Casa do Sítio da Ressaca

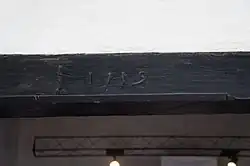

The Casa do Sítio da Ressaca is a Bandeirista-style building,[1] a remnant of the Brazilian colonial period, located in the Jabaquara district of the city of São Paulo. Located on the old road to Santo Amaro. The house was built in 1719, as attested by inscriptions found on the main door and tiles. Some of its roof tiles are original and bear inscriptions from the 18th century, such as the date of manufacture and the name of the potter. The doors and jambs, in canela-preta, are also original.[2]

| Casa do Sítio da Ressaca | |

|---|---|

Façade of the Casa Sítio da Ressaca | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Bandeirista |

| Location | São Paulo, Brazil |

| Coordinates | 29°39′03″N 46°38′42″W |

| Completed | 1719 |

| Awards and prizes | Listed property by CONDEPHAAT (1972) |

The name of the ranch is likely due to the Ressaca stream, also called Fagundes and Ressaca, that bathed its surroundings. Built with rammed earth, the house adopts an asymmetric plan, not very common in the Bandeirista residences. It has windows and doors with side lintels, while the roof is pitched in two parts.

Overview

The house was used until 1969 when it was expropriated for the construction of the São Paulo subway. Preserved by the Council for the Defense of Historical, Archaeological, Artistic and Tourist Heritage (CONDEPHAAT), the Casa Sítio da Ressaca[3] was restored in 1978 under the commitment of the Municipal Urbanization Company (EMURB) and was re-inaugurated in 1979. In 1986, it suffered a small fire causing the house to undergo restoration again in 1987, 1988, 1990, and 2002.[4]

Also in 2002, the Casa do Sítio da Ressaca was occupied by the Acervo da Memória e do Viver Afro-Brasileiro.[5] It currently contains exhibitions and activities focused on Afro-Brazilian memory, and since 1990, it is part of the Jabaquara Cultural Center, hosting events, exhibitions, and also the Paulo Duarte Municipal Library.[6]

The current address of Casa Sítio da Ressaca is Rua Nadra Raffoul Mokodsi, 3, Jabaquara, São Paulo.[7]

History

Sergeant Major Lopes de Medeiros was the first owner of Sítio da Ressaca, at the time called Sítio Piranga. The farm was sold to Captain Manual de Avilla, and in 1700 was re-sold to Captain Agostinho de Macedo. The site's headquarters, the house still in the region and preserved, was likely built in 1719, as suggested by the number "1719" engraved on the main door. The house's roof tiles also show the year they were manufactured (1713, 1714, and 1716). There are records that Maria Vasconcellos, granddaughter of the Governor of the Captaincy of São Vicente, Captain-Mor Antônio Aguiar Barriga, had a house built in that region, but there is no indication that this would be the same house that remains to this day in Jabaquara.[8]

The name "Ressaca" appears for the first time in 1780, registered by Teresa Paula de Jesus Fernandes, owner of the property, who asked for the measurement and demarcation of Sítio da Ressaca, which would reach the lands of Father Domingos Gomes de Albernáz. For the measurement to be made, Teresa Paula de Jesus Fernandes gathered old titles, in which it was stated that Sergeant Major Lopes de Medeiros was the original owner of the sítio da Ressaca, before 1700. Teresa Paula de Jesus Fernandes donated part of the land to the manumissioned Francisco Raposo, sold another part to Padre Félix José de Oliveira, and another to Beata Úrsula.[8]

In 1827, Sítio da Ressaca belonged to Padre Vicente Pires da Motta, who sold it that year to Jorge Heath. The ranch was re-sold to Guilherme Hopkins and later to Henrique Henriqueson. In 1853, the house was purchased by Francisco Antônio Mariano. His widow, Dona Justina Mariano Peruche, sold the farm to one of her sons, Felício Antônio Mariano Fagundes, who united the Ressaca Farm, the Simão Farm, and the Olho D'água Farm under the same name, "Ressaca". From 1860 to 1900, the farm belonged to Felício A. Mariano Fagundes, and with his death, his heirs divided the property. The part containing the house was sold in 1908 to Antonio Cantarella, responsible for the urbanization of the Jabaquara neighborhood, and was a family farm until 1969. On this occasion, there was a new division of the area, with one part being allotted and transformed into what is today the Jardim Metropolitano. Another part was expropriated by the São Paulo subway, to build a maneuvering patio.[8]

After the subdivision, the local landscape was disfigured[8] and the house was expropriated in 1978 along with a 1-hectare plot of land around it. After the fire in 1986, the house underwent another restoration and ended up being listed by IPHAN. After this, it became part of the Jabaquara Cultural Center and, since 1990, it has housed the Afro-Brazilian Memory and Living Collection, gathering objects related to the presence of black people in São Paulo.[9]

Heritage site

Houses such as the headquarters of Sítio da Ressaca only had their historical and artistic value recognized in the 20th century, from work undertaken by figures such as Mário de Andrade and Luis Saia. Mário de Andrade, a modernist poet, was also the director of the São Paulo office of the Institute for National Historic and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). Mário's work in the agency was between 1937, the year IPHAN was founded, and 1939. During this period, the director established the line of work of the São Paulo office, privileging the conservation of buildings from before the imperial period, which was in line with the modernist ideals of Mário de Andrade - to build the national memory from the colonial vestiges. He surveyed documents reconstituting the Sítio da Ressaca for IPHAN to recognize its historical value.[8]

Mário de Andrade's assistant, Luis Saia, took over the direction of the São Paulo IPHAN from 1939 until 1975 and became an emblematic figure of the body.[10] Faced with the advances of the subway in the Jabaquara region, Luis Saia filed a lawsuit with the Council for the Defense of Historical, Archaeological, Artistic and Tourist Heritage (CONDEPHAAT) to have the Sítio da Ressaca headquarters properly listed and, consequently, protected from expropriation and construction in the region. The listing was decreed in 1972, based on the historical value of the property. However, Casa Sítio da Ressaca was in a state of abandonment. Saia recommended that the property and the area around it "criminally deformed by furnishing greed" be restored.[11]

However, nowadays, the Casa do Sítio da Ressaca has exhibits and activities focused on the memory of the Afro-Brazilian presence in the region, as well as traditions and manifestations of popular culture. From 1991 to 2002, it housed the Afro-Brazilian Memory and Living Collection.[6]

Restoration

Between 1978 and 1979, the Casa Sítio da Ressaca was restored, following the guidelines of the Cura/Jabaquara Project. The project, managed by the Municipal Urbanization Company (EMURB), was responsible for the reformulation of Jabaquara before the construction of the first subway line (North-South), today known as the Blue Line. Cura/Jabaquara foresaw the rescue of the house and the surrounding area through the following procedures:[8]

- Expropriation of the lots where the house was located, as well as the neighboring lots;

- Restoration of the house;

- Remodeling of its surroundings utilizing the expropriation of the neighboring lots and the implantation of a square;

- Installation of an annex, where the Jabaquara Cultural Center is located;

- Establishment of occupation guidelines for the surroundings of the headquarters, to preserve the views of the house.[8]

Architect Gustavo Neves da Rocha Filho was hired to design the building for the Jabaquara Cultural Center. The landscape designer Rosa Grena Kliass designed the square. Architect Antônio Luiz Dias de Andrade coordinated the restoration of the Sítio da Ressaca headquarters. Archeologist Marlene Suano was responsible for the archeological research on the house, and engineer Péricles Brasiliense Fusco was the structural consultant. The restoration was undertaken by the company PEC - Planejamento, Engenharia e Construção Ltda. and the works were supervised by EMURB architects with the Department of Historical Heritage (DPH).[8]

The house was expropriated in 1978 along with a 1-hectare piece of land around it, and the restoration, which in its beginning already showed the unfavorable situation in which the house found itself, was completed about a year after the beginning of the works. Not only the restoration of the building but also the revitalization of Sítio da Ressaca was accomplished, since it was decided to rebuild a hill located on an elevation on the land around the house, making use of a piece of land left over from the subdivision of Sítio da Ressaca, to improve the support of the walls. The site was practically redone in an attempt to recompose the original relief of the farm. In 1986, the building suffered a fire, which earned it further restoration work and the IPHAN (National Institute for the Artistic and Historic Heritage) declared it a National Heritage Site. After that, it became part of the Jabaquara Cultural Center and, since 1990, it has housed the Afro-Brazilian Memory and Living Collection, gathering objects referring to the presence of black people in São Paulo.[12]

Archaeological study

The archaeological research, carried out between 1978 and 1979, led by Marlene Suano, covered strategic points in the house, opening cuts of up to 80 cm in the floor that would serve as guides in the search for architectural evidence that could bring more information about the daily life of those who lived there. The objects ranged from metallic buttons, river shells, coins, glass bottle caps, white crockery, to other fragments such as bones, iron, pieces of charcoal, and charred sticks. In addition, holes were also found in the dirt floor that would correspond to the use of stakes that were probably used as support for hammocks and household utensils. Because of these observations, sections of this environment were purposely left uncovered so that a piece of the rammed earth foundation of an old wall that existed at the site can be seen.[13]

Bandeirista architecture

Rural constructions from São Paulo's colonial period, such as the Casa Sítio da Ressaca, are classified as Bandeirista architecture. The term is used to define the main buildings of farms and ranches, built between the 17th and 18th centuries.[14]

The Casa Sítio da Ressaca, as well as the other Bandeirista houses, was built with the rammed earth technique, of Arab origin, in which forms and pestles are used to compact a thick mass of clay, gravel and other various materials. The benefit of this technique is that, if well employed, it guarantees greater sustainability in construction.[14] Such technique was very present in São Paulo's constructions between the 16th century and the first half of the 19th century, characterizing the São Paulo architecture of that time, being the reflection of a cultural persistence resulting, above all, from the isolation caused by the difficulty of crossing the Serra do Mar.[15]

The walls of the Casa Sítio da Ressaca were built with the use of wooden forms, in the shape of large boxes, called "taipas". The clay mass is inserted into the boxes and compressed with the use of pestles. The "taipa" is then placed next to the first mass so that the procedure is repeated, and thus, horizontally, the mass is placed. Once the first layer is finished, the new layers begin, until the walls are properly erected. The internal walls are originally made of wattle and daub.[16]

The main house of Sítio da Ressaca has few rooms, only six, including the porch. The roof is of the gable type, which was common among some buildings of the period. The doors and windows are made of canela-preta, a strong and resistant wood, and the roof tiles were produced by slaves. But unlike other Bandeirista houses, Sítio da Ressaca did not have a chapel in a separate room, only a niche for the placement of the image of a saint.[17] The porch is fixed to the retaining wall.[16]

However, the Casa do Sítio da Ressaca has a peculiarity concerning the other examples of Bandeirista architecture in the city, which is the asymmetry of its plan, in which there is a single porch, not centralized, on the main façade and a gable roof. Antonio Cantarella, the last owner, who was also responsible for the urbanization of the Jabaquara neighborhood, transformed the site into a farm and divided it in 1969, the same year that the subway arrived in the region, which resulted in the expropriation of more than a third of the region to be used as a facility for the shunting yard.[18]

See also

References

- "O Bandeirismo | Resumo Escolar". www.resumoescolar.com.br. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- "Prefeitura de São Paulo".

- Ramalho, Nelson A. "Museu da Cidade de São Paulo". www.museudacidade.sp.gov.br. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- "Casa do Sítio da Ressaca e Entorno em São Paulo". www.areasverdesdascidades.com.br. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

- "Acervo da Memória e do Viver Afrobrasileiro no Jabaquara - SP - Encontra Jabaquara". www.encontrajabaquara.com.br. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- "Sítio da Ressaca". www.cidadedesaopaulo.com. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- "Museu da Cidade - Sítio da Ressaca".

- "MAYUMI, Lia. "Taipa, canela preta e concreto: um estudo sobre a restauração de casas bandeiristas em São Paulo". Tese de Doutorado. USP. 2006".

- "Casa do Sítio da Ressaca no Jabaquara - SP - Encontra Jabaquara". www.encontrajabaquara.com.br. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- "ANDRADE, Francisco de Carvalho Dias de. COSTA, Eduardo. "Arquitetura bandeirista na serra do itapeti: um caso interessante para o estudo da arquitetura colonial paulista". VII Encontro de História da Arte - UNICAMP, 2011" (PDF).

- "Processo de tombamento do Sítio da Ressaca" (PDF).

- "São Paulo Minha Cidade - Jabaquara".

- "Casa do Sítio da Ressaca e Entorno em São Paulo". www.areasverdesdascidades.com.br. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- "Zanettini, Paulo Eduardo. "Maloqueiros e seus palácios de barro: o cotidiano doméstico na Casa Bandeirista". Universidade de São Paulo, 2006".

- "Casa do Sítio da Ressaca e Entorno em São Paulo". www.areasverdesdascidades.com.br. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- "Casas Bandeiristas - Casa do Jabaquara".

- "Reportagem do Antena Paulista sobre Casa Sítio da Ressaca".

- Ramalho, Nelson A. "Museu da Cidade de São Paulo". www.museudacidade.sp.gov.br. Retrieved 2017-04-16.