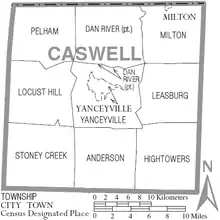

Caswell County, North Carolina

Caswell County is a county in the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is located in the Piedmont Triad region of the state. At the 2020 census, the population was 22,736.[1] Its county seat is Yanceyville.[2]

Caswell County | |

|---|---|

Old Caswell County Courthouse in Yanceyville | |

Seal | |

| Motto: "Preserving the Past - Embracing the Future" | |

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 36°24′00″N 79°19′48″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | June 1, 1777 |

| Named for | Richard Caswell |

| Seat | Yanceyville |

| Largest community | Yanceyville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 428.71 sq mi (1,110.4 km2) |

| • Land | 425.37 sq mi (1,101.7 km2) |

| • Water | 3.34 sq mi (8.7 km2) 0.78% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 22,736 |

| • Estimate (2022) | 22,614 |

| • Density | 53.45/sq mi (20.64/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional districts | 4th, 6th |

| Website | www |

Partially bordering the state of Virginia, the county was formed from Orange County in 1777 and named for Richard Caswell, the first governor of North Carolina.[3] Other Caswell County communities include Blanch, Casville, Leasburg, Milton, Pelham, Prospect Hill, Providence, and Semora.[4]

The Dan River flows through a portion of the county. Hyco Lake is a popular recreational area and key water source.[5]

History

Early history

The area was first inhabited by Native Americans over 10,000 years ago.[6] Indigenous residents were of Siouan groups, including the Occaneechi.[5] Abundant evidence of indigenous activity has been found in many parts of Caswell County.[7][8]

In 1663 and 1665, Charles I of England gave all of what is now North Carolina and South Carolina (named for him) to eight of his noblemen, the Lords Proprietors.[9] Caswell County was originally part of the land grant belonging to Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon.[10]

Colonial records show land grants in northern Orange County (later Caswell County) as early as 1748. There were Scotch-Irish, German, and English settlements along the Dan River and Hogans and Country Line creeks by 1751. The first recorded settlement occurred between 1750 and 1755 when eight to ten families migrated from Orange County and Culpeper, Virginia.[11] The primary reason for resettlement was economic. They were searching for fertile land, which the low land of the Dan River and several creeks provided.[10]

After the initial settlements, the area experienced rapid population growth. The free settlers who lived in the county before 1800 were mostly of English, Scotch-Irish, French Huguenot, and German descent.[10] Scotch-Irish and German families traversed the Great Wagon Road, which was the main route for settlement in the region, and had come by way of Virginia and Pennsylvania. English and Huguenot migrants came from settled areas of eastern North Carolina, following the Great Trading Path. English colonists also came from Virginia using the same network of roads and trails.[12] Enslaved Africans were brought to the area by slaveholders and slave-trading agents involved in speculation.[13][14] By 1800, enslaved persons accounted for nearly one-third (32%) of Caswell County's population.[10] As they grew in number, substantially so after 1790, they powered more and more of the area's agricultural and economic development.[15]

The settlers first consisted mainly of yeoman farmers and planters. Middle-class settlers arrived afterward in the 18th century and were called the "new families."[16][10] Scotch-Irish and English culture predominated in the area socially, spiritually, educationally, and economically.[17]

Yeoman farmers accounted for more than half the settler population.[10] Few if any were slaveholders at this time. The yeomanry owned small family farms and lived in log homes. They farmed for subsistence, with surpluses going toward debt settlement or bartering for goods. Relying on the skilled and unskilled labor of family members, neighbors, and others, they linked farms to early grist mills and sawmills.[12]

Middle-class families accounted for less than a fifth of the settler population and were chiefly involved in business entrepreneurship, craftsmanship, small-scale commercial farming, export, and trade.[13][10] They actively promoted business and settlement in and around towns such as Leasburg, Milton, and numerous villages to further local economic development and their own upward social mobility. As the area grew more populated and prosperous, a significant number of middle-class residents transitioned to the upper-middle class.[10]

The planter class constituted the upper class and were the smallest segment of the settler population. Most came from prosperous families and were well versed in the literature of the Enlightenment. Due to their social position, they deeply impacted the county economically, culturally, and politically.[18][10] The area's other planters, in contrast, were less prominent and wealthy than the gentry in their midst. They were common or smaller planters with less land and lived more ordinary upper-middle class lives.[19] Several had indentured servants or bound apprentices of mixed race.[20]

No matter their class distinction, planters were the most socioeconomically advantaged inhabitants. They traded commodities with other settlers and were involved in land speculation and the domestic slave trade. They founded mills, sold livestock, and grew profitable crops such as wheat, corn, and oats on farms or plantations.[21] Until the early 1800s, tobacco was harvested mainly as a secondary crop by the settlers depending on changing market demand, pricing, soil exhaustion, and other variables.[22]

During the colonial period from approximately 1761 until 1772, it was common for local planters to receive credit loans from British-owned mercantile companies in the province for the purpose of funding the expansion of agricultural production. The monies went toward purchases of additional land and enslaved labor. Such companies also supplied enslaved workers and consumer items to area planters and managed tobacco exports sent to Virginia warehouses.[23] Their merchants offered good tobacco prices initially but eventually reduced them greatly, causing many planters to fall into substantial debt, which could not be repaid without selling land or enslaved people. Due to the American Revolutionary War, most of these debts were never repaid. After the war, the demand for tobacco rose when new markets were found without such middlemen.[24]

Not long after they arrived, the settlers to the area had been progressive in building homes, starting businesses, and establishing churches. Prominent planters promoted a culture of education that later saw the creation of private academies in the early 1800s.[10] The older families were generally more politically and fiscally conservative than the newcomers. They usually voted against funds for postwar internal improvements and were not supportive of expenditures that raised the county debt due to an aversion to raising taxes and expanding the role of government.[10]

Before the Revolutionary War, the biggest threats to public safety and social stability in the region were the French and Indian War and the Regulator Movement in present Orange County.[25] While the movement increased class tensions within communities, the settlers came together in support of the American Revolution.[10]

Prior to the Revolution, the Church of England was the most common religious affiliation in the area.[10] Pennsylvania missionary Hugh McAden founded Red House Presbyterian Church possibly as early as 1755.[26][10] Country Line Primitive Baptist Church was established in 1772.[27] Lea's Chapel, a Methodist Episcopal church, was organized in 1779.[28]

Creation

Caswell County was formed from a portion of Orange County, effective June 1, 1777.[29] It was created so that governance could be more localized and efficient.[30] The county was named for Richard Caswell who was the first governor of North Carolina after the Declaration of Independence in 1776, a delegate at the First and Second Continental Congresses, and a senior officer of militia in the Southern theater of the Revolutionary War.[31] The legislative act creating Caswell ordered its first court to be held at the homestead of Thomas Douglas and appointed commissioners to find a permanent location to build a county courthouse and prison.[29]

During the prelude to the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in 1781, Lord Cornwallis pursued General Nathanael Greene through Caswell County. Greene's retreat, called the "Race to the Dan," was a calculated ploy. His objective was to extend Cornwallis far beyond his supply base in Camden, South Carolina so that his fighting power would be significantly diminished. Cornwallis and his troops marched through Camp Springs and Leasburg, which was the first county seat. They continued on to the Red House Church area of Semora.[10] It is unknown how many locally enslaved people fled to the British for safe haven before the Battle of Yorktown in 1781.[32]

By the war's end in 1783, Caswell County had made significant contributions in personnel and materiel to the war effort. Little fighting took place locally. County residents renowned for their Revolutionary War service include Lieutenant Colonel Henry "Hal" Dixon, John Herndon Graves, Dr. Lancelot Johnston, and Starling Gunn.[30] By that point no county courthouse had been built, so the General Assembly passed another act authorizing the county to erect public buildings. A courthouse was subsequently established at Leasburg, which was officially incorporated in 1788.[29]

After the war, a small number of free Black families moved to the area. Most of the men had served in the Continental Army or Navy.[33] Usually skilled in a trade, they farmed in a manner similar to yeoman farmers but did not have equal rights.[34]

In 1786, a special state census ranked Caswell County as the second-largest county with a population of 9,839. Halifax County had only 489 more inhabitants.[30]

Approximately six years later in 1792, the eastern half of the county became Person County. After the division, the seat of Caswell County's government was moved to a more central location. The community hosting the new county seat was originally called Caswell Court House. In 1833, the name was changed to Yanceyville.

Early 19th century to World War II

In the early 1800s, Caswell County's wealthy landowners were moving away from diversified farming and accelerating toward tobacco as a single cash crop. This agricultural conversion considerably affected the growth of the enslaved population, which rose 54 percent from 1800 to 1810.[10]

In 1810, the village of Caswell Court House (later Yanceyville) had one store and a hattery, two taverns, and approximately fifteen homes. silversmiths, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, coachmakers, and other tradesmen soon began opening businesses. Attorneys, doctors, preachers, and a number of politicians were also drawn to the growing village and county seat.[35]

Around 1830, the "Boom Era" began, which lasted until the American Civil War. During this period, the county saw the creation of new flour and lumber mills and experienced the furniture output of Thomas Day, a free Black businessman in Milton. A cotton factory, foundry, and silk company were also in operation. In Yanceyville, roads were improved and given names by 1841. The town became wealthy enough by 1852 to charter an independent bank, the Bank of Yanceyville, whose market capitalization ranked among the highest in the state.[35]

_20_dollars_1856_urn-3_HBS.Baker.AC_1141665.jpeg.webp)

In 1839, on Abisha Slade's farm in Purley, an enslaved man named Stephen discovered the bright leaf tobacco flue-curing process.[36][30] Slade perfected the curing method in 1856. The following year his farm harvested 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) of bright leaf tobacco on 100 acres of land and the crop was sold in Lynchburg, Virginia at an exorbitant price. Slade taught the flue-curing technique to many farmers in the area and elsewhere. Bright leaf tobacco became popular with smokers and North Carolina growers gained a dominant position in the tobacco industry as a result.[37]

The tobacco economy, and the industries supported by it, enriched many locals. The lifestyle of many yeoman farmers changed into that of planters.[10] The newly wealthy built impressive homes and sent their children to private academies.[30] However, the majority of Caswell County's inhabitants did not benefit. In 1850, enslaved African Americans accounted for 52 percent of the county's population.[38]

By 1856, tobacco overshadowed all other forms of enterprise in Caswell County. Tobacco warehouses and manufacturing & processing plants dotted the skyline, with the largest centers located in Yanceyville and Milton.[10] The growth of the industry and increase in raw tobacco production created an expanding need for labor. The number of enslaved people grew to 9,355 in 1860, from a total of 4,299 in 1810 and 2,788 in 1800.[10]

There were 26 free Black inhabitants residing in Caswell County in 1800, 90 in 1810, and 282 in 1860. The white population declined from a peak of 8,399 in 1850 to 6,578 in 1860. This was due to the western migration of small-scale farmers who were unable to compete with the larger tobacco planters.[10]

In 1858, at the tail end of the opulent Boom Era, construction began on Caswell County Courthouse. Built using enslaved labor, it was completed in 1861 during the onset of the Civil War.[39][40]

After the war, the county continued its economic dependence on tobacco and was averse to agricultural diversification. The Second Industrial Revolution in varying degrees passed it by. Other than a few tobacco mills, there was an absence of industry and no railroad.[30] The population significantly diminished until 1910 when it began to increase.[41] By then, Yanceyville and Semora had phone service.[42]

The county's population kept growing through the 1920s. To provide better public facilities, the Caswell County Board of Education initiated school improvement projects.[43] During this time in 1926, The Caswell Messenger began publication.[44]

In 1937, the Yanceyville Rotary Club was founded and members successfully pioneered economic and community development projects.[17] Roosevelt's New Deal programs during the Depression years, improved farming techniques starting in the 1940s, and the economic impact of World War II also contributed significantly to revitalizing the area.[35][30]

Post–World War II to early 21st century

After World War II, as Caswell County and the world returned to civilian life, it became evident that new efforts were needed to overcome old economic barriers. In the 1950s and 1960s, county leaders saw the world in a new way due to their military service, realizing the need for proactivity in securing a better future for residents. They understood the county's future depended on the development of water resources sufficient for industrial expansion as well as the need to improve infrastructure such as roads, provide new and various county-wide services, increase cultural resources, and operate local government in a business-like fashion.[45] The history of Caswell County in the second half of the 20th century is characterized by much progress in these areas, but critical needs remained. The heritage of the county's earlier Boom Era of bright leaf tobacco and Greek Revival architecture represented both an opportunity and a hindrance.[45]

By 1950, Caswell County reached a peak of 20,870 inhabitants, which was not surpassed until the 2000 census.[46] The economic upswing of the 1950s saw new businesses entering the area. This included the opening of a meatpacking operation in 1956 in the county's southwest corner. Between the mid-1950s and mid-1980s, the county also attracted textile mills to Yanceyville.[47] Such growth enabled the local government to broaden its tax base and see increases in public revenue.[30]

As the county entered the 21st century, it faced the aftermath of a crisis in the tobacco industry, the urgent need for economic development in light of the Information Age, and a national trend toward heritage tourism as a means of economic growth.[48] Caswell County's economy continued to develop, diversify, and experience growth away from tobacco production. Business and entrepreneurial activity increased due to the area's location, commercial properties, land primed for development, relatively low property tax rate, and other factors.[48][49]

Civil War period

In May 1861, North Carolina with some reluctance joined the Confederacy, which by then was at war with the Union.[50][51] Caswell County provided troops, clothing, food, and tobacco in support of the war effort. Companies A, C, and D of the North Carolina Thirteenth Regiment consisted almost entirely of county enlistments. The area's soldiers fought in every major Civil War battle and there were many casualties.[52][10]

In Caswell County in January 1862, a significant number of African Americans fled slavery. Seven patrol squads comprising 34 individuals were dispatched to Yanceyville in search of them.[52] It is unknown if any were able to find safe haven behind Union lines.

In the spring of 1862, salt used for meat preservation was rationed, which was a statewide measure. As the war raged on, the county's inhabitants faced food shortages. Daily necessities were in short supply. Speculators benefitted while most remained in need.[52]

The minutes of the Caswell County Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions from January 1863 to July 1866 were either lost or destroyed. Consequently, it is difficult for researchers to ascertain what was occurring in the county's court system during this period.[52]

At the 1860 U.S. census, 58.7 percent of Caswell County's population was enslaved.[53] Due to the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, enslaved African Americans in Confederate territory were recognized as free individuals by the executive branch of the U.S. federal government. They gained military protection upon crossing into Union-controlled areas or through the advance of federal troops.[54]

Many African Americans likely either fled or attempted to flee the area between 1863 and the war's end. Most remained confined behind Confederate lines until Union forces occupied much of the state during the Carolinas campaign in 1865.[50]

Reconstruction era

After the Civil War during Reconstruction, the pattern of daily life in Caswell County dramatically changed. The previous plantation way of life had disappeared. Small farmers fell into deeper poverty. Abandoned land and eroded soil permeated the landscape. The area faced a decreased standard of living and insufficient public revenue for services that governments ordinarily provided.[10]

Many whites in the county resented the war's outcome as did others in the North Carolina Piedmont area. Regional newspapers actively fomented their bitterness. When Congressional Reconstruction was established in 1867,[55] a large segment of residents characterized it as an effort by Radical Republicans to force Black suffrage upon them. A significant number began flocking to the Conservative Party, which was a coalition of the prewar Democratic Party and old-line Whigs.[56]

African Americans in the area had experienced immense jubilation when informed of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Their freedom was then safeguarded by Union troops, the Freedmen's Bureau, and the protection of the Thirteenth Amendment. However, in 1866 restrictive state laws called "Black Codes" were passed in North Carolina by former Confederate legislators who had returned to power as Conservatives.[57] Enacted to regain control over African Americans, these laws were nullified by congressional civil rights legislation later in 1866.[58]

In 1868 and 1869, the Republican-controlled General Assembly ratified the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments respectively.[59] Ensuring the right to vote regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, the Fifteenth Amendment became a part of the U.S. Constitution in February 1870.[60] In that year's U.S. census, African Americans represented approximately 59 percent of Caswell County's population.[61] Over a span of five years from 1865 to 1870, they had gained constitutional protection from slavery and voting rights. They could seek employment, use public accommodations, acquire land, and participate in the political process.[62]

In January 1868, thirteen African American delegates representing 19 majority-Black counties attended the state's constitutional convention in Raleigh. They were North Carolina's first Black Caucus. Their members included a Republican legislator from Caswell County named Wilson Carey. At the convention, he spoke out against Conservative proposals to attract white immigrants to North Carolina. Carey felt the focus should instead be on African American North Carolinians who had built up the state.[63]

The 1868 constitutional convention passed resolutions that included the abolition of slavery, the adoption of universal male suffrage, the removal of property and religious qualifications for voting and office holding, and the establishment of a uniform public school system. Because the convention gave North Carolina a new constitution in 1868 that protected the rights of African Americans, the state was readmitted to the Union that same year on July 4 upon ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.[64]

Enfranchising African Americans with the right to vote in elections was anathema to county and statewide Conservative Party members. This was not only due to their white supremacy but also because it threatened their power. Their animosity toward white and Black Republicans had begun to skyrocket when Republican gubernatorial candidate William W. Holden endorsed universal male suffrage at the party's state convention in March 1867.[56] The suffrage resolution's passage and Holden's victory in 1868 substantially added to the continuing friction. This growing tension helped make Caswell County and the region a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity that same year. African Americans and their supporters in the area were subsequently subjected to a heinous campaign of violence, intimidation, and murder to prevent them from voting.[56]

As Klan violence in Caswell County escalated in 1870, the Republican state senator of the area, John W. Stephens, became increasingly fearful of attack.[65] On May 21, he went to the courthouse in Yanceyville to convince the former Democratic county sheriff, Frank A. Wiley, to seek re-election as a Republican with his support and thus achieve a political reconciliation in the county.[66] Wiley had secretly agreed to work with the Klan and lured Stephens into a trap, whereby he was choked with a rope and stabbed to death by Klansmen in a vacant courthouse room. The current sheriff, Jessie C. Griffith, himself a Klansman and prominent Conservative, made little effort to investigate the assassination.[67]

Holden was disgusted by the murder of Stephens.[68] Conferring with his advisers, he decided to raise a militia to combat the Klan in Caswell and nearby Alamance County.[69] On July 8, he declared Caswell County to be in a state of insurrection.[70] About 350 militiamen, led by Colonel George Washington Kirk, arrived on July 18 and established headquarters in Yanceyville.[71] The militia arrested 19 men in the county as well as several dozen more in Alamance County, and Klan activities in both counties promptly ceased.[72] The prisoners were initially denied habeas corpus before being turned over to local courts, which did not convict any of the accused.[73] On November 10, Holden declared that there was no longer a state of insurrection in Alamance and Caswell counties.[74]

In December 1870, the state legislature, which had a Conservative majority that had come into power on the heels of the political backlash they had spearheaded against Holden over the incident, impeached him on eight charges. He was convicted on six of them and removed from office in March 1871. Holden's departure severely weakened the Republican Party in the state.[56]

The Conservative Party proceeded to institute white supremacy in state government in 1876.[64] They dropped the name "Conservative" that same year to become the Democratic Party of North Carolina.[75] When federal troops left the next year, ending Reconstruction, the stage was set for the passage of Jim Crow laws.[64]

Civil rights movement

By the end of the 1960s, Caswell County's public schools were beginning to fully integrate. A decade and a half earlier in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. In a later decision by the Court in May 1955 known as Brown II, school districts were given the ambiguous order to desegregate "with all deliberate speed."[76] Like many school boards in the South at the time, the Caswell County Board of Education interpreted the Court's ambiguity in a manner that served to delay, obstruct, and slow the process of racially integrating its schools.[77][78]

The Board of Education's resistance to integration had already been emboldened by North Carolina's passage of the Pupil Assignment Act in April 1955. The legislation gave county school boards full school placement authority.[78] Driven by the act's power, the Pearshall Plan's passage, and the prevailing anti-integration sentiment of the white community, the school district kept assigning children to schools in a segregated manner.[79]

In response to these developments, fifteen local African American parents presented a petition to the school district in August 1956 calling for the abolition of segregation, which the board refused to consider. Undeterred, the parents organized protests that included the NAACP. A federal lawsuit was subsequently filed in December 1956 asking for the immediate desegregation of Caswell County and North Carolina schools.[80]

In August 1957, 43 local students, many of whom were plaintiffs via their parents in the federal court case, applied for admission to public schools that were closer to their homes than the segregated ones they had been assigned.[81] The school board denied their applications and continued to reject them through 1962.[79] Nevertheless, the federal lawsuit kept moving forward.[82]

In December 1961, U.S. District Court Judge Edwin M. Stanley ruled that two brothers, Charlie and Fred Saunders, could promptly attend Archibald Murphey Elementary School, a now-closed formerly all-white school near Milton. When the new semester began in January, however, they did not present themselves for enrollment. The Ku Klux Klan had sent a threatening letter to the Saunders family previously.[83] According to an affidavit submitted by the children's father C.H. Saunders Sr., the KKK's threats caused him to miss a school board reassignment hearing ordered by the judge in August 1961 prior to his final judgment. Saunders also conveyed that he would be agreeable to transferring schools if his children's protection at Murphey Elementary could be assured.[83]

A year after the Saunders decision, Stanley ruled that the school district had been improperly administering the Pupil Assignment Act. In December 1962, he told the school boards of Caswell County and the city of Durham to allow every schoolchild complete freedom of choice regarding school placement.[84] On January 22, 1963, sixteen African American schoolchildren enrolled in four of the county's previously all-white schools.[79]

On their first day of school, a group of white men harassed and threatened one of the parents, Jasper Brown, who was a local civil rights leader and farmer. He was pursued and menaced by the men as he drove home. After a rear-end collision, the other vehicle's driver emerged with a firearm. Fearing for his life, Brown shot and wounded two of the men in an exchange of fire before turning himself in to police.[85][79] Due to the circumstances, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy was soon informed of the incident.[86]

Several months later, Brown was convicted of assault with a deadly weapon and served 90 days in jail. While awaiting trial, white men bombed his yard.[87] His four children and the 12 others who integrated the county's schools were physically threatened and emotionally abused throughout the semester. Despite requests from the NAACP and concerned families, no police protection was provided. Furthermore, the Board of Education refused to arrange school bus transportation.[88][79]

By late 1967, only 57 African American children out of a Black student population of approximately 3,000 were attending integrated public schools in Caswell County.[89][79] While there had been some faculty integration, the less than two percent enrollment rate in essence preserved segregation. The school district's integration plan had not fostered sufficient desegregation.[90] Its "freedom of choice" plan put the onus of integration on individual African American students and parents, who had to opt to cross the color line themselves.[90] If they did so, they faced social stigma, severe discrimination, and other hardships. Consequently, many families, though supportive of integration efforts, chose to keep their children safe in valued Black schools such as Caswell County High School.[91][79]

The school district's low integration rate resulted in the U.S. Office of Education citing the county in 1966 as one of seven in the state that were not in compliance with its civil rights Title IV guidelines. The bureau began taking steps to cut off federal funding.[92] The school district was not in full compliance with federal integration standards until 1969.[93] In that year, the Caswell County Board of Education implemented a plan for complete desegregation after Judge Stanley ordered the school district in August 1968 to integrate starting in the 1969–1970 school year.[94][95][79]

When school integration and consolidation subsequently occurred, Bartlett Yancey High School in Yanceyville became the only public high school in the county after Caswell County High School's closure in 1969.[96] The closed high school building's educational use was promptly reconfigured. The new integrated school was named N.L. Dillard Junior High School in honor of the former high school's principal. Integrated elementary schools were established based on zoning.[93]

Political leaders

Caswell County has produced notable political leaders throughout its history. Such politicians include Donna Edwards, Archibald Debow Murphey, Romulus Mitchell Saunders, and Bartlett Yancey, Jr.[97][98][99][100]

Legislators from the county had considerable influence on state politics during the first half of the 19th century.[30] Bartlett Yancey was speaker of the North Carolina Senate from 1817 to 1827. Romulus Mitchell Saunders was concurrently speaker of the North Carolina House of Commons from 1819 to 1820.[101]

Archibald D. Murphey has been called the "Father of Education" in North Carolina. Serving as a state senator, he proposed a publicly financed system of education in 1817. Murphey also made proposals regarding internal improvements and constitutional reform.[102]

Donna Edwards is a former U.S. congresswoman. Before entering Congress, she was the executive director of the National Network to End Domestic Violence, which provides advocacy and legal support to battered women. She worked to pass the Violence Against Women Act of 1994. In 2015, Edwards and other members of Congress introduced the Restoring Education and Learning Act (REAL Act) to reinstate Pell Grants to prisoners.[103]

Depiction in the arts

Writers including Alex Haley and artists such as Maud Gatewood have commented on Caswell County's history in their work. The county was briefly referenced in Haley's 1977 television miniseries Roots. It was cited as the location of champion cock fighter Tom Moore's (Chuck Connors) plantation.[104] When Gatewood designed the county seal in 1974, she added two large tobacco leaves as a symbol of the crop's long prominence in the area.[105]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 428.71 square miles (1,110.4 km2), of which 425.37 square miles (1,101.7 km2) is land and 3.34 square miles (8.7 km2) (0.78%) is water.[106] It is bordered by Person, Orange, Alamance, and Rockingham counties, and the state of Virginia.[107] The Dan River flows through a part of the county. Hyco Lake is an important water source and popular recreational site.[5]

For a comprehensive overview of Caswell County's geography see When the Past Refused to Die: A History of Caswell County North Carolina 1777–1977, by William S. Powell (1977) at 1–22.[108]

State and local protected areas

- Animal Park at the Conservators Center

- R. Wayne Bailey-Caswell Game Land[109]

Major water bodies

- Country Line Creek[110]

- Dan River

- S.R. Farmer Lake[111]

- Hogans Creek[112]

- Hyco Creek

- Hyco Lake

- Lynch Creek

- Moon Creek[113]

- North Fork Rattlesnake Creek[114]

- South Hyco Creek

- Sugartree Creek

- Wildwood Lake[115]

Adjacent counties

- Person County – east

- Orange County – southeast

- Alamance County – south

- Rockingham County – west

- Pittsylvania County, Virginia – north

- Halifax County, Virginia – north

- Danville, Virginia (independent city) – north

Infrastructure

Utilities

- Caswell County's electric system is maintained by Duke Energy and Piedmont Electric Cooperative.[116]

- Telephone network: CenturyLink

- Wireless networks: AT&T Mobility, U.S. Cellular, and Verizon Wireless

- Broadband internet: CenturyLink and Comcast

- Cable television: Comcast

Transportation

_entering_Caswell_County%252C_North_Carolina_from_Danville%252C_Virginia.jpg.webp)

Major highways

Interstate 40 and Interstate 85 are the closest interstate highways to the county, located 14 miles (23 km) south in Graham. When I-785 is completed, it will run through Caswell County near Pelham.[117]

Airports

- Yanceyville Municipal Airport[118]

- Danville Regional Airport, located 15.3 miles (25 km) north of Yanceyville

- Person County Airport, located 26.2 miles (42 km) southeast of Yanceyville

- Burlington-Alamance Regional Airport, located 29.4 miles (47 km) southwest of Yanceyville

- Piedmont Triad International Airport, located 46.5 miles (75 km) southwest of Yanceyville

- Raleigh-Durham International Airport, located 56 miles (90 km) southeast of Yanceyville

Railroad

Danville Amtrak station, located 13.9 miles (22 km) north of Yanceyville[119]

Public transit

- Caswell County Area Transportation System (CATS)[120]

Other

- Caswell Correctional Center, a medium custody facility of the North Carolina Department of Adult Correction[121]

- Dan River Prison Work Farm, a minimum custody facility of the North Carolina Department of Public Safety[122]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 10,096 | — | |

| 1800 | 8,701 | −13.8% | |

| 1810 | 11,757 | 35.1% | |

| 1820 | 13,253 | 12.7% | |

| 1830 | 15,185 | 14.6% | |

| 1840 | 14,693 | −3.2% | |

| 1850 | 15,269 | 3.9% | |

| 1860 | 16,215 | 6.2% | |

| 1870 | 16,081 | −0.8% | |

| 1880 | 17,825 | 10.8% | |

| 1890 | 16,028 | −10.1% | |

| 1900 | 15,028 | −6.2% | |

| 1910 | 14,858 | −1.1% | |

| 1920 | 15,759 | 6.1% | |

| 1930 | 18,214 | 15.6% | |

| 1940 | 20,032 | 10.0% | |

| 1950 | 20,870 | 4.2% | |

| 1960 | 19,912 | −4.6% | |

| 1970 | 19,055 | −4.3% | |

| 1980 | 20,705 | 8.7% | |

| 1990 | 20,693 | −0.1% | |

| 2000 | 23,501 | 13.6% | |

| 2010 | 23,719 | 0.9% | |

| 2020 | 22,736 | −4.1% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 22,614 | [1] | −0.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[123] 1790–1960[124] 1900–1990[41] 1990–2000[125] 2010[126] 2020[1] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 14,036 | 61.73% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 6,804 | 29.93% |

| Native American | 65 | 0.29% |

| Asian | 61 | 0.27% |

| Pacific Islander | 13 | 0.06% |

| Other/Mixed | 755 | 3.32% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,002 | 4.41% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 22,736 people and an estimated 8,993 households and 6,186 families residing in the county. In 2020, the estimated median age was 46.2 years. For every 100 females, there were an estimated 101.9 males.[127]

2010 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 14,513 | 61.19% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 7,991 | 33.69% |

| Native American | 70 | 0.30% |

| Asian | 60 | 0.25% |

| Pacific Islander | 4 | 0.02% |

| Other/Mixed | 337 | 1.42% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 744 | 3.14% |

At the 2010 census, there were 23,719 people and an estimated 8,788 households and 6,345 families residing in Caswell County.[128] In 2010, the estimated median age was 42.8 years. For every 100 females, there were an estimated 103.7 males.[129]

2000 census

At the 2000 census,[130] there were 23,501 people and an estimated 8,670 households and 6,398 families residing in the county. The population density was 55 people per square mile (21 people/km2). There were 9,601 housing units at an average density of 23 units per square mile (8.9 units/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 61.07% White, 36.52% African American, 1.77% Hispanic or Latino, 0.19% Native American, 0.15% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 1.17% from other races, and 0.86% from two or more races.

Out of the 8,670 households, 31.00% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.20% were married couples living together, 14.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.20% were non-families. 23.20% of all households consisted of individuals living alone and 10.20% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.56 and the average family size was 3.01.

The age distribution of the county's population consisted of 23.20% under the age of 18, 7.70% from 18 to 24, 30.10% from 25 to 44, 26.00% from 45 to 64, and 13.00% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 102.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 102.30 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $35,018 and the median income for a family was $41,905. Males had a median income of $28,968 versus $22,339 for females. The per capita income for the county was $16,470. About 10.90% of families and 14.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.30% of those under age 18 and 21.10% of those age 65 and over.

Government and politics

Seated in Yanceyville, Caswell County's government consists of 28 departments, an elected board of commissioners, a clerk to the board, and an appointed county manager.[131] The county has additional central administration, Cooperative Extension, E-911, and Juvenile Crime Prevention Council staff.[132] Caswell County is a member of the Piedmont Triad Council of Governments.[133] The county lies within the bounds of the 22nd Prosecutorial District, the 17A Superior Court District, and the 17A District Court District.[134]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 7,089 | 58.82% | 4,860 | 40.33% | 102 | 0.85% |

| 2016 | 6,026 | 54.44% | 4,792 | 43.29% | 252 | 2.28% |

| 2012 | 5,594 | 50.67% | 5,348 | 48.45% | 97 | 0.88% |

| 2008 | 5,208 | 47.95% | 5,545 | 51.05% | 109 | 1.00% |

| 2004 | 4,868 | 51.58% | 4,539 | 48.10% | 30 | 0.32% |

| 2000 | 4,270 | 50.70% | 4,091 | 48.58% | 61 | 0.72% |

| 1996 | 3,310 | 40.57% | 4,312 | 52.86% | 536 | 6.57% |

| 1992 | 2,793 | 33.40% | 4,725 | 56.50% | 845 | 10.10% |

| 1988 | 3,299 | 43.93% | 4,189 | 55.79% | 21 | 0.28% |

| 1984 | 3,992 | 48.84% | 4,157 | 50.86% | 25 | 0.31% |

| 1980 | 2,156 | 37.32% | 3,529 | 61.09% | 92 | 1.59% |

| 1976 | 1,761 | 32.08% | 3,707 | 67.54% | 21 | 0.38% |

| 1972 | 2,983 | 59.65% | 1,922 | 38.43% | 96 | 1.92% |

| 1968 | 1,036 | 17.20% | 2,137 | 35.47% | 2,851 | 47.33% |

| 1964 | 1,793 | 41.64% | 2,513 | 58.36% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 1,272 | 30.99% | 2,832 | 69.01% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 1,204 | 32.79% | 2,468 | 67.21% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 973 | 27.25% | 2,597 | 72.75% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 351 | 14.63% | 1,651 | 68.82% | 397 | 16.55% |

| 1944 | 492 | 20.37% | 1,923 | 79.63% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 351 | 13.07% | 2,335 | 86.93% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 207 | 7.67% | 2,493 | 92.33% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1932 | 169 | 8.31% | 1,858 | 91.39% | 6 | 0.30% |

| 1928 | 749 | 44.45% | 936 | 55.55% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 467 | 30.21% | 1,075 | 69.53% | 4 | 0.26% |

| 1920 | 505 | 28.96% | 1,239 | 71.04% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1916 | 338 | 28.48% | 849 | 71.52% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1912 | 154 | 17.04% | 705 | 77.99% | 45 | 4.98% |

Elected officials

In January 2022, Caswell County's elected officials were:[136][137][138]

- Tony Durden, Jr. (D), Caswell County Sheriff

- John Satterfield (D), Caswell County Clerk of Courts

- Ginny S. Mitchell (D), Caswell County Register of Deeds

Caswell County Board of Commissioners:

- Jeremiah Jefferies (D)

- Nathaniel Hall (D)

- William E. Carter (D)

- Rick McVey (R), (chairman)

- David Owen (R), (Vice Chair)

- Steve Oestreicher (R)

- John D. Dickerson (R)

North Carolina General Assembly representatives:

- Senate: Graig R. Meyer (D-23rd)

- House: Renee Price (D-50th)

U.S. House of Representatives:

- Valerie Foushee (D-4th)

- Kathy Manning (D-6th)

Economy

The economy of Caswell County is rooted in agriculture, which continues to develop and experience growth away from tobacco cultivation. The area's location, commercial properties, land primed for development, and relatively low property tax rate have contributed to an increase in business activity and entrepreneurship.[139][49]

Caswell County's agricultural sector produces hemp, tobacco, soybeans, corn, wheat, oats, barley, hay, alfalfa, beef cattle, sheep, swine, and poultry. The county also produces minerals such as soapstone, graphite, mica, corundum, microcline, and beryl. Manufactured goods include textiles, clothing, and electronics.[140][5]

NC Cooperative Extension in Yanceyville connects local agribusinesses and farmers with crucial research-based information and technology.[141] The Caswell County Local Foods Council manages the Caswell Farmers' Market in Yanceyville and initiates community-driven projects.[142]

The county is home to two industrial parks: Pelham Industrial Park in Pelham and Caswell County Industrial Park in Yanceyville.[143] CoSquare, a coworking space that offers several business possibilities for entrepreneurs, is located in Yanceyville's downtown historic district.[144] The largest industries in Yanceyville are accommodation and food services, health care and social assistance, and manufacturing.[145]

Caswell County benefits from its proximity to the greater Piedmont Triad area, Danville, Virginia, and the Research Triangle. Residents have access to a host of goods, services, attractions, and employment in the region.[146] The county receives economic activity in kind from these neighboring areas.[48]

Education

Higher education

- Piedmont Community College's satellite campus in Caswell County is located in Yanceyville.[147]

Primary and secondary education

The Caswell County public school system has six schools ranging from pre-kindergarten to twelfth grade. The school district operates one high school, one middle school, and four elementary schools:[148]

- Bartlett Yancey High School

- N.L. Dillard Middle School

- North Elementary School

- Oakwood Elementary School

- South Elementary School

- Stoney Creek Elementary School

Healthcare

Health care providers in Caswell County include:

Parks and recreation

Caswell County's outdoor recreational areas include:[153][154][155]

- Animal Park at the Conservators Center (in Anderson township)

- The Dan River (in Milton)

- Hyco Lake (near Semora)

- Person Caswell Recreation Park (near Semora)

- Maud F. Gatewood Municipal Park (in Yanceyville)

- S.R. Farmer Lake (in Yanceyville township)

- Cherokee Scout Reservation's Boy Scouts of America camp (near S.R. Farmer Lake)

- Yanceyville Park/Memorial Park (in Yanceyville)

- Caswell Community Arboretum (in Yanceyville)

- Caswell County Parks & Recreation Center (in Yanceyville)

- Caswell Pines Golf Club (in Yanceyville township)

- Caswell Game Land (near Yanceyville)

- Country Line Creek (in Caswell Game Land)

- Hyco Creek (in Caswell Game Land)

Indoor and outdoor recreational facilities, as well as sports programs and activities, are offered by the Caswell County Department of Parks & Recreation.[155] The Caswell Senior Center, which is located in Yanceyville, has recreation and fitness facilities built in 2009.[156]

Arts and culture

Caswell County hosts two major festivals a year: the "Bright Leaf Hoedown" and the "Spring Fling."[157] The Bright Leaf Hoedown is a one-day outdoor festival held in late September in downtown Yanceyville. It features local food vendors, live entertainment, crafts, and non-profit organizations, usually drawing more than 5,000 guests.[158][159] The Spring Fling is a two-day event and is held on a weekend in late April or early May on the grounds of the Providence Volunteer Fire Department.[160]

The Caswell County Historical Association hosts its annual Heritage Festival in Yanceyville every May. The festival celebrates county history through tours, living history reenactments, games, vendors, and live music.[161]

Downtown Yanceyville's historic district features an antebellum courthouse designed by William Percival and several other examples of antebellum architecture. The Yanceyville Historic District, Bartlett Yancey House, John Johnston House, William Henry and Sarah Holderness House, Melrose/Williamson House, Graves House, and Poteat House are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[162][163]

Warren House and Warren's Store in Prospect Hill and the Garland-Buford House and James Malone House near Leasburg are also listed on the National Register of Historic Places in addition to Wildwood near Semora and Woodside near Milton.[164]

Caswell County's cultural attractions also include:[165][166][167][168][5]

- Caswell Council for the Arts (in Yanceyville)

- Caswell County Civic Center (in Yanceyville)

- Caswell County Veterans Memorial (in Yanceyville)

- Caswell Farmers' Market (in Yanceyville)

- Caswell Horticulture Club

- Gunn Memorial Public Library (in Yanceyville)

- Historic Caswell County Jail (in Yanceyville)

- Milton Historic District

- Milton Renaissance Foundation Museum & Visitors Center

- Milton Studio Art Gallery

- Piedmont Triad Visitor Center (in Pelham)

- Old Poteat School/Poteat One-Room School (in Yanceyville)

- Red House Presbyterian Church (in Semora)

- Richmond-Miles History Museum (in Yanceyville)

- Shangri-La Miniature Stone Village (in Prospect Hill)

- Thomas Day House and Union Tavern (in Milton)

- Town of Yanceyville Public Safety Memorial

- Yanceyville Museum of Art

- Yanceyville Pavilion

- Yanceyville's municipal water tower

- Yoder's Country Market (in Yanceyville)

The Caswell County Civic Center in Yanceyville has a full-size professionally equipped stage, a 912-seat auditorium, and meeting and banquet facilities for up to 500. The Civic Center also has accessories for concerts, theatre, and social functions as well as a lobby art gallery.[169]

Gunn Memorial Public Library in Yanceyville conducts summer reading programs for children of all ages.[170]

Communities

Towns

- Milton

- Yanceyville (county seat and largest community)

Unincorporated communities

- Blanch

- Camp Springs

- Casville

- Cherry Grove

- Estelle

- Fitch

- Frogsboro

- Hightowers

- Jericho

- Leasburg

- Milesville

- Osmond

- Pelham

- Prospect Hill

- Providence

- Purley

- Quick

- Semora

- Stony Creek

Notable people

Academia

- A. Oveta Fuller (1955-2022), associate professor of microbiology at University of Michigan Medical School[171]

- Henry Lee Graves (1813–1881), president of Baylor University

- William Louis Poteat (1856–1938), professor of biology and president of Wake Forest University, public intellectual, early advocate of Darwinian evolution

- Henry Roland Totten (1892–1974), botanist[172]

Art, literature, and music

- Max Drake (born 1952), musician

- Maud Gatewood (1934–2004), artist

- Mel Melton, musician[173]

- Ida Isabella Poteat (1858–1940), artist and instructor

- Moses Roper (1815–1891), African American abolitionist, author, and orator

- Ray Scott (born 1969), country music artist

- Carolina Slim (1923–1953), Piedmont blues guitarist and singer

- Hazel Smith (1934–2018), country music journalist, publicist, singer-songwriter, television and radio show host, and cookbook author

- The Badgett Sisters, folk and gospel group composed of sisters Celester, Connie, and Cleonia Badgett

Athletes

- Mic'hael Brooks (born 1991), former NFL player who attended high school in Yanceyville

- John Gunn (1939–2010), race car driver[174]

- Lee Pulliam (born 1988), stock car racing driver and team owner

- Neal Watlington (1922–2019), MLB player for the Philadelphia Athletics[175]

- Carl Willis (born 1960), former MLB player and current pitching coach for the Cleveland Guardians[176]

Business

- Thomas Day (1801–1861), free Black furniture craftsman and cabinetmaker

- Edmund Richardson (1818–1886), entrepreneur who produced and marketed cotton

- Samuel Simeon Fels (1860–1950), businessman and philanthropist

Government and law

- Bedford Brown (1795–1870), U.S. senator

- Richard Caswell (1729–1789), first and fifth governor of North Carolina

- Archibald Dixon (1802–1876), U.S. senator

- Donna Edwards (born 1958), former U.S. representative

- Calvin Graves (1804–1877), house member of the North Carolina General Assembly and member of the North Carolina Senate

- John Kerr Hendrick (1849–1921), U.S. representative

- Louisa Moore Holt (1833–1899), First Lady of North Carolina

- John Kerr (1782–1842), member of the U.S. House of Representatives

- John Kerr Jr. (1811–1879), congressional representative and jurist

- John H. Kerr (1873–1958), jurist and politician

- Benjamin J. Lea (1833–1894), lawyer and politician who served as a justice on the Tennessee Supreme Court

- Jacob E. Long (1880–1955), 15th lieutenant governor of North Carolina from 1925 to 1929 serving under Governor Angus W. McLean

- Giles Mebane (1809–1899), speaker of the North Carolina Senate during most of the Civil War[177]

- Anderson Mitchell (1800–1876), U.S. representative[178]

- Archibald Debow Murphey (1777–1832), attorney, jurist, and politician who was known as the "Father of Education" in North Carolina

- Romulus Mitchell Saunders (1791–1867), U.S. representative

- John W. Stephens (1834–1870), North Carolina state senator, agent for the Freedmen's Bureau

- Jacob Thompson (1810–1885), U.S. secretary of the interior

- Hugh Webster (1943–2022), register of deeds for Alamance County and North Carolina state senator[179]

- Marmaduke Williams (1774–1850), Democratic-Republican U.S. congressman

- George “Royal George” Williamson (1788–1856), member of the North Carolina Senate

- Bartlett Yancey, Jr. (1785–1828), Democrat-Republican U.S. congressman

Miscellaneous

- Oscar Penn Fitzgerald (1829–1911), Methodist clergyman, journalist, and educator

- Henrietta Phelps Jeffries (1857–1926), African American midwife and a founding member of Macedonia AME Church in Milton

- Peter U. Murphey (1810–1876), naval officer and captain of the CSS Selma during the Civil War

See also

- List of counties in North Carolina

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Caswell County, North Carolina

- Haw River Valley AVA, wine region partially located in the county

- Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, state-recognized tribe that resides in the county

- Virginia International Raceway, a nearby multi-purpose road course offering auto and motorcycle racing

References

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Caswell County, North Carolina". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Caswell County, North Carolina". www.carolana.com. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- "Our Towns". www.allincaswellnc.com. Retrieved December 20, 2022.

- Powell, William S. (2006). "Caswell County". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- Claggett, Stephen R. "North Carolina's First Colonists: 12,000 Years Before Roanoke". North Carolina Office of State Archeology. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- "Caswell County History Website – American Indian Heritage". NCCCHA.org. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- Powell 1977, p. 28-31.

- "Lords Proprietors". Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- "Caswell County: The First Century, 1777–1877" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- George Washington was Culpeper County's surveyor from 1749 to 1750.

- "History and Architecture of Orange County, North Carolina" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- "Settlement of the Piedmont, 1730–1775". Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- "Patterns in the intercolonial slave trade across the Americas before the nineteenth century". Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "The Growth of Slavery in North Carolina". Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- "The Evolution of Gentility in Eighteenth-century England and Colonial Virginia" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- "Caswell is Home of Flue-Cured Tobacco," The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), May 18, 1940, p11

- "Gentry". Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "The North Carolina Historical Review". Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "Davis Family". Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- "Plantations of North Carolina". Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- "Soil Survey of Caswell County, North Carolina" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- "Scotch Merchants". Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "Tobacco & Colonial American Economy". Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- "Regulator Movement". Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- "McAden, Hugh". NCPedia.org. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- "Historical Sketch of Country Line Church" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- "Chapel on South Hyco: The Story of Lea's Chapel United Methodist Church, Person County, North Carolina: 1750–2000 AD". Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- Corbitt 2000, p. 59.

- "History of Caswell County". NCCCHA.org. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- "Caswell, Richard". NCPedia.org. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- "African Americans and the Revolution". Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- "List of Free African Americans in the Revolution: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland, and Delaware". Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- "African Americans - Part 2: Life under slavery | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- "Historical Sketch". Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- "Bright Leaf Tobacco". NCpedia.org. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- "Slade, Abisha". Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- "Historical Perspectives of Caswell County". Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- "Yanceyville in "Life" Magazine: 1941". April 26, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- "Percival, William (fl. 1850s)". Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- Onion, Rebecca (March 16, 2015). "A Telephone Map of the United States Shows Where You Could Call Using Ma Bell in 1910". Slate. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- "National Register of Historic Places: Caswell County Training School" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- Messenger, The Caswell. "caswellmessenger.com | Serving Caswell County since 1926". The Caswell Messenger. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- Powell 1977.

- "United States Census Bureau". Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- "Caswell County Textile Industry" (PDF). Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- "History of Yanceyville". Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- "Business & Entrepreneurship". AllinCaswellNC.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- "North Carolina in the Civil War". NCPedia.org. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- "Secession". Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- "Civil War (1861–1865)". NCCCHA.org. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- "Map showing the distribution of the slave population of the southern states of the United States. Compiled from the census of 1860". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- "The Emancipation Proclamation". October 6, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- "Reconstruction, by Allen W. Trelease, 2006". Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- "The Kirk-Holden War of 1870 and the Failure of Reconstruction in North Carolina" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- "Black Codes". Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- "Black Codes in North Carolina, 1866". Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- "Reconstruction". Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- "All Amendments to the United States Constitution". University of Minnesota Human Rights Library.

- "North Carolina Counties – U.S. Census Bureau, 1870" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- "The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship". Library of Congress. February 9, 1998. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- "Constitutional Convention, 1868: "Black Caucus"". Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- "Reconstruction in North Carolina". Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- Brisson 2011, pp. 137–139.

- Brisson 2011, p. 139.

- Brisson 2011, pp. 139–140.

- Brisson 2011, p. 141.

- Brisson 2011, p. 143.

- Ashe 1925, p. 1114.

- Brisson 2011, p. 146.

- Brisson 2011, pp. 146–147.

- Brisson 2011, pp. 148–152.

- Brisson 2011, p. 152.

- "Conservative Party". Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- "Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka". August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- The "Brown II," "All Deliberate Speed" Decision ~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

- "The Pupil Assignment Act: North Carolina's Response to Brown v. Board of Education". Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- "Caswell County History, Web Log – Caswell County, North Carolina: School Integration". NCCCHA.org. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- "Desegregation Action is Filed," The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), December 11, 1956, p1

- "43 Negroes Seek Entry into Schools," The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, NC), August 6, 1957, p4-A

- "Jeffers v. Whitley, 197 F. Supp. 84 (M.D.N.C. 1961)". Justia Law. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- "Caswell Negroes' Appeal Step Taken," The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, NC), January 31, 1962, p12-A

- "Judge Rules on School Integration," The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, NC), December 22, 1962, p1

- "Two Area Men Wounded: Caswell Scene Now Calm," The Daily Times-News (Burlington, NC), January 23, 1963, p1

- "Two White Men Wounded in Caswell Integration," The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), January 23, 1963, p1

- Brown 2004, pp. 53–57, 78–79.

- "Suit Claims Pupil Abuse in Caswell," The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), March 19, 1963, p9

- "Caswell Hearing Recessed," The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), August 17, 1966, p3

- "Caswell Answers Questions on School Desegregation," The Danville Register (Danville, VA), December 21, 1966, p1

- "Caswell County Training School,1933–1969: Relationships between Community and School" (PDF). Harvard Educational Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Caswell Notified Compliance Lacking for U.S. Funds," The Danville Register (Danville, VA), December 6, 1966, p1

- "Judge Rules Caswell in Compliance," The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), April 11, 1969, p3

- Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South by Vanessa Siddle Walker (University of North Carolina Press, 1996) p192

- "Caswell Ordered To Integrate," The Daily Times-News (Burlington, NC), August 24, 1968, p1

- "Caswell County High School". Flickr. August 21, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- "Edwards, Donna - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- "Murphey, Archibald Debow". Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- "Saunders, Romulus Mitchell - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- "Yancey, Bartlett - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- "Saunders, Romulus Mitchell". Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- "Archibald Murphey – North Carolina Digital History". Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- "Keeping It REAL: Why Congress Must Act to Restore Pell Grant Funding for Prisoners". January 6, 2016. SSRN 2711979. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- "Caswell County Genealogy". CaswellCountyNC.org. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- "Tobacco: Historical Sketch". Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- "2020 County Gazetteer Files – North Carolina". United States Census Bureau. August 23, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- Powell 1976, p. 93.

- "Geography: Overview". Caswell County Historical Association. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- "NCWRC Game Lands". www.ncpaws.org. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- "Country Line Creek (in Caswell County, NC)". northcarolina.hometownlocator.com. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- "FARMER LAKE | Caswell County | NC". Caswell County NC. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- "Hogans Creek (in Caswell County, NC)". northcarolina.hometownlocator.com. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- "Moon Creek (in Caswell County, NC)". northcarolina.hometownlocator.com. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- "North Fork Rattlesnake Creek (in Caswell County, NC)". northcarolina.hometownlocator.com. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- Novak, Steven. "Fish Wildwood Lake – Caswell County, North Carolina". Lake-Link. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- "Locations". Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- "The Future of Reidsville, NC". rockitinreidsville. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- "(6W4) Yanceyville Municipal Airport". Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- "Danville, Virginia". Amtrak.com. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- "CATS: Quick Info". Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- "Caswell Correctional Center". Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- "Dan River Prison Work Farm". Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- "Decennial Census". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- "American Community Survey". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Department Directory". CaswellCountyNC.gov. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Staff Directory". CaswellCountyNC.gov. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Who We Are and What We Do". PTRC.org. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Caswell County". North Carolina Judicial Branch. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Caswell County". Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- "Caswell Government". Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- "Caswell County Representation". Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- "Doing Business". Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- "Whippoorwill Herb Co. – About Us". Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- "Home". Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- "AboutUs". Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- "Industrial Parks". CaswellCountyNC.gov. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- "CoSquare – Center of Entrepreneurship". Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- "Yanceyville, NC: Census Place". Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- "Places to visit about 1 hour from Yanceyville". Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- "Leadership & Vision". Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- "Caswell County Schools". Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- "About CHC". Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- "Sovah Family Medicine – Yanceyville". Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- "YAD Healthcare". Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- "Caswell House – Exceptional Senior Living". Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- "Area Info". Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: tinacarrollbsa (June 27, 2021), Boy Scout Camp, Cherokee Scout Reservation, Yanceyville, NC, retrieved June 27, 2021

- "Parks & Recreation". Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- "Senior Services". County of Caswell, North Carolina. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- "Providence Fire & Rescue 2012 Spring Fling Festival". 2012. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- "2021 Hoedown set for Saturday, September 25". CaswellMessenger.com. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- "Preserving the past, embracing the future; Looking back at 2008". NewsofOrange.com. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- Annual Events Archived August 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Caswell County Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- "Caswell celebrates heritage with festival". GoDanRiver.com. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- M. Ruth Little (July 2014). "William Henry and Sarah Holderness House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places – Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- "National Register Database and Research". Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- "Home". YanceyvilleNC.gov. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- "Milton Studio Art Gallery". Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- "Piedmont Triad Visitor Center". Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- "Yoder's Country Market". Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- "Caswell Civic Center". County of Caswell, North Carolina. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- "Caswell County Library". County of Caswell, North Carolina. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- "A. Oveta Fuller, Ph.D." Microbiology & Immunology. September 23, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- "Totten, Henry Roland". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- Floyd, Mike. "CM columnist Mel Melton leads a Zydeco band as well as cooks cajun". The Caswell Messenger. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- "John Gunn". Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- "Neal Watlington". Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- "Carl Willis". Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- Rsf (October 11, 2009). "Caswell County North Carolina: Giles Mebane (1809–1899)". Caswell County North Carolina. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- "Caswell County North Carolina Ancestral Trackers". www.ancestraltrackers.net. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- "Hugh B. Webster". Retrieved March 8, 2022.

Works cited

- Ashe, Samuel A'Court (1925). History of North Carolina. Vol. II. Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton. OCLC 244120893.

- Brisson, Jim D. (April 2011). "'Civil Government Was Crumbling Around Me': The Kirk-Holden War of 1870". The North Carolina Historical Review. 8 (2): 123–163. JSTOR 23523540.

- Brown, Deborah F. (2004). Dead-End Road. ISBN 9781418427832.

- Corbitt, David Leroy (2000). The formation of the North Carolina counties, 1663-1943 (reprint ed.). Raleigh: North Carolina Division of Archives and History. OCLC 46398241.

- Powell, William S. (1976). The North Carolina Gazetteer: A Dictionary of Tar Heel Places. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807812471.

- Powell, William S. (1977). When the Past Refused to Die: A History of Caswell County, North Carolina, 1777-1977. Durham, NC: Moore Pub. Co.

- Sartin, Ruby Pearl (1972). Caswell County: The First Century, 1777–1787. Greensboro: The University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG): College Collection.

- Walker, E.V. (1993). Caswell County Training School, 1933–1969: Relationships between Community and School. Harvard Educational Review, 63, 161–183.

- Walker, Vanessa Siddle (1996). Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

External links

Geographic data related to Caswell County, North Carolina at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Caswell County, North Carolina at OpenStreetMap- Official website

- Caswell County History Website

- Caswell County Photograph Collection