Commercial Lunar Payload Services

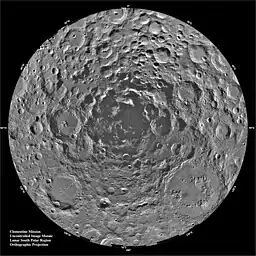

Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) is a NASA program to contract transportation services able to send small robotic landers and rovers to the Moon's south polar region mostly[1][2] with the goals of scouting for lunar resources, testing in situ resource utilization (ISRU) concepts, and performing lunar science to support the Artemis lunar program. CLPS is intended to buy end-to-end payload services between Earth and the lunar surface using fixed priced contracts.[3][4] The program was extended to add support for large payloads starting after 2025.

| Commercial Lunar Payload Services | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Models of the first three commercial landers selected for the program. Left to right: Peregrine by Astrobotic Technology, Nova-C by Intuitive Machines, and Z-01 by OrbitBeyond. | |

| Type of project | Aerospace |

| Products | Proposed: Peregrine, Artemis-7, Nova-C, McCandless Lunar Lander, Blue Ghost, XL-1, MX-1, MX-2, MX-5, MX-9, SERIES-2, Z-01 and Z-02 |

| Owner | NASA |

| Country | United States |

| Status | Active |

| Website | NASA.gov/commercial-lunar-payload-services |

NASA's Science Mission Directorate operates the CLPS program in conjunction with the Human Exploration and Operations and Space Technology Mission Directorates. NASA expects the contractors to provide all activities necessary to safely integrate, accommodate, transport, and operate NASA payloads, including launch vehicles, lunar lander spacecraft, lunar surface systems, Earth re-entry vehicles and associated resources.[4]

To date, eight missions have been contracted under the program (not counting one mission contract that was revoked after awarding and another mission contract that was cancelled after the contracted company went bankrupt).

History

NASA has been planning the exploration and use of natural lunar resources for many years. A variety of exploration, science, and technology objectives that could be addressed by regularly sending instruments, experiments and other small payloads to the Moon have been identified by NASA.[3]

When the concept study on the Resource Prospector rover was cancelled in April 2018, NASA officials explained that lunar surface exploration will continue in the future, but using commercial lander services under a new CLPS program.[5][6] Later that April, NASA launched the Commercial Lunar Payload Services program as the first step in the solicitation for flights to the Moon.[3][4][7] In April 2018, CLPS issued a Draft Request for Proposal,[4] and in September 2018 the actual CLPS Request for Proposal was issued.[8] The text of the formal solicitation and selected contractors are here:[8]

On 29 November 2018, NASA announced the first nine companies that will be allowed to bid on contracts,[9] which are indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contracts with a combined maximum contract value of $2.6 billion during the next 10 years.[9]

In February 2018 NASA issued a solicitation for Lunar Surface Instrument and Technology Payloads that may become CLPS customers. Proposals were due by November 2018 and January 17, 2019. NASA makes yearly calls for proposals.[10][11]

On May 31, 2019, NASA announced a list of awards, featuring Astrobotic, of Pittsburgh, Pa., $79.5 million; Intuitive Machines, of Houston, Texas, $77 million; and OrbitBeyond, $97 million; to launch their Moon landers.[12] However, Orbit Beyond dropped out of this contract in July 2019 (with NASA acknowledging termination of contract on 29 July 2019), but remains a contractor able to bid on future missions.[13]

On 1 July 2019, a US$5.6 million contract was awarded to Astrobotic and its partner Carnegie Mellon University to develop MoonRanger, a 13 kg (29 lb) rover to carry payloads on the Moon for NASA's CLPS.[14][15] Launch is envisioned for either 2021 or 2022.[15][16] The rover will carry science payloads yet to be determined and developed by other providers, that will focus on scouting and creating 3D maps of a polar region for signs of water ice or lunar pits for entrances to Moon caves.[16][17] The rover would operate mostly autonomously for up to one week.[17]

On 18 November 2019, NASA added five contractors to the group of companies eligible to bid to deliver large payloads to the lunar surface under the CLPS program: Blue Origin, Ceres Robotics, Sierra Nevada Corporation, SpaceX, and Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems.[18]

On 8 April 2020, NASA announced it had awarded the fourth (after Astrobotic's, Intuitive Machines' and OrbitBeyond's awards) CLPS contract for Masten Space Systems. The contract, worth US$75.9 million, is for Masten's XL-1 lunar lander to deliver payloads from NASA and other customers to the south pole of the Moon in late 2022.[19]

On 11 June 2020 NASA awarded Astrobotic Technology its second CLPS contract. The mission will be the first flight of Astrobotic's larger Griffin lander, delivering NASA's VIPER resource prospecting lunar rover to the Lunar south pole.[20] Griffin weighs 450 kg, the VIPER rover approximately 1,000 pounds (about 450 kg), and the award is for $199.5 M[20] (this covers Griffin lander and launch costs too). The mission is scheduled for November 2024.[21]

On 16 October 2020[22] NASA awarded Intuitive Machines their second CLPS contract for Intuitive Machines Mission 2 (IM-2). The contract was worth approximately $47 million. Using Nova-C lander, the mission will land a drill (PRIME-1) combined with a mass spectrometer to the Lunar south pole, to attempt harvesting ice from below the surface. The mission is scheduled for December 2022, using a Falcon 9 rocket.

On 4 February 2021, NASA awarded a CLPS contract to Firefly Aerospace, of Cedar Park, Texas, worth approximately US$93.3 million, to deliver a suite of 10 science investigations and technology demonstrations to the Moon in 2023 (later delayed to 2024). This was the sixth award (seventh if one counts the OrbitBeyond award that was later cancelled) for lunar surface delivery (that is, for a lunar lander) under the CLPS initiative. This was the first delivery awarded to Firefly Aerospace, which will provide the lunar delivery service using its Blue Ghost lander, which the company designed and developed at its Cedar Park facility.[23]

The next (7th, not counting OrbitBeyond contract) CLPS contract was awarded by NASA on 17 November 2021 to Intuitive Machines, their 3rd award. Their Nova-C lander was contracted to land four NASA payloads (about 92 kg in total) to study a lunar feature called Reiner Gamma. The mission was known as IM-3 mission and was planned to land on the Moon in 2024. The contract value was $77.5 million and under the contract, Intuitive Machines was responsible for end-to-end delivery services, including payload integration, delivery from Earth to the surface of the Moon, and payload operations.[24]

On July 21, 2022, NASA announced that it had awarded a CLPS contract (8th, not counting OrbitBeyond) worth $73 million to a team led by Draper. The mission targets Schrödinger Basin on the farside of the Moon and at the time was scheduled for 2025. The mission lander, called SERIES-2 by Draper, will deliver to Schrödinger Basin three experiments to collect seismic data, measure the heat flow and electrical conductivity of the lunar subsurface and measure electromagnetic phenomena created by the interaction of the solar wind and plasma with the lunar surface. This mission is the first CLPS mission to target the lunar farside, and aims to be the second landing of all time (after China's Chang’e-4) to the Moon's farside. The mission will also develop and deploy two data relay satellites, a must for missions in the lunar farside. Many companies are involved in the mission with Draper being the prime contractor, including ispace.[25] On September 29, 2023, ispace announced that the SERIES-2 lander had been comprehensively redesigned and renamed as APEX 1.0, causing the mission to be delayed to 2026.[26]

Masten Space Systems filed for bankruptcy in July 2022,[27] with nearly all of their assets sold to Astrobotic Technology.[28] This led to the cancellation of Masten's CLPS mission.

On March 14, 2023, NASA awarded Firefly a $112 million task order (8th CLPS contract, not counting OrbitBeyond or Masten Space Systems) for a mission to the far side of the Moon using the second Blue Ghost lander, which is expected to launch in 2026.[29]

Overview

The competitive nature of the CLPS program is expected to reduce the cost of lunar exploration, accelerate a robotic return to the Moon, sample return, resource prospecting in the south polar region, and promote innovation and growth of related commercial industries.[32] The payload development program is called Development and Advancement of Lunar Instrumentation (DALI), and the payload goals are exploration, in situ resource utilization (ISRU), and lunar science. The first instruments were expected to be selected by Summer 2019,[4] and the flight opportunities were expected to start in 2021.[32][4]

Multiple contracts will be issued, and the early payloads will likely be small because of the limited capacity of the initial commercial landers.[7] The first landers and rovers will be technology demonstrators on hardware such as precision landing/hazard avoidance, power generation (solar and RTGs), in situ resource utilization (ISRU), cryogenic fluid management, autonomous operations and sensing, and advanced avionics, mobility, mechanisms, and materials.[4] This program requires that only US launch vehicles can launch the spacecraft.[4] The mass of the landers and rovers can range from miniature to 1,000 kg (2,200 lb),[33] with a 500 kg (1,100 lb) lander targeted to launch in 2022.[32]

The Draft Request for Proposal's covering letter states that the contracts will last up to 10 years. As NASA's need to send payloads to the lunar surface (and other cislunar destinations) arises it will issue Firm-Fixed Price 'task orders' that the approved prime contractors can bid for. A Scope Of Work will be issued with each task order. The CLPS proposals are being evaluated against five Technical Accessibility Standards.[4]

NASA is assuming a cost of one million dollars per kilogram delivered to the lunar surface. (This figure may be revised after a lunar landing when the actual costs are available.)[34]

Contractors

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The companies selected are considered "main contractors" that can sub-contract projects to other companies of their choice. The first companies granted the right to bid on CLPS contracts were chosen in 2018.[9][35][8]

On 21 May 2019, three companies were awarded lander contracts: Astrobotic Technology, Intuitive Machines, OrbitBeyond.[12]

On 29 July 2019, NASA announced that it had granted OrbitBeyond's request to be released from this specific contract, citing "internal corporate challenges."[36]

On 18 November 2019, NASA added five new contractors to the group of companies who are eligible to bid to send large payloads to the surface of the Moon with the CLPS program.[18]

On 8 April 2020, NASA selected Masten Space Systems for a mission to deliver and operate eight payloads – with nine science and technology instruments – to the Moon’s South Pole in 2022.[37][38][39] Masten Space Systems filed for bankruptcy in July 2022;[27][28] this led to the cancellation of Masten's CLPS mission.

On 4 February 2021, NASA awarded a CLPS contract to Firefly Aerospace for a mission deliver a suite of 10 science investigations and technology demonstrations to the Moon in 2023.[23]

On 21 July 2022, NASA announced that it had awarded a CLPS contract to Draper Laboratories.[25]

| Selection date | Company | Headquarters | Proposed services | First awarded contract |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 November 2018 | Astrobotic Technology | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | Peregrine and Griffin landers | 31 May 2019 |

| Deep Space Systems | Littleton, Colorado | Rover; design and development services | ||

| Draper Laboratory | Cambridge, Massachusetts | originally proposed Artemis-7 lander; contract awarded for SERIES-2 lander | 21 July 2022 | |

| Firefly Aerospace | Cedar Park, Texas | Blue Ghost lander[40][41] | 4 February 2021 | |

| Intuitive Machines | Houston, Texas | Nova-C lander | 31 May 2019 | |

| Lockheed Martin Space | Littleton, Colorado | McCandless Lunar Lander | ||

| Masten Space Systems | Mojave, California | XL-1 lander | 8 April 2020 | |

| Moon Express | Cape Canaveral, Florida | MX-1, MX-2, MX-5, MX-9 landers; sample return. | ||

| OrbitBeyond | Edison, New Jersey | Z-01 and Z-02 landers | [note 1] | |

| 18 November 2019 | Blue Origin | Kent, Washington | Blue Moon lander | |

| Ceres Robotics | Palo Alto, California | |||

| Sierra Nevada Corporation | Louisville, Colorado | |||

| SpaceX | Hawthorne, California | Starship | ||

| Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems | Irvine, California |

Notes:

- Contract awarded 31 May 2019 and withdrawn 29 July 2019

Payload selection

The CLPS contracts for landers and lander missions do not include the payloads themselves. The payloads are developed under separate contracts either at NASA facilities or in commercial facilities. The CLPS landers provide landing, support services, and sample return as specified in each individual contract.

The first batch of science payloads are being developed in NASA facilities, due to the short time available before the first planned flights. Subsequent selections include payloads provided by universities and industry. Calls for payloads are planned to be released each year for additional opportunities.

First batch

The first twelve NASA payloads and experiments were announced on February 21, 2019,[42][43] and will fly on separate missions. As of February 2021 NASA has awarded contracts for four CLPS lander missions to support these payloads.

- Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer, to monitor the lunar surface radiation.

- Magnetometer, to measure the surface magnetic field.

- Low-frequency Radio Observations from the Near Side Lunar Surface, a radio experiment to measure photoelectron sheath density near the surface.

- A set of three instruments to collect data during entry, descent and landing on the lunar surface to help develop future crewed landers.

- Stereo Cameras for Lunar Plume-Surface Studies is a set of cameras for monitoring the interaction between the lander engine plume and the lunar surface.

- Surface and Exosphere Alterations by Landers, another landing monitor to study the effects of spacecraft on the lunar exosphere.

- Navigation Doppler Lidar for Precise Velocity and Range Sensing is a velocity and ranging lidar instrument designed to make lunar landings more precise.

- Near-Infrared Volatile Spectrometer System, is an imaging spectrometer to analyze the composition of the lunar surface.

- Neutron Spectrometer System and Advanced Neutron Measurements at the Lunar Surface, are a pair of neutron detectors to quantify the hydrogen -and therefore water near the surface.

- Ion-Trap Mass Spectrometer for Lunar Surface Volatiles, is a mass spectrometer for measuring volatiles on the surface and in the exosphere.

- Solar Cell Demonstration Platform for Enabling Long-Term Lunar Surface Power, a next-generation solar array for long-term missions.

- Lunar Node 1 Navigation Demonstrator, a navigation beacon for providing geolocation for orbiters and landing craft.

Second batch

On July 1, 2019, NASA announced the selection of twelve additional payloads, provided by universities and industry. Seven of these are scientific investigations while five are technology demonstrations.[44]

- MoonRanger, a small, fast-moving rover that has the capability to drive beyond communications range with a lander and then return to it. Astrobotic Technology, Inc.

- Heimdall, a flexible camera system for conducting lunar science on commercial vehicles. Planetary Science Institute.

- Lunar Demonstration of a Reconfigurable, Radiation Tolerant Computer System, which will demonstrate a radiation-tolerant computing technology. Montana State University.

- Regolith Adherence Characterization (RAC) Payload, which will determine how lunar regolith sticks to a range of materials exposed to the Moon's environment. Alpha Space Test and Research Alliance, LLC.

- The Lunar Magnetotelluric Sounder, which will characterize the structure and composition of the Moon's mantle by studying electric and magnetic fields. Southwest Research Institute. Currently part of the Lunar Interior Temperature and Materials Suite planned for launch in 2024.[45]

- The Lunar Surface Electromagnetics Experiment (LuSEE), which will make comprehensive measurements of electromagnetic phenomena on the surface of the Moon. University of California, Berkeley.

- The Lunar Environment heliospheric X-ray Imager (LEXI), which will capture images of the interaction of Earth's magnetosphere with solar wind. Boston University.

- Next Generation Lunar Retroreflectors (NGLR), which will serve as a target for lasers on Earth to precisely measure the Earth-Moon distance. University of Maryland.

- Lunar Compact InfraRed Imaging System (L-CIRiS), an infrared radiometer to explore the Moon's surface composition and temperature distribution. University of Colorado.

- The Lunar Instrumentation for Subsurface Thermal Exploration with Rapidity (LISTER), an instrument designed to measure heat flow from the interior of the Moon. Texas Tech University. Currently part of the Lunar Interior Temperature and Materials Suite planned for launch in 2024.[45]

- PlanetVac, a technology for acquiring and transferring lunar regolith from the surface to other instruments or place it in a container for its potential return to Earth. Honeybee Robotics, Ltd.

- SAMPLR: Sample Acquisition, Morphology Filtering, and Probing of Lunar Regolith, a sample acquisition technology that will make use of a robotic arm. Maxar Technologies.

Third batch

In June 2021, NASA announced the selection of three payloads from its Payloads and Research Investigations on the Surface of the Moon (PRISM) call for proposals. These payloads will be sent to Reiner Gamma and Schrödinger Basin in the 2023–2024 timeframe.[45]

- Lunar Vertex: a joint lander and rover payload suite slated for delivery to Reiner Gamma to investigate lunar swirls. Applied Physics Laboratory.

- Farside Seismic Suite (FSS): two seismometers, the vertical Very Broadband seismometer and the Short Period sensor, will measure seismic activity on the far side of the Moon at Schrödinger Basin. Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- Lunar Interior Temperature and Materials Suite (LITMS): two instruments, the Lunar Instrumentation for Subsurface Thermal Exploration with Rapidity pneumatic drill and the Lunar Magnetotelluric Sounder, previously selected in the second batch and slated for delivery to Schrödinger Basin. Will complement data acquired by the FSS. Southwest Research Institute.

List of missions announced under CLPS

Missions contracted

Orbit Beyond returned their task order (cancelling their mission) two months after award in 2019.[20] That mission is not listed below.

| No | Name | Launch | Contractor | Lander | Launch Vehicle | Awarded | Lunar Destination |

Notes | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLPS-1 | Peregrine Mission One | 24 December 2023[46] | Astrobotic Technology | Peregrine | Vulcan | May 2019 | Gruithuisen Domes[47] | Will carry 28 payloads, including 14 NASA payloads contracted under CLPS.[48] NASA awarded $79.5 M.[49] Peregrine mass 1,283 kg, payload mass up to 256 kg. | Planned |

| CLPS-2 | Intuitive Machines Mission 1 (IM-1) | 12 January 2024[50] | Intuitive Machines | Nova-C | Falcon 9 | May 2019[20] | near the South Pole[51] | Will carry up to five NASA contracted payloads as well as payloads from other customers. The spacecraft will operate for up to 14 days after landing.[52][53] | Planned |

| CLPS-3 | Intuitive Machines Mission 2 (IM-2) | Q1 2024[54] | Intuitive Machines | Nova-C | Falcon 9 | October 2020[22] | South Pole | Will land a drill (PRIME-1) combined with a mass spectrometer, to attempt harvesting ice from below the surface. | Planned |

| Intuitive Machines Mission 3 (IM-3) | Q2 2024 | Intuitive Machines | Nova-C | Falcon 9 | November 2021[55][24] | Reiner Gamma | IM-3 will carry 203 lbs (92 kg) of payload to the Moon, including the ESA provided MoonLIGHT lunar laser retroreflector payload.[56] | Planned | |

| VIPER | November 2024[21] | Astrobotic Technology | Griffin | Falcon Heavy | June 2020 | Nobile Crater | First flight of Astrobotic's larger Griffin lander. Will deliver NASA's VIPER resource prospecting lunar rover.[20] Griffin is 450 kg; the award is for $199.5 million[20] (this covers Griffin lander and launch costs too). | Planned | |

| Blue Ghost M1 | 2024[57] | Firefly Aerospace | Blue Ghost | Falcon 9 [58] |

February 2021[59] | Mare Crisium | Will land ten payloads.[60] | Planned | |

| CLPS-12 | TBA | 2026[26] | Draper Laboratory | APEX 1.0 | TBA | July 2022 | Schrödinger Basin | LuSEE-Lite, a flight spare from the FIELDS instrument on the Parker Solar Probe, will fly on this mission.[56] | Planned |

| CS-3 | Blue Ghost M2 | 2026 | Firefly Aerospace | Blue Ghost | TBA | March 2023 | Far side of the Moon | ESA communications and data relay satellite to lunar orbit, LuSEE-Night (a radio telescope pathfinder) and User Terminal (a communication technology demonstrator) the to the far side of the Moon.[61] | Planned |

Missions announced but not yet contracted

| No | Name | Launch | Contractor | Lander | Launch Vehicle | Awarded | Lunar Destination |

Notes | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBA | Q4 2025 – Q1 2026 | TBA | TBA | TBA | South Pole | ESA's Package for Resource Observation and in-Situ Prospecting for Exploration, Commercial exploitation, and Transportation (PROSPECT) payload will fly on this mission.[62] | Planned |

Cancelled Missions

| No | Name | Launch | Contractor | Lander | Launch Vehicle | Awarded | Lunar Destination |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masten Mission One | Intended: November 2023 | Masten Space | XL-1 | Falcon 9 [63] |

April 2020[64] | South Pole | Intended to deliver several hundred kg of payloads.[65][66] Masten Space filed for bankruptcy in July 2022,[27] with nearly all of their assets sold to Astrobotic Technology.[28] |

See also

- Commercial Orbital Transportation Services – Former NASA program

- Lunar CATALYST

- Lunar Gateway – Lunar orbital space station under development

- Lunar water – Presence of water on the Moon

- NewSpace – Spaceflight not paid for by a government agency

References

- NASA taps 3 companies for commercial moon missions Archived February 26, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. William Harwood, CBS News. 31 May 2019.

- Foust, Jeff (May 31, 2019). "NASA awards contracts to three companies to land payloads on the moon". Space News. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- "NASA Expands Plans for Moon Exploration: More Missions, More Science". NASA. April 30, 2018. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- "Draft Commercial Lunar Payload Services - CLPS solicitation". Federal Business Opportunities. NASA. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- Foust, Jeff (May 4, 2018). "NASA argues Resource Prospector no longer fit into agency's lunar exploration plans". Space News. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- NASA emphasizes commercial lunar lander plans with Resource Prospector cancellation Archived October 18, 2018, at WebCite. Jeff Foust, Space News. 28 April 2018.

- NASA cancels lunar rover, shifts focus to commercial moon landers Archived June 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Stephen Clark, Space News. 1 June 2018.

- "Commercial Lunar Payload Services

Solicitation Number: 80HQTR18R0011R". Federal Business Opportunities. NASA. Archived from the original on May 9, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2019. - "NASA Announces New Partnerships for Commercial Lunar Payload Delivery Services". NASA.GOV. NASA. November 29, 2018. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- "NASA Calls for Instruments, Technologies for Delivery to the Moon". NASA. October 18, 2018. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- "Lunar Surface Instrument and Technology Payloads". NSPIRES - NASA Solicitation and Proposal Integrated Review and Evaluation System. NASA. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- "NASA chooses three companies to send landers to the moon". UPI. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Private Company Orbit Beyond Drops Out of 2020 NASA Moon-Landing Deal. Archived April 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Mike Wall, Space.com. 30 July 2019.

- Astrobotic Awarded US$5.6 Million NASA Contract to Deliver Autonomous Moon Rover Archived March 6, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Astrobotic 1 July 2019

- Astrobotic gets $5.6m NASA contract to develop MoonRanger rover Archived October 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Brittany A. Roston, Slash Gear 1 July 2019

- Astrobotic awarded NASA funding to build autonomous rover Archived October 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Julia Mericle, Pittsburgh Business Times 2 July 2019

- NASA Selects Carnegie Mellon, Astrobotic To Build Lunar Robot Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Byron Spice, Carnegie Mellon University 3 July 2019

- Grush, Loren (November 18, 2019). "NASA partners with SpaceX, Blue Origin, and more to send large payloads to the Moon 5 - The companies are aiming to land in the early 2020s". The Verge. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Foust, Jeff (April 8, 2020). "Masten wins NASA lunar lander award". Space News. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- "Astrobotic Awarded $199.5 Million Contract to Deliver NASA Moon Rover | Astrobotic". Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- "NASA Replans CLPS Delivery of VIPER to 2024 to Reduce Risk". NASA. July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- Brown, Katherine (October 16, 2020). "NASA Selects Intuitive Machines to Land Water-Measuring Payload on the Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- "NASA Selects Firefly Aerospace for Artemis Commercial Moon Delivery in 2023". NASA. February 4, 2021. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "NASA Selects Intuitive Machines for New Lunar Science Delivery". NASA (Press release). November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- "Draper wins NASA contract for farside lunar lander mission". July 22, 2022.

- Foust, Jeff (September 29, 2023). "Ispace revises design of lunar lander for NASA CLPS mission". SpaceNews. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- Foust, Jeff (July 29, 2022). "Masten Space Systems files for bankruptcy". SpaceNews. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- Foust, Jeff (September 11, 2022). "Court approves sale of Masten assets to Astrobotic". SpaceNews. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- Foust, Jeff (March 15, 2023). "Firefly wins second NASA CLPS mission". SpaceNews. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- Why the Lunar South Pole? Archived September 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Adam Hugo. The Space Resource. 25 April 2029.

- Lunar Resources: Unlocking the Space Frontier. Archived July 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Paul D. Spudis. Ad Astra, Volume 23 Number 2, Summer 2011. Published by the National Space Society. Retrieved on 16 July 2019.

- "NASA Expands Plans for Moon Exploration: More Missions, More Science". SpaceRef. May 3, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- Werner, Debra (May 24, 2018). "NASA to begin buying rides on commercial lunar landers by year's end]". Space News. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- Report Series: Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Science (2019). Review of the Commercial Aspects of NASA SMD's Lunar Science and Exploration. The National Academies Press. p. 15. doi:10.17226/25374. ISBN 978-0-309-48928-7. S2CID 240868930. Archived from the original on February 10, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- Draft Concepts for Commercial Lunar Landers Archived August 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. NASA, CLPS. Accessed on 12 December 2018.

- "Commercial lunar lander company terminates NASA contract". SpaceNews.com. July 30, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- "NASA Awards Contract to Deliver Science, Tech to Moon". April 8, 2020. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- "Masten wins NASA lunar lander award". April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "Masten Space Systems Awarded $76M to Help NASA Deliver Lunar Sci-Tech Payloads". April 9, 2020. Archived from the original on May 9, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- Jeff Foust (July 9, 2019). "Firefly to partner with IAI on lunar lander". Space News. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- Foust, Jeff (February 4, 2021). "Firefly wins NASA CLPS lunar lander contract". SpaceNews. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- NASA selects experiments to fly aboard commercial lunar landers Archived July 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Derek Richardson, Spaceflight Insider. February 26, 2019,

- NASA picks 12 lunar experiments that could fly this year Archived February 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. David Szondy, New Atlas. 21 February 2019.

- NASA Selects 12 New Lunar Science, Technology Investigations Archived August 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Grey Hautaluoma, NASA Headquarters Press Release 19-053. July 1, 2019

- "NASA Selects New Science Investigations for Future Moon Deliveries". NASA (Press release). June 10, 2021. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Baylor, Michael. "Vulcan VC2 - Peregrine Mission One & KuiperSat". Next Spaceflight. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- Foust, Jeff (February 2, 2023). "NASA changes landing site for Peregrine lunar lander". Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- Berger, Eric (June 25, 2021). "Rocket Report: China to copy SpaceX's Super Heavy? Vulcan slips to 2022". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- "Astrobotic Awarded $79.5 Million Contract to Deliver 14 NASA Payloads to the Moon | Astrobotic". Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- "Intuitive Machines Sets January 2024 for Historic U.S. Lunar Mission". Intuitive Machines (Press release). October 27, 2023. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- "NASA Redirects Intuitive Machines' First Mission to the Lunar South Pole Region". Intuitive Machines. February 6, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- "Intuitive Machines-1 Orbital Debris Assessment Report (ODAR) Revision 1.1" (PDF). Intuitive Machines. FCC. April 22, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- Etherington, Darrell (April 13, 2020). "Intuitive Machines picks a launch date and landing site for 2021 Moon cargo delivery mission". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- "Falcon 9 Block 5 - PRIME-1 (IM-2)". Next Spaceflight. July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- "NASA Selects Intuitive Machines to Deliver 4 Lunar Payloads in 2024". Intuitive Machines. November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- "Amendment 68: New Opportunity in ROSES: E.11 Payloads and Research Investigations on the Surface of the Moon (PRISM)" (PDF). NSPIRES. November 5, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 9, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- "Firefly Completes Integration Readiness Review of its Blue Ghost Lunar Lander". Firefly Aerospace. April 26, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- "Firefly Aerospace Awards Contract to SpaceX to Launch Blue Ghost Mission to Moon in 2023". Business Wire. May 20, 2021. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- "NASA Selects Firefly Aerospace for Artemis Commercial Moon Delivery in 2023". NASA (Press release). February 4, 2021. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- "Lunar Lander". Firefly Aerospace. February 1, 2021. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- "Blue Ghost Mission 2". Firefly Aerospace. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- "Amendment 34: Payloads and Research Investigations on the Surface of the Moon (PRISM) final text and due dates" (PDF). NSPIRES. September 2, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- SpaceX to Launch Masten Lunar Mission in 2022 Archived September 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Meagan Crawford, Masten Press Release. August 26, 2020.

- "Masten wins NASA lunar lander award". April 8, 2020.

- "XL-1 — Masten Space Systems". Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- "Masten Space Systems". Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

.svg.png.webp)