Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel (French: Tunnel sous la Manche), also known as the Chunnel,[3][4] is a 50.46-kilometre (31.35 mi) underwater railway tunnel that connects Folkestone (Kent, England) with Coquelles (Pas-de-Calais, France) beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover. It is the only fixed link between the island of Great Britain and the European mainland. At its lowest point, it is 75 metres (246 ft) below the sea bed and 115 metres (377 ft) below sea level.[5][6][7] At 37.9 kilometres (23.5 mi), it has the longest underwater section of any tunnel in the world and is the third longest railway tunnel in the world. The speed limit for trains through the tunnel is 160 kilometres per hour (99 mph).[8] The tunnel is owned and operated by the company Getlink, formerly "Groupe Eurotunnel".

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | English Channel (Strait of Dover) |

| Coordinates | 51.0125°N 1.5041°E |

| Status | Active |

| Start | Folkestone, Kent, England, (51.0971°N 1.1558°E) |

| End | Coquelles, Pas-de-Calais, Hauts-de-France, France (50.9228°N 1.7804°E) |

| Operation | |

| Opened |

|

| Owner | Getlink |

| Operator | |

| Character | Passenger trains, freight trains, vehicle shuttle trains |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 50.46 km (31.35 mi) |

| No. of tracks | 2 single track tunnels 1 service tunnel |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrified | Overhead line, 25 kV 50 Hz AC, 5.87 m[1] |

| Operating speed | 160 km/h (99 mph) (track safety restrictions) 200 km/h (120 mph) (possible by track geometry, not yet allowed)[2] |

| Route map | |

Channel Tunnel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distances from Castle Hill Tunnel Portal Distances to terminals measured around terminal loops | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The tunnel carries high-speed Eurostar passenger trains, LeShuttle services for road vehicles[9] and freight trains.[10] It connects end-to-end with high-speed railway lines: the LGV Nord in France and High Speed 1 in England. In 2017, rail services carried 10.3 million passengers and 1.22 million tonnes of freight, and the Shuttle carried 10.4 million passengers, 2.6 million cars, 51,000 coaches, and 1.6 million lorries (equivalent to 21.3 million tonnes of freight),[11] compared with 11.7 million passengers, 2.6 million lorries and 2.2 million cars by sea through the Port of Dover.[12]

Plans to build a cross-Channel fixed link appeared as early as 1802,[13][14] but British political and media pressure motivated by fears of compromising national security had disrupted attempts to build one.[15] An early unsuccessful attempt was made in the late 19th century, on the English side, "in the hope of forcing the hand of the English Government".[16] The eventual successful project, organised by Eurotunnel, began construction in 1988 and opened in 1994. Estimated to cost £5.5 billion in 1985,[17] it was at the time the most expensive construction project ever proposed. The cost finally amounted to £9 billion (equivalent to £21.8 billion in 2021), well over budget.[18][19]

Since its opening, the tunnel has experienced mechanical problems. Both fires and cold weather have temporarily disrupted its operation.[20][21] Since at least 1997, aggregations of migrants around Calais seeking entry to the United Kingdom, such as through the tunnel, have prompted deterrence and countermeasures.[22][23][24]

Origins

Earlier proposals

- 1802: Albert Mathieu put forward a cross-Channel tunnel proposal.

- 1875: The Channel Tunnel Company Ltd[25] began preliminary trials

- 1882: The Abbot's Cliff heading had reached 897 yards (820 m) and that at Shakespeare Cliff was 2,040 yards (1,870 m) in length

- January 1975: A UK–France government-backed scheme, which started in 1974, was cancelled

- February 1986:The Treaty of Canterbury was signed, allowing the project to proceed

- June 1988: First tunnelling commenced in France

- December 1988: UK TBM commenced operation

- December 1990: Service tunnel broke through under the Channel

- May 1994: Tunnel formally opened by Queen Elizabeth II and President Mitterrand

- June 1994: Freight trains commenced operations

- November 1994: Passenger trains commenced operation

- November 1996: Fire in a heavy goods vehicle (HGV) shuttle severely damaged the tunnel

- November 2007: High Speed 1, linking London to the tunnel, opened

- September 2008: Another fire in an HGV shuttle severely damaged the tunnel

- December 2009: Eurostar trains stranded in the tunnel due to melting snow affecting the trains' electrical hardware

- November 2011: First commercial freight service run on High Speed 1

In 1802, Albert Mathieu-Favier, a French mining engineer, put forward a proposal to tunnel under the English Channel, with illumination from oil lamps, horse-drawn coaches, and an artificial island positioned mid-Channel for changing horses.[13] His design envisaged a bored two-level tunnel with the top tunnel used for transport and the bottom one for groundwater flows.[26]

In 1839, Aimé Thomé de Gamond, a Frenchman, performed the first geological and hydrographical surveys on the Channel between Calais and Dover. He explored several schemes and, in 1856, presented a proposal to Napoleon III for a mined railway tunnel from Cap Gris-Nez to East Wear Point with a port/airshaft on the Varne sandbank[27][28] at a cost of 170 million francs, or less than £7 million.[29]

In 1865, a deputation led by George Ward Hunt proposed the idea of a tunnel to the Chancellor of the Exchequer of the day, William Ewart Gladstone.[30]

In 1866, Henry Marc Brunel made a survey of the floor of the Strait of Dover. By his results, he proved that the floor was composed of chalk, like the adjoining cliffs, and thus a tunnel was feasible.[31] For this survey, he invented the gravity corer, which is still used in geology.

Around 1866, William Low and Sir John Hawkshaw promoted tunnel ideas,[32] but apart from preliminary geological studies,[33] none were implemented.

An official Anglo-French protocol was established in 1876 for a cross-Channel railway tunnel.

In 1881, British railway entrepreneur Sir Edward Watkin and Alexandre Lavalley, a French Suez Canal contractor, were in the Anglo-French Submarine Railway Company that conducted exploratory work on both sides of the Channel.[34][35] From June 1882 to March 1883, the British tunnel boring machine tunneled, through chalk, a total of 1,840 m (6,037 ft),[36] while Lavalley used a similar machine to drill 1,669 m (5,476 ft) from Sangatte on the French side.[37] However, the cross-Channel tunnel project was abandoned in 1883, despite this success, after fears raised by the British military that an underwater tunnel might be used as an invasion route.[36][38] Nevertheless, in 1883, this TBM was used to bore a railway ventilation tunnel—7 feet (2.1 m) in diameter and 6,750 feet (2,060 m) long—between Birkenhead and Liverpool, England, through sandstone under the Mersey River.[39] These early works were encountered more than a century later during the TML project.

A 1907 film, Tunnelling the English Channel by pioneer filmmaker Georges Méliès,[40] depicts King Edward VII and President Armand Fallières dreaming of building a tunnel under the English Channel.

In 1919, during the Paris Peace Conference, British prime minister David Lloyd George repeatedly brought up the idea of a Channel tunnel as a way of reassuring France about British willingness to defend against another German attack. The French did not take the idea seriously, and nothing came of the proposal.[41]

In the 1920s, Winston Churchill advocated for the Channel Tunnel, using that exact name in his essay "Should Strategists Veto The Tunnel?" It was published on 27 July 1924 in the Weekly Dispatch, and argued vehemently against the idea that the tunnel could be used by a Continental enemy in an invasion of Britain. Churchill expressed his enthusiasm for the project again in an article for the Daily Mail on 12 February 1936, "Why Not A Channel Tunnel?"[42]

There was another proposal in 1929, but nothing came of this discussion and the idea was shelved. Proponents estimated the construction cost at US$150 million. The engineers had addressed the concerns of both nations' military leaders by designing two sumps—one near the coast of each country—that could be flooded at will to block the tunnel but this did not appease military leaders, or dispel concerns about hordes of tourists who would disrupt English life.[43] Military fears continued during the Second World War. After the fall of France, as Britain prepared for an expected German invasion, a Royal Navy officer in the Directorate of Miscellaneous Weapons Development calculated that Hitler could use slave labour to build two Channel tunnels in 18 months. The estimate caused rumours that Germany had already begun digging.[44]

A British film from Gaumont Studios, The Tunnel (also called TransAtlantic Tunnel), was released in 1935 as a science-fiction project concerning the creation of a transatlantic tunnel. It referred briefly to its protagonist, a Mr. McAllan, as having completed a British Channel tunnel successfully in 1940, five years into the future of the film's release.

By 1955, defence arguments had become less relevant due to the dominance of air power, and both the British and French governments supported technical and geological surveys. In 1958 the 1881 workings were cleared in preparation for a £100,000 geological survey by the Channel Tunnel Study Group. 30% of the funding came from Channel Tunnel Co Ltd, the largest shareholder of which was the British Transport Commission, as successor to the South Eastern Railway.[45] A detailed geological survey was carried out in 1964 and 1965.[46]

Although the two countries agreed to build a tunnel in 1964, the phase 1 initial studies and signing of a second agreement to cover phase 2 took until 1973.[47] The plan described a government-funded project to create two tunnels to accommodate car shuttle wagons on either side of a service tunnel. Construction started on both sides of the Channel in 1974.

On 20 January 1975, to the dismay of their French partners, the then-governing Labour Party in Britain cancelled the project due to uncertainty about EEC membership, doubling cost estimates and the general economic crisis at the time. By this time the British tunnel boring machine was ready and the Ministry of Transport had conducted a 300 m (980 ft) experimental drive.[15] (This short tunnel, called Adit A1, was eventually reused as the starting and access point for tunnelling operations from the British side, and remains an access point to the service tunnel.) The cancellation costs were estimated at £17 million.[47] On the French side, a tunnel-boring machine had been installed underground in a stub tunnel. It lay there for 14 years until 1988, when it was sold, dismantled, refurbished and shipped to Turkey, where it was used to drive the Moda tunnel for the Istanbul Sewerage Scheme.

Initiation of project

In 1979, the "Mouse-hole Project" was suggested when the Conservatives came to power in Britain. The concept was a single-track rail tunnel with a service tunnel but without shuttle terminals. The British government took no interest in funding the project, but British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher did not object to a privately funded project, although she said she assumed it would be for cars rather than trains. In 1981, Thatcher and French president François Mitterrand agreed to establish a working group to evaluate a privately funded project. In June 1982 the Franco-British study group favoured a twin tunnel to accommodate conventional trains and a vehicle shuttle service. In April 1985 promoters were invited to submit scheme proposals. Four submissions were shortlisted:

- Channel Tunnel, a rail proposal based on the 1975 scheme presented by Channel Tunnel Group/France–Manche (CTG/F–M).

- Eurobridge, a 35-kilometre (22 mi) suspension bridge with a series of 5 km (3.1 mi) spans with a roadway in an enclosed tube.[48]

- Euroroute, a 21-kilometre (13 mi) tunnel between artificial islands approached by bridges.

- Channel Expressway, a set of large-diameter road tunnels with mid-Channel ventilation towers.[15]

The cross-Channel ferry industry protested under the name "Flexilink". In 1975 there was no campaign protesting a fixed link, with one of the largest ferry operators (Sealink) being state-owned. Flexilink continued rousing opposition throughout 1986 and 1987.[15] Public opinion strongly favoured a drive-through tunnel, but concerns about ventilation, accident management and driver mesmerisation led to the only shortlisted rail submission, CTG/F-M, being awarded the project in January 1986.[15] Reasons given for the selection included that it caused least disruption to shipping in the Channel and least environmental disruption, was the best protected against terrorism, and was the most likely to attract sufficient private finance.[49]

Arrangement

The British Channel Tunnel Group consisted of two banks and five construction companies, while their French counterparts, France–Manche, consisted of three banks and five construction companies. The banks' role was to advise on financing and secure loan commitments. On 2 July 1985, the groups formed Channel Tunnel Group/France–Manche (CTG/F–M). Their submission to the British and French governments was drawn from the 1975 project, including 11 volumes and a substantial environmental impact statement.[15]

The Anglo-French Treaty on the Channel Tunnel was signed by both governments in Canterbury Cathedral. The Treaty of Canterbury (1986) prepared the Concession for the construction and operation of the Fixed Link by privately owned companies and outlined arbitration methods to be used in the event of disputes. It set up the Intergovernmental Commission (IGC), responsible for monitoring all matters associated with the Tunnel's construction and operation on behalf of the British and French governments, and a Safety Authority to advise the IGC. It drew a land frontier between the two countries in the middle of the Channel tunnel—the first of its kind.[50][51][52]

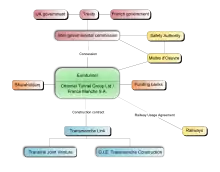

Design and construction were done by the ten construction companies in the CTG/F-M group. The French terminal and boring from Sangatte were done by the five French construction companies in the joint venture group GIE Transmanche Construction. The English Terminal and boring from Shakespeare Cliff were done by the five British construction companies in the Translink Joint Venture. The two partnerships were linked by a bi-national project organisation, TransManche Link (TML).[15] The Maître d'Oeuvre was a supervisory engineering body employed by Eurotunnel under the terms of the concession that monitored the project and reported to the governments and banks.[53]

In France, with its long tradition of infrastructure investment, the project had widespread approval. The French National Assembly approved it unanimously in April 1987, and after a public inquiry, the Senate approved it unanimously in June. In Britain, select committees examined the proposal, making history by holding hearings away from Westminster, in Kent. In February 1987, the third reading of the Channel Tunnel Bill took place in the House of Commons, and passed by 94 votes to 22. The Channel Tunnel Act gained Royal assent and passed into law in July.[15] Parliamentary support for the project came partly from provincial members of Parliament on the basis of promises of regional Eurostar through train services that never materialised; the promises were repeated in 1996 when the contract for construction of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link was awarded.[54]

Cost

The tunnel is a build-own-operate-transfer (BOOT) project with a concession.[55] TML would design and build the tunnel, but financing was through a separate legal entity, Eurotunnel. Eurotunnel absorbed CTG/F-M and signed a construction contract with TML, but the British and French governments controlled final engineering and safety decisions, now in the hands of the Channel Tunnel Safety Authority. The British and French governments gave Eurotunnel a 55-year operating concession (from 1987; extended by 10 years to 65 years in 1993)[49] to repay loans and pay dividends. A Railway Usage Agreement was signed between Eurotunnel, British Rail and SNCF guaranteeing future revenue in exchange for the railways obtaining half of the tunnel's capacity.

Private funding for such a complex infrastructure project was of unprecedented scale. Initial equity of £45 million was raised by CTG/F-M, increased by £206 million private institutional placement, £770 million was raised in a public share offer that included press and television advertisements, a syndicated bank loan and letter of credit arranged £5 billion.[15] Privately financed, the total investment costs at 1985 prices were £2.6 billion. At the 1994 completion actual costs were, in 1985 prices, £4.65 billion: an 80% cost overrun.[19] The cost overrun was partly due to enhanced safety, security, and environmental demands.[55] Financing costs were 140% higher than forecast.[56]

Construction

Working from both the English and French sides of the Channel, eleven tunnel boring machines or TBMs cut through chalk marl to construct two rail tunnels and a service tunnel. The vehicle shuttle terminals are at Cheriton (part of Folkestone) and Coquelles, and are connected to the English M20 and French A16 motorways respectively.

Tunnelling commenced in 1988, and the tunnel began operating in 1994.[57] In 1985 prices, the total construction cost was £4.65 billion (equivalent to £13 billion in 2015), an 80% cost overrun. At the peak of construction 15,000 people were employed with daily expenditure over £3 million.[9] Ten workers, eight of them British, were killed during construction between 1987 and 1993, most in the first few months of boring.[58][59][60]

Completion

A 50 mm (2.0 in) diameter pilot hole allowed the service tunnel to break through without ceremony on 30 October 1990.[61] On 1 December 1990, Englishman Graham Fagg and Frenchman Phillippe Cozette broke through the service tunnel with the media watching.[62] Eurotunnel completed the tunnel on time.[55] (A BBC TV television commentator called Graham Fagg "the first man to cross the Channel by land for 8000 years".) The two tunnelling efforts met each other with an offset of only 36.2 cm (14.3 in). A Paddington Bear soft toy was chosen by British tunnellers as the first item to pass through to their French counterparts when the two sides met.[63]

The tunnel was officially opened, one year later than originally planned, by Queen Elizabeth II and the French president, François Mitterrand, in a ceremony held in Calais on 6 May 1994. The Queen travelled through the tunnel to Calais on a Eurostar train, which stopped nose to nose with the train that carried President Mitterrand from Paris.[3] Following the ceremony President Mitterrand and the Queen travelled on Le Shuttle to a similar ceremony in Folkestone.[3] A full public service did not start for several months. The first freight train, however, ran on 1 June 1994 and carried Rover and Mini cars being exported to Italy.

The Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL), now called High Speed 1, runs 69 miles (111 km) from St Pancras railway station in London to the tunnel portal at Folkestone in Kent. It cost £5.8 billion. On 16 September 2003 the prime minister, Tony Blair, opened the first section of High Speed 1, from Folkestone to north Kent. On 6 November 2007, the Queen officially opened High Speed 1 and St Pancras International station,[64] replacing the original slower link to Waterloo International railway station. High Speed 1 trains travel at up to 300 km/h (186 mph), the journey from London to Paris taking 2 hours 15 minutes, to Brussels 1 hour 51 minutes.[65]

In 1994, the American Society of Civil Engineers elected the tunnel as one of the seven modern Wonders of the World.[66] In 1995, the American magazine Popular Mechanics published the results.[67]

Opening dates

The opening was phased for various services offered as the Channel Tunnel Safety Authority, the IGC, gave permission for various services to begin at several dates over the period 1994/1995 but start-up dates were a few days later.[68]

| Traffic flow | Start of service |

|---|---|

| HGV lorry shuttles | 19 May 1994[69] |

| Freight | 1 June 1994[69] |

| Eurostar passenger | 14 November 1994[70] |

| Car shuttles | 22 December 1994[71] |

| Coach shuttles | 26 June 1995[72] |

| Bicycle service | 10 August 1995[73] |

| Motorcycle service | 31 August 1995[74] |

| Caravan/campervan service | 30 September 1995[74] |

Engineering

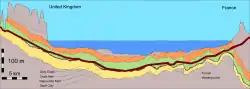

Site investigation undertaken in the 20 years before construction confirmed earlier speculations that a tunnel could be bored through a chalk marl stratum. The chalk marl is conducive to tunnelling, with impermeability, ease of excavation and strength. The chalk marl runs along the entire length of the English side of the tunnel, but on the French side a length of 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) has variable and difficult geology. The tunnel consists of three bores: two 7.6-metre (24 ft 11 in) diameter rail tunnels, 30 metres (98 ft) apart, 50 kilometres (31 mi) in length with a 4.8-metre (15 ft 9 in) diameter service tunnel in between. The three bores are connected by cross-passages and piston relief ducts. The service tunnel was used as a pilot tunnel, boring ahead of the main tunnels to determine the conditions. English access was provided at Shakespeare Cliff and French access from a shaft at Sangatte. The French side used five tunnel boring machines (TBMs), and the English side six. The service tunnel uses Service Tunnel Transport System (STTS) and Light Service Tunnel Vehicles (LADOGS). Fire safety was a critical design issue.

Between the portals at Beussingue and Castle Hill the tunnel is 50.5 kilometres (31 mi) long, with 3.3 kilometres (2 mi) under land on the French side and 9.3 kilometres (6 mi) on the UK side, and 37.9 kilometres (24 mi) under sea.[6] It is the third-longest rail tunnel in the world, behind the Gotthard Base Tunnel in Switzerland and the Seikan Tunnel in Japan, but with the longest under-sea section.[75] The average depth is 45 metres (148 ft) below the seabed.[76] On the UK side, of the expected 5 million cubic metres (6.5×106 cu yd) of spoil approximately 1 million cubic metres (1.3×106 cu yd) was used for fill at the terminal site, and the remainder was deposited at Lower Shakespeare Cliff behind a seawall, reclaiming 74 acres (30 ha)[9] of land.[77] This land was then made into the Samphire Hoe Country Park. Environmental impact assessment did not identify any major risks for the project, and further studies into safety, noise, and air pollution were overall positive. However, environmental objections were raised over a high-speed link to London.[78]

Geology

Successful tunnelling required a sound understanding of topography and geology and the selection of the best rock strata through which to dig. The geology of this site generally consists of northeasterly dipping Cretaceous strata, part of the northern limb of the Wealden-Boulonnais dome. Characteristics include:

- Continuous chalk on the cliffs on either side of the Channel containing no major faulting, as observed by Verstegan in 1605.

- Four geological strata, marine sediments laid down 90–100 million years ago; pervious upper and middle chalk above slightly pervious lower chalk and finally impermeable Gault Clay. A sandy stratum, glauconitic marl (tortia), is in between the chalk marl and gault clay.

- A 25–30-metre (82 ft 0 in – 98 ft 5 in) layer of chalk marl (French: craie bleue) in the lower third of the lower chalk appeared to present the best tunnelling medium. The chalk has a clay content of 30–40% providing impermeability to groundwater yet relatively easy excavation with strength allowing minimal support. Ideally, the tunnel would be bored in the bottom 15 metres (49 ft) of the chalk marl, allowing water inflow from fractures and joints to be minimised, but above the gault clay that would increase stress on the tunnel lining and swell and soften when wet.[79]

On the English side, the stratum dip is less than 5°; on the French side, this increases to 20°. Jointing and faulting are present on both sides. On the English side, only minor faults of displacement less than 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) exist; on the French side, displacements of up to 15 metres (49 ft 3 in) are present owing to the Quenocs anticlinal fold. The faults are of limited width, filled with calcite, pyrite and remolded clay. The increased dip and faulting restricted the selection of routes on the French side. To avoid confusion, microfossil assemblages were used to classify the chalk marl. On the French side, particularly near the coast, the chalk was harder, more brittle and more fractured than on the English side. This led to the adoption of different tunnelling techniques on the two sides.[80]

The Quaternary undersea valley Fosse Dangeard, and Castle Hill landslip at the English portal, caused concerns. Identified by the 1964–65 geophysical survey, the Fosse Dangeard is an infilled valley system extending 80 metres (262 ft) below the seabed, 500 metres (1,640 ft) south of the tunnel route in mid-channel. A 1986 survey showed that a tributary crossed the path of the tunnel, and so the tunnel route was made as far north and deep as possible. The English terminal had to be located in the Castle Hill landslip, which consists of displaced and tipping blocks of lower chalk, glauconitic marl and gault debris. Thus the area was stabilised by buttressing and inserting drainage adits.[80] The service tunnel acted as a pilot preceding the main ones, so that the geology, areas of crushed rock, and zones of high water inflow could be predicted. Exploratory probing took place in the service tunnel, in the form of extensive forward probing, vertical downward probes and sideways probing.[80]

Site investigation

Marine soundings and samplings by Thomé de Gamond were carried out during 1833–67, establishing the seabed depth at a maximum of 55 metres (180 ft) and the continuity of geological strata (layers). Surveying continued over many years, with 166 marine and 70 land-deep boreholes being drilled and over 4,000 line kilometres of the marine geophysical survey completed.[81] Surveys were undertaken in 1958–1959, 1964–1965, 1972–1974 and 1986–1988.

The surveying in 1958–59 catered for immersed tube and bridge designs, as well as a bored tunnel, and thus a wide area was investigated. At this time, marine geophysics surveying for engineering projects was in its infancy, with poor positioning and resolution from seismic profiling. The 1964–65 surveys concentrated on a northerly route that left the English coast at Dover harbour; using 70 boreholes, an area of deeply weathered rock with high permeability was located just south of Dover harbour.[81]

Given the previous survey results and access constraints, a more southerly route was investigated in the 1972–73 survey, and the route was confirmed to be feasible. Information for the tunnelling project also came from work before the 1975 cancellation. On the French side at Sangatte, a deep shaft with adits was made. On the English side at Shakespeare Cliff, the government allowed 250 metres (820 ft) of 4.5-metre (15 ft) diameter tunnel to be driven. The actual tunnel alignment, method of excavation and support were essentially the same as the 1975 attempt. In the 1986–87 survey, previous findings were reinforced, and the characteristics of the gault clay and the tunnelling medium (chalk marl that made up 85% of the route) were investigated. Geophysical techniques from the oil industry were employed.[81]

Tunnelling

.svg.png.webp)

Tunnelling was a major engineering challenge, with the only precedent being the undersea Seikan Tunnel in Japan, which opened in 1988. A serious health and safety risk with building tunnels underwater is major water inflow due to the high hydrostatic pressure from the sea above, under weak ground conditions. The tunnel also had the challenge of time: being privately funded, the early financial return was paramount.

The objective was to construct two 7.6-metre-diameter (25 ft) rail tunnels, 30 metres (98 ft) apart, 50 kilometres (31 mi) in length; a 4.8-metre-diameter (16 ft) service tunnel between the two main ones; pairs of 3.3-metre (10 ft 10 in)-diameter cross-passages linking the rail tunnels to the service one at 375-metre (1,230 ft) spacing; piston relief ducts 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) in diameter connecting the rail tunnels 250 metres (820 ft) apart; two undersea crossover caverns to connect the rail tunnels,[82] with the service tunnel always preceding the main ones by at least 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) to ascertain the ground conditions. There was plenty of experience with excavating through chalk in the mining industry, while the undersea crossover caverns were a complex engineering problem. The French one was based on the Mount Baker Ridge freeway tunnel in Seattle; the UK cavern was dug from the service tunnel ahead of the main ones, to avoid delay.

Precast segmental linings in the main TBM drives were used, but two different solutions were used. On the French side, neoprene and grout sealed bolted linings made of cast iron or high-strength reinforced concrete were used; on the English side, the main requirement was for speed so bolting of cast-iron lining segments was only carried out in areas of poor geology. In the UK rail tunnels, eight lining segments plus a key segment were used; in the French side, five segments plus a key.[83] On the French side, a 55-metre (180 ft) diameter 75-metre (246 ft) deep grout-curtained shaft at Sangatte was used for access. On the English side, a marshalling area was 140 metres (459 ft) below the top of Shakespeare Cliff, the New Austrian Tunnelling method (NATM) was first applied in the chalk marl here. On the English side, the land tunnels were driven from Shakespeare Cliff—the same place as the marine tunnels—not from Folkestone. The platform at the base of the cliff was not large enough for all of the drives and, despite environmental objections, tunnel spoil was placed behind a reinforced concrete seawall, on condition of placing the chalk in an enclosed lagoon, to avoid wide dispersal of chalk fines. Owing to limited space, the precast lining factory was on the Isle of Grain in the Thames estuary,[82] which used Scottish granite aggregate delivered by ship from the Foster Yeoman coastal super quarry at Glensanda in Loch Linnhe on the west coast of Scotland.

On the French side, owing to the greater permeability to water, earth pressure balance TBMs with open and closed modes was used. The TBMs were of a closed nature during the initial 5 kilometres (3 mi), but then operated as open, boring through the chalk marl stratum.[82] This minimised the impact to the ground, allowed high water pressures to be withstood and it also alleviated the need to grout ahead of the tunnel. The French effort required five TBMs: two main marine machines, one mainland machine (the short land drives of 3 km (2 mi) allowed one TBM to complete the first drive then reverse direction and complete the other), and two service tunnel machines. On the English side, the simpler geology allowed faster open-faced TBMs.[84] Six machines were used; all commenced digging from Shakespeare Cliff, three marine-bound and three for the land tunnels.[82] Towards the completion of the undersea drives, the UK TBMs were driven steeply downwards and buried clear of the tunnel. These buried TBMs were then used to provide an electrical earth. The French TBMs then completed the tunnel and were dismantled.[85] A 900 mm (35 in) gauge railway was used on the English side during construction.[86]

In contrast to the English machines, which were given technical names, the French tunnelling machines were all named after women: Brigitte, Europa, Catherine, Virginie, Pascaline, Séverine.[87]

At the end of the tunnelling, one machine was on display at the side of the M20 motorway in Folkestone until Eurotunnel sold it on eBay for £39,999 to a scrap metal merchant.[88] Another machine (T4 "Virginie") still survives on the French side, adjacent to Junction 41 on the A16, in the middle of the D243E3/D243E4 roundabout. On it are the words "hommage aux bâtisseurs du tunnel", meaning "tribute to the builders of the tunnel".

Tunnel boring machines

The eleven tunnel boring machines were designed and manufactured through a joint venture between the Robbins Company of Kent, Washington, United States; Markham & Co. of Chesterfield, England; and Kawasaki Heavy Industries of Japan.[89] The TBMs for the service tunnels and main tunnels on the UK side were designed and manufactured by James Howden & Company Ltd, Scotland.[90]

Railway design

Loading gauge

The loading gauge height is 5.75 m (18 ft 10 in).[91]

Communications

There are three communication systems:[92]

- Concession radio (CR) for mobile vehicles and personnel within Eurotunnel's Concession (terminals, tunnels, coastal shafts)

- Track-to-train radio (TTR) for secure speech and data between trains and the railway control centre

- Shuttle internal radio (SIR) for communication between shuttle crew and to passengers over car radios

Power supply

Power is delivered to the locomotives via an overhead line at 25 kV 50 Hz.[93][94] with a normal overhead clearance of 6.03 metres (19 ft 9+1⁄2 in).[95] All tunnel services run on electricity, shared equally from English and French sources. There are two substations fed at 400 kV at each terminal, but in an emergency, the tunnel's lighting (about 20,000 light fittings) and the plant can be powered solely from either England or France.[96]

The traditional railway south of London uses a 750 V DC third rail to deliver electricity, but since the opening of High Speed 1 there is no longer any need for tunnel trains to use it. High Speed 1, the tunnel and the LGV Nord all have power provided via overhead catenary at 25 kV 50 Hz. The railways on "classic" lines in Belgium are also electrified by overhead wires, but at 3000 V DC.[94]

Signalling

A cab signalling system gives information directly to train drivers on a display. There is a train protection system that stops the train if the speed exceeds that indicated on the in-cab display. TVM430, as used on LGV Nord and High Speed 1, is used in the tunnel.[97] The TVM signalling is interconnected with the signalling on the high-speed lines on either side, allowing trains to enter and exit the tunnel system without stopping. The maximum speed is 160 km/h (99 mph).[98]

Signalling in the tunnel is coordinated from two control centres: The main control centre at the Folkestone terminal, and a backup at the Calais terminal, which is staffed at all times and can take over all operations in the event of a breakdown or emergency.

Track system

Conventional ballasted tunnel track was ruled out owing to the difficulty of maintenance and lack of stability and precision. The Sonneville International Corporation's track system was chosen based on reliability and cost-effectiveness based on a good performance in Swiss tunnels and worldwide. The type of track used is known as Low Vibration Track (LVT). Like a ballasted track, the LVT is of the free-floating type, held in place by gravity and friction. Reinforced concrete blocks of 100 kg support the rails every 60 cm and are held by 12 mm thick closed-cell polymer foam pads placed at the bottom of rubber boots. The latter separates the blocks' mass movements from the lean encasement concrete. The ballastless track provides extra overhead clearance necessary for the passage of larger trains.[99] The corrugated rubber walls of the boots add a degree of isolation of horizontal wheel-rail vibrations and are insulators of the track signal circuit in the humid tunnel environment. UIC60 (60 kg/m) rails of 900A grade rest on 6 mm (0.2 in) rail pads, which fit the RN/Sonneville bolted dual leaf-springs. The rails, LVT-blocks and their boots with pads were assembled outside the tunnel, in a fully automated process developed by the LVT inventor, Mr. Roger Sonneville. About 334,000 Sonneville blocks were made on the Sangatte site.

Maintenance activities are less than projected. Initially, the rails were ground on a yearly basis or after approximately 100MGT of traffic. Ride quality continues to be noticeably smooth and of low noise. Maintenance is facilitated by the existence of two tunnel junctions or crossover facilities, allowing for two-way operation in each of the six tunnel segments, and providing safe access for maintenance of one isolated tunnel segment at a time. The two crossovers are the largest artificial undersea caverns ever built, at150 m long, 10 m high and 18 m wide. The English crossover is 8 km (5.0 mi) from Shakespeare Cliff, and the French crossover is 12 km (7.5 mi) from Sangatte.[100]

Ventilation, cooling and drainage

The ventilation system maintains the air pressure in the service tunnel higher than in the rail tunnels, so that in the event of a fire, smoke does not enter the service tunnel from the rail tunnels. Two cooling water pipes in each rail tunnel circulate chilled water to remove heat generated by the rail traffic. Pumping stations remove water in the tunnels from rain, seepage, and so on.[101]

During the design stage of the tunnel, engineers found that its aerodynamic properties and the heat generated by high-speed trains as they passed through it would raise the temperature inside the tunnel to 50 °C (122 °F).[102] As well as making the trains "unbearably warm" for passengers, this also presented a risk of equipment failure and track distortion.[102] To cool the tunnel to below 35 °C (95 °F), engineers installed 480 kilometres (300 mi) of 0.61 m (24 in) diameter cooling pipes carrying 84 million litres (18 million imperial gallons) of water. The network—Europe's largest cooling system—was supplied by eight York Titan chillers running on R22, a hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) refrigerant gas.[102][103]

Due to R22's ozone depletion potential (ODP) and high global warming potential (GWP), its use is being phased out in developed countries. Since 1 January 2015, it has been illegal in Europe to use HCFCs to service air-conditioning equipment; broken equipment that used HCFCs must be replaced with equipment that does not use it. In 2016, Trane was selected to provide replacement chillers for the tunnel's cooling network.[102] The York chillers were decommissioned and four "next generation" Trane Series E CenTraVac large-capacity (2600 kW to 14,000 kW) chillers were installed—two in Sangatte, France, and two at Shakespeare Cliff, UK. The energy-efficient chillers, using Honeywell's non-flammable, ultra-low GWP R1233zd(E) refrigerant, maintain temperatures at 25 °C (77 °F), and in their first year of operation generated savings of 4.8 GWh—approximately 33%, equating to €500,000 ($585,000)—for tunnel operator Getlink.[103]

Rolling stock

| Class | Image | Type | Cars per set | Top speed | Number | Routes | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | |||||||

| Eurotunnel | ||||||||

| Class 9 |  |

Electric locomotive | Car Shuttle: 2 x 28 HGV Shuttle: 2 x 30 or 32 |

99 | 160 | 57 | Folkestone to Calais | 1992–2003 |

| Car Shuttle |  |

Passenger carriage | 99 | 160 | 252 | |||

| HGV Shuttle |  |

Passenger carriage | 99 | 160 | 430 | |||

| Club car |  |

Passenger carriage | ||||||

| Eurostar | ||||||||

| Class 373 Eurostar e300 |

|

EMU | 2 x 18 | 186 | 300 | 28 | London–Paris London–Brussels London–Marne-la-Vallée – Chessy London–Bourg Saint Maurice London–Marseille Saint-Charles |

1992-1996 |

| Class 374 Eurostar e320 |

|

EMU | 16 | 200 | 320 | 17 | London–Paris London–Marne-la-Vallée – Chessy London–Amsterdam Centraal |

2011-2018 |

| Freight: DB Cargo | ||||||||

| Class 92 |  |

Electric locomotive | 1 | 87 | 140 | 46 | Freight Routes between the United Kingdom to France. | 1993–1996 |

| Eurotunnel Service Locomotives | ||||||||

| Class 0001 |  |

Diesel locomotive | 1 | 62 | 100 | 10 | Shunting | 1991–1992 |

| Class 0031 | Diesel locomotive | 1 | 31 | 50 | 11 | 1988 (as 900 mm gauge locomotive); 1993-1994 (rebuilt as shunter) | ||

Rolling stock used previously

| Class | Picture | Nickname/Nameplate | Production | Builder | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNCF Class BB 22200/British Rail Class 22 |  |

Yellow Submarine | 1976–1986 | Alstom | Electric locomotives used in 1994/95 pending delivery of Class 9s[104][105] |

| British Rail Class 319 | .jpg.webp) |

1987 | York Carriage Works | Electric Multiple Unit used on demonstration runs in 1993/94[106] |

Operators

LeShuttle

Getlink operates the LeShuttle, a vehicle shuttle service, through the tunnel.

Car shuttle sets have two separate halves: single and double deck. Each half has two loading/unloading wagons and 12 carrier wagons. Eurotunnel's original order was for nine car shuttle sets.

Heavy goods vehicle (HGV) shuttle sets also have two halves, with each half containing one loading wagon, one unloading wagon and 14 carrier wagons. There is a club car behind the leading locomotive, where drivers must stay during the journey. Eurotunnel originally ordered six HGV shuttle sets.

Initially 38 LeShuttle locomotives were commissioned, with one at each end of a shuttle train.

Freight locomotives

Forty-six Class 92 locomotives for hauling freight trains and overnight passenger trains (the Nightstar project, which was abandoned) were commissioned, running on both overhead AC and third-rail DC power. However, RFF does not let these run on French railways, so there are plans to certify Alstom Prima II locomotives for use in the tunnel.[107]

International passenger

Thirty-one Eurostar trains, based on the French TGV, built to UK loading gauge with many modifications for safety within the tunnel, were commissioned, with ownership split between British Rail, French national railways (SNCF) and Belgian national railways (NMBS/SNCB). British Rail ordered seven more for services north of London.[108] Around 2010, Eurostar ordered ten trains from Siemens based on its Velaro product. The Class 374 entered service in 2016 and has been operating through the Channel Tunnel ever since alongside the current Class 373.

Germany (DB) has since around 2005 tried to get permission to run train services to London. At the end of 2009, extensive fire-proofing requirements were dropped and DB received permission to run German Intercity-Express (ICE) test trains through the tunnel. In June 2013 DB was granted access to the tunnel, but these plans were ultimately dropped.[109][110]

In October 2021, Renfe, the Spanish state railway company, expressed interest in operating a cross-Channel route between Paris and London using some of their existing trains with the intention of competing with Eurostar. No details have been revealed as to which trains would be used.[111]

Service locomotives

Diesel locomotives for rescue and shunting work are Eurotunnel Class 0001 and Eurotunnel Class 0031.

Operation

The following chart presents the estimated number of passengers and tonnes of freight, respectively, annually transported through the Channel Tunnel since 1994 (M = million).

Usage and services

Transport services offered by the tunnel are as follows:

- Eurotunnel Le Shuttle roll-on roll-off shuttle service for road vehicles and their drivers and passengers,

- Eurostar passenger trains,

- through freight trains.[10]

Both the freight and passenger traffic forecasts that led to the construction of the tunnel were overestimated; in particular, Eurotunnel's commissioned forecasts were over-predictions.[112] Although the captured share of Channel crossings was forecast correctly, high competition (especially from budget airlines which expanded rapidly in the 1990s and 2000s) and reduced tariffs led to low revenue. Overall cross-Channel traffic was overestimated.[113][114]

With the EU's liberalisation of international rail services, the tunnel and High Speed 1 have been open to competition since 2010. There have been a number of operators interested in running trains through the tunnel and along High Speed 1 to London. In June 2013, after several years, DB obtained a license to operate Frankfurt – London trains, not expected to run before 2016 because of delivery delays of the custom-made trains.[115] Plans for the service to Frankfurt seem to have been shelved in 2018.[116]

Passenger traffic volumes

Cross-tunnel passenger traffic volumes peaked at 18.4 million in 1998, dropped to 14.9 million in 2003 and has increased substantially since then.[117]

At the time of the decision about building the tunnel, 15.9 million passengers were predicted for Eurostar trains in the opening year. In 1995, the first full year, actual numbers were a little over 2.9 million, growing to 7.1 million in 2000, then dropping to 6.3 million in 2003. Eurostar was initially limited by the lack of a high-speed connection on the British side. After the completion of High Speed 1 in two stages in 2003 and 2007, traffic increased. In 2008, Eurostar carried 9,113,371 passengers, a 10% increase over the previous year, despite traffic limitations due to the 2008 Channel Tunnel fire.[118] Eurostar passenger numbers continued to increase.

| Year | Passengers transported | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Eurostar[A] (actual ticket sales)[119][120] |

Passenger Shuttles (estimated, millions)[113][119] |

Total (estimated, millions) | |

| 1994 | ~100,000[113] | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| 1995 | 2,920,309 | 4.4 | 7.3 |

| 1996 | 4,995,010 | 7.9 | 12.9 |

| 1997 | 6,004,268 | 8.6 | 14.6 |

| 1998 | 6,307,849 | 12.1 | 18.4 |

| 1999 | 6,593,247 | 11.0 | 17.6 |

| 2000 | 7,130,417 | 9.9 | 17.0 |

| 2001 | 6,947,135 | 9.4 | 16.3 |

| 2002 | 6,602,817 | 8.6 | 15.2 |

| 2003 | 6,314,795 | 8.6 | 14.9 |

| 2004 | 7,276,675 | 7.8 | 15.1 |

| 2005 | 7,454,497 | 8.2 | 15.7 |

| 2006 | 7,858,337 | 7.8 | 15.7 |

| 2007 | 8,260,980 | 7.9 | 16.2 |

| 2008 | 9,113,371 | 7.0 | 16.1 |

| 2009 | 9,220,233 | 6.9 | 16.1 |

| 2010 | 9,528,558 | 7.5 | 17.0 |

| 2011 | 9,679,764 | 9.3 | 19.0 |

| 2012 | 9,911,649 | 10.0 | 19.9 |

| 2013[117] | 10,132,691 | 10.3 | 20.4 |

| 2014[117] | 10,397,894 | 10.6 | 21.0 |

| 2015[117] | 10,399,267 | 10.5 | 20.9 |

| 2016[121] | 10,011,337 | 10.6 | 20.6 |

| 2017[122] | 10,300,622 | 10.4 | 20.7 |

| 2018[123] | 11,000,000 | ||

| 2019[124] | 11,046,608 | ||

| 2020[124] | 2,503,419 | ||

|

A only passengers taking Eurostar to cross the Channel | |||

Freight traffic volumes

Freight volumes have been erratic, with a major decrease during 1997 due to a closure caused by a fire in a freight shuttle. Freight crossings increased over the period, indicating the substitutability of the tunnel by sea crossings. The tunnel has achieved a market share close to or above Eurotunnel's 1980s predictions but Eurotunnel's 1990 and 1994 predictions were overestimates.[125]

For through freight trains, the first year prediction was 7.2 million tonnes; the actual 1995 figure was 1.3M tonnes.[112] Through freight volumes peaked in 1998 at 3.1M tonnes. This fell back to 1.21M tonnes in 2007, increasing slightly to 1.24M tonnes in 2008.[118] Together with that carried on freight shuttles, freight growth has occurred since opening, with 6.4M tonnes carried in 1995, 18.4M tonnes recorded in 2003[113] and 19.6M tonnes in 2007.[119] Numbers fell back in the wake of the 2008 fire.

| Year | Freight transported (tonnes) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| through freight trains | Eurotunnel Truck Shuttles (est.)[113][117][119] |

Total (est.) | |

| 1994 | 0 | 800,000 | 800,000 |

| 1995[120] | 1,349,802 | 5,100,000 | 6,400,000 |

| 1996[120] | 2,783,774 | 6,700,000 | 9,500,000 |

| 1997[120] | 2,925,171 | 3,300,000 | 6,200,000 |

| 1998[120] | 3,141,438 | 9,200,000 | 12,300,000 |

| 1999[120] | 2,865,251 | 10,900,000 | 13,800,000 |

| 2000[120] | 2,947,385 | 14,700,000 | 17,600,000 |

| 2001[120] | 2,447,432 | 15,600,000 | 18,000,000 |

| 2002[120] | 1,463,580 | 15,600,000 | 17,100,000 |

| 2003[126] | 1,743,686 | 16,700,000 | 18,400,000 |

| 2004[127] | 1,889,175 | 16,600,000 | 18,500,000 |

| 2005[127] | 1,587,790 | 17,000,000 | 18,600,000 |

| 2006[128] | 1,569,429 | 16,900,000 | 18,500,000 |

| 2007[128] | 1,213,647 | 18,400,000 | 19,600,000 |

| 2008[129] | 1,239,445 | 14,200,000 | 15,400,000 |

| 2009[129] | 1,181,089 | 10,000,000 | 11,200,000 |

| 2010[117][130] | 1,128,079 | 14,200,000 | 15,300,000 |

| 2011[131] | 1,324,673 | 16,400,000 | 17,700,000 |

| 2012[132] | 1,227,139 | 19,000,000 | 20,200,000 |

| 2013[133] | 1,363,834 | 17,700,000 | 19,100,000 |

| 2014[134] | 1,648,047 | 18,700,000 | 20,350,000 |

| 2015[117] | 1,420,000 | 19,300,000 | 20,720,000 |

| 2016[121] | 1,040,000 | 21,300,000 | 22,340,000 |

| 2017[122] | 1,220,000 | 21,300,000 | 22,550,000 |

| 2018[135] | 1,301,460 | ||

| 2019[124] | 1,390,303 | ||

| 2020[124] | 1,138,213 | ||

Eurotunnel's freight subsidiary is Europorte 2.[136] In September 2006 EWS, the UK's largest rail freight operator, announced that owing to the cessation of UK-French government subsidies of £52 million per annum to cover the tunnel "Minimum User Charge" (a subsidy of around £13,000 per train, at a traffic level of 4,000 trains per annum), freight trains would stop running after 30 November.[137]

Economic performance

Shares in Eurotunnel were issued at £3.50 per share on 9 December 1987. By mid-1989 the price had risen to £11.00. Delays and cost overruns led to the price dropping; during demonstration runs in October 1994, it reached an all-time low. Eurotunnel suspended payment on its debt in September 1995 to avoid bankruptcy.[138] In December 1997 the British and French governments extended Eurotunnel's operating concession by 34 years, to 2086. The financial restructuring of Eurotunnel occurred in mid-1998, reducing debt and financial charges. Despite the restructuring, The Economist reported in 1998 that to break even Eurotunnel would have to increase fares, traffic and market share for sustainability.[139] A cost-benefit analysis of the tunnel indicated that there were few impacts on the wider economy and few developments associated with the project and that the British economy would have been better off if it had not been constructed.[113][140]

Under the terms of the Concession, Eurotunnel was obliged to investigate a cross-Channel road tunnel. In December 1999 road and rail tunnel proposals were presented to the British and French governments, but it was stressed that there was not enough demand for a second tunnel.[141] A three-way treaty between the United Kingdom, France and Belgium governs border controls, with the establishment of control zones wherein the officers of the other nation may exercise limited customs and law enforcement powers. For most purposes, these are at either end of the tunnel, with the French border controls on the UK side of the tunnel and vice versa. For some city-to-city trains, the train is a control zone.[142] A binational emergency plan coordinates UK and French emergency activities.[143]

In 1999 Eurostar posted its first net profit, having made a loss of £925m in 1995.[57] In 2005 Eurotunnel was described as being in a serious situation.[144] In 2013, operating profits rose 4 percent from 2012, to £54 million.[145]

Security

There is a need for full passport controls, as the tunnel acts as a border between the Schengen Area and the Common Travel Area. There are juxtaposed controls, meaning that passports are checked before boarding by officials of the departing country, and on arrival by officials of the destination country. These control points are only at the main Eurostar stations: French officials operate at London St Pancras, Ebbsfleet International and Ashford International, while British officials operate at Calais-Fréthun, Lille-Europe, Marne-la-Vallée–Chessy, Brussels-South and Paris-Gare du Nord. There are security checks before boarding as well. For the shuttle road-vehicle trains, there are juxtaposed passport controls before boarding the trains.

For Eurostar trains originating south of Paris, there is no passport and security check before departure, and those trains must stop in Lille at least 30 minutes to allow all passengers to be checked. No checks are performed on board. There have been plans for services from Amsterdam, Frankfurt and Cologne to London, but a major reason to cancel them was the need for a stop in Lille. Direct service from London to Amsterdam started on 4 April 2018; following the building of check-in terminals at Amsterdam and Rotterdam and the intergovernmental agreement, a direct service from the two Dutch cities to London started on 30 April 2020.[146]

Terminals

The terminals' sites are at Cheriton (near Folkestone in the United Kingdom) and Coquelles (near Calais in France). The UK site uses the M20 motorway for access. The terminals are organised with the frontier controls juxtaposed with the entry to the system to allow travellers to go onto the motorway at the destination country immediately after leaving the shuttle.

To achieve design output at the French terminal, the shuttles accept cars on double-deck wagons; for flexibility, ramps were placed inside the shuttles to provide access to the top decks.[147] At Folkestone there are 20 kilometres (12 mi) of the main-line track, 45 turnouts and eight platforms. At Calais there are 30 kilometres (19 mi) of track and 44 turnouts. At the terminals, the shuttle trains traverse a figure eight to reduce uneven wear on the wheels.[148] There is a freight marshalling yard west of Cheriton at Dollands Moor Freight Yard.

Regional impact

A 1996 report from the European Commission predicted that Kent and Nord-Pas de Calais had to face increased traffic volumes due to the general growth of cross-Channel traffic and traffic attracted by the tunnel. In Kent, a high-speed rail line to London would transfer traffic from road to rail.[149] Kent's regional development would benefit from the tunnel, but being so close to London restricts the benefits. Gains are in the traditional industries and are largely dependent on the development of Ashford International railway station, without which Kent would be totally dependent on London's expansion. Nord-Pas-de-Calais enjoys a strong internal symbolic effect of the Tunnel which results in significant gains in manufacturing.[150]

The removal of a bottleneck by means like the tunnel does not necessarily induce economic gains in all adjacent regions. The image of a region being connected to European high-speed transport and active political response is more important for regional economic development. Some small-medium enterprises located in the immediate vicinity of the terminal have used the opportunity to re-brand the profile of their business with positive effects, such as The New Inn at Etchinghill which was able to commercially exploit its unique selling point as being 'the closest pub to the Channel Tunnel'. Tunnel-induced regional development is small compared to general economic growth.[151] The South East of England is likely to benefit developmentally and socially from faster and cheaper transport to continental Europe, but the benefits are unlikely to be equally distributed throughout the region. The overall environmental impact is almost certainly negative.[152]

Since the opening of the tunnel, small positive impacts on the wider economy have been felt, but it is difficult to identify major economic successes directly attributed to the tunnel.[153] The Eurotunnel does operate profitably, offering an alternative transportation mode unaffected by poor weather.[154] High costs of construction did delay profitability, however, and companies involved in the tunnel's construction and operation early in operation relied on government aid to deal with the accumulated debt.[155][156][157]

Illegal immigration

Illegal immigrants and would-be asylum seekers have used the tunnel to attempt to enter Britain. By 1997, the problem had attracted international press attention, and by 1999, the French Red Cross opened the first migrant centre at Sangatte, using a warehouse once used for tunnel construction; by 2002, it housed up to 1,500 people at a time, most of them trying to get to the UK.[158] In 2001, most came from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Iran, but African countries were also represented.[159]

Eurotunnel, the company that operates the crossing, said that more than 37,000 migrants were intercepted between January and July 2015.[160] Approximately 3,000 migrants, mainly from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Sudan and Afghanistan, were living in the temporary camps erected in Calais at the time of an official count in July 2015.[161] An estimated 3,000 to 5,000 migrants were waiting in Calais for a chance to get to England.[162]

Britain and France operate a system of juxtaposed controls on immigration and customs, where investigations happen before travel. France is part of the Schengen immigration zone, removing border checks in normal times between most EU member states; Britain and the Republic of Ireland form their own separate Common Travel Area immigration zone.

Most illegal immigrants and would-be asylum seekers who got into Britain found some way to ride a freight train. Trucks are loaded onto freight trains. In a few instances, migrants stowed away in a liquid chocolate tanker and managed to survive, spread across several attempts.[163] Although the facilities were fenced, airtight security was deemed impossible; migrants would even jump from bridges onto moving trains. In several incidents people were injured during the crossing; others tampered with railway equipment, causing delays and requiring repairs.[164] Eurotunnel said it was losing £5m per month because of the problem.[165]

In 2001 and 2002, several riots broke out at Sangatte, and groups of migrants (up to 550 in a December 2001 incident) stormed the fences and attempted to enter en masse.[166]

Other migrants seeking permanent UK settlement use the Eurostar passenger train. They may purport to be visitors (whether to be issued with a required visit visa, or deny and falsify their true intentions to obtain a maximum of 6-months-in-a-year at-port stamp); purport to be someone else whose documents they hold, or used forged or counterfeit passports.[167] Such breaches result in refusal of permission to enter the UK, affected by Border Force after such a person's identity is fully established, assuming they persist in their application to enter the UK.[168]

Diplomatic efforts

Local authorities in both France and the UK called for the closure of the Sangatte migrant camp, and Eurotunnel twice sought an injunction against the centre.[158] As of 2006 the United Kingdom blamed France for allowing Sangatte to open, and France blamed both the UK for its then lax asylum rules/law, and the EU for not having a uniform immigration policy.[165] The problem's cause célèbre nature even lead to journalists being detained as they followed migrants onto railway property.[169]

In 2002, the European Commission told France that it was in breach of European Union rules on the free transfer of goods because of the delays and closures as a result of its poor security. The French government built a double fence, at a cost of £5 million, reducing the numbers of migrants detected each week reaching Britain on goods trains from 250 to almost none.[170] Other measures included CCTV cameras and increased police patrols.[171] At the end of 2002, the Sangatte centre was closed after the UK agreed to absorb some migrants.[172][173]

On 23 and 30 June 2015,[174] striking workers associated with MyFerryLink damaged sections of track by burning car tires, cancelling all trains and creating a backlog of vehicles. Hundreds seeking to reach Britain attempted to stow away inside and underneath transport trucks destined for the UK. Extra security measures included a £2 million upgrade of detection technology, £1 million extra for dog searches, and £12 million (over three years) towards a joint fund with France for security surrounding the Port of Calais.

Illegal attempts to cross and deaths

In 2002, a dozen migrants died in crossing attempts.[158] In the two months from June to July 2015, ten migrants died near the French tunnel terminal, during a period when 1,500 attempts to evade security precautions were being made each day.[175][176]

On 6 July 2015, a migrant died while attempting to climb onto a freight train while trying to reach Britain from the French side of the Channel.[177] The previous month an Eritrean man was killed under similar circumstances.[178]

During the night of 28 July 2015, one person, aged 25–30, was found dead after a night in which 1,500–2,000 migrants had attempted to enter the Eurotunnel terminal.[179] The body of a Sudanese migrant was subsequently found inside the tunnel.[180] On 4 August 2015, another Sudanese migrant walked nearly the entire length of one of the tunnels. He was arrested close to the British side, after having walked about 30 miles (48 km) through the tunnel.[181]

Mechanical incidents

Fires

There have been three fires in the tunnel, all on the heavy goods vehicle (HGV) shuttles, that were significant enough to close the tunnel, as well as other minor incidents.

On 9 December 1994, during an "invitation only" testing phase, a fire broke out in a Ford Escort car while its owner was loading it onto the upper deck of a tourist shuttle. The fire started at about 10:00, with the shuttle train stationary in the Folkestone terminal, and was put out about 40 minutes later with no passenger injuries.[182]

On 18 November 1996, a fire broke out on an HGV shuttle wagon in the tunnel, but nobody was seriously hurt. The exact cause is unknown,[183] although it was neither a Eurotunnel equipment nor rolling stock problem; it may have been due to arson of a heavy goods vehicle. It is estimated that the heart of the fire reached 1,000 °C (1,800 °F), with the tunnel severely damaged over 46 metres (151 ft), with some 500 metres (1,640 ft) affected to some extent. Full operation recommenced six months after the fire.[184]

On 21 August 2006, the tunnel was closed for several hours when a truck on an HGV shuttle train caught fire.[185][186]

On 11 September 2008, a fire occurred in the Channel Tunnel at 13:57 GMT. The incident started on an HGV shuttle train travelling towards France.[187] The event occurred 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from the French entrance to the tunnel. No one was killed but several people were taken to hospitals suffering from smoke inhalation, and minor cuts and bruises. The tunnel was closed to all traffic, with the undamaged South Tunnel reopening for limited services two days later.[188] Full service resumed on 9 February 2009[189] after repairs costing €60 million.

On 29 November 2012, the tunnel was closed for several hours after a truck on an HGV shuttle caught fire.[190]

On 17 January 2015, both tunnels were closed following a lorry fire that filled the midsection of Running Tunnel North with smoke. Eurostar cancelled all services.[191] The shuttle train had been heading from Folkestone to Coquelles and stopped adjacent to cross-passage CP 4418 just before 12:30 UTC. 38 passengers and four members of Eurotunnel staff were evacuated into the service tunnel and transported to France in special STTS road vehicles. They were taken to the Eurotunnel Fire/Emergency Management Centre close to the French portal.[192]

Train failures

On the night of 19/20 February 1996, about 1,000 passengers became trapped in the Channel Tunnel when Eurostar trains from London broke down owing to failures of electronic circuits caused by snow and ice being deposited and then melting on the circuit boards.[193]

On 3 August 2007, an electrical failure lasting six hours caused passengers to be trapped in the tunnel on a shuttle.[194]

On the evening of 18 December 2009, during the December 2009 European snowfall, five London-bound Eurostar trains failed inside the tunnel, trapping 2,000 passengers for approximately 16 hours, during the coldest temperatures in eight years.[195] A Eurotunnel spokesperson explained that snow had evaded the train's winterisation shields,[196] and the transition from cold air outside to the tunnel's warm atmosphere had melted the snow, resulting in electrical failures.[197][198][199][200] One train was turned back before reaching the tunnel; two trains were hauled out of the tunnel by Eurotunnel Class 0001 diesel locomotives. The blocking of the tunnel led to the implementation of Operation Stack, the transformation of the M20 motorway into a linear car park.[201]

The occasion was the first time that a Eurostar train was evacuated inside the tunnel; the failing of four at once was described as "unprecedented".[202] The Channel Tunnel reopened the following morning.[203] Nirj Deva, Member of the European Parliament for South East England, had called for Eurostar chief executive Richard Brown to resign over the incidents.[204] An independent report by Christopher Garnett (former CEO of Great North Eastern Railway) and Claude Gressier (a French transport expert) on the 18/19 December 2009 incidents was issued in February 2010, making 21 recommendations.[205][206]

On 7 January 2010, a Brussels–London Eurostar broke down in the tunnel. The train had 236 passengers on board and was towed to Ashford; other trains that had not yet reached the tunnel were turned back.[207][208]

Safety

The Channel Tunnel Safety Authority is responsible for some aspects of safety regulation in the tunnel; it reports to the Intergovernmental Commission (IGC).[209]

Channel Tunnel safety | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The service tunnel is used for access to technical equipment in cross-passages and equipment rooms, to provide fresh-air ventilation and for emergency evacuation. The Service Tunnel Transport System (STTS) allows fast access to all areas of the tunnel. The service vehicles are rubber-tired with a buried wire guidance system. The 24 STTS vehicles are used mainly for maintenance but also for firefighting and emergencies. "Pods" with different purposes, up to a payload of 2.5–5 tonnes (2.8–5.5 tons), are inserted into the side of the vehicles. The vehicles cannot turn around within the tunnel and are driven from either end. The maximum speed is 80 km/h (50 mph) when the steering is locked. A fleet of 15 Light Service Tunnel Vehicles (LADOGS) was introduced to supplement the STTSs. The LADOGS has a short wheelbase with a 3.4 m (11 ft) turning circle, allowing two-point turns within the service tunnel. Steering cannot be locked like the STTS vehicles, and maximum speed is 50 km/h (31 mph). Pods up to 1 tonne (1.1 tons) can be loaded onto the rear of the vehicles. Drivers in the tunnel sit on the right, and the vehicles drive on the left. Owing to the risk of French personnel driving on their native right side of the road, sensors in the vehicles alert the driver if the vehicle strays to the right side.[210]

The three tunnels contain 6,000 tonnes (6,600 tons) of air that needs to be conditioned for comfort and safety. Air is supplied from ventilation buildings at Shakespeare Cliff and Sangatte, with each building capable of providing 100% standby capacity. Supplementary ventilation also exists on either side of the tunnel. In the event of a fire, ventilation is used to keep smoke out of the service tunnel and move smoke in one direction in the main tunnel to give passengers clean air. The tunnel was the first main-line railway tunnel to have special cooling equipment. Heat is generated from traction equipment and drag. The design limit was set at 30 °C (86 °F), using a mechanical cooling system with refrigeration plants on both sides that run chilled water circulating in pipes within the tunnel.[211]

Trains travelling at high speed create piston effect pressure changes that can affect passenger comfort, ventilation systems, tunnel doors, fans and the structure of the trains, and which drag on the trains.[211] Piston relief ducts of 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) diameter were chosen to solve the problem, with 4 ducts per kilometre to give close to optimum results. However, this design led to extreme lateral forces on the trains, so a reduction in train speed was required and restrictors were installed in the ducts.[212]

The safety issue of a possible fire on a passenger-vehicle shuttle garnered much attention, with Eurotunnel noting that fire was the risk attracting the most attention in a 1994 safety case for three reasons: the opposition of ferry companies to passengers being allowed to remain with their cars; Home Office statistics indicating that car fires had doubled in ten years; and the long length of the tunnel. Eurotunnel commissioned the UK Fire Research Station—now part of the Building Research Establishment—to give reports of vehicle fires, and liaised with Kent Fire Brigade to gather vehicle fire statistics over one year. Fire tests took place at the French Mines Research Establishment with a mock wagon used to investigate how cars burned.[213] The wagon door systems are designed to withstand fire inside the wagon for 30 minutes, longer than the transit time of 27 minutes. Wagon air conditioning units help to purge dangerous fumes from inside the wagon before travel. Each wagon has a fire detection and extinguishing system, with sensing of ions or ultraviolet radiation, smoke and gases that can trigger halon gas to quench a fire. Since the HGV wagons are not covered, fire sensors are located on the loading wagon and in the tunnel. A 10-inch (250 mm) water main in the service tunnel provides water to the main tunnels at 125-metre (410 ft) intervals.[214] The ventilation system can control smoke movement. Special arrival sidings accept a train that is on fire, as the train is not allowed to stop whilst on fire in the tunnel unless continuing its journey would lead to a worse outcome. Eurotunnel has banned a wide range of hazardous goods from travelling in the tunnel. Two STTS (Service Tunnel Transportation System)[215] vehicles with firefighting pods are on duty at all times, with a maximum delay of 10 minutes before they reach a burning train.[184]

Unusual traffic

Trains

In 1999, the Kosovo Train for Life passed through the tunnel en route to Pristina, in Kosovo.

Other

In 2009, former F1 racing champion John Surtees drove a Ginetta G50 EV electric sports car prototype from England to France, using the service tunnel, as part of a charity event. He was required to keep to the 50-kilometre-per-hour (30 mph) speed limit.[216] To celebrate the 2014 Tour de France's transfer from its opening stages in Britain to France in July of that year, Chris Froome of Team Sky rode a bicycle through the service tunnel, becoming the first solo rider to do so.[217][218] The crossing took under an hour, reaching speeds of 65 kilometres per hour (40 mph)—faster than most cross-channel ferries.[219]

Mobile network coverage

Since 2012, French operators Bouygues Telecom, Orange and SFR have covered Running Tunnel South, the tunnel bore normally used for travel from France to Britain.

In January 2014, UK operators EE and Vodafone signed ten-year contracts with Eurotunnel for Running Tunnel North. The agreements will enable both operators' subscribers to use 2G and 3G services. Both EE and Vodafone planned to offer LTE services on the route; EE said it expected to cover the route with LTE connectivity by the summer of 2014. EE and Vodafone will offer Channel Tunnel network coverage for travellers from the UK to France. Eurotunnel said it also held talks with Three UK but has yet to reach an agreement with the operator.[220]

In May 2014, Eurotunnel announced that they had installed equipment from Alcatel-Lucent to cover Running Tunnel North and simultaneously to provide mobile service (GSM 900/1800 MHz and UMTS 2100 MHz) by EE, O2 and Vodafone. The service of EE and Vodafone commenced on the same date as the announcement. O2 service was expected to be available soon afterwards.[221]

In November 2014, EE announced that it had previously switched on LTE earlier in September 2014.[222] O2 turned on 2G, 3G and 4G services in November 2014, whilst Vodafone's 4G was due to go live later.[223]

Other (non-transport) services

The tunnel also houses the 1,000 MW ElecLink interconnector to transfer power between the British and French electricity networks. During the night of 31 August/1 September 2021,[224] the 51km-long 320 kV DC cable was switched into service for the first time.

See also

References

- Institution of Civil Engineers (Great Britain) (1995). The Channel Tunnel: Transport systems, Volume 4. Vol. 108. Thomas Telford. p. 22. ISBN 9780727720245.

- The Channel Tunnel: Terminals. Thomas Telford. 1993. ISBN 978-0-7277-1939-3.

- "On This Day – 1994: President and Queen open Chunnel". BBC News. 6 May 1994. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- Baraniuk, Chris (23 August 2017). "The Channel Tunnel that was never built". BBC. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "Folkestone Eurotunnel Trains". Transworld Leisure Limited. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Institute of Civil Engineers p. 95

- Wise, Jeff (1 October 2009). "Turkey Building the World's Deepest Immersed Tube Tunnel". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014.

- Dumitrache, Alina (24 March 2010). "The Channel Tunnel – Traveling Under the Sea". AutoEvolution. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Anderson, pp. xvi–xvii

- Chisholm, Michael (1995). Britain on the edge of Europe. London: Routledge. p. 151. ISBN 0-415-11921-9.

- "Traffic figures". GetLink Group. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "About/Performance". Port of Dover. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Whiteside p. 17

- "The Channel Tunnel". library.thinkquest.org. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- Wilson pp. 14–21

- Paddy at Home ("Chez Paddy") (2nd ed.). Chapman & Hall Covent Garden, London. 1887.

- Veditz, Leslie Allen. "The Channel Tunnel – A Case Study" (PDF). Fort McNair, Washington, D.C., U.S.: The Industrial College of the Armed Forces, National Defense University. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "How the Channel Tunnel was Built". Folkestone, England / Coquelles Cedex France: Eurotunnel Group. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

It was at the time the most expensive construction project ever proposed and the cost finally came in at £9 billion.

- Flyvbjerg et al. p. 12

- "Channel tunnel fire worst in service's history". The Guardian. 12 September 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Thousands freed from Channel Tunnel after trains fail". BBC News. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Four men caught in Channel Tunnel". BBC News. 4 January 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- "Sangatte refugee camp". The Guardian. UK. 23 May 2002. Retrieved 19 July 2009.