Cameroon–Nigeria relations

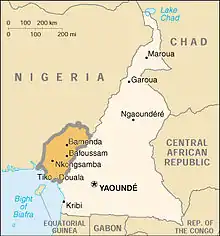

Relations between Cameroon and Nigeria were established in 1960, the same year that each country obtained its independence. Since then, their relationship has revolved in large part around their extensive shared border, as well as the legacy of colonial arrangements under which areas of Cameroon were administered as part of British Nigeria. The countries came close to war in the 1990s in the culmination of a long-running dispute over the sovereignty of the Bakassi peninsula. In the 21st century, however, a return to conviviality has been achieved, partly because the demarcation of their border has been formalised, and partly because the Boko Haram insurgency in the Lake Chad basin has necessitated increasingly close cooperation in regional security matters.

| |

Cameroon |

Nigeria |

|---|---|

1960s–1970s: Early diplomatic relations

In 1960, Cameroon and Nigeria acquired independence from France and Britain respectively, and they established bilateral relations in the same year.[1][2] On 6 February 1963, they signed an "Agreement of Friendship and Cooperation", a trade agreement, and a memorandum of understanding on the cross-border movement of persons and goods.[3] Once he had reconciled himself to Cameroon's loss of British Northern Cameroons to Nigeria , Ahmadou Ahidjo, the first president of the independent Republic of Cameroon, pledged in 1964 that, "We will see to it that our relations with Nigeria... should be at their best".[1]

Nigerian civil war

During the Nigerian civil war (1967–70), Ahidjo provided valuable support to Nigeria's federal military government, led by General Yakubu Gowon.[4][5] In November 1967, after initially declaring himself neutral in the conflict, Cameroon closed its border with Nigeria and banned shipments to Biafra of arms, medicines, foodstuffs, or other supplies. The Nigerian government was invited to use the Cameroonian village of Jabane as a base from which to monitor supplies entering its Calabar port.[6] Still more surprisingly, Ahidjo publicly lambasted the nations who supported the Biafran secessionists – a group which included not only African states like Gabon, Ivory Coast, and Tanzania, but also France, one of Cameroon's most important patrons.[6] Ahidjo was also appointed to the Organisation of African Unity mediation commission during the war, and after the war ended he mediated informally between Nigeria and the Francophone states which had recognised Biafran independence.[7]

This inaugurated "perhaps the finest hour" in 20th century Cameroon–Nigeria relations: during a state visit to Nigeria in September 1970, Ahidjo received Gowon's public praise for his support, and in 1972 the University of Lagos awarded him an honorary degree.[8] Further cooperation agreements followed: three in March 1972, including one on police cooperation, and an air services agreement in May 1978.[3]

Disputes in the border region

Background

On 11 February 1961, months after Nigerian independence, a plebiscite was held, under the supervision of the United Nations (UN), to establish the future of the areas along the Nigeria–Cameroon border which previously had been under British mandate. These two areas, Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons, belonged to German Cameroon until Germany's 1916 defeat in Cameroon during the First World War. Thereafter, they were assigned to British administration and governed as part of British Northern and Eastern Nigeria respectively, while the rest of Cameroon was assigned to French administration.[9] In the 1961 referendum, Southern Cameroons voted to reunify with Cameroon; while Northern Cameroons, which had deferred its decision at an earlier referendum in 1959, voted to reunify with Nigeria.[10] Ahidjo had campaigned for the total reunification of Cameroon, and he unsuccessfully protested the result of the northern vote at the International Court of Justice, alleging British and Nigerian interference, from "intimidation, open persecution and obstruction of all kinds, to shameless rigging".[11] The Cameroonian response to the referendum has been described variously as "strong official resentment"[12] or as "deep and long-lasting bitterness",[13] and Cameroon observed its anniversary for several years afterwards as an "official mourning day for the 'lost territories'".[12]

Anglophone Cameroon

The reunification of the former British Southern Cameroons with the rest of Cameroon has presented political problems for Cameroonian leaders, and these problems have occasionally become entangled with Cameroon–Nigeria relations. As Cameroonian politician A. S. Ngwana argued, articulating the so-called Anglophone problem, parts of Cameroon spent nearly fifty years – between 1916 and 1959 – under different colonial administrations, absorbing different cultures and modes of governance.[10] Moreover, during that same period, large numbers of eastern Nigerians, especially Igbo Nigerians, migrated to British Southern Cameroons.[14] Their central role in the regional economy provoked escalating xenophobia among Cameroonian residents, an "Igbo scare" which after the Second World War was harnessed to nationalist local politics.[15][16] After independence, from the mid-1960s, Ahidjo's regime took measures to dismantle efforts at Igbo self-organisation in the region, including banning ethnic associations like the powerful Igbo Union.[17] In the early 1970s, however, the Igbo increasingly joined the Nigerian Union in Cameroon, a legally recognised diaspora organisation that became an important pressure group for Nigerian interests in the country, as well as an important vehicle for their integration.[18]

Especially from the 1990s, the Cameroonian regime has worried that Nigerian residents are "natural allies" of emerging Anglophone secessionist movements among Cameroonians, notwithstanding the historical tensions between Cameroonians and Igbo.[19] The regime has been criticised for its "intimidating and extortionist" treatment of Nigerians in the south.[19][10] The tensions between the Cameroonian state and each respective group – the Nigerian migrants and the Cameroonian secessionists – were heightened by the conflict between Cameroon and Nigeria over the sovereignty of the border regions in which many of them resided.[20]

Bakassi border dispute

Although there is a long history of Cameroon–Nigeria boundary disputes, the most important has been the dispute over the sovereignty of the Bakassi peninsula, at the southernmost end of the Cameroon–Nigeria border.[20] The peninsula, located in the Gulf of Guinea between the Rio del Rey and Cross River State, was strategically important to both countries, both for its access to the port of Calabar – which housed the Eastern Command of the Nigerian Navy, as well as Nigeria's Export-Processing Zone – and for its oil resources.[21] Its population largely comprises fishermen of Nigerian citizenship.[22] In 1913, the so-called Ango-German Agreement, signed in London, had acknowledged that Bakassi belonged to the German protectorate of Cameroon. After the First World War, a Franco-British declaration in July 1919 placed it under the British Southern Cameroons, and it was therefore reunified with Cameroon after independence – an outcome which 59.5% of residents had supported in the 1961 referendum.[23]

In the period of warm bilateral relations following the Nigerian civil war, border talks under the Joint Nigeria–Cameroon Frontier Commission intensified, resulting in the signature of the 1975 Maroua Declaration, which delimited the maritime boundary between Cameroon and Nigeria and recognised Cameroonian sovereignty over Bakassi.[24] However, several weeks later, Gowon was deposed in a military coup d'état, and his successor, Murtala Muhammed, chastised Gowon for signing the agreement and refused to ratify it. Infuriated, Abidjo announced that Cameroon would not negotiate any further with Nigeria until Murtala had been replaced as head of state.[24] Over the next two decades, tensions escalated, bringing the countries to the "brink of war" in 1981 and inviting firefights on several occasions in the 1990s, after the Nigerian army had invaded Bakassi.[25]

International Court of Justice ruling

Abidjo's successor as president, Paul Biya, filed suit at the International Court of Justice on 29 March 1994.[26] Cameroon's claim to Bakassi was largely based on the Anglo-German agreement of 1913 and the 1975 Maroua Declaration. Nigeria, on the other hand, argued that the peninsula had been the territory of the chiefs of Old Calabar, who had transferred their title to Nigeria upon its independence. As support for this argument it pointed to the Nigerian collection of taxes in the region, the widespread use of Nigerian passports by its residents, and other signs that the Nigerian state had been intimately involved in the governance of the peninsula.[27] On 10 October 2002, after more than eight years of hearings and deliberations, the court ruled in favour of Cameroon, instructing Nigeria to withdraw immediately from the region.[28]

Although Nigeria initially protested the decision, and although it caused significant unrest in Bakassi, Olusegun Obasanjo's regime largely cooperated with the ruling.[28] In June 2006, at the Greentree estate in Long Island, New York, the countries signed the Greentree Agreement, which required Nigeria to withdraw its troops from Bakassi by 4 August 2008, and also required Cameroon to protect the rights of the Nigerian citizens who lived in Bakassi.[29] The transfer of the territory to Cameroon proceeded peacefully under the agreement.[30] The Cameroonian government now presents the dispute as a "misunderstanding", and its resolution as "a model of peaceful conflict resolution in Africa."[31]

Cameroon–Nigeria Mixed Commission

At the request of Biya and Obasanjo, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan established the Cameroon–Nigeria Mixed Commission to negotiate a smooth implementation of the International Court of Justice's 2002 ruling. The commission's responsibilities included demarcating the entirety of the Cameroon–Nigeria border, facilitating cross-border cooperation and troop withdrawals from Bakassi, and protecting the rights of locals.[30] The commission was chaired by Mohamed Ibn Chambas and had met 38 times by 2015.[31] As of July 2019, 2,001 kilometres of boundary (out of an estimated 2,100 kilometres) had been surveyed and agreed to by both countries, including the border at Bakassi.[30] In May 2007 in Abuja, the commission finalised the maritime boundary, but in 2015, the Cameroonian government reported that "a few tens of kilometres remain[ed] a stumbling block" in finalising the land boundary.[31]

2010s–present: Cooperation against Boko Haram

Over the past decade, Cameroon and Nigeria have undertaken bilateral and multilateral cooperation in the fight against terrorist group Boko Haram. In Boko Haram's early years, Biya took the view that it was "a domestic Nigerian issue".[32] After 2010, however, the insurgency spilled over from Nigeria into the Lake Chad basin, including the underdeveloped Far North of Cameroon, which has served as a recruitment ground for Boko Haram, as well as a refuge from Nigerian security services.[33][32] There were several Boko Haram kidnappings in Cameroon, including of foreign nationals and of the wife of Cameroon's deputy prime minister.[34] The exodus of refugees from Nigeria became a humanitarian and security risk,[35] and, as attacks inside Cameroon escalated, Cameroonians were also displaced – 170,000 by 2017.[36] Cross-border livestock theft has also increased: the World Bank estimates that, between 2013 and 2018, Boko Haram stole from Cameroonians at least 17,000 heads of cattle (worth around US$6 million) for sale in Nigeria.[37]

Despite Nigeria's occasional complaints that Cameroon was not taking sufficient action against Boko Haram,[38] since mid-2014 Cameroon adopted a much more active stance, deploying its first contingent of troops to the Nigerian border in May of that year.[39] There remain concerns that Nigeria and Cameroon continue to engage in a spirit of "mutual suspicion", undermining communication between them.[40] Nonetheless, security cooperation appears to have improved relations between the two countries and their heads of state,[36] including through a series of regular bilateral meetings from around 2012.[41] Perhaps evincing these closer ties, at a bilateral meeting in 2021, the Cameroonian Minister for Territorial Administration, Atanga Nji Paul, reassured Nigeria of Biya's "determination never to allow his territory to be used as training grounds for terrorists against a friendly and brotherly country like Nigeria".[42]

Trans-Border Security Committee

On 28 February 2012 in Abuja, Nigeria and Cameroon signed an agreement to establish the Cameroon–Nigeria Trans-Border Security Committee, intended to deepen cooperation on border security and on issues relating to terrorism, weapons smuggling, and illegal migration.[43] It meets twice a year, with the countries taking turns to host. The first session was held on 6–8 November 2013 in Yaoundé,[31] and the eighth session on 24–26 August 2021 in Abuja.[42]

Multi-National Joint Task Force

In 2014, Cameroon joined the Multi-National Joint Task Force, established by Nigeria and comprising the Lake Chad countries (and Benin). This followed a Lake Chad Basin Commission summit held in Paris in May 2014, at the invitation of French President Francois Hollande, at which Biya announced the states' intention to "declare war" ("declarer la guerre") against Boko Haram.[36] The task force seeks to enhance regional counter-terrorism cooperation, particularly in the fight against Boko Haram, and including by coordinating patrols, coordinating border surveillance, and pooling intelligence.[44]

Contemporary diplomatic and economic relations

As of 2015, Cameroon maintained a consulate general in Lagos and a consulate in Calabar; while Nigeria had consulate generals in Douala and Buea, and planned to open another in Garoua.[31] According to the Cameroonian government, nearly four million Nigerians live in Cameroon.[31] Both countries are members of the Lake Chad Basin Commission and the African Union.

The initial bilateral trade agreement of 1963 was revised in January 1982 and April 2014,[3] and Nigeria is a major source of imports to Cameroon.[31] Although the volume of trade is difficult to estimate because much of it is informal, in 2013 the World Bank estimated that Cameroon exported US$64 million annually to Nigeria (primarily paddy rice, other agricultural products, and soap), while Nigeria exported about $176 million to Cameroon (primarily cosmetics, plastics, footwear, and other general merchandise).[45] A large share of Cameroonian fish production was also exported to Nigeria. However, the Boko Haram insurgency in the north of both countries has disrupted many of the traditional trade routes, reducing trade between them.[45]

Notes

- Amin 2020, p. 5.

- Shulika 2021, p. 103.

- Shulika 2021, p. 104.

- Kofele-Kale 1981, p. 214-5.

- Konings 2005, p. 286.

- Amin 2020, p. 6.

- Kofele-Kale 1981, p. 214.

- Amin 2020, p. 7-8.

- Shulika 2021, p. 101.

- Okoi 2016, p. 51.

- Amin 2020, p. 4-5.

- Kofele-Kale 1981, p. 198.

- Konings 2005, p. 290.

- Konings 2005, p. 279.

- Konings 2005, p. 280.

- Amaazee 1990.

- Amin 2020, pp. 5–6.

- Konings 2005, pp. 287–8.

- Konings 2005, pp. 288, 291.

- Konings 2005, p. 289.

- Okoi 2016, pp. 42, 50, 55.

- Konings 2005, pp. 289, 291.

- Amin 2020, pp. 7–8.

- Konings 2005, p. 291.

- Cornwell 2006, pp. 51–3.

- Amin 2020, p. 12.

- Konings 2005, pp. 289–90.

- Cornwell 2006, p. 54.

- Amin 2020, p. 14.

- United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel 2019.

- Presidency of the Republic of Cameroon 2015.

- Amin 2020, p. 15.

- Akinlabi 2021, pp. 104, 108.

- Amin 2020, p. 16.

- Akinlabi 2021, p. 104.

- Amin 2020, p. 17.

- Walkenhorst 2021, p. 306.

- Akinlabi 2021, p. 108.

- Kindzeka 2014.

- Akinlabi 2021, p. 108-9.

- Akinlabi 2021, p. 100.

- Bainkong 2021.

- Akinlabi 2021, p. 107.

- Akinlabi 2021, p. 106.

- Walkenhorst 2021, p. 301-2.

Bibliography

- Akinlabi, Akinkunmi Afeez (2021). "Impact of Boko Haram on Nigeria–Cameroon Relations, 2011–2015". African Journal of Terrorism and Insurgency Research. 2 (2): 99–112. doi:10.31920/2732-5008/2021/v2n2a4 (inactive 1 August 2023). hdl:10520/ejc-aa_ajtir_v2_n2_a4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Amaazee, Victor Bong (1990). "The 'Igbo Scare' in the British Cameroons, c. 1945-61". The Journal of African History. 31 (2): 281–293. doi:10.1017/S0021853700025044. JSTOR 182769.

- Amin, Julius A. (2020). "Cameroon's relations toward Nigeria: a foreign policy of pragmatism". Journal of Modern African Studies. 58 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0022278X19000545. S2CID 214047726.

- Ani, Kelechi Johnmary; Kinge, Gabriel Tiobo Wose; Ojakorotu, Victor (2018). "Nigeria-Cameroon Relations: Focus On Economic History and Border Diplomacy". Journal of African Foreign Affairs. 5 (2): 147–166. doi:10.31920/2056-5658/2018/v5n2a8. ISSN 2056-564X. JSTOR 26664067. S2CID 158283743.

- Bainkong, Godlove (2021-08-27). "Cameroon, Nigeria Trans-Border Security - New Ways of Collaboration Mapped Out". Cameroon Tribune.

- Cornwell, Richard (2006). "Nigeria and Cameroon: Diplomacy in the Delta". African Security Review. 15 (4): 48–55. doi:10.1080/10246029.2006.9627621. S2CID 144062623.

- Kindzeka, Moki Edwin (2014-05-26). "Cameroon, Chad Deploy Troops to Fight Boko Haram". ReliefWeb.

- Kofele-Kale, Ndiva (1981). "Cameroon and Its Foreign Relations". African Affairs. 80 (319): 196–217. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097305. JSTOR 721321.

- Konings, Piet (2005). "The Anglophone Cameroon-Nigeria Boundary: Opportunities and Conflicts". African Affairs. 104 (415): 275–301. doi:10.1093/afraf/adi004. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 3518445.

- Lukong, V. (2011). The Cameroon-Nigeria Border Dispute. Management and Resolution, 1981-2011: Management and Resolution, 1981-2011. Cameroon: Langaa Research and Publishing Common Initiative Group. ISBN 978-9956-726-24-0.

- Nwokolo, Ndubuisi N. (2020). "Peace-building or structural violence? Deconstructing the aftermath of Nigeria/Cameroon boundary demarcation". African Security Review. 29 (1): 41–57. doi:10.1080/10246029.2020.1734644. S2CID 219083550.

- Okoi, Obasesam (2016). "Why Nations Fight: The Causes of the Nigeria–Cameroon Bakassi Peninsula Conflict". African Security. 9 (1): 42–65. doi:10.1080/19392206.2016.1132904. ISSN 1939-2206. JSTOR 48598917. S2CID 147365941.

- Presidency of the Republic of Cameroon (2015). Nigeria: Our Neighbour, Our Partner (PDF) (Report).

- Shulika, Lukong Stella (2021). "Nigeria-Cameroon Relations: An Appraisal". In Tella, Oluwaseun (ed.). Springer International. Cham: Springer. pp. 101–112. ISBN 978-3-030-73374-2.

- United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (2019-07-09). "A Success in the Resolution of Boundary Dispute". The Cameroon–Nigeria Mixed Commission.

- Walkenhorst, Peter (2021). Technical Paper 7: Trade Patterns and Trade Networks in the Lake Chad Region (Report). Washington, D. C.: World Bank.