Cataño, Puerto Rico

Cataño (Spanish pronunciation: [kaˈtaɲo]) is a town and municipality located on the northeastern coast of Puerto Rico, bordering the San Juan Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, and adjacent to the north and east by San Juan; north of Bayamón and Guaynabo; east of Toa Baja and west of Guaynabo and is part of the San Juan Metropolitan Area. Cataño is spread over 7 barrios and Cataño Pueblo (the downtown area and the administrative center of the city). It is part of the San Juan-Caguas-Guaynabo Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Cataño

Municipio Autónomo de Cataño | |

|---|---|

Town and Municipality | |

Aerial view of Cataño | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: "El Pueblo Que Se Negó a Morir", "La Antesala de la Capital", "El Pueblo Olvidado" "La Ciudad de un Nuevo Amanecer" | |

| Anthem: "Cataño" | |

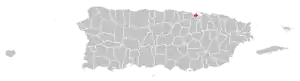

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Cataño Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°26′42″N 66°07′04″W | |

| Commonwealth | |

| Founded | July 1, 1927 |

| Barrios | 2 barrios |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Julio Alicea Vasallo (PNP) |

| • Senatorial dist. | 2 - Bayamón |

| • Representative dist. | 9 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.04 sq mi (18.23 km2) |

| • Land | 4.8 sq mi (12.5 km2) |

| • Water | 2.21 sq mi (5.73 km2) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 23,155 |

| • Rank | 54th in Puerto Rico |

| • Density | 3,300/sq mi (1,300/km2) |

| Demonym | Catañeses |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| ZIP Codes | 00962, 00963 |

| Area code | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

History

Hernando de Cataño was chosen to offer his medical services in Puerto Rico during Francisco Bahamonde de Lugo's tenure as Governor of Puerto Rico (1564–1568). He was one of the first physicians who arrived in Puerto Rico during its colonization[2] and, upon accepting his position, received as payment a piece of land across the San Juan islet. From that time, the region started to be recognized by the name of its original owner. As people started establishing in the area, Cataño was declared as a barrio of Bayamón. However, there wasn't much success in the town's development during these years due to its swamp-like terrain. Still, around 1690, a hermitage was established to allow residents to receive religious services without having to travel to Bayamón.

_in_San_Juan%252C_Puerto_Rico.tif.jpg.webp)

In the middle of the 19th century, a ferry company was founded to facilitate the transportation of merchandise and passengers through the San Juan Bay. This spurred a growth in the population of Cataño, transforming it into one of the most prosperous barrios of Bayamón. Still, attempts to separate themselves from Bayamón in 1839 were unsuccessful. On June 26, 1893, Bishop Antonio Puig y Montserrat separated the barrios of Cataño, Palo Seco, and Palmas from Bayamón's parish and established an independent parish for the residents of these sectors. In 1927, Cataño was officially declared a municipality with the name Hato de Palmas de Cataño, which overtime was simply shortened to Cataño.

Politics played a crucial part in the foundation of the town, since Bayamón was controlled by an administration with opposing ideologies to those of the island's Legislature. The separation of Cataño from Bayamón was a strategy to weaken that opposition.[3]

With only five square miles of territory (12.5 km2), Cataño is the smallest municipality in Puerto Rico. It is less than half the size of Hormigueros, the next-smallest in area.

The people of Cataño were left in despair when Hurricane María struck on September 20, 2017, destroying their infrastructure and homes. With winds of 150 miles per hour the hurricane destroyed and flooded an estimated 650 homes and the roads became rivers (flooded).[4] An estimated 80% of homes in the Juana Matos area of Cataño were destroyed.[5]

Geography

Cataño consists mostly of flat plains that belong to the Northern region of Puerto Rico. Its northern shore falls on the San Juan Bay of the Atlantic Ocean.[6][7]

Bodies of water

Located in Cataño are a number of rivers, streams, named and unnamed creeks, and channels including:[8][9][10]

- Caño La Malaria (Malaria Channel)

- Río de Bayamón

- Río Hondo

Barrios

.jpg.webp)

Cataño is divided into only two barrios: Cataño barrio-pueblo, and Palmas.[11][12]

Sectors

Barrios (which are, in contemporary times, roughly comparable to minor civil divisions)[13] in turn are further subdivided into smaller local populated place areas/units called sectores (sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[14][15][16]

Special Communities

Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico (Special Communities of Puerto Rico) are marginalized communities whose citizens are experiencing a certain amount of social exclusion. A map shows these communities occur in nearly every municipality of the commonwealth. Of the 742 places that were on the list in 2014, the following barrios, communities, sectors, or neighborhoods were in Cataño: Cucharillas, Juana Matos, Puente Blanco, and Puntilla.[17][18]

Culture

Festivals and events

Cataño celebrates its patron saint festival in July. The Fiestas Patronales de Nuestra Sra. del Carmen is a religious and cultural celebration that generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[19][6]

Tourism

One of the main tourist attractions in Cataño is the boardwalk or tablado that commands a view of the San Juan Bay, including views of Fort San Felipe del Morro on the opposing side. There are several monuments and sculptures along the boardwalk, including a monument to Taíno culture called "India Taína".

.jpg.webp)

The Bacardi Distillery also offers tours of its facilities to visitors who want to learn about the rum manufacturing industry in the island and the Caribbean.[20]

Christopher Columbus statue

The town gained notoriety in 1998, when Mayor Edwin Rivera Sierra traveled to Russia and acquired a huge statue of Christopher Columbus called "Birth of the New World". The statue Columbus by Tsereteli was designed by artist Zurab Tsereteli and would measure 350 feet (110 m) when erected. Tsereteli had offered the statue to the United States as a gift in 1992 with the intention to use it for the celebrations of the 500th year of its voyage. However, it was rejected. The transportation of the statue from Russia to Cataño cost $2.4 million. After arriving on the island, the 2,700 bronze pieces of the statue were scattered in a terrain awaiting for funds for the project, but Rivera Sierra was unable to garner enough public support or funding for it. The statue was installed in Arecibo.[21]

Sports

Cataño has a number of professional sports teams, and there are several important sports facilities located in the town, including the Perucho Cepeda Stadium, the Pedro Rodríguez Gaya Boxing Coliseum, and the Cosme Beitía Salamo Coliseum.

Economy

Due to its location, Cataño has always played an important role as a port to the island. Fishing has also been a main source of economy for centuries. Bacardi, one of the largest rum manufacturers of the world, has a distillery in Cataño.

Other industries established in the town are refineries, commerce companies, transport and logistics, among others.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 8,504 | — | |

| 1940 | 9,719 | 14.3% | |

| 1950 | 19,865 | 104.4% | |

| 1960 | 25,208 | 26.9% | |

| 1970 | 26,459 | 5.0% | |

| 1980 | 26,243 | −0.8% | |

| 1990 | 34,587 | 31.8% | |

| 2000 | 30,071 | −13.1% | |

| 2010 | 28,140 | −6.4% | |

| 2020 | 23,155 | −17.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] 1930[23] 1930-1950[24] 1960-2000[25] 2010[26] 2020[27] | |||

Despite its small size, Cataño has a large population when compared to municipalities of similar areas. This is perhaps due to its location near the capital of San Juan. The population, according to the 2000 census, was 30,071 with a population density of 6,014.2 people per square mile (2,322.1 people/km2). Although the current population is almost the double of what it was in the 1950 census, the current census reflects a small decrease of inhabitants.

As a whole, Puerto Rico is populated mainly by people from a Mulatto (Of African and European descent) and European descent, with small groups of African and Asian people. Statistics taken from the 2000 census shows that 66.9% of Catañenses have Spanish or White ancestry, 8.6% are black, 0.8% are Amerindian etc.

| Race - Cataño, Puerto Rico - 2000 Census[28] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race | Population | % of Total |

| White | 20,427 | 67.9% |

| Black/African American | 2,279 | 7.6% |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 226 | 0.8% |

| Asian | 58 | 0.2% |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 7 | 0.0% |

| Some other race | 1,839 | 6.1% |

| Two or more races | 5,235 | 17.4% |

Government

After its initial establishment, Cataño belonged to the Bayamón region. From 1839 to 1845, there were some attempts to separate the barrio from Bayamón, but these were unsuccessful. However, on late 19th century, Bishop Antonio Puig y Montserrat managed to separate Cataño establishing their own parish. Cataño was finally declared a municipality on April 25, 1927, being its first mayor Alberto Dávila.

In 1987, Edwin Rivera Sierra was elected as Mayor of Cataño. He remained in the position for 16 years, quitting in 2003. He was replaced by Wilson Soto, who was then officially elected at the 2004 elections in Puerto Rico. After losing a reelection bid in 2008 against José Rosario, Soto was indicted on nine charges.[29]

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district II, which is represented by two senators. Migdalia Padilla and Carmelo Ríos Santiago have served as district senators since 2005.[30]

Symbols

The municipio has an official flag and coat of arms.[31]

Flag

The flag consists of nine horizontal stripes: four blue stripes and five white stripes (substituting for the silver color on the coat of arms). A white and green band traverses diagonally the drape in all its extension, from the upper hoist to the lower fly.[32]

The green color represents the palm trees that are also present in the coat of arms. The flag was officially adopted during José Alvarez Brunet tenure as mayor on September 5, 1974.[32]

Coat of arms

The coat of arms of Cataño consists of nine horizontal stripes of same the width: four blue and five silver. The colors of the coat and the flag represent the coat of arms of the family of Don Hernando de Cataño, an Hidalgo to whom the town owes its name. The color silver represents nobility and the color blue was used by hidalgos on their armories. It symbolizes royalty and serenity.[32]

On top of the coat of arms, there's a crown with three towers distinct of others coat of arms. The coat itself is surrounded by two green palm trees, an allusion to one of the original names of the town: Hato de las Palmas de Cataño.[32]

Name

Aside of its name, derived from its original owner, Cataño has several nicknames. The city is known as "La Antesala de la Capital" (the Foyer of the Capital) because of its location across the bay from the capital-city of San Juan. In the 1960s, the residents of Cataño jokingly called it "Fanguito Town" because of its many muddy streets and shacks built on stilts over tidal flats.[33][34][35][36]

Education

Cataño has several public and private schools managed by the Puerto Rico Department of Education.

Transportation

Puerto Rico Highway 22 provides access to Cataño from San Juan or from other adjacent towns. Like most other towns in the island, it has a public transportation system consisting of public cars. Taxis are also available around the town.

Cataño also has a ferry service known as La Lancha de Cataño, or the Ferry of Cataño. The ferry service, which has been working since 1853, operates a five-minute harbor route between Cataño and Old San Juan, and vice versa daily. There is a large ferry terminal at Cataño, and tourists can enjoy the view of the Castillo del Morro and the large cruise ships docked at the old San Juan terminal during this journey.[37]

There are 16 bridges in Cataño.[8]

Gallery

View of the San Juan Bay from the Cataño shore

View of the San Juan Bay from the Cataño shore Statue of Taíno Girl

Statue of Taíno Girl

References

- Bureau, US Census. "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "Municipio de Cataño Puerto Rico el Pueblo que se nego a morir, Lancheros de Cataño, Antesalistas de San Juan". Archived from the original on April 1, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- "Municipios: Cataño". Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- "María, un nombre que no vamos a olvidar. Cataño, la vida antes y después del huracán María" [Maria, a name we will never forget. Cataño, life before and after Hurricane María.]. El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). June 13, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- Leposa, Adam (September 22, 2017). "After Hurricane Maria, First Commercial Flight Returns to San Juan". Travel Agent Central. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- "Cataño Municipality". enciclopediapr.org. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH). Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Mapa de Municipios y Barrios: Cataño (1947)". Issuu (in Latin). Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- "Cataño Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. US Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 21, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- "Rios de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 23, 2008.

- "Jacksonville District Navigable Waters Lists" (PDF). saj usace army mil. SAJ. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- "Enciclopedia del Municipio de Cataño: Municipios" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Map of Cataño at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2018.

- "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Agencia: Oficina del Coordinador General para el Financiamiento Socioeconómico y la Autogestión (Proposed 2016 Budget)". Puerto Rico Budgets (in Spanish). Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (first ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- "Leyes del 2001". Lex Juris Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (1st ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, p. 274, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- "Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). August 8, 2011. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "Puerto Rico Festivales, Eventos y Actividades en Puerto Rico". Puerto Rico Hoteles y Paradores (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "Casa Bacardí". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- "Puerto Rico's Christopher Columbus Statue Survives Hurricane Maria". NPR. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 3-Population of Municipalities: 1930 1920 and 1910" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 4-Area and Population of Municipalities Urban and Rural: 1930 to 1950" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Bureau, US Census. "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "Ethnicity 2000 census" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- "El Vocero - Cargos criminales contra Wilson Soto". Archived from the original on March 30, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- Elecciones Generales 2008: Escrutinio General Archived November 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine on CEEPUR

- "Ley Núm. 70 de 2006 -Ley para disponer la oficialidad de la bandera y el escudo de los setenta y ocho (78) municipios". LexJuris de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- "CATAÑO". LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- Schorr, Alvin Louis (1963). Slums and social insecurity, an appraisal of the effectiveness of housing policies in helping to eliminate poverty in the United States. Washington DC: Washington, U. S. Govt. Print. Office. p. 8.

- Rivero, Yeidy M. (2004). "Caribbean Negritos Ramón Rivero, Blackface, and "Black" Voice in Puerto Rico". Television & New Media. 5 (4): 315–3. doi:10.1177/1527476404268424. S2CID 144630039.

- Torres, Daniel (2009). "Review: Review Essay: Estudios queer puertorriqueños". Chasqui. 38 (2): 141–147.

- Foster, William Z. (1948). The crime of El Fanguito : an open letter to President Truman on Puerto Rico. New York: New Century Publishers. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- Caro, Leysa (May 8, 2016). "Larga historia en la lancha de Cataño". El Nuevo Día. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

External links

Further reading

- Mapa de municipios y barrios - Cataño - Memoria Núm. 2 (PDF). University of Puerto Rico: Junta de Planificacion, Urbanizacion, y Zonificacion de Puerto Rico. 1946.