Cedarburg, Wisconsin

Cedarburg (/ˈsiːdərbɛrɡ/ SEE-dər-burg)[5] is a city in Ozaukee County, Wisconsin, United States. Located about 20 miles (32 km) north of Milwaukee and in close proximity to Interstate 43, it is a suburban community in the Milwaukee metropolitan area. The city incorporated in 1885, and at the time of the 2020 census the population was 12,121.

City of Cedarburg, Wisconsin | |

|---|---|

Cedarburg City Hall, located in the Washington Avenue Historic District | |

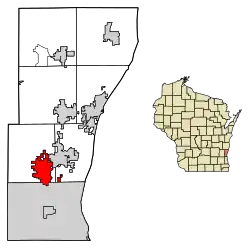

Location of Cedarburg in Ozaukee County, Wisconsin. | |

| Coordinates: 43°17′18″N 87°59′15″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Ozaukee |

| Settled | 1840s |

| Incorporated | 1885 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor/Council |

| • Mayor | Mike O’Keefe |

| • Administrator | Mikko Hilvo |

| • Clerk | Tracie Sette |

| • Common council | Aldermen

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.88 sq mi (12.65 km2) |

| • Land | 4.84 sq mi (12.52 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.12 km2) |

| Elevation | 784 ft (239 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 12,121 |

| • Density | 2,399.30/sq mi (926.40/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Zip Code | 53012 |

| Area code | 262 |

| FIPS code | 55-13375[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1562869 [2] |

| Website | ci.cedarburg.wi.us |

Like many of Ozaukee County's cities and villages, the City of Cedarburg began as a mill town. German immigrants began building hydropowered gristmills and woolen mills along Cedar Creek in the 1840s. The community that sprang up around the mills is now downtown Cedarburg. The city was distinctly German into the early 20th century, with several Lutheran churches, a brewery, a European-style spa resort called Hilgen Spring Park,[6] and many German cultural associations, including two Turner societies.[7]

Cedarburg changed significantly during the period of post-World War II suburbanization. While the mills had all closed by the 1960s, the city experienced rapid population growth and the development of new commercial properties and housing subdivisions.[7] In spite of the changes, more than 200 of Cedarburg's historic buildings have been preserved,[8] and the city is home to eight listings on the National Register of Historic Places. The community profits from a vibrant tourist industry and hosts festivals and events throughout the year that attract visitors from other areas.[9]

Toponymy

When the first settlers—many of whom were German speakers—arrived in the area, they found white cedar trees growing on the banks of Cedar Creek. Early German-American settler Frederick Leuning built a cabin near the creek's eastern bank in 1843 and referred to his home as the "Cedarburg," meaning the "cedar castle" or the "fortress of the cedars." In December 1844, the early residents agreed to name the community Cedarburg.[10]

History

The earliest evidence of humans in the Cedarburg area is the Hilgen Spring Mound Site, located in the eastern part of the city of Cedarburg, near Cedar Creek. The site consists of three conical burial mounds constructed by early Woodland period Mound Builders.[11] In 1968, archaeologists from the Milwaukee Public Museum found human burials and artifacts, including stone altars, arrowheads, and pottery shards, during an excavation of one of the mounds. Radiocarbon samples from the excavation date the mounds' construction to approximately 480 BCE, making it one of the oldest mound groups in the state.[12][13]

In the early 19th century, the land was inhabited by Native Americans, including the Potawatomi and Sauk tribes. The Potawatomi surrendered the land the United States Federal Government in 1833 through the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, which (after being ratified in 1835) required them to leave Wisconsin by 1838.[14][15] While many Native people moved west of the Mississippi River to Kansas, some chose to remain, and were referred to as "strolling Potawatomi" in contemporary documents because many of them were migrants who subsisted by squatting on their ancestral lands which were now owned by white settlers. Eventually the Native people who evaded forced removal gathered in northern Wisconsin, where they formed the Forest County Potawatomi Community.[16]

The first white settlement in the Cedarburg area was a community called "New Dublin," which later became Hamilton in the town of Cedarburg. The first resident was Joseph Gardenier, who built a log shanty on Cedar Creek as his headquarters for surveying for the construction of the Green Bay Road.[17] In 1848, Hamilton became the first stop on the stagecoach route between Milwaukee and Green Bay.[7]

Most of Cedarburg's early settlers were German immigrants. Ludwig Wilhelm Groth is usually credited with being the first settler of Cedarburg. He purchased land from the government on October 22, 1842, and began platting the banks of Cedar Creek. In 1845, Frederick Hilgen and William Schroeder built a wooden gristmill on Cedar Creek. After eleven years of operation, they replaced the original structure with the five-story, stone Cedarburg Mill, which became the focal point of the new community. Five dams and mills were eventually built along the creek in what are now the city and town of Cedarburg, including the 1864 Hilgen and Wittenberg Woolen Mill, which was the largest woolen mill west of Philadelphia.[7]

In 1870, the Milwaukee and Northern Railway connected Cedarburg to Milwaukee. By 1873 the rail line extended from Milwaukee to Green Bay, connecting Cedarburg and other small communities to larger markets. Cedarburg continued to grow and prosper due to its rail connections, while the surrounding communities of Hamilton, Decker Corner and Horns Corners remained more characteristically rural. Cedarburg incorporated in 1885. At the time, the population was approximately 1,000 people.[7]

In 1897, the woolen mill purchased an electrical generator, which produced the first electric light in the town. In 1901, the city contracted an electric plant with steam engines running two 75 kW generators, and in 1909 the Cedarburg Electric Light Commission was formed to run the utility. In 1923, responsibility for water and sewerage was given to the utility, and it was renamed the Light & Water Commission. The utility is still in business today, and is one of 82 municipally owned electric utilities in Wisconsin.[18]

_(14760072742).jpg.webp)

In 1907, Cedarburg became a stop on the Milwaukee-Northern interurban passenger line. The company operated an office and shop in Cedarburg into the 1920s, when it was purchased by The Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Company. The company continued passenger rail service to Cedarburg until 1948, when the Ozaukee County line declined due to increased use of personal automobiles and better roads.[19]

Cedarburg grew rapidly during the post-war suburbanization and economic prosperity. The population increased by more than 84% between 1950 and 1960, from 2,810 to 5,191. This period of population growth witnessed the growth of new industries and housing developments.[7]

Geography

Cedarburg is located at 43°17'56" North, 87°59'13" West (43.29896, −87.987209).[20] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.87 square miles (12.61 km2), of which, 4.83 square miles (12.51 km2) of it is land and 0.04 square miles (0.10 km2) is water.[21] The City of Cedarburg is bordered by the Village of Grafton to the east, the City of Mequon to the south, and the Town of Cedarburg to the north and west.

The city is located in the Southeastern Wisconsin glacial till plains that were created by the Wisconsin glaciation during the most recent ice age. The soil in area is a mixture of well-draining material, loess, and loam, which all overlie a layer of glacial till. Most of the City of Cedarburg is located on top of a Silurian limestone deposit. There were several quarries active in the area, including the now-defunct Groth Quarry in Zeunert Park where excavators discovered fossils from a prehistoric reef. The early settlers utilized the area's limestone as a building material, and some mid-19th-century limestone structures still stand today.[22]

Cedar Creek runs through the city parallel to the Washington Avenue historic and commercial district. In 1993, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources believed that Cedar Creek had the PCB contamination in the state.[23] The creek is now part of an Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site in the city.[24] Despite cleanup efforts, the Wisconsin DNR advises against eating any fish caught in the creek downstream from the Bridge Road dam.[25]

Before white settlers arrived in the area, the Cedarburg area was an upland forest dominated by American beech and sugar maple trees. There were also white cedars growing along Cedar Creek. Much of the original forest was cleared to prepare the land for agriculture.[22] In the 21st century, the City of Cedarburg plants and maintains over 8,000 trees in public spaces, and the Arbor Day Foundation has recognized Cedarburg through its Tree City USA program.[26]

As land development continues to reduce wild areas, wildlife is forced into closer proximity with human communities like Cedarburg. Large mammals, including white-tailed deer, coyotes, and red foxes can be seen within the city limits. There have been infrequent sightings of black bears in Ozaukee County communities, including a 2005 report of a bear in a Cedarburg city park.[27] Many birds, including great blue herons and wild turkeys are found in and around the City of Cedarburg.[28] The Wisconsin Bird Conservation Initiative considers the Cedarburg Bog, located north of the city in the Town of Saukville, to be a Wisconsin Important Bird Area.[7] The rare Goldenseal plant grows in a woodland on the northern boundary between the city and the Town of Cedarburg.[22]

The region struggles with many invasive species, including the emerald ash borer, common carp, reed canary grass, the common reed, purple loosestrife, garlic mustard, Eurasian buckthorns, and honeysuckles.[29]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 945 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,361 | 44.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,626 | 19.5% | |

| 1910 | 1,777 | 9.3% | |

| 1920 | 1,738 | −2.2% | |

| 1930 | 2,055 | 18.2% | |

| 1940 | 2,245 | 9.2% | |

| 1950 | 2,810 | 25.2% | |

| 1960 | 5,191 | 84.7% | |

| 1970 | 7,697 | 48.3% | |

| 1980 | 9,005 | 17.0% | |

| 1990 | 9,895 | 9.9% | |

| 2000 | 10,908 | 10.2% | |

| 2010 | 11,412 | 4.6% | |

| 2020 | 12,121 | 6.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] | |||

As of 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $56,431, and the median income for a family was $66,932. Males had a median income of $51,647 versus $30,979 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,455. About 1.8% of families and 2.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.0% of those under age 18 and 3.6% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 11,412 people, 4,691 households, and 3,060 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,362.7 inhabitants per square mile (912.2/km2). There were 4,916 housing units at an average density of 1,017.8 per square mile (393.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 96.3% White, 0.8% African American, 0.1% Native American, 1.5% Asian, 0.3% from other races, and 1.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.7% of the population.

There were 4,691 households, of which 31.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.1% were married couples living together, 8.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 2.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.8% were non-families. 30.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 3.00.

The median age in the city was 43.1 years. 24.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 6.5% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 22% were from 25 to 44; 30% were from 45 to 64; and 16.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.4% male and 52.6% female.

Economy

Early industry

As is the case in many of the cities and villages in Ozaukee County, Cedarburg's earliest businesses were hydropowered mills. In 1843, Frederick Luening built the Columbia Mill, a gristmill, which was the first mill on Cedar Creek.[31] Following the Columbia Mill in 1845, Frederick Hilgen and William Schroeder built another gristmill further upstream. Neither of these structures remain, but other 19th century mills do survive, including the 1853 Concordia Mill; the 1855 Cedarburg Mill, which replaced Hilgen and Schroeder's earlier grist mill; the 1864 Hilgen and Wittenberg Woolen Mill; and the 1871 Excelsior Mill, which was later retooled as the Cedarburg Wire and Nail Factory.[32] Other early structures near the creek that survive include an 1848 brewery.[33]

20th century industry

In the 20th century, Cedarburg had some manufacturing firms. Carl Kiekhaefer founded Mercury Marine in Cedarburg in 1939, and the company operated a plant on St. John Avenue until 1982. The building was demolished in 2005. Amcast operated an aluminum die-casting plant on Hamilton Road until 2005.[34] Both companies polluted the soil and waters of Cedar Creek with PCBs, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is using Superfund money to clean up the sites.[35]

Tourism

The Hilgen and Wittenberg Woolen Mill closed in 1968 and sat vacant for several years, until an offer was made to buy the buildings. The prospective owner intended to tear them down and build a gas station and a mini-mart. Then mayor, Stephan Fischer, told him he would need a demolition permit. There was no such thing, but it bought enough time that the buildings could be saved.[36] William Welty bought the buildings on the corner and street, opening a restaurant. Jim Pape then bought the mill buildings on the creekside, opening a winery. Known as the Cedar Creek Settlement, the rest of the space was rented out to shops, studios and restaurants.[37]

This began a tourism boom in Cedarburg. More galleries and studios opened, as well as souvenir shops and other attractions. Business associations started weekend festivals, which attracted even more people to the city. As of 2020, the city hosts Winter Festival in February, Strawberry Festival in June, Wine and Harvest Festival in September, and German-themed Oktoberfest in October, as well as Christmas events in November and December.[9] In the summer months, local companies sponsor a concert series called Summer Sounds which takes place at Cedar Creek Park.[38]

Many Cedarburg residents who do not work in the tourist industry commute for work, reflecting the larger trend of Ozaukee County as a majority-commuter community.[39]

| Largest Employers in Cedarburg, 2013[40] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Employer | Industry | Employees |

| 1 | Cedarburg School District | Primary and secondary education | 100–249 |

| 2 | City of Cedarburg | Public administration | 100–249 |

| 3 | BMO Harris Bank | Commercial banking | 100–249 |

| 4 | Olsen's Piggly Wiggly | Retail (Grocery) | 100–249 |

| 5 | Cedar Springs Health & Rehabilitation | Nursing Care | 100–249 |

| 6 | Carlson Tool and Mfg Corp. | Industrial mold manufacturing | 100–249 |

| 7 | Kemps Dairy | Milk processing | 50–99 |

| 8 | Advanced Technology International | Fabricated metal manufacturing | 50–99 |

Culture

Cedarburg's first German settlers' influence is still visible in the 21st Century. There are six Lutheran congregations in the community; Trinity Lutheran Church on Columbia Road is the oldest, having been founded in 1843 by a group of Old Lutheran immigrants from the Prussian Province of Pomerania.[41] Many 19th century buildings have German inscriptions on their capstones, and the oldest gravestones in city cemeteries are in German. The Zur Ruhe Cemetery on Bridge Street takes its name from a German phrase meaning "to rest."

Cedarburg Public Library

The Cedarburg Women's Club established the city's public library in 1911. In addition to its collection of approximately 72,000 items, the library provides patrons with digital resources, study rooms and a community meeting room in its 25,500 square foot facility. Cedarburg Public Library is a member of the Monarch Library System, comprising thirty-one libraries in Ozaukee, Sheboygan, Washington, and Dodge counties.[42]

Events and festivals

Cedarburg hosts the Ozaukee County Fair at Firemen's Park, on Washington Avenue, north of downtown. The fair has been held annually since 1859. The event is free, and includes live music, truck and tractor pulls, rides, a demolition derby, and 4-H and livestock exhibitions.[43]

Firemen's Park also hosts four "Maxwell Street Days" flea markets each summer as a fundraiser for the Cedarburg Fire Department. Up 600 vendors can have tables at one of the flea markets.[44]

As of 2020, the city hosts five weekend festivals, including Winter Festival in February, Strawberry Festival in June, Wine and Harvest Festival in September, and German-themed Oktoberfest in October, as well as Christmas events in November and December.[9] In the summer months, local companies sponsor a concert series called Summer Sounds which takes place at Cedar Creek Park.[38]

Museums

- Cedarburg Art Museum: Housed in the 1898 mansion of a wealthy mill owner's daughter, the Cedarburg Art Museum features a permanent collection of forty-nine artworks, as well as curated temporary exhibitions.[45]

- Cedarburg History Museum: The Cedarburg History Museum maintains a museum devoted to Cedarburg's history in the historic Hilgen & Schroeder Mill Store. The building also houses the Cedarburg Visitor Center and the Roger Christiansen General Store exhibit, which is a walk-in diorama of an early 20th century general store.[46][47] In early 2021, the collection of the former Chudnow Museum of Yesteryear moved to the care and custody of the Cedarburg museum to enhance the latter's collection of local artifacts.[48]

- Kuhefuss House Museum: Located in the Washington Avenue Historic District, the 1849 Kuhefuss House Museum offers tours and special exhibitions to educate the public about early life in Cedarburg.[49]

- Wisconsin Museum of Quilts & Fiber Arts: Located in on a farmstead from the 1850s, the Wisconsin Museum of Quilts & Fiber Arts opened in 2001 and maintains a collection of over 8,000 pieces of art. The museum is "dedicated to creating, preserving and teaching fiber arts."[50]

Performing arts

- Cedarburg Cultural Center: Located on Washington Avenue, the Cedarburg Cultural Center hosts live performance and art exhibitions, offers art classes, and maintains the Kuhefuss House Museum.[51]

- Cedarburg Performing Arts Center: The performing arts center is a 580-seat theater connected to Cedarburg High School, which offers a visiting artist series.

- Rivoli Theatre: Opened in 1936, the Rivoli is a one-screen Art Deco cinema on Washington Avenue.

Religion

There are at least six Lutheran churches in Cedarburg. Four churches—Advent, Faith, Immanuel, and Trinity—are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.[41][52][53][54] First Immanuel Lutheran is part of the Missouri Synod,[55] and Redeemer Evangelical Lutheran Church is part of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod.[56]

The city also has the Methodist Community United Methodist Church;[57] the Christian Scientist First Church of Christ, Scientist of Cedarburg;[58] the Heritage Baptist Church, a Regular Baptist congregation affiliated with the Wisconsin Association of Regular Baptist Churches;[59] the Roman Catholic St. Francis Borgia parish;[60] and the St. Nicholas Orthodox Church of the Antiochian Orthodox tradition.[61] The evangelical Alliance Bible Church is located adjacent to the Cedarburg city limit in the City of Mequon.[62]

Law and government

Cedarburg is organized under a mayor–council government. The current mayor is Mike O'Keefe, who was elected to his first four-year term on April 3, 2018.[63] Seven aldermen sit on the Cedarburg common council in addition to the mayor. The council meets on the second and last Monday of each month at 7 p.m.[64] The city's day-to-day operations are managed by a full-time city administrator.[65]

As part of Wisconsin's 6th congressional district, Cedarburg is represented by Glenn Grothman (R) in the United States House of Representatives, and by Ron Johnson (R) and Tammy Baldwin (D) in the United States Senate. Duey Stroebel (R) represents Cedarburg in the Wisconsin State Senate, and Robert Brooks (R) represents Cedarburg in the Wisconsin State Assembly.[66]

Cedarburg Fire Department

Cedarburg's volunteer fire department was founded in 1866.[67]

Since 1966, the fire department has organized "Maxwell Street Days" flea markets each summer as a fundraiser.[44]

Cedarburg Police Department

The Cedarburg Police Department was established in 1885 when the city incorporated.[68]

Utilities

The Cedarburg Light & Water Utility is one of approximately 2,200 publicly owned utilities in the United States. It was formed in 1909 to operate the city's first power plant, which had been built eight years earlier.[18] The utility is responsible for both electricity and water supply in the city, and is run by a commission of seven residents appointed by the mayor, one of whom must be a member of city council.[69]

Education

Cedarburg's public schools are operated by the Cedarburg School District. The district has three elementary schools, serving grades kindergarten through fifth grade: Parkview Elementary, Thorson Elementary, and Westlawn Elementary. Each elementary school serves a different neighborhoods of the city. Webster Middle School serves the entire district for grades six through eight, and Cedarburg High School serves grades nine through twelve.

The district serves the City of Cedarburg, the Town of Cedarburg, and some neighboring parts of the City of Mequon and the Village of Grafton. The district is governed by a seven-member elected school board, which meets on the third Thursday of each month at Cedarburg High School. The district also a superintendent. Todd Bugnacki, the current superintendent, has held the position since 2015.[70]

The district frequently appears on lists of the best schools in the state.[71]

The city also has two parochial schools that serve students from kindergarten through eight grade: First Immanuel Lutheran School and St. Francis Borgia Catholic School.

Transportation

Cedarburg is located approximately three miles west of Interstate 43 exit 89. The city is also located south of the intersection of Wisconsin Highway 60 and Washington Avenue.

Cedarburg has limited public transit compared with larger cities. Ozaukee County and the Milwaukee County Transit System run the Route 143 commuter bus, also known as the "Ozaukee County Express," to Milwaukee via Interstate 43. The bus stops at the park-and-ride lot by Cedarburg's interstate on- and offramps. The bus operates eight trips to Milwaukee on weekday mornings and nine trips from Milwaukee on weekday evenings, corresponding to peak commute times.[72][73] Ozaukee County Transit Services' Shared Ride Taxi is the public transit option for traveling to sites not directly accessible from the interstate. The taxis operate seven days a week and make connections to Washington County Transit and Milwaukee County Routes 12, 49 and 42u.[72][74]

The City of Cedarburg has sidewalks in most areas, as well as the Ozaukee Interurban Trail, which is for pedestrian and bicycle use, and connects the city to the neighboring communities of Grafton and Mequon, and continues north to Sheboygan County and south to Milwaukee County.

Cedarburg grew from a rural hamlet into an incorporated city in part because of its 19th century rail connections. From 1907 to 1948, Cedarburg was connected to Milwaukee and Sheboygan by an interurban passenger rail line, which fell into disuse following World War II and was converted into a bicycle and pedestrian trail in the 1990s. The Wisconsin Central Ltd. railroad provides freight rail service to Cedarburg as part of its Saukville subdivision.[75] While Cedarburg has not had passenger rail in many decades, passenger rail is offered by Amtrak in nearby Milwaukee at the Milwaukee Intermodal Station.

Parks and recreation

The City of Cedarburg maintains thirty-four parks, encompassing a total of 146 acres. These range from as small as the .1 acre Doctor's Park on the corner of Washington Avenue and Mill Street and the .25 acre Skateboard Park on Johnson Avenue to the twenty-three acre Centennial Park, which includes a public pool, two ponds, a sledding hill, and a playground designed to accommodate children with disabilities.

The Ozaukee Interurban Trail runs through the City of Cedarburg, following the former route of the Milwaukee Interurban Rail Line. The southern end of the trail is at Bradley Road in Brown Deer which connects to the Oak Leaf Trail (43°09′48″N 87°57′39″W), and its northern end is at DeMaster Road in the Village of Oostburg Sheboygan County (43°36′57″N 87°48′08″W). The Cedarburg segment of the trail was completed in 1996, and connects the community to neighboring Grafton and Mequon.[76]

Cedarburg is also home to several private recreational facilities, including a golf course, two bowling alleys, the Milwaukee Curling Club, and the Ozaukee Ice Center, a year-round hockey and skating rink.[77]

Notable people

- Jesse Anderson, convicted murderer[78]

- Paul Clement, 43rd Solicitor General of the United States[79]

- Jacob Dietrich, Wisconsin legislator[80]

- Gregory Euclide, visual artist

- Janine P. Geske, Justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court[81]

- Amadeus William Grabau, geologist and paleontologist[82]

- Frederick W. Horn, Wisconsin legislator[83]

- Edward H. Janssen, Treasurer of Wisconsin[84]

- Eric Larsen, polar explorer[85]

- Clarence Kenney, football player[86]

- Peter F. Leuch, Wisconsin legislator

- Edna Scheer, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player[87]

- John Schuette, Wisconsin State Senator

- Jonathan Stiever, baseball player[88]

- Ralph E. Suggs, U.S. Navy admiral

- Josh Thompson, country singer[89]

- Jason Upton, Christian singer/songwriter

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Cities -". Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- "Cedarburg Woolen Mill; Hilgen Springs". Milwaukee Daily News. July 16, 1878. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- "Encyclopedia of Milwaukee: Cedarburg". University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- "History of Cedarburg". City of Cedarburg. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- "Festivals of Cedarburg". Festivals of Cedarburg, Inc. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Harold E. Hansen. Sketches of Cedarburg: Celebrating 100 Years. Cedarburg: Cedarburg Commemorative Corp., 1985, p. 1.

- "Ecological Landscapes of Wisconsin: Central Lake Michigan Coastal Ecological Landscape" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- "Searching for the 'Spirit of the Place'". Shepherd Express. May 17, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- "Hilgen Spring Mound Site Revisited: Lecture". Localeben. May 26, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- "Early history of Ozaukee County, Wisconsin". University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Gerwing, Anselm J. (Summer 1964). "The Chicago Indian Treaty of 1833". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 57 (2): 117–142. ISSN 0019-2287. JSTOR 40190019.

- "Potawatomi History". Milwaukee Public Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- "Town of Cedarburg". History of Washington and Ozaukee Counties, Wisconsin. Chicago: Western Publishing. 1881. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- Cedarburg Light & Water Archived December 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "History of The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company". The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Transit Historical Society. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- "Inventory of Agricultural, Natural, and Cultural Resources". Ozaukee County. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Cedar Creek has highest PCB count". Racine Journal Times. November 21, 1993. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Environmental Protection Agency. EPA adds Cedarburg, Wis., site to Superfund list

- "Choose Wisely, 2015: A health guide for eating fish in Wisconsin" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Cedarburg: Forestry". City of Cedarburg. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Beyond the Trees: Stories of Wisconsin Forests. Candice Gaukel Andrews. May 30, 2011. ISBN 9780870204678. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Ecological Landscapes of Wisconsin" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- "Central Lake Michigan Coastal Ecological Landscape" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Early history of Ozaukee County, Wisconsin: Columbia Mill". University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Early history of Ozaukee County, Wisconsin: Columbia Mill". University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Cedarburg Brewery Complex". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- "Cedarburg wants $3 million TIF to redevelop former Amcast factory". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Superfund Site: Cedar Creek, Cedarburg, WI". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Steffes, Judy (November 9, 2007). "Cedarburg has formula for model downtown". BizTimes.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2009.

- "History Cedarburg Woolen Mill Cedar Creek Settlement". Ozaukee County. Archived from the original on August 3, 2007. Retrieved May 19, 2009.

- "Summer Sounds". Cedarburg Music Festivals. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- "Encyclopedia of Milwaukee: Ozaukee County". University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "City of Community Economic Profile" (PDF). July 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- "Trinity Lutheran Church". Trinity Lutheran Church. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Cedarburg Public Library". Cedarburg Public Library. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Ozaukee County Fair". Ozaukee County Fair. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Cedarburg Fire Department: Maxwell Street Days". Cedarburg Fire Department. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Cedarburg Art Museum". Cedarburg Cultural Center. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Cedarburg General Store Museum". Visit Ozaukee. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Cedarburg History Museum". Cedarburg Cultural Center. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Jozwik, Catherine (January 15, 2021). "Chudnow Museum Collection to Move to Cedarburg". Shepherd Express. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- "Kuhefuss House Museum". Visit Ozaukee. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Wisconsin Museum of Quilts & Fiber Arts". Wisconsin Museum of Quilts & Fiber Arts. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Cedarburg Cultural Center". Cedarburg Cultural Center. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Advent Lutheran Church". Advent Lutheran Church. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Faith Lutheran Church". Faith Lutheran Church. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Immanuel Lutheran Church". Immanuel Lutheran Church. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "First Immanuel Lutheran Ministries: Our History". First Immanuel Lutheran Ministries. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Redeemer Evangelical Lutheran Church". Redeemer Evangelical Lutheran Church. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Community United Methodist Church". Community United Methodist Church. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "First Church of Christ, Scientist, Cedarburg". First Church of Christ, Scientist, Cedarburg. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Heritage Baptist Church: About". Heritage Baptist Church. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "St. Francis Borgia Catholic Church". St. Francis Borgia Catholic Church. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "St. Nicholas Orthodox Church: About Us". St. Nicholas Orthodox Church. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Alliance Bible Church: What We Believe". Alliance Bible Church. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Now News Group (April 3, 2018). "Cedarburg voters promote Alderman Mike O'Keefe to mayor". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "City of Cedarburg: Common Council". City of Cedarburg. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "City of Cedarburg: City Administrator". City of Cedarburg. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- "Wisconsin State Legislature Map". Wisconsin State Legislature. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Cedarburg Fire Department: History". Cedarburg Fire Department. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Cedarburg Police Department: History". City of Cedarburg. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Utility Commission". Cedarburg Light & Water Utility. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "Cedarburg School District: Office Of The Superintendent". Cedarburg School District. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- "Cedarburg School District: District Accomplishments". Cedarburg School District. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- "MCTS Route 143: Ozaukee County Express". Wisconsin DOT. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "Ozaukee County, Cedarburg (I-43/County C)". Milwaukee County Transit System. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "OCTS: Shared Ride Taxi". Ozaukee County Transit Services. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "Wisconsin Railroads and Harbors 2020" (PDF). Wisconsin DOT. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "Park Facilities". City of Cedarburg, WI. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "Ozaukee Ice Center". Ozaukee Ice Center. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Worthington, Rogers (April 28, 1992). "Once A Victim, Now A Suspect". Chicago Tribune.

- "Paul D. Clement". Kirkland & Ellis. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- The Wisconsin Blue Book. Madison, WI: Democrat Printing Co. 1913. pp. 282.

- "Janine P. Geske (1949- )". Wisconsin Court System. March 7, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- "Amadeus William Grabau - American Geologist". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- 'Wisconsin Blue Book 1893,' Biographical Sketch of Frederick W. Horn, pg. 634

- "Janssen, Edward H. 1815 - 1877". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Lewis, Chelsey (October 30, 2020). "First he summited Everest, then this Cedarburg native crossed Wisconsin by foot, bike and kayak". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Milwaukee, WI. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- "Former Marquette Grid Coach Kenney Dies". Marshfield News-Herald. Marshfield, Wisconsin. Associated Press. November 30, 1950. p. 15. Retrieved August 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Heaphy, Leslie A.; May, Mel Anthony (2006). Encyclopedia of Women and Baseball. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. pp. 260. ISBN 0-7864-2100-2. LCCN 2006008719.

- "3 more Wisconsin players picked in baseball draft". jsonline.com. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- Ernst, Erik (June 28, 2012). "More from Cedarburg-native country star Josh Thompson on Wisconsin's country music community and behind-the-scenes life on the Country Throwdown Tour". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Milwaukee, WI. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

External links

- City of Cedarburg

- Cedarburg Chamber of Commerce

- Sanborn fire insurance maps: 1893 1900 1910

- A Walk Through Yesterday [historic building tour brochure]