History of rail transportation in California

The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines securely linked California to the rest of the country, and the far-reaching transportation systems that grew out of them during the century that followed contributed to the state's social, political, and economic development. When California was admitted as a state to the United States in 1850, and for nearly two decades thereafter, it was in many ways isolated, an outpost on the Pacific, until the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869.

| History of California |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

| Regions |

| Bibliographies |

|

|

Passenger rail transportation declined in the early- and mid-20th Century with the rise of the state's car culture and road system. It has since undergone something of a renaissance, with the introduction of services such as Metrolink, Coaster, Caltrain, Amtrak California, and others. On November 4, 2008, the People of California passed Proposition 1A, which helped provide financing for a high-speed rail line.

19th century

Background

The early Forty-Niners of the California Gold Rush wishing to come to California were faced with limited options. From the East Coast, for example, a sailing voyage around the tip of South America would take five to eight months,[1] and cover some 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 km). An alternative route was to sail to the Atlantic side of the Isthmus of Panama, to take canoes and mules for a week through the jungle, and then on the Pacific side, to wait for a ship sailing for San Francisco.[2] During the 1850s the voy:Ruta de Transito through Nicaragua was another option. Eventually, most gold-seekers took the overland route across the continental United States, particularly along the California Trail.[3] Each of these routes had its own deadly hazards, from typhoid fever to cholera or Indian attack.[4][5]

Transcontinental links

The very first "inter-oceanic" railroad that affected California was built in 1855 across the Isthmus of Panama, the Panama Railway.[6][7] The Panama Railway reduced the time needed to cross the Isthmus from a week of difficult and dangerous travel to a day of relative comfort. The building of the Panama Railroad, in combination with the increasing use of steamships (instead of sailing ships) meant that travel to and from California via Panama was the primary method used by people who could afford to do so, and was used for valuable cargo, such as the gold being shipped from California to the East Coast.[8]

California's symbolic and tangible connection to the rest of the country was fused at Promontory Summit, Utah, as the "last spike" was driven to join the tracks of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads, thereby completing the first transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869 (before that time, only a few local rail lines operated in the State, the first being the Sacramento Valley Railroad).[9] The 1,600 mile (2,575-kilometer) trip from Omaha, Nebraska, would now take mere days. The Wild West was quickly transformed from a lawless, agrarian frontier to what would become an urbanized, industrialized economic and political powerhouse. Of perhaps greater significance is the unbridled economic growth that was spurred on by the sheer diversity of opportunities available in the region.

The four years following the Golden Spike ceremony saw the length of track in the U.S. double to over 70,000 miles (nearly 113,000 kilometers).[10] By around the start of the 20th century, the completion of four subsequent transcontinental routes in the United States and one in Canada would provide not only additional pathways to the Pacific Ocean, but would forge ties to all of the economically important areas between the coasts as well. Virtually the entire country was accessible by rail, making a national economy possible for the first time. And while federal financial assistance (in the form of land grants and guaranteed low-interest loans, a well-established government policy) was vital to the railroads' expansion across North America, this support accounted for less than eight percent (8%) of the total length of rails laid; private investment was responsible for the vast majority of railroad construction.[11]

As rail lines pushed further and further into the wilderness, they opened up huge areas. The railroads helped establish towns and settlements, paved the way to abundant mineral deposits and fertile tracts of pastures and farmland, and created new markets for eastern goods. It is estimated that by the end of World War II, rail companies nationwide remunerated to the government over $1 billion dollars, more than eight times the original value of the lands granted.[12] The principal commodity transported across the rails to California was people: by reducing the cross-country travel time to as little as six days, men with westward ambitions were no longer forced to leave their families behind. The railroads would, in time, provide equally important linkages to move the inhabitants throughout the state, interconnecting its blossoming communities.

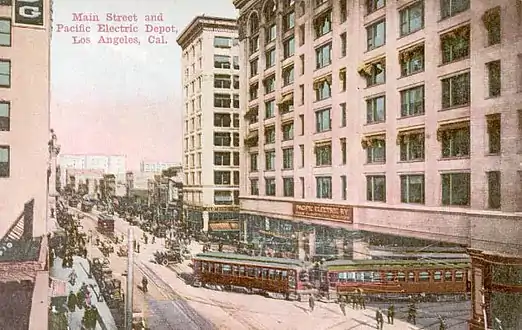

"Transportation determines the flow of population," declared J. D. Spreckels, one of California's early railroad entrepreneurs, just after the dawn of the twentieth century. "Before you can hope to get people to live anywhere...you must first of all show them that they can get there quickly, comfortably and, above all, cheaply."[13] Among Spreckels' many accomplishments was the formation of the San Diego Electric Railway in 1892, which radiated out from downtown to points north, south, and east and helped urbanize San Diego. Henry Huntington, the nephew of Central Pacific founder Collis P. Huntington, would develop his Pacific Electric Railway in Los Angeles and Orange Counties with much the same result. Spreckels' greatest challenge would be to provide San Diego with its own direct transcontinental rail link in the form of the San Diego and Arizona Railway (completed in November 1919), a feat that nearly cost the sugar heir his life.[14] The Central Pacific Railroad, in effect, initiated the trend by offering settlement incentives in the form of low fares, and by placing sections of its government-granted lands up for sale to pioneers.

When the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad charted its own solo course across the continent in 1885 it chose Los Angeles as its western terminus, and in doing so fractured the Southern Pacific Railroad's near total monopoly on rail transportation within the state. The original purpose of this new line was to augment the route to San Diego, established three years prior as part of a joint venture with the California Southern Railroad, but the Santa Fe would subsequently be forced to all but abandon these inland tracks through the Temecula Canyon (due to constant washouts) and construct its Surf Line along the coast to maintain its exclusive ties to Los Angeles.[15] Santa Fe's entry into Southern California resulted in widespread economic growth and ignited a fervent rate war with the Southern Pacific, or "Espee" as the road was often referred to; it also led to Los Angeles' well-documented real estate "Boom of the Eighties".[16] The Santa Fe Route led the way in passenger rate reductions (often referred to as "colonist fares") by, within a period of five months, lowering the price of a ticket from Kansas City, Missouri to Los Angeles from $125 to $15, and, on March 6, 1887 to a single dollar.[17] The Southern Pacific soon followed suit and the level of real estate speculation reached a new high, with "boom towns" springing up literally overnight. Free, daily railroad-sponsored excursions (complete with lunch and live entertainment) enticed overeager potential buyers to visit the many undeveloped properties firsthand and invest in the land.

As with the Comstock mining securities boom of the 1870s, Los Angeles' land boom attracted an unscrupulous element that often sold interest in properties whose titles were not properly recorded, or in tracts that did not even exist.[18] Major advertising campaigns by the SP, Santa Fe, Union Pacific, and other major carriers of the day not only helped transform southern California into a major tourist attraction but generated intense interest in exploiting the area's agricultural potential.[19] Word of the abundant work opportunities, high wages, and the temperate and healthful California climate spread throughout the Midwestern United States, and led to an exodus from such states as Iowa, Indiana, and Kansas; although the real estate bubble "burst" in 1889 and most investors lost their all, the Southern California landscape was forever transformed by the many towns, farms, and citrus groves left in the wake of this event.[17]

Historians James Rawls and Walton Bean have speculated that were it not for the discovery of gold in 1848, Oregon might have been granted statehood ahead of California, and therefore the first Pacific Railroad might have been built to that state, or at least been born to a more benevolent group of founding fathers.[20] This speculation lacks support, however, when one considers that a significant hide and tallow trade between California and the eastern seaports was already well-established, that the federal government had long planned for the acquisition of San Francisco Bay as a western port, and that suspicions regarding England's intentions towards potentially extending their holdings in the region southward into California would almost certainly have forced the government to embark on the same course of action.

While the completion of the first transcontinental railroad was a major milestone in America's history, it would also foster the birth of a railroad empire that would have a dominant influence over California's evolution for years to come. Despite all of the shortcomings, in the end the State gained unprecedented benefits from its associations with the railroad companies.

Agriculture

Even today, California is well known for the abundance and many varieties of fruit trees that are cultivated throughout the state. The only fruits indigenous to the region, however, consisted of wild berries or grew on small bushes. Spanish missionaries brought fruit seeds over from Europe, many of which had been introduced to the Old World from Asia following earlier expeditions to the continent; orange, grape, apple, peach, pear, and fig seeds were among the most prolific of the imports.

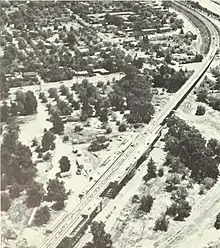

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, fourth in the Alta California chain, was founded in 1771 near what would one day be the City of Los Angeles.[21] Thirty-three years later the mission would unknowingly witness the origin of the California citrus industry with the planting of the region's first significant orchard, though the commercial potential of citrus would not be realized until 1841.[22] Several small carloads of California crops were shipped eastward via the new transcontinental route almost immediately after its completion, using a special type of ventilated boxcar modified specifically for this purpose. The advent of the iced refrigerator car or "reefer" led to increases in both the amount of product carried and in the distances traveled.

For years, the overall scarcity of oranges in particular led to the general perception that they were suitable only for holiday table decoration or as indulgences for the affluent. During the 1870s, however, hybridization of California oranges led to the creation of several flavorful strains, chief among these the Navel and Valencia varieties, whose development allowed for year-round cultivation of the fruit. Substantial foreign (out-of-state) markets for California citrus would come into full stature by 1890, initiating a period referred to as the Orange Era.[23]

As the market for agricultural goods outside the state's boundaries increased, the Santa Fe developed a massive fleet of refrigerator dispatch cars, and in 1906 the Southern Pacific joined with the Union Pacific Railroad to create the Pacific Fruit Express.[24] Fully half the farm products produced in California could now be exported throughout the country, with western railroads carrying virtually all of the perishable fruit traffic.[25] The western states of California, Arizona, and Oregon would dominate U.S. agricultural production by the coming of the Great Depression; once such diverse and high-demand crops as wheat, sugar beets, olives, and lettuce were cultivated, California would become known as the nation's "produce basket."[26]

Oil boom

With the expansion of agriculture interests throughout the state (along with new rail lines to carry the goods to faraway markets), new communities were founded and existing towns expanded. Agrarian successes led to the establishment of post offices, schools, churches, mercantile outlets, and ancillary industries such as packing houses. The discovery of brea, more commonly referred to as tar, in Southern California would lead to an oil boom in the early twentieth century. Railroad companies soon discovered that shipping wooden barrels loaded with oil via boxcars was not cost-effective, and developed steel cylindrical tank cars capable of transporting bulk liquids virtually anywhere. By 1915, the transportation of petroleum products had become a lucrative endeavor for western railroads.[27]

Most oil tank cars would remain in revenue service for decades until the "Black Bonanza" had run its course. The Southern Pacific is credited with being the first western railroad to experiment in 1879 with the use of oil in its locomotives as a fuel source in lieu of coal (with substantial technical assistance from the Union Oil Company, one of the SP's biggest accounts).[28] By 1895, oil-burning locomotives were in operation on a number of Southern Pacific routes, and on the competing California Southern and Great Northern Railway as well.[29] This innovation not only allowed the SP (and other railroads that soon followed their example) to benefit from the use of this abundant and economically viable fuel source, but to create new markets by capitalizing on the burgeoning petroleum industry. The conversion from coal to oil also help solved the Southern Pacific's problem of intense smoke in the tunnels of the Sierra Nevada. Thanks to the railroads, California was once again thrust into the limelight.

Tourism

The railroads were among the first to promote California tourism as early as the 1870s, both as a means to increase ridership and to create new markets for the freight hauling business in the areas they served.[30] Some sixty years later, the Santa Fe would lead a resurgence in leisure travel to and along the west coast aboard such "name" trains as the Chief and later the Super Chief; the Southern Pacific would soon follow suit with their Golden State and Overland Flyer trains, and the Union Pacific with its City of Los Angeles and City of San Francisco. The immense popularity of Helen Hunt Jackson's 1884 novel Ramona in particular fueled a surge in tourism, which happened to coincide with the opening of SP's Southern California lines.[31]

The Santa Fé embraced the aura of the American Southwest in its advertising campaigns as well as its operations. The AT&SF routes and the high level of service provided thereon became popular with stars of the film industry in the thirties, forties and fifties, both building on and adding to the Hollywood mystique. The "golden age" of railroading would eventually end as travel by automobile and airplane became more cost-effective, and popular.

Corruption and scandal

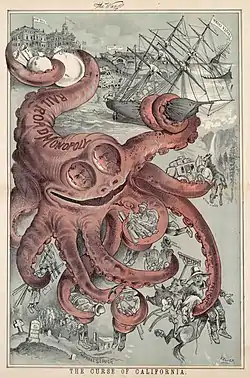

In 1901, Frank Norris vilified the Southern Pacific for its monopolistic practices in his acclaimed novel The Octopus: A Story of California; John Moody's 1919 work The Railroad Builders: A Chronicle of the Welding of the State referred to "the American railroad problem" wherein the men who rode the iron horse were characterized as "monsters" that too often suppressed government reform and economic growth through political chicanery and corrupt business practices.[32]

While it is true that much of the traveling public would have been unable to make the trip to California's sunny climate were it not for the fleet, relatively safe, and affordable trains of the western railroads, it is also true that those companies in effect preyed on those same settlers once they arrived at the end of the line. For instance, while the railroads provided much-needed transportation routes to out-of-state markets for locally produced raw materials and avenues of the import for eastern goods, there were numerous instances of rate fixing schemes among the various carriers, the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific included.[33] Opposition to the railroads began early in Southern California's history due to the questionable practices of The Big Four in conducting the business of the Central (later Southern) Pacific. The Central Pacific Railroad (and later the Southern Pacific) maintained and operated whole fleets of ferry boats that connected Oakland with San Francisco by water. Early on, the Central Pacific gained control of the existing ferry lines for the purpose of linking the northern rail lines with those from the south and east; during the late 1860s the company purchased nearly every bayside plot in Oakland, creating what author and historian Oscar Lewis described as a "wall around the waterfront" that put the town's fate squarely in the hands of the corporation.[34] Competitors for ferry passengers or dock space were ruthlessly run out of business, and not even stage coach lines could escape the group's notice, or wrath.

The Northern California railroad barons also effectively slowed San Diego's development in the early 20th century. San Diego had a natural harbor and many thought that it would become a major port on the west coast. However, San Francisco was strongly opposed to this as San Diego's development would hurt their trade. Charles Crocker, the manager of Central Pacific Railroad was quoted as saying: “I would not take the road to San Diego as a gift. We would blot San Diego out of existence if we could, but as we can[']t do that we shall keep it back as long as we can.” Instead, the Central Pacific only extended their rail route into Los Angeles."

Competition between carriers for rail routes was fierce as well, and unscrupulous means were often used to gain any advantage over one another. Santa Fe work crews engaged in sabotage to slow the progress of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad through the Rockies as the two fought their way toward the Coast; the Santa Fe (in conjunction with the California Southern) would win the race in establishing its connection to Bakersfield in 1883. Some eleven years earlier, the Southern Pacific essentially blackmailed the then-fledgling City of Los Angeles into paying a hefty subsidy to ensure that the railroad’s north-south line would pass through town; in 1878, the company would be rebuffed in its attempts to extend its Anaheim branch southward to San Diego through Orange County's Irvine Ranch without securing the permission of James Irvine Sr., a longtime rival of Collis Huntington.[35] The Southern Pacific would similarly block the westward progress of the Santa Fe (known to some as the People's Railroad) until September 1882, when a group of enraged citizens ultimately forced the railroad's management to relent.[36] Numerous accounts of similar "frog wars" and other such tactics have been recorded throughout California's railroad history.

Perhaps the most notorious examples of impropriety on the part of the railroads surround the process of land acquisition and sales. Since the federal government granted to the companies alternate tracts of land that ran along the tracks they had laid, it was generally assumed that the land would in turn be sold at its fair market value at the time the land was subdivided; circulars distributed by the SP (which was at the time a holding company formed by the Central Pacific Railroad) certainly implied as much. However, at least some of the tracts were put on the market only after considerable time had passed, and the land improved well beyond its raw state.[37]

Families faced with asking prices of ten times or more of the initial value more often than not had no choice but to vacate their homes and farms, in the process losing everything they worked for; often it turned out to be a railroad employee who had purchased the property in question. A group of immigrant San Joaquin Valley farmers formed the Settlers' League in order to challenge the Southern Pacific's actions in court, but after all of the lawsuits were decided in the favor of the railroads, one group decided to take matters into their own hands. What resulted was the infamous Battle at Mussel Slough, in which armed settlers clashed with railroad employees and law enforcement officers engaged in eviction proceedings. Six people were killed in the ensuing gunfight.[38] The Southern Pacific would emerge from the tragedy as the prime target of journalists such as William Randolph Hearst, ambitious politicians, and crusade groups for decades to follow.[39] Leland Stanford's term as Governor of California (while serving as president of Central Pacific Railroad and later Southern Pacific) enhanced the corporation's political clout, but simultaneously further increased its notoriety as well.

Regulation

Public response to the corruption that arose from California's economic "explosion" led to the enactment of numerous reform and regulation measures, many of which coincided with the ascendancy of the Populist and Progressive movements. Early examples of railroad regulation include Granger case decisions in the 1870s, and the creation of the first (albeit ineffective) Railroad Commission via amendment of the State's Constitution of 1879, forerunner of today's California Public Utilities Commission. In 1886, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Santa Clara County in Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad. The documents of the Court decision included a statement that a corporation henceforth could be considered an American citizen, with all the associated immunities and privileges (except the right to vote). The document phrasing has long made it difficult for states to pass legislation that could make corporations accountable to the people. The Stetson-Eshelman Act of 1911 provided for the fixing of shipping rates by state legislatures. In 1911, California's new Progressive government established the second Railroad Commission, more effective and less corrupted than the first one.[40]

20th century

Buses replace streetcars and interurbans

_(5448636059).png.webp)

Passenger rail in California during the early 20th Century was dominated by private companies. Interurban railways gained popularity in the early part of the century as a means of medium-distance travel, usually as components of real estate speculation schemes. The Pacific Electric Railway Company Red Car Lines was the largest electric railway system in the world by the 1920s, with over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of tracks and 2,160 daily services across Los Angeles and Orange Counties.[41] The Sacramento Northern Railway operated the world's longest single electric interurban service between Oakland and Chico. These and other services were largely abandoned in the 1940s and 50s as ridership declined and equipment fell into disrepair.

Local services were mostly controlled by a few primary operators. The San Diego Electric Railway, founded by John D. Spreckels in 1892, was the major transit system in the San Diego area during that period. In the Los Angeles area, real estate tycoon Henry Huntington established both the Los Angeles Railway, also known as the Yellow Car system, and the above-mentioned Pacific Electric Red Car System in 1901. The San Francisco Municipal Railway was established in 1912. Business magnate Francis Marion Smith then created the Key System in 1903 to connect San Francisco with the East Bay. The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge opened to rail traffic in 1939 only to have the last trains run in 1958 after fewer than twenty years of service – the tracks were torn up and replaced with additional lanes for automobiles. All four streetcar systems, and other similar rail networks across the state, declined in the 1940s with the rise of California's car culture and freeway network. They were then all eventually taken over to some degree, and dismantled, in favor of bus service by National City Lines, a controversial national front company owned by General Motors and other companies in what became known as the General Motors streetcar conspiracy. San Francisco's city-owned lines were not privatized, but were still largely converted to bus and trolleybuses.

Modern light rail and subway systems

One urban system that survived the streetcar decline was the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni) in San Francisco. Its five heavily used streetcar lines traveled for at least part of their routes through tunnels or otherwise reserved right-of-way, and thus could not be converted to bus lines.[42] As a result, these lines, running PCC streetcars, continued in operation for several decades. When plans for stations in the double-decker Market Street subway tunnel through downtown San Francisco, with BART on the lower level and MUNI on the upper level, required high platforms, it meant that the PCCs could not be used in them. Hence, MUNI ordered a fleet of new light rail vehicles, and Muni Metro began service in 1980. The San Francisco cable car system came under full Municipal ownership in 1952, and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966 after almost being replaced entirely by buses in the previous decades. The system had fallen into disrepair by the 70s and a massive overhaul of the system resulted in the lines current configuration opening in 1984.

Planning for a modern, urban rapid transit system in California did not begin until the 1950s, when California's legislature created a commission to study the Bay Area's long-term transportation needs. Based on the commission's report, the state legislature created the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) District in 1957 to build a rapid transit system to replace the Key System and provide region-wide rail connectivity. Initially intended to include all nine counties that ring the San Francisco Bay, the final system would feature service between San Francisco and three branches in the East Bay, serving three counties total. Passenger service on BART then began in 1972, but expansion to the system was planned almost immediately.

Environmental and traffic concerns beginning in the 1970s led to a resurgence in urban passenger rail, specifically the construction light rail networks. Hurricane Kathleen in 1976 damaged the San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway Desert Line to San Diego, and the San Diego portion became an isolated railway. After prior decades of grappling with the option of building rapid transit BART-like line, light rail was eventually chosen as a more cost-effective solution. The San Diego Trolley opened in 1981 partially as a means to preserve freight service on this line, but is widely considered the system that lead to renewal in the concept of urban passenger rail. This system was followed in California by both the Sacramento Regional Transit Light Rail and Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority light rail systems in 1987, as well as more nationwide.

The development of the mixed-mode Los Angeles Metro Rail began as two separate undertakings. The Southern California Rapid Transit District was planning a new subway along Wilshire Boulevard while the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission was also designing a light rail system utilizing a former Pacific Electric corridor. The light rail Blue Line opened to Long Beach in 1990. The Red rapid transit line began construction in 1986, and its first segment opened in 1993, the year both entities were merged. Expansion of the system was initially hampered by compromises and prohibiting legislation, but the light rail Green Line opened in 1995, followed by the Red Line's extension to Wilshire/Western in Koreatown (which received its own designation as the Purple Line in 2006).

Amtrak era

When Amtrak assumed operation of passenger rail services in the United States in 1971, most long-haul and commuter trains ceased operation. New lines were either based on previous routings or extended from old services. Service to Denver was provided via the San Francisco Zephyr (on a route largely retained from the City of San Francisco), and extended through to Chicago in 1983 with the California Zephyr. Los Angeles services have remained largely unchanged since the corporation's inception. The Southwest Chief is the successor to the ATSF Super Chief, still running from Chicago. The Sunset Limited to New Orleans is the oldest maintained named train service in the United States, inherited from the Southern Pacific service running since 1894. The Texas Eagle is a direct successor to the Missouri Pacific train of the same name. No one passenger train ran the length of the west coast before 1971. Coast Starlight service was initiated as a thrice weekly service from Seattle to San Diego, later expanded to run daily but cut back to Los Angeles by 1972. Services to Las Vegas, Nevada were provided by the weekend-only Las Vegas Limited in 1976 and long-distance Desert Wind, which operated between 1979 and 1997.

Caltrans and Amtrak partnered together to form Amtrak California in 1976. The Pacific Surfliner, serving the coastal communities of Southern California between San Diego and San Luis Obispo, is an extension of the historical San Diegan that was previously operated by ATSF and continued service under Amtrak – it is the busiest corridor outside of the Northeast. Amtrak's formation left the San Joaquin Valley without rail service, but this was rectified in 1974 with the initiation of San Joaquins service. At first serving Bakersfield to Oakland, additional services were added north to Sacramento in 1999. Capitol Corridor service began as simply Capitols in 1991 and connects the Bay Area with the Sacramento area, acting closer to true commuter rail than most other Amtrak routes. The Spirit of California was a short-haul sleeper service that ran between Los Angeles and Sacramento via the Coast Starlight routing. The train lasted under two years from 1981 to 1983. The Amtrak California branding is being deprecated as the three California-based lines have transitioned to control under local joint powers authorities.

One exception

The California Western Railroad is a short line railroad that never joined Amtrak. For most of its existence, the line served to haul lumber from the Mendocino Coast Range to the Northwestern Pacific Railroad in Willits. The company also ran one daily round trip passenger service to Fort Bragg — the Skunk Train.[43] By 1996, freight shipments had declined to the point that passenger excursions became the railroad's primary source of income. A series of tunnel collapses starting in 2013 severed the line, and service was thence reduced to purely excursions without through running.[44]

Commuter rail

.jpg.webp)

One service spared from discontinuance was the Southern Pacific Peninsula Commute, operational in some form since 1863. The railroad had long petitioned the California Public Utilities Commission to end the service, but remained subsidized by the state. Caltrans renamed it Caltrain in 1987. The overseeing joint powers authority acquired the line in 1991, and eventually took over responsibility for operating the service. By 1988, it was the only commuter rail being operated in the state.[45]

An attempt to start commuter rail service in Los Angeles was undertaken in 1982, although CalTrain service would last fewer than six months. Amtrak initiated Orange County Commuter service in 1990 under the San Diegans brand, but a more regional approach was deemed necessary. Southern Pacific sold 175 miles (282 km) of track to the newly formed Southern California Regional Rail Authority in 1991, which became the nucleus of the Metrolink commuter rail network when it opened one year later.[46][47] The system would consist of six lines by the end of the millennium, including assumed operation of the Orange County service.

The North San Diego County Transit Development Board was created in 1975 to consolidate and improve transit in northern San Diego County. Planning began for a San Diego–Oceanside commuter rail line, then called Coast Express Rail, in 1982.[48] The Board established the San Diego Northern Railway Corporation (SDNR) — a nonprofit operating subsidiary — in 1994,[48] and purchased the 41 miles (66 km) of the Surf Line within San Diego County plus the 22-mile (35 km) Escondido Branch from the Santa Fe Railway that year.

By the 90s, growth in the Tri-Valley and the middle Central Valley had led to congestion on local freeways while providing little access to public transit. In May 1997, the Altamont Commuter Express Joint Powers Authority was formed by the San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission, Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, and Alameda Congestion Management Agency with the intent to establish commuter rail service over the Altamont Pass and Niles Canyon. The Altamont Commuter Express, connecting San Joaquin County and the Bay Area, then began operations in 1998.

Freight

Railways companies, and thus routes, were largely consolidated under a few Class I railroads by the end of the century. In 1982, the Union Pacific Corporation purchased the Western Pacific and the WP became part of a combined Union Pacific rail system: the Union Pacific Railroad, the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and the Western Pacific.[49] Southern Pacific was purchased by Union Pacific and acquisition was finalized in 1996. In the same year, the ATSF merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad to form BNSF Railway. With those two mergers, the two major railroads in California became Union Pacific and BNSF, with some smaller short line and switching operations. Line abandonment has generally increased since then, as redundancies are reduced. The Union Pacific line over Tehachapi Pass operates as one of the busiest single-track railways in the world. The line through the pass features the Tehachapi Loop, a landmark 3,779 feet (0.72 mi; 1.15 km) long single-track spiral that rises at a steady two-percent grade, and gains 77 feet (23 m) in elevation.[50] Because of the traffic, Amtrak passenger services are normally banned from using the loop.[51]

21st century

Railway expansion

Rail systems saw initial expansion in the first decades of the century. San Diego Trolley's Green Line began service in 2005, and Silver Line heritage streetcar service began limited service in 2011 with refurbished PCC's. The Sacramento RT Light Rail extended all of its lines including one linking Folsom to the Sacramento Amtrak station, the Blue Line extension project which provided transit to several colleges in the southwest part of the city, and the line to the River District. VTA light rail also saw expansion to San Jose Diridon station and Winchester, as well as the Vasona extension. All of these systems would experience various reroutings of service as new extensions came on line.

Bay Area Rapid Transit has seen expansions beyond its original vision, such as the Silicon Valley BART extension, Oakland Airport Connector, and the East Contra Costa BART Extension. BART and Caltrain jointly opened Millbrae station in 2003. BART placed an order for a replacement fleet of train cars in 2012, with expected full delivery by 2022. The passage of Measure RR on November 8, 2016 gave BART the funds to undertake a massive rebuild of the system's aging infrastructure, effectively freezing expansion plans not already programmed. A result of the agency's decision to hold expansion plans into Livermore prompted the creation of the Tri-Valley-San Joaquin Valley Regional Rail Authority in 2017 – an agency tasked with establishing a public transit service between BART and ACE trains.

San Francisco's Muni Metro has expanded service via the sequential Third Street Light Rail Project and Central Subway (with plans for a third extension underway). The heritage streetcar service was extended to Fisherman's Wharf via constructing light rail infrastructure in place of the demolished Embarcadero Freeway, and the E Embarcadero streetcar service entered regular service in 2015 providing a link between the waterfront and Caltrain. City Supervisor Scott Wiener called for sustained subway construction throughout San Francisco.[52][53]

LA Metro Rail's aggressive expansion policy was adopted owing to increased funding availability primarily from Measure R in 2008 and Measure M in 2016 as well as dissatisfaction with increasing automotive traffic. The Gold Line opened in 2003 and has been extended several times via the Eastside Extension and the Gold Line Foothill Extension. The Expo Line opened in 2012 along the route of the former Santa Monica Air Line, was completed to Santa Monica in 2016, and hit ridership projections 13 years earlier than forecast.[54] The Regional Connector brought the isolated Gold line into the rest of the LACMTA light rail system to provide more flexible service patterns. A more direct airport connection will be provided upon completion of the K Line (known as the Crenshaw/LAX Line during construction). Several extensions of the D Line are planned to bring subway service along the Wilshire / Westwood corridor and will likely connect to the Crenshaw/LAX Line. Multiple preparations for the 2028 Summer Olympics are being made under the Twenty-eight by '28 initiative, including establishing a rail route over the Sepulveda Pass, the East San Fernando Valley Light Rail Transit Project, extending the C Line to South Bay, the West Santa Ana Branch Transit Corridor, the Inglewood Transit Connector, and the Eastside Transit Corridor extension of the L Line (to become part of the E Line.)

Diesel multiple unit services

Sprinter began diesel multiple unit (DMU) service in 2008, connecting cities in northern San Diego County. This service follows the 22-mile (35 km) Escondido Branch, which was acquired by the San Diego Northern Railway in 1992 and was later transferred to the North County Transit District. The passenger trains are not FRA-compliant for operation in association with freight trains and therefore freight operations on the route are not permitted during passenger operations. For this reason the American Public Transportation Association and some publications refer to this line as light rail, but it does not conform to the normal engineering specifications usually associated with that term.

Sonoma–Marin Area Rail Transit was created by state legislation in 2002 to reestablish passenger service along the Northwestern Pacific Railroad right-of-way, providing a 70-mile (110 km) route from Cloverdale to Larkspur Ferry Terminal with a planned 16 stations. After prolonged delays, preview service commenced on a truncated portion of the line on June 28, 2017. Construction is ongoing with plans to reach Cloverdale by 2027. Unlike trains operating the Sprinter service, SMART's Nippon Sharyo DMUs are each powered by one Cummins QSK19-R[55] diesel engine with hydraulic transmission and regenerative braking, and meet US EPA Tier 4 emission standards. Structurally each DMU is FRA Tier 1 compliant with crash energy management features, making it capable of operating on the same line with standard North American freight trains without the need of special waivers.

The aforementioned East Contra Costa BART Extension breaks from Bay Area Rapid Transit convention by using standard gauge rail (the main system uses a broad gauge), allowing for standard modern DMU trainsets to operate on the branch line. Plans originally called for trains to share right of way with pre-existing freight tracks in Eastern Contra Costa County. The freight track's owners eventually refused BART to lay tracks along its own lines, and the project was integrated into the median of an adjacent highway widening and given dedicated tracks. Its opening extended the BART system an additional 10.1 miles (16.3 km) with two new stations.

On October 24, 2022, Arrow opened, connecting the rest of the Metrolink system with Redlands, California. This service, sharing part of its route with the Metrolink San Bernardino Line. runs along lightly used ex-Santa Fe tracks and serves five stations along its 9-mile (14 km) route.

High-speed rail

The California High-Speed Rail Authority was created in 1996 by the state to implement an 800-mile (1,300 km) rail system. It would provide a TGV-style high-speed link between the state's four major metropolitan areas, and would allow travel between Los Angeles's Union Station and the San Francisco Transbay Transit Center in two and a half hours. In November 2008, voters approved Proposition 1A, a bond measure that allocated $9 billion to finance the project. In 2012, the California legislature and Governor Jerry Brown approved financing for an initial stage of construction for the project.[56] The High Speed Rail Authority estimates that the initial stages will not be completed until 2022. The groundbreaking ceremony was held on January 6, 2015, and construction continues as of May 2019 despite financial and political difficulties. As part of Governor Gavin Newsom's 2019 State of the State address, he declared, "Right now, there simply isn’t a path to get from Sacramento to San Diego."[57] Cost increases have plagued the buildout, and in May 2019 the FRA cancelled a $928.6 million grant awarded to the project.[58]

As part of this effort, and due to rising ridership of its own, Caltrain undertook a project to electrify their service corridor between San Jose and San Francisco; high-speed rail services are expected to share this corridor once service is extended to the Bay Area. In August 2016, Caltrain awarded a contract to produce the trainsets needed for running on the electrified line,[59] while an official groundbreaking ceremony was held on July 21, 2017 at Millbrae station.[60][61] Project funding in the amount of $600 million comes from Proposition 1A funds that authorized the construction of high-speed rail.[62]

Altamont Corridor Express and San Joaquins services are planned to be enhanced and expanded as part of the state's general rail plan. CAHSR was originally to run over the Altamont Pass for its service route between the Central Valley and Silicon Valley, but these plans were later changed. New ACE lines are being built progressively to Ceres by 2023 and later to Merced. Additional services to Sacramento along a lesser-used rail line are also expected to be implemented in 2023, known as Valley Rail. Trains are planned to run to Merced and act as a feeder service in the northern section of the high speed rail service area.[63]

Freight

By 2013, California's freight railroad system consisted of 5,295 route miles (8,521 km) moving 159.6 million short tons (144.8 Mt).[64]

Union Pacific Railroad completed a project in 2009 to allow double-stacked intermodal containers to be transported across Donner Summit, allowing for increased loads as well as train lengths.[65]

Programs to further increase freight capacity through the state involved grade separation of the most congested level diamond crossings on the network. Colton Crossing was rebuilt between 2011 and 2013 to elevate the Union Pacific tracks over those owned by BNSF.[66] Stockton Diamond is expected to see a similar treatment starting in 2023.[67]

New systems

The OC Streetcar is under construction as of 2019, and will reestablish a local service along a segment of the Pacific Electric West Santa Ana Branch rail line in Santa Ana and Garden Grove.

The LAX People Mover will connect the Los Angeles International Airport to a mass transit system for the first time when it opens in 2024.

BART rejected a plan to expand the system to Livermore in 2018. This prompted the creation of the Tri-Valley-San Joaquin Valley Regional Rail Authority, which was tasked with providing a direct rail connection between the San Joaquin Valley and the BART system. The line is expected to utilize a county-owned segment of the former Transcontinental Railroad right-of-way through Tracy and over Altamont Pass.[68] Vehicle for hire companies have gained market share from rail service.[69]

See also

Notes

- Brands, H. W. (2003). The age of gold: the California Gold Rush and the new American dream. New York: Anchor (reprint ed.). pp. 103–121.

- Brands, H. W. (2003), pp. 75-85. Another route across Nicaragua was developed in 1851; it was not as popular as the Panama option. (see Rawls, James J.; Orsi, Richard J., eds. (1999). A golden state: mining and economic development in Gold Rush California. California History Sesquicentennial Series, 2. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. pp. 252–253.)

- Rawls and Orsi, (1999) p. 5.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for riches; gold fever and the making of California. Oakland, California, Berkeley and Los Angeles: Oakland Museum of California and University of California Press. pp. 101, 107.

- Duke and Kistler, p. 9

- Otis, Fessenden Nott (M.D.). Isthmus of Panama: History of the Panama railroad; and of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1867 pp. 15-16; 50-56.

- The Panama Railroad: 1865, 1868 & 1871 Certificates of Stock; an 1855 Newspaper Report of its Opening; 1861 & 1913 Maps; Early Harper's Engravings; and 1861 Schedule of Regular, Special and "Steamer" Trains.

- One ill-fated journey, that of the S.S. Central America, ended in disaster as the ship sank in a hurricane off the coast of the Carolinas in 1857, with an estimated three tons of California gold aboard. (see Hill, Mary (1999). Gold: the California story. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. pp. 192–196.) Another notable ship wreck was the steamship Winfield Scott, bound to Panama from San Francisco, which crashed into Anacapa Island off the Southern California coast in December 1853. All hands and passengers were saved, along with the cargo of gold, but the ship was a total loss.

- Daniels, p. 53

- Daniels, p. 54

- Daniels, p. 55

- Robinson, p. 157

- Dodge, p. 18

- Hanft, p. 77

- Duke, p. 43

- Donaldson and Myers, p. 58

- Duke and Kistler, p. 32

- Beebe, p. 240

- Rawls and Bean, p. 207

- Rawls and Bean, p. 112

- Wright, p. 25

- Thompson, p. 341

- Thompson, p. 342

- Daniels, p. 94

- Duke, p. 403

- Thompson, p. 343

- Duke, p. 404

- Duke, p. 432

- Yenne, p. 53

- Duke and Kistler, p. 60

- Triem, Judith P.; Stone, Mitch. "Rancho Camulos: National Register of Historic Places Nomination" (significance). San Buenaventura Research Associates. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- Moody, p. 237

- Lewis, p. 366

- Lewis, p. 371

- Donaldson and Myers, p. 14

- Donaldson and Myers, p. 43

- Yenne, p. 31

- Daniels, p. 59

- Yenne, p. 74

- "PUC History & Structure". California Public Utilities Commission 2007-12-28. Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- Demoro, Harre W. (1986). California's Electric Railways. Glendale, California: Interurban Press. ISBN 978-0-916374-74-7.

- "This is Light Rail Transit" (PDF). Transportation Research Board. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- Rail Passenger Development Plan: 1984-89 Fiscal Years. Sacramento, CA: Division of Mass Transportation, Caltrans. 1984. OCLC 10983344.

- "Two Views: Another Big Skunk Train Tunnel Collapse". Anderson Valley Advertiser. 2015-04-15. Archived from the original on 2019-07-23. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- Rail Passenger Development Plan: 1988-93 Fiscal Years. Sacramento, CA: Division of Mass Transportation, Caltrans. 1988. OCLC 18113227.

- "Metrolink (Southern California)". ireference.ca. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- "Southern California Regional Rail Authority (SCRRA) - Metrolink (United States), URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEMS AND OPERATORS". Jane's Information Group. 2009. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2015.(subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- "NCTD: Past, Present and Future" (PDF). North County Transit District. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 25, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- Holsendolph, Ernest (14 September 1982). "3 railroads given approval by I.C.C. to merge in west". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- "Tehachapi Pass Railroad Line". asce.org. American Society of Civil Engineers. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- Christopher McFadden (February 11, 2017). "Going Round the Bend with the Tehachapi Loop".

- Goldberg, Ted (8 September 2015). "S.F. Supervisor Scott Wiener Unveils His Subway Dream". KQED. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Wiener, Scott (8 September 2015). "San Francisco needs to keep those new subways coming". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Carino, Meghan McCarty (13 July 2017). "Expo Line far exceeds ridership goals, but growth will be difficult to sustain". KPCC. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- "CUMMINS QSK19-R TO POWER NIPPON SHARYO DMU TRAIN DESIGNED FOR NEW TRANSIT ROUTES IN NORTH AMERICA". 2014-04-25. Retrieved 2014-08-11.

- Michael Martinez (July 19, 2012). "Governor signs law to make California home to nation's first truly high-speed rail". CNN. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- Sheehan, Tim (12 February 2019). "Newsom wants to see high-speed trains for Merced-Bakersfield, puts brakes on SF-LA vision". Fresno Bee. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- Morin, Rebecca (16 May 2019). "Trump administration cancels nearly $1 billion in funding for California high-speed rail". USA Today. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- Vantuono, William C. (16 August 2016). "For Caltrain, 16 KISSes from Stadler (but no FLIRTs)". Railway Age. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "Caltrain hosts groundbreaking for Electrification Project" (Press release). Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board. 21 July 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (21 July 2017). "Caltrain electrification project takes symbolic step forward". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- "Caltrain Modernization Program 4th Quarter FY 2016 Progress Report" (PDF). Caltrain. p. 13. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "2020 Business Plan" (PDF). SJJPA. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "2018 California State Rail Plan (Draft)" (PDF). CalTrans. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- "UP improves Donner Pass tunnels to bolster double-stack operations". Progressive Railroading. November 24, 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Colton Crossing grade separation completed". Railway Gazette. August 29, 2013.

- Goldeen, Joe (20 September 2020). "Feds chip in $20M for major Stockton railroad project". The Record. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- Baldassari, Erin (May 24, 2018). "BART rejects Livermore expansion; mayor vows rail connection". East Bay Times. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- Baldassari, Erin (27 November 2016). "BART's Oakland Airport Connector losing money; Uber, Lyft to blame?". The Mercury News.

References

- Bain, David Haward (1999). Empire Express: Building the first transcontinental railroad. Viking Press, New York, NY. ISBN 0-670-80889-X.

- Beebe, Lucius (1965). The Central Pacific & The Southern Pacific Railroads: Centennial Edition. Howell-North Books, Berkeley, CA.

- Brands, H. W. (2003). The age of gold: the California Gold Rush and the new American dream. New York: Anchor (reprint ed.). ISBN 0-385-72088-2.

- Daniels, Rudolph (2000). Across the continent: North American railroad history. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN. ISBN 0-253-21411-4.

- Dodge, Richard V. (1960). Rails of the Silver Gate: The Spreckels San Diego empire. Golden West Books, San Marino, CA. ISBN 0-87095-019-3.

- Donaldson, Stephen E.; William A. Myers (1990). Rails through the orange groves, Volume I. Trans-Anglo Books, Glendale, CA. ISBN 0-87046-088-9.

- Donaldson, Stephen E.; William A. Myers (1990). Rails through the orange groves, Volume II. Trans-Anglo Books, Glendale, CA. ISBN 0-87046-094-3.

- Duke, Donald (1995). Santa Fe: The railroad gateway to the American West, volume one. Golden West Books, San Marino, CA. ISBN 0-87095-110-6.

- Duke, Donald (1995). Santa Fe: The railroad gateway to the American West, volume Two. Golden West Books, San Marino, CA. ISBN 0-87095-110-6.

- Lewis, Oscar (1938). The Big Four. Alfred A Knopf, New York, NY.

- Hanft, Robert M. (1984). San Diego & Arizona: The impossible railway. Trans-Anglo Books, Glendale, CA. ISBN 0-87046-071-4.

- Harper's New Monthly Magazine, March 1855, Volume 10, Issue 58 complete text online

- Hill, Mary (1999). Gold: the California story. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21547-8.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for riches; gold fever and the making of California. Oakland, California, Berkeley and Los Angeles: Oakland Museum of California and University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21401-3.

- Moody, John (1919). The railroad builders: A chronicle of the welding of the states. Yale University Press, Haven, CT.

- Rawls, James J.; Walton Bean (2003). California: An interpretive history. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. ISBN 0-07-255255-7.

- Rawls, James J.; Orsi, Richard J., eds. (1999). A golden state: mining and economic development in Gold Rush California (California History Sesquicentennial Series, 2). Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21771-3.

- Robinson, W. W. (1948). Land in California. University of California Press, Los Angeles, CA.

- Thompson, Anthony W.; Robert J. Church; Bruce H. Jones (2000). Pacific Fruit Express. Signature Press, Wilton, CA. ISBN 1-930013-03-5.

- Wright, Ralph B. (1950). California's missions. Hubert A. and Martha H. Lowman, Arroyo Grande, CA.

- Yenne, Bill (1985). The history of the Southern Pacific. Brompton Books Corp., Greenwich, CT. ISBN 978-0-517-46084-9.

Further reading

- Cooper, Bruce C., ed. (2005). Riding the transcontinental rails: Overland travel on the Pacific Railroad 1865-1881. Polyglot Press, Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 1-4115-9993-4.

- Cooper, Bruce Clement (2010). The Classic Western American Railroad Routes. New York: Chartwell Books/Worth Press. ISBN 978-0-7858-2573-9.

- Deverell, William (1994). Railroad crossing: Californians and the railroad 1850–1910. University of California Press, Los Angeles, CA. ISBN 0-520-08214-1.

- Norris, Frank (1901). The Octopus: A Story of California. Doubleday. ISBN 0-14-018770-7.

- Thompson, Gregory Lee (1993). The passenger train in the Motor Age: California's rail and bus industries, 1910–1941. Ohio State University Press, Columbus, OH. ISBN 0-8142-0609-3.

External links

- California Rail Map

- The Impact of the Railroad: The Iron Horse and the Octopus

- Guide to Railroad History web links to primary and scholarly sources