Bulgaria and the euro

Bulgaria plans to adopt the euro and become the 21st member state of the eurozone. The Bulgarian lev has been on the currency board since 1997 through a fixed exchange rate of the lev against the Deutsche Mark and the euro. Bulgaria's target date for introduction of the euro is 1 January 2025, which would make the euro only the second national currency of the country since the lev was introduced over 140 years ago. The official exchange rate is 1.95583 lev for 1 euro.

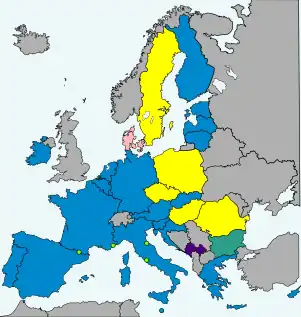

- European Union member states

-

5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member states

Convergence criteria

When it joined the European Union in 2007, Bulgaria committed to switching its currency, the lev, to the euro, as stated in the 2005 EU accession treaty. The transition will occur once the country meets all the euro convergence criteria; it currently meets three of the five. As the lev was fixed to the Deutsche Mark at par, the lev's peg effectively switched to the euro on 1 January 1999, at the rate of 1.95583 leva = 1 euro, which was the Deutsche Mark's fixed exchange rate to the euro.[1]

Bulgarian euro coins have not yet been designed, but the Madara Rider has already been selected as the motif on the obverse ("national" side) of the coins. Bulgaria officially joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) on 10 July 2020.[2][3] Bulgarian government and central bank officials adopted a draft national plan for euro adoption on 30 June 2021,[4] after stating that same day Bulgaria's intention to adopt the euro on 1 January 2024.[5] In May 2022, the government adopted a more definitive version of its euro introduction plan, reaffirming the country's commitment to adopt the euro on the target date.[6] On 21 February 2023, Bulgaria scrapped the idea of adopting the single currency on 1 January 2024 due to internal political crisis.[7]

The Maastricht Treaty, which Bulgaria acceded to by way of its EU accession treaty, requires that all European Union member states join the euro once certain economic criteria are met.

In November 2007, Bulgarian Finance Minister Plamen Oresharski had stated that his goal was to comply with all five convergence criteria by 2009 and adopt the euro in 2012.[8] But Bulgaria did not comply with the requirement to be an ERM II member for at least two years, nor did it satisfy the price stability criterion in 2008. Bulgaria's inflation in the 12 months from April 2007 to March 2008 reached 9.4%, well above the reference value limit of 3.2%.

However, Bulgaria fulfilled the state budget criterion of only having a maximum deficit of 3% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). The country had posted surpluses since 2003, which in 2007 represented 3.4% of its GDP (at the time, the EC forecast that it would remain at 3.2% of GDP in both 2008 and 2009). Bulgaria also complied with the public debt criteria. During the prior decade, the Bulgarian debt had declined from 50% of GDP to 18% in 2007, and was expected to reach 11% in 2009.[9] Finally, the average for the long-term interest rate during the prior year was 4.7% in March 2008, well within the reference limit of 6.5%.[10]

A 2008 analysis said that Bulgaria would not be able to join the eurozone earlier than 2015 due to the high inflation and the repercussions of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis.[11] Some members of Bulgarian government, notably economy minister Petar Dimitrov, speculated about unilaterally introducing the euro, which was not well-met by the European Commission.[12]

Bulgaria met three out of the five criteria in the last convergence report published by the European Central Bank in June 2022.

Joining ERM II

The Bulgarian lev has been pegged to the euro since the latter was launched in 1999, at a fixed rate of €1 = BGN 1.95583, through a strictly managed currency board. Prior to that, the lev was pegged on par to the German Mark. While the currency board which pegs Bulgaria to the euro has been seen as beneficial to the country fulfilling criteria so quickly,[13] the ECB has pressured Bulgaria to drop it as it did not know how to let a country using a currency board join the euro. The Bulgarian Prime Minister has stated the desire to keep the currency board until the euro was adopted. However, factors such as a high inflation, an unrealistic exchange rate with the euro and the country's low productivity are negatively affected by the system.[14]

Simeon Dyankov, Bulgaria's then-finance minister, said in September 2009 that Bulgaria planned to enter ERM II in November,[15][16][17] but this was delayed. It was then delayed further due to an increased budget deficit, outside the Maastricht criteria.[18][19] Since 2011, Bulgaria's non-membership of the ERM has been the primary factor that prevented euro membership, as Bulgaria met the other criteria for euro adoption. In July 2011, Dyankov stated that the government would not adopt the euro as long as the European sovereign-debt crisis was ongoing.[20][21][22] In 2011, Bulgaria's Minister of Finance Simeon Djankov stated that adoption of the euro would be postponed until the end of the eurozone crisis.[20]

In January 2015, then-Finance Minister Vladislav Goranov (under Prime Minister Boyko Borisov) changed approaches and said that it was possible for Bulgaria to join ERM II before the government's term ended. Goranov said he would begin talks with the Eurogroup[23] and a co-ordination council to prepare the country for eurozone membership. The council was to draft a plan for the introduction of the euro, propose a target date, and organise the preparation and coordination of the expert working groups.[24]

This approach was supported by former Bulgarian National Bank governor Kolyo Paramov, who had been in office when the state currency board was established. Paramov argued that adoption would "trigger a number of positive economic effects":

- Sufficient money supply (leading to increased lending, which is needed to improve economic growth)[25]

- Getting rid of the currency board that prevents the national bank from functioning as a lender of last resort to rescue banks in financial trouble[25]

- Private and public lending benefiting from lower interest rates (at least half as high)[25]

Former Bulgarian National Bank deputy governor Emil Harsev agreed with Paramov, stating that it was possible to adopt the euro in 2018 and that "Bulgaria's membership in the eurozone will bring only positive effect on the economy" because "since [the establishment of] the currency board in 1997, we have been accepting all the negative effects of accession into the eurozone without getting the positive ones (access to the European financial market)".[26]

Following the reelection of Borisov's government in 2017, he declared his intention apply to join ERM II,[27] but Goranov elaborated that the government would only seek to join once the eurozone states were ready to approve the application, and that he expected to have clarity on the matter by the end of 2017.[28] On taking the presidency of the EU Council in January 2018, Borisov indicated no clarification had been given but announced he was going to pursue applications for both ERM II and Schengen by July 2018 regardless.[29][30][31][32] Bulgaria sent a letter to the Eurogroup in July 2018 expressing its desire to join ERM II and committing to enter into a "close cooperation" agreement with the EU banking union.[33][34]

In January 2019, Goranov said he hoped that Bulgaria could join the ERM II mechanism in July and introduce the euro on 1 January 2022.[35] However, the first deadline was pushed back to July 2019 due to extra conditions requested by eurozone governments, namely that Bulgaria:[36]

- Join the banking union at the same time as ERM (meaning Bulgaria's banks must first pass stress-tests)

- Reinforce supervision of the non-bank financial sector and fully implement EU anti money-laundering rules

- Thoroughly implement the reforms of the Mechanism for Cooperation and Verification (CVM)

While the CVM reforms are mentioned, and progress in judicial reform and organised crime is expected, leaving the CVM is not a precondition.[36]

As of October 2019, Goranov's target was to enter the ERM II by April 2020.[37] In January 2020, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said that it was possible for Bulgaria to join ERM II later in 2020 and adopt the euro in 2023.[38] Borisov stated in February 2020 that Bulgaria's application would be reviewed in July.[39] In March, the Bulgarian central bank said that this target was no longer realistic due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[40] However, in April Borisov stated that he would push forward the application by the end of April.[41] The reason he gave for this U-turn was the 500 billion euros rescue package to deal with the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, which the finance ministers of the Eurogroup had agreed upon on 10 April.[42] On 24 April, Fitch Ratings announced that they would probably upgrade Bulgaria's foreign currency issuer default ratings (IDR) between Bulgaria's accession to ERM II and euro adoption:

"… Given that the COVID-19 pandemic response is taking up significant resources with regard to political engagement at the EU-wide level, facilitating the Bulgarian lev's ERM2 accession may decline as a relative priority for European institutions. If concerns about risks ease and the process resumes, this would be supportive of the rating, as underlined by our view that all things being equal, we would upgrade Bulgaria's Long-Term Foreign-Currency IDR by two notches between admission to the ERM II and joining the euro."[43]

On 30 April 2020, Bulgaria officially submitted documents to the European Central Bank to apply to join ERM II, the first step to introducing the euro.[44] On 12 May, European Commission Executive Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis stated that Bulgaria could join ERM II together with Croatia in July,[45] which both countries did on 10 July.[2]

Joining the eurozone

Bulgaria is in the process of joining the eurozone. On 17 February 2023, Finance Minister Rositsa Velkova announced that Bulgaria will not join the eurozone on 1 January 2024 and that the new target date for the entry into the euro area is 1 January 2025.[46] In April 2023, however, enough signatures were collected to put the entry to a referendum.[47] In June 2023 the referendum has been rejected by Bulgaria's parliament with 98 votes against, 46 abstensions and 68 votes in favour.[48][49] On 26 July 2023, the newly formed Bulgarian government adopted a programme which stated that the switch to the euro in January 2025 is one of the main government priorities. [50]

Status

| Assessment month | Country | HICP inflation rate[51][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[52] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[53][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget deficit to GDP[54] | Debt-to-GDP ratio[55] | ERM II member[56] | Change in rate[57][58][nb 3] | |||||

| 2012 ECB Report[nb 4] | Reference values | Max. 3.1%[nb 5] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

None open (as of 31 March 2012) | Min. 2 years (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2011) |

Max. 5.80%[nb 7] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Yes[59][60] (as of 31 Mar 2012) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2011)[61] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2011)[61] | |||||||

| 2.7% | Open (Closed in June 2012) | No | 0.0% | 5.30% | No | |||

| 2.1% | 16.3% | |||||||

| 2013 ECB Report[nb 8] | Reference values | Max. 2.7%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2013) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2012) |

Max. 5.5%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Yes[62][63] (as of 30 Apr 2013) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2012)[64] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2012)[64] | |||||||

| 2.4% | None | No | 0.0% | 3.89% | Unknown | |||

| 0.8% | 18.5% | |||||||

| 2014 ECB Report[nb 10] | Reference values | Max. 1.7%[nb 11] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2014) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2013) |

Max. 6.2%[nb 12] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Yes[65][66] (as of 30 Apr 2014) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2013)[67] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2013)[67] | |||||||

| -0.8% | None | No | 0.0% | 3.52% | No | |||

| 1.5% | 18.9% | |||||||

| 2016 ECB Report[nb 13] | Reference values | Max. 0.7%[nb 14] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

None open (as of 18 May 2016) | Min. 2 years (as of 18 May 2016) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2015) |

Max. 4.0%[nb 15] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

Yes[68][69] (as of 18 May 2016) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2015)[70] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2015)[70] | |||||||

| -1.0% | None | No | 0.0% | 2.5% | No | |||

| 2.1% | 26.7% | |||||||

| 2018 ECB Report[nb 16] | Reference values | Max. 1.9%[nb 17] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

None open (as of 3 May 2018) | Min. 2 years (as of 3 May 2018) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2017) |

Max. 3.2%[nb 18] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

Yes[71][72] (as of 20 March 2018) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2017)[73] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2017)[73] | |||||||

| 1.4% | None | No | 0.0% | 1.4% | No | |||

| -0.9% (surplus) | 25.4% | |||||||

| 2020 ECB Report[nb 19] | Reference values | Max. 1.8%[nb 20] (as of 31 Mar 2020) |

None open (as of 7 May 2020) | Min. 2 years (as of 7 May 2020) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2019) |

Max. 2.9%[nb 21] (as of 31 Mar 2020) |

Yes[74][75] (as of 24 March 2020) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2019)[76] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2019)[76] | |||||||

| 2.6% | None | No | 0.0% | 0.3% | No | |||

| -2.1% (surplus) | 20.4% | |||||||

| 2022 ECB Report[nb 22] | Reference values | Max. 4.9%[nb 23] (as of April 2022) |

None open (as of 25 May 2022) | Min. 2 years (as of 25 May 2022) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2021) |

Max. 2.6%[nb 23] (as of April 2022) |

Yes[77][78] (as of 25 March 2022) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2021)[77] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2021)[77] | |||||||

| 5.9% | None | 1 year, 10 months | 0.0% | 0.5% | No | |||

| 4.1% (exempt) | 25.1% | |||||||

- Notes

- The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2012.[59]

- Sweden, Ireland and Slovenia were the reference states.[59]

- The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

- Sweden and Slovenia were the reference states, with Ireland excluded as an outlier.[59]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2013.[62]

- Sweden, Latvia and Ireland were the reference states.[62]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2014.[65]

- Latvia, Portugal and Ireland were the reference states, with Greece, Bulgaria and Cyprus excluded as outliers.[65]

- Latvia, Ireland and Portugal were the reference states.[65]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2016.[68]

- Bulgaria, Slovenia and Spain were the reference states, with Cyprus and Romania excluded as outliers.[68]

- Slovenia, Spain and Bulgaria were the reference states.[68]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2018.[71]

- Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[71]

- Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[71]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2020.[74]

- Portugal, Cyprus, and Italy were the reference states.[74]

- Portugal, Cyprus, and Italy were the reference states.[74]

- Reference values from the Convergence Report of June 2022.[77]

- France, Finland, and Greece were the reference states.[77]

Advantages of euro adoption

Because the lev is pegged to the euro at a fixed exchange rate, it can be argued that Bulgaria is already a de facto member of the euro area insofar as it cannot pursue an independent monetary policy and is bound by the monetary policy and interest rate decisions of the European Central Bank, without having a say. Adopting the euro and thereby becoming a de jure member of the euro area would enhance Bulgaria's position by giving it a voice in the ECB.[42]

Moreover, the fact that the lev is pegged to the euro at a fixed exchange rate also means that Bulgaria cannot devalue its currency in order to make its exports more competitive. Therefore, Bulgaria would not lose anything in this regard by adopting the euro.[42]

Other advantages of adopting the euro include the improved supervision of Bulgaria's systemically important banks once it has joined ERM II together with the European banking union, and the decreased cost of borrowing and full access to the eurozone's COVID-19 pandemic rescue packages.[42]

Selecting the design

Bulgarian euro coins will replace the lev once the convergence criteria are fulfilled. On the occasion of the signing of the EU accession treaty on 25 April 2005, the Bulgarian National Bank issued a commemorative coin with a face value of 1.95583 leva, giving it a nominal value of exactly 1 euro.[82][83]

The Madara Rider was one of the favourites to become the symbol of Bulgaria to be used on the "national" (obverse) side of the country's euro coins. Other eminent contenders to be the 'symbol of Bulgaria' were ancient traditional nestinars (Bulgarian fire dancers), Cyrillic script,[84] the Rila Monastery[85] and the Tsarevets medieval fortress near Veliko Turnovo.[85]

On 17 June 2008, debates on the design of future Bulgarian euro coins were held all over the country, continuing until 29 June when a vote was held on the symbol to be used on all coins. Bulgarians voted in post offices, gas stations and schools.[86][87] That same day, the winner was announced: a plurality of voters, 25.44%, had chosen the Madara Rider to be depicted on future euro coins.[88][89][90][91]

On July 24, 2023,[92] in an interview before the BTA, the governor of the BNB - Dimitar Radev announced that at a meeting of the BNB Governing Council it was decided that the Bulgarian national side of the euro coins would be identical to that of the lev coins, namely:

- on the coins of 1 euro cent, 2 euro cents, 5 euro cents, 10 euro cents, 20 euro cents and 50 euro cents, the Madar horseman should be depicted, as well as the Cyrillic inscription "Stotinka" (the Bulgarian denomination of the Bulgarian coins);

- on the 1 euro coin - Ivan Rilski, together with the Cyrillic inscription "Euro";

- on the 2-euro coin - Paisius of Hilendar - with the Cyrillic inscription "Euro";

- on each of the coins there will be an inscription in Cyrillic "Bulgaria";

- the 2-euro band will be written in Cyrillic "GOD, PROTECT BULGARIA!" - thus, according to the manager of Bulgarian Bank, the Bulgarian monetary tradition (dating back to the 13th century) will be respected in the coinage

The Bulgarian Cyrillic alphabet and the preservation of the "stotinka" (in the form of Bulgarian eurocents) will bring the new currency closer to the old Bulgarian lev.

Linguistic issues

.png.webp)

Bulgarian Cyrillic script and its non-straightforward transliteration of the word euro initially caused issues when the European Central Bank and European Commission insisted that Bulgaria adopt the name ЕУРО (i.e., euro), rather than the original ЕВРО (i.e., evro) Bulgarian pronunciation: [ˈɛvro] (from Bulgarian Европа [ɛvˈrɔpɐ], meaning Europe), arguing that the currency's name should be standardised across the EU as much as possible. Bulgaria maintained that its language's alphabet and phonetic orthography warranted the exception.[93] At the 2007 EU Summit in Lisbon, the issue was decided in Bulgaria's favour, making евро the official Cyrillic spelling from 13 December 2007.[94][95]

This ruling affected the design of euro banknotes. The second series of notes (beginning with the €5 note issued from 2013) includes the term "ЕВРО" and the abbreviation "ЕЦБ" (short for Европейска централна банка, the Bulgarian name of the European Central Bank).[96] The first series only had the standard Latin alphabet "EURO" and Greek "ΕΥΡΩ".

Because euro coins only have the Latin "EURO" on their common (reverse) side, Greek coins include the Greek spelling on the national (obverse) side. Bulgarian coins may follow suit, with "EURO" on one side and "ЕВРО" on the other.

The plural of евро in Bulgarian varies in spoken language – евро, евра [ɛvˈra], еврота [ˈɛvrotɐ] – but the most widespread form is евро – without inflection in plural form. The word for euro, though, has a normal form with the postpositive definite article – еврото ([ˈɛvroto], the euro).

The Bulgarian word for eurocent is евроцент [ˈɛvrot͡sɛnt] and it is likely to be that or цент [ˈt͡sɛnt] that is used when the European currency is introduced in Bulgaria. In contrast to euro, the word for "cent" has a full inflection in both the definite and the plural form: евроцент (basic form), евроцентът (full definite article – postpositive), евроцентове (plural) and 2 евроцента (numerative form – after numerals). However, the name of the Bulgarian lev subunit, stotinki (стотинки), and the singular stotinka (стотинка), could be used in place of cent, as it has become a synonym of the word "coins" in colloquial Bulgarian. Just like "cent" (from Latin centum), its etymology is from a word meaning hundred – sto (сто). Stotinki is used widely in the Bulgarian diaspora in Europe to refer to subunits of currencies other than the Bulgarian lev.

Public opinion

- Public support for the euro in Bulgaria[97]

References

- "Prof. Dr. Ivan Angelov: Bulgaria needs a managed floating exchange rate". Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- "Official: Bulgaria and Croatia Join the ERM II Exchange Rate Mechanism". Sofia News Agency Novinite. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Bulgaria, Croatia take vital step to joining euro". Reuters. 10 July 2020.

- "The draft National Plan for the Introduction of the Euro in the Republic of Bulgaria has been prepared in time". Ministry of Finance. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- Staff (30 June 2021). "Bulgaria sticks to plans to adopt the euro from Jan 1, 2024". Reuters. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- "Bulgaria sticks to plan to adopt the euro in 2024 amid coalition squabbles". Reuters. 27 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Bulgaria scraps January 2024 target for adopting euro". www.milletnews.com. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- "Bulgaria's budget of reform". The Sofia Echo. 30 November 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- "First check against euro zone criteria". The Sofia Echo. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "The Sofia Echo". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "Bulgaria's Eurozone accession drifts away". Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- "ЕК: Не приемаме никакви едностранни решения за въвеждане на еврото". Archived from the original on 6 December 2008.

- "Bulgaria could join euro zone ahead of other EU countries". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "said to pressure Bulgaria into discontinuing currency board".

- Dnevnik.bg (17 September 2009). "Bulgaria to seek eurozone entry within GERB's term – Finance Minister". The Sofia Echo. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Bulgaria Finance Minister Takes ERM 2 Application to Brussels Next Week – Novinite.com – Sofia News Agency". novinite.com.

- "IMF Mission to Audit Bulgaria's Fiscal Plans 2009–10". Novinite.com – Sofia News Agency.

- "Bulgaria drops goal of ERM2 entry in 2010". The Sofia Echo. 9 April 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- "Bulgaria delays eurozone application as deficit soars". Eubusiness.com. 9 April 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- "Bulgaria puts off Eurozone membership for 2015". Radio Bulgaria. 26 July 2011. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- "Bulgaria shelves euro membership plans". EUobserver.com. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- "Bulgaria Sees Euro Recovery to Boost Growth Quickly, Kostov Says". Bloomberg L.P. 15 January 2014.

- "Bulgaria says it will start talks to join the euro". 16 January 2015.

- "Bulgaria creates council for preparation for euro zone membership". The Sofia Globe. July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "Joining Euro to Have Positive Impact on Bulgaria's Economy – Experts". Sofia News Agency (Novinite). 19 January 2015.

- "Euro adoption to have only positive effect on Bulgaria: expert". Focus News Agency. 21 January 2015. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- "GERB leader Borissov: Bulgaria will apply to join euro zone". Sofia Globe. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "Bulgaria to know its chances for ERM-II accession by end-2017". Central European Financial Observer. 3 July 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- Bulgaria to take first steps towards euro, EUOBSERVER 11 January 2018

- Bulgaria expects to apply for eurozone waiting room by July, EURACTIV 11 January 2018

- "Defiant Bulgaria to push for ERM-2 membership". Reuters. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- Bulgaria renews calls for euro as it takes on EU presidency, Euronews 11 January 2018

- "Letter by Bulgaria on ERM II participation" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 29 June 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Statement on Bulgaria's path towards ERM II participation". Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Tsvetelia Tsolova, Catherine Evans (28 January 2019). "Bulgaria could join the euro early in 2022: finance minister". Reuters. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Bulgaria agrees to conditions for joining euro, Financial Times 12 July 2018

- "Bulgaria hopes to join euro zone 'waiting room' by end of April -minister". Financial Post. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Bulgaria on path to adopt euro in 2023: IMF's Georgieva". Reuters. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Bulgaria sees July decision on entering euro "waiting room"". Reuters. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Bulgaria's Euro Accession Dream Stumbles as Virus Spreads". Bloomberg L.P. 30 March 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "UPDATE 1-Bulgaria to apply to join euro zone's 'waiting room' by end April". Reuters. 10 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Georgiev, Yasen (20 April 2020). "Never let a good crisis go to waste (or why Bulgaria is speeding its way to the euro)". Emerging Europe. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Fitch Revises Bulgaria's Outlook to Stable; Affirms at 'BBB'". fitchratings.com. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Bulgaria has Officially Applied for the Eurozone". Sofia News Agency Novinite. 30 April 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Bulgaria is in ERM II from 10 July 2020– Dombrovskis". SeeNews. 12 May 2020.

- "Bulgaria gives up its goal to join eurozone in 2024". 17 February 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- "Bulgaria's far-right Vazrazhdane gathers 590,000 signatures for referendum on delaying euro adoption". 10 April 2023.

- "Bulgaria's Parliament rejects holding referendum on retaining the lev as sole currency". The Sofia Globe. 7 July 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- "Bulgarian parliament, euro referendum debate, boycotted by main parties". www.euractiv.com. 30 June 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- "Bulgaria's government sets new target dates for Schengen and Eurozone entry". 26 July 2023.

- "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "The corrective arm/ Excessive Deficit Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- "General government gross debt (EDP concept), consolidated - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Central Bank. May 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "Convergence Report - 2012" (PDF). European Commission. March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2012" (PDF). European Commission. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Convergence Report - 2013" (PDF). European Commission. March 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2013" (PDF). European Commission. February 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2014" (PDF). European Commission. March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Convergence Report - June 2016" (PDF). European Commission. June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2016" (PDF). European Commission. May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Convergence Report 2018". European Central Bank. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Convergence Report - May 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Convergence Report 2020" (PDF). European Central Bank. 1 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Convergence Report - June 2020". European Commission. June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2020". European Commission. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Convergence Report June 2022" (PDF). European Central Bank. 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Convergence Report 2022" (PDF). European Commission. 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Press release of the Bulgarian National Bank". 21 April 2005.

- Coin catalog : 1.95583 Leva (photos and details)

- "Новини от България и света, актуална информация 24 часа в денонощието". News.bg.

- "The Sofia Echo – The symbolic meaning of Bulgaria's national symbols". Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- "Bulgaria Debates National Symbol for Euro Coin Design". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- "Bulgaria singles out new national symbol by June 29". Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- "Bulgaria choses Madara horseman as its symbol". The Sofia Echo. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- "Bulgaria selected the new euro design". Info Bulgaria. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- "Bulgaria Chooses Madara Horseman for National Symbol at Euro Coin Design". Sofia News Agency Novinite. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- "Bulgaria chooses heritage site to adorn euro coins". EU Business. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- "(Interview of Mr. Dimitar Radev, Governor of the BNB, for BTA, July 24, 2023.)". www.bnb.bg. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- "letter to the editor". The Sofia Echo. 13 November 2006. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Bulgaria wins victory in "evro" battle". Reuters. 18 October 2007.

- Elena Koinova (19 October 2007). ""Evro" dispute over – Portuguese foreign minister". The Sofia Echo. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Superimpose – ECB – Our Money". ECB. ECB. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- "Public Opinion 1999–2020". European Commission. Retrieved 11 July 2020.