Kaiseki

Kaiseki (懐石) or kaiseki-ryōri (懐石料理) is a traditional multi-course Japanese dinner. The term also refers to the collection of skills and techniques that allow the preparation of such meals and is analogous to Western haute cuisine.[1]

There are two kinds of traditional Japanese meal styles called kaiseki or kaiseki-ryōri. The first, where kaiseki is written as "会席" and kaiseki-ryōri as "会席料理", refers to a set menu of select food served on an individual tray (to each member of a gathering).[2] The second, written as "懐石" and as "懐石料理", refers to the simple meal that the host of a chanoyu gathering serves to the guests before a ceremonial tea,[2] and is also known as cha-kaiseki (茶懐石).[3] The development of nouvelle cuisine was likely inspired by kaiseki principles.[4][5]

Origin

The kanji characters used to write "kaiseki" (懐石) literally mean "breast-pocket stone". These kanji are thought to have been incorporated by Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591), to indicate the frugal meal served in the austere style of chanoyu (Japanese tea ceremony). The idea came from the practice where Zen monks would ward off hunger by putting warm stones into the front folds of their robes, near their stomachs.

Before these kanji started to be used, the kanji for writing the word were simply ones indicating that the cuisine was for a gathering (会席料理).[6] Both sets of kanji remain in use today to write the word; the authoritative Japanese dictionary 'Kōjien' describes kaiseki (literally, "cuisine for a gathering") as a banquet meal where the main beverage is sake (Japanese rice wine), and the "bosom-stone" cuisine as the simple meal served in chanoyu. To distinguish between the two in speech and if necessary in writing, the chanoyu meal may be referred to as "tea" kaiseki, or cha-kaiseki.[7][8]

Modern kaiseki draws on a number of traditional Japanese haute cuisines, notably the following four traditions: imperial court cuisine (有職料理, yūsoku ryōri), from the 9th century in the Heian period; Buddhist cuisine of temples (精進料理, shōjin ryōri), from the 12th century in the Kamakura period; samurai cuisine of warrior households (本膳料理, honzen ryōri), from the 14th century in the Muromachi period; and tea ceremony cuisine (茶懐石, cha kaiseki), from the 15th century in the Higashiyama period of the Muromachi period. All of these individual cuisines were formalized and developed over time, and continue in some form to the present day, but have also been incorporated into kaiseki cuisine. Different chefs weight these differently – court and samurai cuisine are more ornate, while temple and tea ceremony cuisine are more restrained.

Style

In the present day, kaiseki is a type of art form that balances the taste, texture, appearance, and colors of food.[7] To this end, only fresh seasonal ingredients are used and are prepared in ways that aim to enhance their flavor. Local ingredients are often included as well.[9] Finished dishes are carefully presented on plates that are chosen to enhance both the appearance and the seasonal theme of the meal. Dishes are beautifully arranged and garnished, often with real leaves and flowers, as well as edible garnishes designed to resemble natural plants and animals.

Order

Originally, kaiseki comprised a bowl of miso soup and three side dishes;[10] this is now instead the standard form of Japanese-style cuisine generally, referred to as a セット (setto, "set"). Kaiseki has since evolved to include an appetizer, sashimi, a simmered dish, a grilled dish and a steamed course,[10] in addition to other dishes at the discretion of the chef.[11]

- Sakizuke (先附): an appetizer similar to the French amuse-bouche.

- Hassun (八寸): the second course, which sets the seasonal theme. Typically one kind of sushi and several smaller side dishes. Traditionally served on a square dish measuring eight sun (寸) on each side.

- Mukōzuke (向付): a sliced dish of seasonal sashimi.

- Takiawase (煮合): vegetables served with meat, fish or tofu; the ingredients are simmered separately.

- Futamono (蓋物): a "lidded dish"; typically a soup.

- Yakimono (焼物): (1) flame-grilled food (esp. fish); (2) earthenware, pottery, china.

- Su-zakana (酢肴): a small dish used to cleanse the palate, such as vegetables in vinegar; vinegared appetizer.

- Suimono (吸い物): a soup, usually a clear broth with few accompaniments.

- Hiyashi-bachi (冷し鉢): served only in summer; chilled, lightly cooked vegetables.

- Naka-choko (中猪口): another palate-cleanser; may be a light, acidic soup.

- Shiizakana (強肴): a substantial dish, such as a hot pot.

- Gohan (御飯): a rice dish made with seasonal ingredients.

- Kō no mono (香の物): seasonal pickled vegetables.

- Tome-wan (止椀): a miso-based or vegetable soup served with rice.

- Mizumono (水物): a seasonal dessert; may be fruit, confection, ice cream, or cake.

Sakizuke (先附)

Sakizuke (先附) Hassun (八寸)

Hassun (八寸) Owan (お椀)

Owan (お椀) Otsukuri (お造り)

Otsukuri (お造り) Agemono (揚げ物)

Agemono (揚げ物) Futamono (蓋物)

Futamono (蓋物) Dai no mono (台の物)

Dai no mono (台の物) Gohan, Kō no mono, Tomewan (御飯・香の物・止椀)

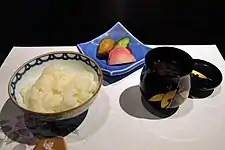

Gohan, Kō no mono, Tomewan (御飯・香の物・止椀) Mizumono (水物)

Mizumono (水物)

Cha-kaiseki

This is the meal served in the context of chanoyu (Japanese tea ceremony). It precedes the serving of the tea at a formal tea function (chaji). The basic constituents of a cha-kaiseki meal are the ichijū sansai or "one soup, three side dishes", and the rice, plus the following: suimono, hassun, yutō, and kōnomono. The one soup referred to here is usually suimono (clear soup) or miso soup and the basic three side dishes are the following:

- Mukōzuke: foods in a dish arranged on the far side of the meal tray for each guest, which is why it is called mukōzuke (lit., "set to the far side"). Often this might be some kind of sashimi, though not necessarily so. On the near side of the meal tray are arranged the rice and the soup, both in lacquered lidded bowls.

- Nimono (煮物): simmered foods, served in individual lidded bowls.

- Yakimono: grilled foods (usually some kind of fish), brought out in a serving dish for the guests to serve themselves.

Here under is a description of the additional items mentioned above:

- Suimono (吸物): clear soup served in a small lacquered and lidded bowl, to cleanse the palate before the exchange of sake (rice wine) between host and guests. Also referred to as kozuimono (small clear soup) or hashiarai (chopstick rinser).

- Hassun: a tray of tidbits from mountain and sea that the guests serve themselves to and accompanies the round of saké (rice wine) shared by host and guests.

- Yutō (湯桶): pitcher of hot water having slightly browned rice in it, which the guests serve to themselves.

- Kō no mono: pickles that accompany the yutō.

Extra items that may be added to the menu are generally referred to as shiizakana and these attend further rounds of sake. Because the host leaves them with the first guest, they are also referred to as azukebachi (lit., "bowl left in another's care").[12]

Casual kaiseki

Casual kaiseki meals theatrically arrange ingredients in dishes and combine rough textured pottery with fine patterned bowls or plates for effect. The bento box is another casual, common form of popular kaiseki.

Kaiseki locations

Kaiseki is often served in ryokan in Japan, but it is also served in small restaurants, known as ryōtei (料亭). Kyoto is well known for its kaiseki, as it was the home of the imperial court and nobility for over a millennium. In Kyoto, kaiseki-style cooking is sometimes known as Kyoto cooking (京料理, kyō-ryōri), to emphasize its traditional Kyoto roots, and includes some influence from traditional Kyoto home cooking, notably obanzai (おばんざい), the Kyoto term for sōzai (惣菜) or okazu (おかず).

Price

Kaiseki is often very expensive – kaiseki dinners at top traditional restaurants generally cost from 5,000 yen to upwards of 40,000 per person,[13] without drinks. Cheaper options are available, notably lunch (from around 4,000 to 8,000 yen (US$37 to $74), and in some circumstances bento (around 2,000 to 4,000 yen (US$18 to $37)). In some cases counter seating is cheaper than private rooms. At ryokan, the meals may be included in the price of the room or optional, and may be available only to guests, or served to the general public (some ryokan are now primarily restaurants). Traditional menu options offer three price levels, Sho Chiku Bai (traditional trio of pine, bamboo, and plum), with pine being most expensive, plum least expensive; this is still found at some restaurants.

See also

References

- Bourdain, Anthony (2001). A Cook's Tour: Global Adventures in Extreme Cuisines. New York: Ecco. ISBN 0-06-001278-1.

- Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, ISBN 4-7674-2015-6

- Japanese Kōjien dictionary

- McCarron, Meghan (7 September 2017). "The Japanese Origins of Modern Fine Dining". Eater. Vox Media. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Rosner, Helen (11 March 2019). "The Female Chef Making Japan's Most Elaborate Cuisine Her Own". The New Yorker. Conde Nast. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "From kaiseki 会席 to kaiseki 懐石: The Development of Formal Tea Cuisine" in Chanoyu Quarterly 50

- Furiya, Linda (2000-05-17). "The Art of Kaiseki". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- "Welcome to Kyoto - Kaiseki Ryori -". Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- Baker, Aryn (2007-06-14). "Kaiseki: Perfection On a Plate". Time. Archived from the original on June 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- Brenner, Leslie; Michalene Busico (2007-05-16). "The fine art of kaiseki". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- Murata, Yoshihiro; Kuma, Masashi; Adrià, Ferran (2006). Kaiseki: the exquisite cuisine of Kyoto's Kikunoi Restaurant. Kodansha International. p. 13. ISBN 4-7700-3022-3.

- Tsuji Kiichi. Tsujitome Cha-kaiseki, Ro-hen in the series Chanoyu jissen kōza. Tankosha, 1987.

- Kyoto-ryori, Kansai Food Page

Further reading

- Murata, Yoshihiro. Kaiseki: The Exquisite Cuisine of Kyoto's Kikunoi Restaurant. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2006. ISBN 4770030223. OCLC 67840174.

- Tsuji, Kaichi. Kaiseki: Zen Tastes in Japanese Cooking. Kodansha International, 1972; second printing, 1981.

- Tsutsui, Hiroichi. "From kaiseki 会席 to kaiseki 懐石: The Development of Formal Tea Cuisine". Chanoyu Quarterly no. 50 (Urasenke Foundation, 1987).

External links

- Furiya, Linda (2000-05-17). "The Art of Kaiseki". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- "Welcome to Kyoto - Kaiseki Ryori -". Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- Images of Kaiseki on Flickr

- Kyoto Travel Guide—Lists of Kyo Kaiseki Restaurants in Kyoto