Pioneer 11

Pioneer 11 (also known as Pioneer G) is a NASA robotic space probe launched on April 5, 1973, to study the asteroid belt, the environment around Jupiter and Saturn, solar winds, and cosmic rays.[2] It was the first probe to encounter Saturn, the second to fly through the asteroid belt, and the second to fly by Jupiter. Later, Pioneer 11 became the second of five artificial objects to achieve an escape velocity allowing it to leave the Solar System. Due to power constraints and the vast distance to the probe, the last routine contact with the spacecraft was on September 30, 1995, and the last good engineering data was received on November 24, 1995.[3][4]

An artist's impression of a Pioneer spacecraft on its way to interstellar space. | |

| Mission type | Planetary and heliosphere exploration |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / ARC |

| COSPAR ID | 1973-019A |

| SATCAT no. | 6421 |

| Website | Pioneer Project website (archived) NASA Archive page |

| Mission duration | 22 years, 7 months and 19 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | TRW |

| Launch mass | 258.5 kg[1] |

| Power | 155 watts (at launch) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | April 6, 1973, 02:11:00 UTC[1] |

| Rocket | Atlas SLV-3D Centaur-D1A Star-37E |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-36B |

| End of mission | |

| Last contact | November 24, 1995 |

| Flyby of Jupiter | |

| Closest approach | December 3, 1974 |

| Distance | 43,000 kilometers (27,000 miles) |

| Flyby of Saturn | |

| Closest approach | September 1, 1979 |

| Distance | 21,000 kilometers (13,000 miles) |

| |

Mission background

History

Approved in February 1969, Pioneer 11 and its twin probe, Pioneer 10, were the first to be designed for exploring the outer Solar System. Yielding to multiple proposals throughout the 1960s, early mission objectives were defined as:

- Explore the interplanetary medium beyond the orbit of Mars

- Investigate the nature of the asteroid belt from the scientific standpoint and assess the belt's possible hazard to missions to the outer planets.

- Explore the environment of Jupiter.

Subsequent planning for an encounter with Saturn added many more goals:

- Map the magnetic field of Saturn and determine its intensity, direction, and structure.

- Determine how many electrons and protons of various energies are distributed along the trajectory of the spacecraft through the Saturn system.

- Map the interaction of the Saturn system with the solar wind.

- Measure the temperature of Saturn's atmosphere and that of Titan, the largest satellite of Saturn.

- Determine the structure of the upper atmosphere of Saturn where molecules are expected to be electrically charged and form an ionosphere.

- Map the thermal structure of Saturn's atmosphere by infrared observations coupled with radio occultation data.

- Obtain spin-scan images of the Saturnian system in two colors during the encounter sequence and polarimetry measurements of the planet.

- Probe the ring system and the atmosphere of Saturn with S-band radio occultation.

- Determine more precisely the masses of Saturn and its larger satellites by accurate observations of the effects of their gravitational fields on the motion of the spacecraft.

- As a precursor to the Mariner Jupiter/Saturn mission, verify the environment of the ring plane to find out where it may be safely crossed by the Mariner spacecraft without serious damage.[5]

Pioneer 11 was built by TRW and managed as part of the Pioneer program by NASA Ames Research Center.[6] A backup unit, Pioneer H, is currently on display in the "Milestones of Flight" exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.[7] Many elements of the mission proved to be critical in the planning of the Voyager program.[8]: 266–8

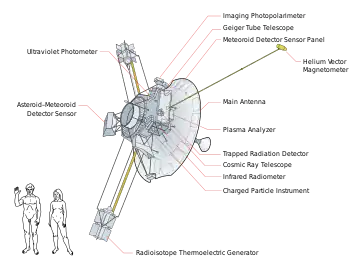

Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft diagram

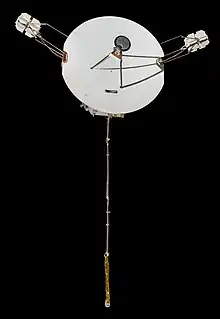

Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft diagram Reconstructed full-scale mock-up Pioneer 10 / 11 spacecraft at the National Air and Space Museum

Reconstructed full-scale mock-up Pioneer 10 / 11 spacecraft at the National Air and Space Museum Side view of the spacecraft

Side view of the spacecraft Pioneer 11 during the installation of its protective shroud

Pioneer 11 during the installation of its protective shroud

Spacecraft design

The Pioneer 11 bus measures 36 centimeters (14 in) deep and with six 76-centimeter-long (30 in) panels forming the hexagonal structure. The bus houses propellant to control the orientation of the probe and eight of the twelve scientific instruments. The spacecraft has a mass of 259 kilograms.[2]: 42

Attitude control and propulsion

- Orientation of the spacecraft was maintained with six 4.5-N,[9] hydrazine monopropellant thrusters: pair one maintains a constant spin-rate of 4.8 rpm, pair two controls the forward thrust, pair three controls attitude. Information for the orientation is provided by performing conical scanning maneuvers to track Earth in its orbit,[10] a star sensor able to reference Canopus, and two Sun sensors.[2]: 42–43

Communications

- The space probe includes a redundant system transceivers, one attached to the high-gain antenna, the other to an omni-antenna and medium-gain antenna. Each transceiver is 8 watts and transmits data across the S-band using 2110 MHz for the uplink from Earth and 2292 MHz for the downlink to Earth with the Deep Space Network tracking the signal. Prior to transmitting data, the probe uses a convolutional encoder to allow correction of errors in the received data on Earth.[2]: 43

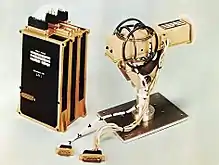

Power

- Pioneer 11 uses four SNAP-19 radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) (see diagram). They are positioned on two three-rod trusses, each 3 meters (9 feet 10 inches) in length and 120 degrees apart. This was expected to be a safe distance from the sensitive scientific experiments carried on board. Combined, the RTGs provided 155 watts at launch, and decayed to 140 W in transit to Jupiter. The spacecraft requires 100 W to power all systems.[2]: 44–45

Computer

- Much of the computation for the mission was performed on Earth and transmitted to the probe, where it is able to retain in memory, up to five commands of the 222 possible entries by ground controllers. The spacecraft includes two command decoders and a command distribution unit, a very limited form of a processor, to direct operations on the spacecraft. This system requires that mission operators prepare commands long in advance of transmitting them to the probe. A data storage unit is included to record up to 6,144 bytes of information gathered by the instruments. The digital telemetry unit is then used to prepare the collected data in one of the thirteen possible formats before transmitting it back to Earth.[2]: 38

Scientific instruments

Pioneer 11 has one additional instrument more than Pioneer 10, a flux-gate magnetometer.[11]

| Helium Vector Magnetometer (HVM) | |

|---|---|

|

Measures the fine structure of the interplanetary magnetic field, mapped the Jovian magnetic field, and provides magnetic field measurements to evaluate solar wind interaction with Jupiter.[12]

|

| Quadrispherical Plasma Analyzer | |

|

Peer through a hole in the large dish-shaped antenna to detect particles of the solar wind originating from the Sun.[13]

|

| Charged Particle Instrument (CPI) | |

|

Detects cosmic rays in the Solar System.[15]

|

| Cosmic Ray Telescope (CRT) | |

|

Collects data on the composition of the cosmic ray particles and their energy ranges.[16]

|

| Geiger Tube Telescope (GTT) | |

|

Surveys the intensities, energy spectra, and angular distributions of electrons and protons along the spacecraft's path through the radiation belts of Jupiter and Saturn.[17]

|

| Trapped Radiation Detector (TRD) | |

|

Includes an unfocused Cerenkov counter that detects the light emitted in a particular direction as particles passed through it recording electrons of energy, 0.5 to 12 MeV, an electron scatter detector for electrons of energy, 100 to 400 keV, and a minimum ionizing detector consisting of a solid-state diode that measured minimum ionizing particles (<3 MeV) and protons in the range of 50 to 350 MeV.[18]

|

| Meteoroid Detectors | |

|

Twelve panels of pressurized cell detectors mounted on the back of the main dish antenna record penetrating impacts of small meteoroids.[19]

|

| Asteroid/Meteoroid Detector (AMD) | |

|

Meteoroid-asteroid detector looks into space with four non-imaging telescopes to track particles ranging from close by bits of dust to distant large asteroids.[20]

|

| Ultraviolet Photometer | |

|

Ultraviolet light is sensed to determine the quantities of hydrogen and helium in space and on Jupiter and Saturn.[21]

|

| Imaging Photopolarimeter (IPP) | |

|

The imaging experiment relies upon the spin of the spacecraft to sweep a small telescope across the planet in narrow strips only 0.03 degrees wide, looking at the planet in red and blue light. These strips are then processed to build up a visual image of the planet.[22]

|

| Infrared Radiometer | |

|

Provides information on cloud temperature and the output of heat from Jupiter and Saturn.[23]

|

| Triaxial Fluxgate Magnetometer | |

|

Measures the magnetic fields of both Jupiter and Saturn. This instrument is not carried on Pioneer 10.[24]

|

Mission profile

_launch.jpg.webp)

Launch and trajectory

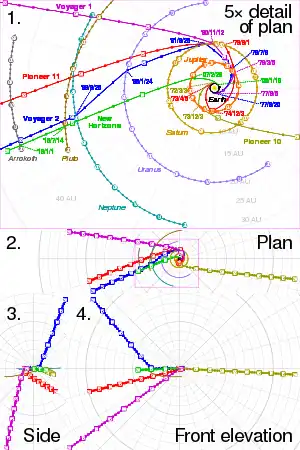

The Pioneer 11 probe was launched on April 6, 1973, at 02:11:00 UTC, by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration from Space Launch Complex 36A at Cape Canaveral, Florida aboard an Atlas-Centaur launch vehicle, with a Star-37E propulsion module. Its twin probe, Pioneer 10, had been launched a year earlier on March 3, 1972.

Pioneer 11 was launched on a trajectory directly aimed at Jupiter without any prior gravitational assists.[25] In May 1974, Pioneer was retargeted to fly past Jupiter on a north–south trajectory, enabling a Saturn flyby in 1979. The maneuver used 17 pounds of propellant, lasted 42 minutes and 36 seconds, and increased Pioneer 11's speed by 230 km/h.[26] It also made two mid-course corrections, on April 11, 1973 and November 7, 1974.[4][27]

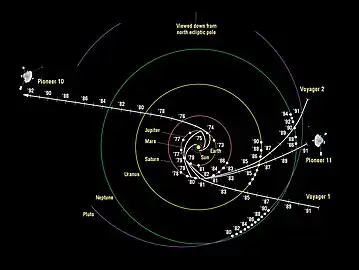

NASA map showing trajectories of the Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2 spacecraft.

NASA map showing trajectories of the Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2 spacecraft.

Animation of Pioneer 11 around Saturn

Animation of Pioneer 11 around Saturn

Pioneer 11 · Saturn · Epimetheus · Janus · Mimas · Enceladus

Encounter with Jupiter

Pioneer 11 flew past Jupiter in November and December 1974. During its closest approach, on December 2, it passed 42,828 kilometers (26,612 mi) above the cloud tops.[28] The probe obtained detailed images of the Great Red Spot, transmitted the first images of the immense polar regions, and determined the mass of Jupiter's moon Callisto. Using the gravitational pull of Jupiter, a gravity assist was used to alter the trajectory of the probe towards Saturn and gain velocity. On April 16, 1975, following the Jupiter encounter, the micrometeoroid detector was turned off.[4]

Pioneer 11 Jupiter encounter

Pioneer 11 Jupiter encounter Approach on Jupiter

Approach on Jupiter The Great Red Spot imaged by Pioneer 11

The Great Red Spot imaged by Pioneer 11 The Great Red Spot prior to closest approach

The Great Red Spot prior to closest approach Cloud bands along the edge of Jupiter

Cloud bands along the edge of Jupiter Beginning polar gravity assist

Beginning polar gravity assist Jupiter polar region from 1,079,000 km

Jupiter polar region from 1,079,000 km Io imaged from 756,000 km

Io imaged from 756,000 km

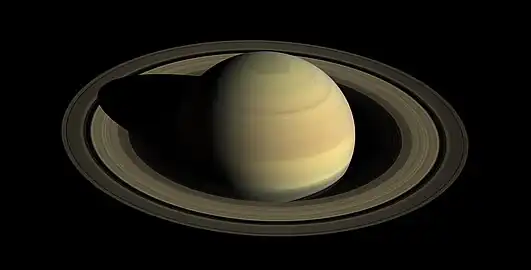

Saturn encounter

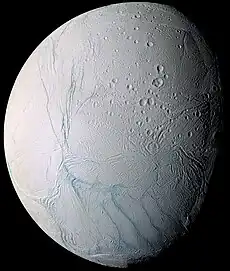

Pioneer 11 passed by Saturn on September 1, 1979, at a distance of 21,000 km from Saturn's cloud tops.

By this time, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 had already passed Jupiter and were also en route to Saturn, so it was decided to target Pioneer 11 to pass through the Saturn ring plane at the same position that the soon-to-come Voyager probes would use in order to test the route before the Voyagers arrived. If there were faint ring particles that could damage a probe in that area, mission planners felt it was better to learn about it via Pioneer. Thus, Pioneer 11 was acting as a "pioneer" in a true sense of the word; if danger were detected, then the Voyager probes could be rerouted further away from the rings, but missing the opportunity to visit Uranus and Neptune in the process.

Pioneer 11 imaged and nearly collided with one of Saturn's small moons, passing at a distance of no more than 4,000 kilometers (2,500 mi). The object was tentatively identified as Epimetheus, a moon discovered the previous day from Pioneer's imaging, and suspected from earlier observations by Earth-based telescopes. After the Voyager flybys, it became known that there are two similarly sized moons (Epimetheus and Janus) in the same orbit, so there is some uncertainty about which one was the object of Pioneer's near-miss. Pioneer 11 encountered Janus on September 1, 1979 at 14:52 UTC at a distance of 2500 km and Mimas at 16:20 UTC the same day at 103000 km.

Besides Epimetheus, instruments located another previously undiscovered small moon and an additional ring, charted Saturn's magnetosphere and magnetic field and found its planet-size moon, Titan, to be too cold for life. Hurtling underneath the ring plane, the probe sent back pictures of Saturn's rings. The rings, which normally seem bright when observed from Earth, appeared dark in the Pioneer pictures, and the dark gaps in the rings seen from Earth appeared as bright rings.

Pioneer 11 image of Saturn taken on 1979/08/26

Pioneer 11 image of Saturn taken on 1979/08/26 Pioneer 11 image of Saturn taken on 1979/09/01

Pioneer 11 image of Saturn taken on 1979/09/01 Pioneer 11 image of Saturn taken on 1979/09/01

Pioneer 11 image of Saturn taken on 1979/09/01 Outgoing Pioneer 11 image of Saturn taken on 1979/09/03

Outgoing Pioneer 11 image of Saturn taken on 1979/09/03 Pioneer 11 image of Saturn's moon Titan

Pioneer 11 image of Saturn's moon Titan

Interstellar mission

On February 25, 1990, Pioneer 11 became the 4th man-made object to pass beyond the orbit of the planets.[29]

NASA ends operations

By 1995, Pioneer 11 could no longer power any of its detectors, so the decision was made to shut it down.[30] On September 29, 1995, NASA's Ames Research Center, responsible for managing the project, issued a press release that began, "After nearly 22 years of exploration out to the farthest reaches of the Solar System, one of the most durable and productive space missions in history will come to a close." It indicated NASA would use its Deep Space Network antennas to listen "once or twice a month" for the spacecraft's signal, until "some time in late 1996" when "its transmitter will fall silent altogether." NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin characterized Pioneer 11 as "the little spacecraft that could, a venerable explorer that has taught us a great deal about the Solar System and, in the end, about our own innate drive to learn. Pioneer 11 is what NASA is all about – exploration beyond the frontier."[31] Besides announcing the end of operations, the dispatch provided a historical list of Pioneer 11 mission achievements.

NASA terminated routine contact with the spacecraft on September 30, 1995, but continued to make contact for about 2 hours every 2 to 4 weeks.[30] Scientists received a few minutes of good engineering data on November 24, 1995, but then lost final contact once Earth moved out of view of the spacecraft's antenna.[4][32]

Timeline

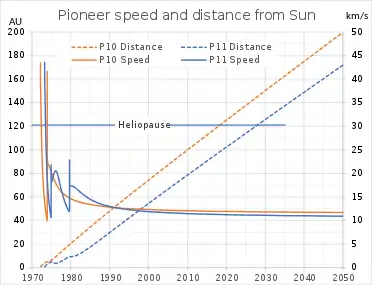

Plot 1 is viewed from the north ecliptic pole, to scale.

Plots 2 to 4 are third-angle projections at 20% scale.

In the SVG file, hover over a trajectory or orbit to highlight it and its associated launches and flybys.

| Timeline of travel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Current status

As of January 20, 2023, Pioneer 11 is estimated to be 111.678 AU (1.67068×1010 km; 1.03811×1010 mi) from the Earth and 110.764 AU (1.65701×1010 km; 1.02962×1010 mi) from the Sun; and traveling at 11.176 km/s (40,230 km/h; 25,000 mph) (relative to the Sun) and traveling outward at about 2.36 AU per year.[34][35] The spacecraft is heading in the direction of the constellation Scutum near the current position (January 2023) RA 18h 54m dec -8° 59' (J2000.0), close to Messier 26. In 928,000 years, it will pass within 0.25pc of the K dwarf TYC 992-192-1,[36] and will pass near the star Lambda Aquilae in about four million years.[37]

Pioneer 11 has now been overtaken by the two Voyager probes launched in 1977, and Voyager 1 became the most distant object built by humans and will remain so for the foreseeable future, as no probe launched since Voyager has the speed to overtake it. [38]

Pioneer anomaly

Analysis of the radio tracking data from the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft at distances between 20 and 70 AU from the Sun had consistently indicated the presence of a small but anomalous Doppler frequency drift. The drift can be interpreted as due to a constant acceleration of (8.74 ± 1.33) × 10−10 m/s2 directed towards the Sun. Although it was suspected that there was a systematic origin to the effect, none was found. As a result, there has been sustained interest in the nature of this so-called "Pioneer anomaly".[39] Extended analysis of mission data by Slava Turyshev and colleagues determined the source of the anomaly to be asymmetric thermal radiation and the resulting thermal recoil force acting on the face of the Pioneers away from the Sun,[40] and in July 2012 the group of researchers published their results in the Physical Review Letters scientific journal.[41]

Pioneer plaque

Pioneer 10 and 11 both carry a gold-anodized aluminum plaque in the event that either spacecraft is ever found by intelligent lifeforms from other planetary systems. The plaques feature the nude figures of a human male and female along with several symbols that are designed to provide information about the origin of the spacecraft.[42]

Commemoration

In 1991, Pioneer 11 was honored on one of 10 United States Postage Service stamps commemorating uncrewed spacecraft exploring each of the then nine planets and the Moon. Pioneer 11 was the spacecraft featured with Jupiter. Pluto was listed as "Not yet explored".[43]

Gallery

Pioneer 11 and Saturn rings on September 1, 1979 (artist concept)

Pioneer 11 and Saturn rings on September 1, 1979 (artist concept) Pioneer 11's flyby of Saturn (artist concept)

Pioneer 11's flyby of Saturn (artist concept)

See also

References

- "Pioneer 11". NASA's Solar System Exploration website. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- Fimmel, R. O.; Swindell, W.; Burgess, E. Pioneer Odyssey. SP-349/396. Washington, D.C.: NASA-Ames Research Center. OCLC 3211441. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- "The Pioneer Missions". Nasa.gov. March 3, 2015.

- "Pioneer 11: In Depth". Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- Mark, Hans: Pioneer Odyssey SP-349/396, Chapter 5, NASA-Ames Research Center, 1974

- "The Pioneer Missions". Nasa.gov. March 3, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- "Milestones of Flight". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- William E. Burrows, Exploring Space, (New York: Random House, 1990)

- Wade, Mark. "Pioneer 10-11". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- "Weebau Spaceflight Encyclopedia". Weebau.com. November 9, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- "Pioneer 10 & 11". solarviews.com. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- "Magnetic Fields". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Quadrispherical Plasma Analyzer". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- Simpson 2001, p. 146.

- "Charged Particle Instrument (CPI)". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Cosmic-Ray Spectra". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Geiger Tube Telescope (GTT)". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Jovian Trapped Radiation". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Meteoroid Detectors". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Asteroid/Meteoroid Astronomy". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Ultraviolet Photometry". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Imaging Photopolarimeter (IPP)". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Infrared Radiometers". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Jovian Magnetic Field". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- "Image : Viewed down from north ecliptic pole" (JPG). Nasa.gov. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- "Pioneer 11 Successfully Retargeted for Saturn". New Scientist. May 9, 1974. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- "In Depth | Pioneer 11". NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- "Pioneer 11 Mission Information". Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- "Pioneer 11 Is Reported to Leave Solar System". Nytimes.ocm. February 25, 1990. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- "Farewell to a Pioneer". Science News. October 14, 1995.

- "Pioneer 11 to End Operations after Epic Career". NASA / Ames Research Center. September 29, 1995. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- Howell, Elizabeth (September 26, 2012). "Pioneer 11: Up Close with Jupiter & Saturn". Space.com. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- Muller, Daniel. "Pioneer 11 Full Mission Timeline". Daniel Muller. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- "Spacecraft escaping the Solar System". Heavens-Above.com. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- "Sky Map - Pioneer 11". Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- Bailer-Jones, Coryn A. L.; Farnocchia, Davide (April 3, 2019). "Future stellar flybys of the Voyager and Pioneer spacecraft". Research Notes of the AAS. 3 (4): 59. arXiv:1912.03503. Bibcode:2019RNAAS...3...59B. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab158e. S2CID 134524048.

- "Hardware, Leaving the Solar System: Where are they now?", DK Eyewitness Space Encyclopedia

- "Voyager - Mission Status". Voyager.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- Britt, Robert Roy (October 18, 2004). "The Problem with Gravity: New Mission Would Probe Strange Puzzle". Space.com. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

The discrepancy caused by the anomaly amounts to about 248,500 miles (399,900 kilometres), or roughly the distance between Earth and the Moon. That's how much farther the probes should have traveled in their 34 years, if our understanding of gravity is correct.

- "Pioneer Anomaly Solved!". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on April 22, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- Support for the thermal origin of the Pioneer anomaly Archived January 13, 2013, at archive.today, Slava G. Turyshev et al., Physical Review Letters, accepted April 11, 2012, accessed July 19, 2012

- Carl Sagan; Linda Salzman Sagan & Frank Drake (February 25, 1972). "A Message from Earth". Science. 175 (4024): 881–884. Bibcode:1972Sci...175..881S. doi:10.1126/science.175.4024.881. PMID 17781060. Paper on the background of the plaque. Pages available online: 1 Archived February 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, 2 Archived February 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, 3 Archived February 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, 4 Archived February 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Kronish, Syd (October 27, 1991). "Space Launches are Featured". Newspapers.com. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

Sources

- Simpson, J. A. (2001). "The cosmic radiation". In Johan A. M. Bleeker; Johannes Geiss; Martin C. E. Huber (eds.). The century of space science. Vol. 1. Springer. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-7923-7196-0.

External links

- Pioneer Project Home Page

- Pioneer 11 Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Ted Stryk's Pioneer 11 at Saturn page

- NSSDC Pioneer 11 page

- Pioneer Odyssey, NASA SP-396, 1977 - This is an entire book about the Pioneer 10 with all pictures and diagrams, on-line. Scroll down to click on the "Table of Contents" link.

- Pioneer: First to Jupiter, Saturn, and beyond, Richard O. Fimmel, NASA SP-446, 1980, about the Pioneer project but especially about the Pioneer 11 mission.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)