Cândido Rondon

Marshal Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon (5 May 1865 – 19 January 1958) was a Brazilian military officer most famous for his telegraph commission and exploration of Mato Grosso and the Western Amazon Basin, as well as his lifelong support for indigenous Brazilians. He was the first director of Brazil's Indian Protection Service or SPI (later FUNAI) and supported the creation of the Xingu National Park. The Brazilian state of Rondônia is named after him, and he has even been called "the Gandhi of Brazil."[1]

Cândido Rondon | |

|---|---|

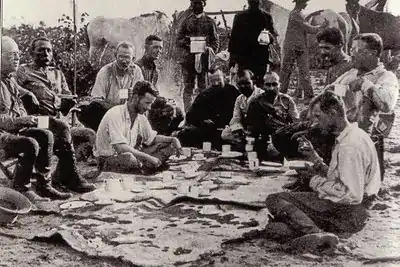

Rondon in 1910 | |

| Birth name | Cândido Mariano da Silva |

| Nickname(s) | Marshal Rondon |

| Born | 5 May 1865 Santo Antônio do Leverger, Mato Grosso, Empire of Brazil |

| Died | 19 January 1958 (aged 92) Rio de Janeiro, Federal District, Brazil |

| Buried | São João Batista Cemetery, Rio de Janeiro |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1881–1955 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Military Corps of Engineers Strategic Telegraph Lines Commission Indian Protection Service |

| Battles/wars | Proclamation of the Republic Revolta da Armada Revolution of 1930 |

| Awards | Combat Cross David Livingstone Centenary Medal Explorers Club Medal Order of Columbus |

| Spouse(s) |

Francisca "Chiquinha" Xavier

(m. 1896) |

| Other work | Writer; engineer |

| Signature | |

Biography

Early life

Cândido Mariano da Silva was born on 5 May 1865 in Mimoso, a small village in the state of Mato Grosso. His father, Cândido Mariano da Silva Sr., was of Portuguese, Spanish, and Guaná (an indigenous group) ancestry, and died of smallpox in 1864, prior to Rondon's birth. His mother, Claudina Freitas Evangelista, was descended from the Terena and Bororo indigenous peoples.[2] She died two years after giving birth to Rondon.[3] He was raised by his grandparents until their death, and then by his uncle, Manuel Rodrigues da Silva Rondon, from whom he took the name Rondon.[4]

After finishing high school at the age of 16, he taught elementary school for two years, and then joined the Brazilian army. He enrolled in the 3rd Regiment of Horse Artillery in 1881. Among other studies, he studied Mathematics and Physical and Natural Sciences at the Superior School of War. On joining the military, he entered officer's school and graduated in 1888 as a second lieutenant. He was also involved with the Republican coup that overthrew Pedro II, the last Emperor of Brazil.

As an army engineer

The republican government was worried about the western region of Brazil, very isolated from the great centers and border regions. In 1890, he was commissioned as an army engineer with the Telegraphic commission, and helped build the first telegraph line across the state of Mato Grosso. This telegraph line was finally finished in 1895, and afterwards, Rondon started construction on a road that led from Rio de Janeiro (then the capital of the republic) to Cuiabá, the capital of Mato Grosso. Until this roadway was complete, the only way between these two cities was by river transport. Also during this time, he married his wife, Francisca (Chiquinha) Xavier. Together, they had 7 children. From 1900 to 1906, Rondon was in charge of laying telegraph lines from Brazil to Bolivia and Peru. During this time he opened up new territory, and was in contact with the warlike Bororo of western Brazil. He was so successful in pacifying the Bororo, that he completed the telegraph line with their help. Throughout his life, Rondon laid over 4,000 miles of telegraph line through the jungles of Brazil.

Marshall Rondon was honored with the title "Patron of the Communications Corps of the Brazilian Army", by Decree No. 51,960, of 26 April 1963.

Later life

After the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition of 1914, Rondon worked until 1919 mapping the state of Mato Grosso. During this time he discovered some more rivers, and made contact with several indigenous tribes. In 1919, he became chief of the Brazilian Corps of Engineers, and the head of the Telegraphic Commission.

In 1924 and 1925, he led army forces against a rebellion in the state of São Paulo. From 1927 to 1930, Rondon was put in charge of surveying all of the borders between Brazil and its neighbors. In 1930, he was interrupted by the Revolution of 1930, and he resigned from his position as head of SPI. During 1934–1938, he was in charge of a Diplomatic Mission, to mediate a dispute between Colombia and Peru over the town of Leticia. In 1939, he resumed his directorship of SPI, and expanded the service to new territories of Brazil. In the 1950s he supported the Villas Boas brothers' campaign, which faced strong opposition from the government and the ranchers of Mato Grosso and led to the establishment of the first Brazilian National Park for indigenous people along the Xingu River in 1961.[5]

On 5 May 1955, the date of his 90th birthday, he was awarded the title of Marshal of the Brazilian Army, granted by the National Congress. In 1957, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the Explorers Club of New York. And decades earlier, Albert Einstein had recommended Rondon to the Nobel committee.[1] He died in 1958 in Rio de Janeiro at the age of 92.

Telegraph Commission

Cândido Rondon headed up a large-scale military operation to expand telegraph lines into the Brazilian Amazon, this group has also been called “The Rondon Commission.”[6] Rondon was, by this time, a devout follower of positivist beliefs and he believed his purpose was to unite all peoples of Brazil through his work in the commission. He had an unrelenting belief that progress should be made as quickly as possible and that indigenous peoples needed to be incorporated into society as quickly as possible to achieve this.[6] Rondon showed concern as to how these indigenous groups were incorporated into modern society and he made it his mission to “guide” them to a more “civilized” life in what he viewed as a peaceful manner.[6]

However, some critics believe that Rondon's concern about indigenous groups and unification was fraudulent.[7] These critics posit that this mission was mainly a military operation with a state focus on seizing and defining borders for defense purposes along with creating new opportunities for colonization and economic expansion.[7] They believe this undermines the view that Rondon was a hero of unification and pacification towards previously uncontacted or independent indigenous tribes.[7]

The Rondon Commission was successful in its goal to open up the Amazon to economic development. Many new settlements appeared along the telegraph lines. New settlers desired a piece of this land for farming and ranching, but one side effect was the displacement of indigenous tribes like the Bororo.[7]

Explorations

As a result of Rondon's competence in constructing telegraph lines, he was put in charge of extending the telegraph line from Mato Grosso to the Amazon. In the course of constructing the line, he charted the Juruena River (an important tributary of the Tapajós River in northern Mato Grosso) and, in addition, he made peaceful contact with the Nambikwara tribe, which had until then killed all Westerners they had come in contact with.[8] He also (in 1911) visited the ruins of the eighteenth century Real Forte Príncipe da Beira, the greatest historical relic of Rondônia, which had been abandoned in 1889, and was promoted as major of the Corps of Military Engineers, responsible for building the Cuiabá telegraph line to Santo Antonio do Madeira, the first to reach the Amazon region, which was called the "Rondon Commission". His works developed from 1907 to 1915. At the same time, the Madeira-Mamoré Railroad was being built, which together with the Rondon telegraphic exploration and integration helped to occupy the region of the present state of Rondônia.

In May 1909, Rondon went on his longest expedition. He set out from the settlement of Tapirapuã in northern Mato Grosso heading northwest to meet up with the Madeira River, which is a major tributary of the Amazon River. By August, the party had eaten all of its supplies, and had to subsist on what they could hunt and gather from the forest. By the time they reached the Ji-Paraná River, they had no supplies. During their expedition they discovered a large river between the Juruena, and Ji-Paraná River, which Rondon named the River of Doubt. To reach the Madeira, they built canoes, and reached the Madeira on Christmas Day, 1909.

When Rondon reached Rio de Janeiro, he was hailed as a hero, because it was believed that he and the expedition had died in the jungle. After the expedition, he became the first director of the Brazilian Government's Indian Protection Agency, or the SPI.

In September 1913, Rondon was struck by a poisoned arrow from the Nambikwara Indians. In 1914, with the Rondon Commission, he built 372 km of lines and five more telegraph stations: Pimenta Bueno, President Hermes, Presidente Pena (later Vila de Rondônia and present Ji-Paraná), Jaru and Ariquemes, in the area of the present state of Rondônia. On January 1, 1915, he completed his mission with the inauguration of the telegraph station in Santo Antônio do Madeira.

The 52nd meridian west is also a geographical reference for the history of communications in Brazil. Rondon was the second human being to receive in his honor a meridian in his name. He fulfilled missions by opening roads, clearing lands, launching telegraph lines, mapping the land, and establishing cordial relations with the Indians. He maintained contact with several indigenous peoples.

Expedition with Roosevelt

In January 1914, Rondon left with Theodore Roosevelt on the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition, whose aims were to explore the River of Doubt. The expedition left the Tapiripuã, and reached the River of Doubt on 27 February 1914. They did not reach the mouth of the river until late April, after the expedition had suffered greatly. During the expedition, the river was renamed the Rio Roosevelt.

The Adventure down the River of Doubt was the most difficult of Roosevelt's life. All the men except Rondon suffered from ailments and constant maladies.

Positivism/Comtism

From 1898 onward Rondon was an orthodox member of the Igreja Positivista do Brasil (Positivist Church of Brazil), which is a Religion of Humanity based on the thought of Auguste Comte. The creed he embraced from it emphasized naturalism, science, and altruism rather than any supernatural forces.[9]

Positivism follows the goal of preventing social unrest by convincing the lower classes to accept the domination of the upper classes in exchange for things such as material benefits, guidance, and general improvement.[10] Comte postulated that there are three stages of social evolution that humankind passes through, and placed special emphasis on scientific thought, industrialization, modernization, and general reform. These characteristics in particular helped it spread to Brazil following the Paraguayan War (1865–1870), when many Brazilians questioned the foundations of their society.[10]

Rondon first encountered positivism in 1885 as a student at the Military Academy in Rio de Janeiro, where it was taught as a form of spreading republicanism. He converted and became part of a growing group of Positivist officers and cadets at the academy. Although Brazilian enthusiasm for positivism was already on the decline by 1891, Rondon became a passionate lifelong member of the Orthodox Positivist Church, believing that Brazil, and the world with it, would eventually accept positivism because it was so rational.[11]

Positivism ultimately shaped Rondon's outlook on life, his ideas about interracial relations, and his plans for national development. He once told his men that he wanted to create a “political utopia,” and believed that his telegraph line aided in the evolution of humanity due to the large number of tribes he came in first contact with during the project. Unfortunately, Rondon's positivism ultimately led to fights with officials in the more powerful Catholic Church, limiting the influence and impact of his work in the long term.[11]

The Indian Protection Service (SPI)

Rondon was invited to be the founding leader of the Serviço de Proteção ao Índio (SPI), the Indian Protection Service, by the Brazilian Minister of Agriculture Rodolfo Miranda in 1910. On accepting the position, Rondon explained to Miranda the importance of Positivism in his policies with the organization.[6] He believed that, rather than allow Christian missionaries to forcibly assimilate the indigenous peoples, the best method would be to gradually and nonviolently lead them by example into the more civilized world. Rondon and other Positivists argued for the protection of indigenous peoples and the defense of their lands, saying that rather than being racially inferior, they were simply at an earlier stage of Positivist evolution.[6]

Rondon led the organization until the Brazilian Revolution of 1930, leaving many of his initial plans to be only in theory. The goal of SPI was to protect the well-being of natives, and Rondon created its motto: “die if need be, never kill.” Reports published as late as 1960 declared that the SPI had “entirely reached its objectives without betraying” this slogan, even claiming that despite “dozens” of SPI team members being murdered by poisoned arrows, they did not kill a single indigenous person.[12] Instead, they supposedly operated using pacification techniques that Rondon developed while the head of the Mato Grosso-Amazon Strategic Communications and Telegraph Commission, utilizing a “flirting” technique to allow native tribes to choose to engage with them before officially taking over.[13]

However, beginning shortly before Rondon's death in 1958, severe corruption and abuses of indigenous peoples were revealed to have been committed by those working with SPI. The organization was disbanded in disgrace in 1967, and a similar organization, Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI), replaced it later that year.[14]

Homages

Marshal Cândido Rondon is considered one of the foremost Brazilian heroes and patriots and has thus been honoured by the population and government in many ways. He is the "Father of Brazilian Telecommunications" and 5 May is the National Day of Telecommunications, established in his honour. Had the glory of having his name written in letters of gold in massive Book of the Geographical Society of New York.

- State of Rondônia

- Fundação Cândido Rondon

- Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul

- Municipality of Rondon, Pará

- Municipality of Marechal Cândido Rondon, Paraná

- Municipality of Marechal Rondon, Mato Grosso

- Municipality of Rondonópolis, Mato Grosso

The state of Rondônia

The state of Rondônia - Faculdade Marechal Rondon, São Manuel, São Paulo

- Faculdades Integradas Cândido Rondon , Cuiabá, Mato Grosso.

- Project Rondon

- Museu Rondon, Federal University of Mato Grosso

- Marechal Rondon Library, Museu do Índio, Fundação Nacional do Índio, Botafogo, Rio de Janeiro

- Bosque Municipal Marechal Rondon, Londrina, Paraná

- Marechal Rondon International Airport, Cuiabá/Várzea Grande, Mato Grosso

- Marechal Rondon Highway, State of São Paulo

- Rondon's marmoset (Mico rondoni), a small monkey.

- Rondon's tuco-tuco (Ctenomys rondoni), a rodent.

- Rondon's gymnophthalmid (Rondonops), a lizard genera.[15]

In addition, thousands of streets, schools and other urban features and organizations have received Rondon's name.

Notes and references

- Slade, Rachel. "A Biography Sheds Light on an Unknown Brazilian Hero". nytimes.com. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- Thomé, Nilson; Thomé Pollyana. Cyriacolândia - território da família Rondon no Pantanal. Campo Grande: Edição do Autor, 2015, p. 13s

- Lucien Bodard, Green Hell (New York, 1971) p. 10

- Donald F. O'Reilly, "Rondon: Biography of a Brazilian Republican Army Commander," New York University, 1969

- From the first expedition to the creation of the Park, pib.socioambiental.org

- Diacon, Todd A. (2004). Stringing together a nation : Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon and the construction of a modern Brazil, 1906–1930. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822332107. OCLC 52429358.

- Langfur, Hal (1999). "Myths of Pacification: Brazilian Frontier Settlement and the Subjugation of the Bororo Indians". Journal of Social History. 32 (4): 879–905. doi:10.1353/jsh/32.4.879. ISSN 0022-4529. JSTOR 3789895.

- Baker, Daniel ed. Explorers and Discoverers of the World. Detroit: Gale Research, 1993 Pg 483

- Stringing Together a Nation: Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon and the ... By Todd A. Diacon: pgs 83–84

- Diacon, Todd A. (2004). Stringing Together a Nation : Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon and the Construction of a Modern Brazil, 1906–1930. Duke University Press Books. pp. 80–82. OCLC 743402628.

- Diacon, Todd A. (2004). Stringing Together a Nation : Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon and the Construction of a Modern Brazil, 1906–1930. Duke University Press Books. p. 85. OCLC 743402628.

- Ribeiro, Darcy (1960). "The Social Integrations of Indigenous Populations in Brazil". International Labour Review: 320–327.

- Ribeiro, Darcy (1960). "The Social Integrations of Indigenous Populations in Brazil". International Labour Review: 328.

- "What Future for the Amerindians of South America? Minority Rights Group Report 15" (PDF). Minority Rights Group. pp. 20-23.

- Colli GR, Hoogmoed MS, Cannatella DC, Cassimiro J, Gomes JO, Ghellere JM, Nunes PMS, Pellegrino KCM, Salerno P, De Souza SM, and Rodrigues MT. 2015. Description and phylogenetic relationships of a new genus and two new species of lizards from Brazilian Amazonia, with nomenclatural comments on the taxonomy of Gymnophthalmidae (Reptilia: Squamata). Zootaxa 4000:401-427.

Bibliography

- (in French) Michel Braudeau, « Le télégraphe positiviste de Cândido Rondon », in Le rêve amazonien, éditions Gallimard, 2004 (ISBN 2-07-077049-4).

See also

External links

- Candido Rondon: A friend of the Indians Archived 13 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine is a good site to learn more about Rondon's involvement with Funai.

- Candido Rondon: Explorer, Geographer, Peacemaker: 1865–1958 has a timeline and good information about Rondon's life and work.

- Works by Cândido Rondon at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)