called the La Darcha is held in August in Spiti. Buddhist dances and Buddhist sports are popular and held along with rural marketing fair. Its social, economic and cultural significance relates to ancient ties with Tibet. Instead of La Darch ground near the Chicham village, the festival is now held at Kaza, headquarters of Spiti subdivision.[54][55]

In November, the Guktor festival is held in Dhankar monastery in Spiti when processions and mask dances are the set festive practices.[54]

In December, the International Himalayan Festival (a three-day event) is held in Mcleod Ganj, the exile capital of Tibet to celebrate the Dalai Lama getting the Nobel Peace Prize. Dance and music mark the day with resolve to promote peace and cultural amity. On this occasion, the Dalai Lama blesses Mcleod Ganj.[54]

Notes

- Ahluwalia, Manjit Singh (1998). Social, Cultural, and Economic History of Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing. ISBN 9788173870897.

- "His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyaltso". Namgyal Monastery. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Benoy K. Behl. "Trans-Himalayan Murals". The Front Line: The Hindu Group. Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "About Tabo Monastery". Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Handa, O.C (2004). Buddhist Monasteries of Himachal. pp. 11–16. ISBN 81-7387-170-1. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Handa p.21

- "Tibetan Buddhism". Culturopedia. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- "Buddhism in Himachal Pradesh". Buddhist Tourism. Archived from the original on 2 August 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- "Tourism:Monasteries". Government of Himachal Pradesh. Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- "Beas Circuit, Mandi:Rewalsar". National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- "One version of the Buddhist legend". Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- Handa p.75-80

- Handa p.86

- Handa pp.94–97

- Handa pp.97–99

- Handa pp.218–219

- "India education". Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- "Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies". Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Handa p.221

- "Buddhist monasteries in Rawalsar". Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- Handa pp.214–216

- "Devotees throng Rewalsar". Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- "Dalai Lama performs parikrama at Rewalsar". The Tribune. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- "Lahaul Spiti". Government of Himachal Pradesh. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- "Tourism in Lahaul Spiti". National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Kapadia p. 82

- "Homestays of Spiti- The Forbidden Land". Day 4: Demul to Lhalung. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- "Luxury Tours in Indian Himalayas". Tabo-Lhalung-Dhankar-Schiling. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Kapadia p. 64

- Rizvi pp. 59, 256

- "Nako Monastery". Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- "About Himachal". Tourism Department. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Handa p.139-140

- Kapadia p. 204

- Handa pp. 131, 149

- Francke p. 43

- "The Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries of the Spiti Valley".

- "World Monuments Watch 1996–2006". World Monuments Fund. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- "The Dhangkar Initiative".

- Francke pp. 45–47

- Handa pp. 97, 99

- Handa pp. 100–101

- SurfIndia.com – Kye monastery Archived 4 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Namgyal Monastery as it exists today in India". Namgyal Monastery. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- "Dalai Lama Temple Complex". Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Deshpande, Aruna (2005). India: A Divine Destination. p. 476. ISBN 81-242-0556-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA)". Planning Commission NGO Database. Planning Commission, Government of India. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- "History of the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives". History of the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Bernstorff, Dagmar; Hubertus von Welck (2003). Exile as challenge: the Tibetan diaspora. p. 305. ISBN 81-250-2555-3. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Bindloss, Joe; Singh, Sarina; Bainbridge, James; Brown, Lindsay; Elliott, Mark; Butler, Stuart (2007). India. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

Norbulingka Institute.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Bindloss, Joe; Singh, Sarina (2007). India. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

Buddhist Festivals in Himachal Pradesh.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Buddhist Festivals and Holidays". Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- "Buddhist festivals in Himachal Pradesh". Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- Bindloss p.283

- Ahluwalia, Manjit Singh (1998). Social, cultural, and economic history of Himachal Pradesh. p. 92. ISBN 81-7387-089-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

References

- Kapadia, Harish. (1999). Spiti: Adventures in the Trans-Himalaya. Second Edition. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi. ISBN 81-7387-093-4

- Handa, O. C. (1987). Buddhist Monasteries in Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85182-03-5.

- Janet Rizvi. (1996). Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Delhi. ISBN 0-19-564546-4.

- Deshpande, Aruna (2005). India: A Divine Destination. Crest Publishing House. ISBN 81-242-0556-6.

- Francke, A. H. (1914). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Vol. I, Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.