Chatham County, North Carolina

Chatham County (locally /ˈtʃætəm/ CHAT-əm)[1] is a county located in the Piedmont area of the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is also the location of the geographic center of North Carolina, northwest of Sanford.[2] As of the 2020 census, the population was 76,285.[3] Its county seat is Pittsboro.[4]

Chatham County | |

|---|---|

_6.jpg.webp) Chatham County Courthouse in Pittsboro | |

Flag  Seal  Logo | |

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 35°42′N 79°16′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1771 |

| Named for | William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham |

| Seat | Pittsboro |

| Largest community | Siler City |

| Area | |

| • Total | 708.93 sq mi (1,836.1 km2) |

| • Land | 681.68 sq mi (1,765.5 km2) |

| • Water | 27.25 sq mi (70.6 km2) 3.84% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 76,285 |

| • Estimate (2022) | 79,864 |

| • Density | 111.91/sq mi (43.21/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 9th |

| Website | www |

Chatham County is part of the Durham-Chapel Hill, NC Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is also included in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill Combined Statistical Area, which has a population of 2,043,867 as of 2020 census.

History

_18.jpg.webp)

Some of the first European settlers of what would become the county were English Quakers, who settled along the Haw and Eno rivers.[5] The county was formed in 1771 from Orange County. It had been named in 1758 for William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, who served as British Prime Minister from 1766 to 1768 and opposed harsh colonial policies. In 1907, parts of Chatham County and Moore County were combined to form Lee County.

The county did not have a county seat until 1778 when Chatham Courthouse was built. It was not until 1787 that it was renamed Pittsboro In 1781, Chatham Courthouse was located the south side of Robeson Creek, where the Horton Middle school is currently located. The Chatham Courthouse was the site of an engagement during the American Revolution on July 17, 1781. On July 16, 1781, Patriot leaders had tried and sentenced to hang several Loyalist leaders. Hearing of their fate, Loyalist leader Colonel David Fanning and his men encircled Chatham Courthouse and took 53 prisoners including Colonel Ambrose Ramsey, some local militia, and three members of the North Carolina General Assembly.[6]

While not devoted to large plantations, the county was developed for small farms, where slave labor was integral to the owners' productivity and success. By 1860 one-third of the county population were African Americans, chiefly enslaved.[7]

George Moses Horton, Historic Poet Laureate of Chatham County, (1798–1883) lived most of his life enslaved on a farm in Chatham County, moving North after emancipation. In one period he would write poems on commission for students at University of North Carolina after delivering produce to the campus. It was the first money he earned from his poems. He is among the few poets to have published his work while still held as a slave.[8][9][10]

Moncure, located at the confluence of the Deep and Haw rivers forming the Cape Fear River, once served as the westernmost inland port in the state. Steamships could travel between it and the Atlantic Coast along that major river.[11]

After the Civil War and emancipation, white violence against freedmen increased in an assertion of white supremacy and enforced dominance after emancipation. From the late 1860s secret terrorist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, Constitutional Union Guard, and White Brotherhood were active against blacks in the county.[7] After Reconstruction and into the early 20th century, a total of six lynchings of African Americans were recorded here. Harriet Finch, Jerry Finch, Lee Tyson, John Pattishall on September 30, 1885. Harriet Finch is 1 of only 4 lynchings of women to occur in North Carolina. Henry Jones was lynched on January 12, 1899, after being accused of raping and murdering Nancy Welch/Welsh, a white widow in Chatham County. The sixth person to be lynched was Eugene Daniel who was hanged and then had his body riddled with bullets on September 18, 1921.[12][13]

There was a notorious mass lynching of four African Americans on September 29, 1885, who were taken from the county jail in Pittsboro by a disguised mob at 1 am. The mob of 50–100 people hanged and killed Jerry Finch, his wife Harriet, and Lee Tyson, arrested for a robbery/murder.[7] Harriet Finch was one of four black women to be lynched in the state.[14] They also hanged John Pattishall, who was awaiting trial for two other unrelated robbery/murders.[7][15] Afterward, the editor of The Chatham Record strongly condemned the lynchings.[15] The county had the second-highest total of lynchings in the state, a number equaled by two other counties in this period.[16]

On March 25, 2010, the Chatham County Courthouse, built in 1881 in the county seat of Pittsboro, caught fire while undergoing renovations. It has now been rebuilt.

Coal mining

Spanning the southern border of Chatham County, the Deep River Coal Field contains the only known potentially economic bituminous coal deposits in the state. Coal was mined here on an artisan scale in colonial times. It was commercially produced beginning from the early 1850s.

The communities of Carbonton and Cumnock (formerly called Egypt in Lee County) developed with the coal mining industry. Much of the coal mined in the field during the Civil War was used for Confederate operations.[17]

The Coal Glen mine disaster of the 1920s, frequent flooding by the Deep River, the depth of the coal seam, and faulting of the seam sealed the fate of the mines. Production ceased in 1953.[18][19]

Agriculture and industry

The county was long dependent on agriculture as the basis of the economy, and there were numerous subsistence farmers in historic times. The area's natural soil conditions (composed mostly of the hard red clay soil common to the Piedmont) did not support the cultivation of commodity cash crops such as tobacco; this was never important in the county's economy. As a result, settlers held fewer slaves than in some areas of the state, but by 1860 enslaved African Americans constituted about one-third of the county population.[7] The production of livestock has always been more important to the county, especially the breeding of cattle and poultry.

The county once had a thriving dairy industry, but in recent years most farms have been sold and developed. The county is one of the state leaders in the poultry industry. Forage crops such as hay are also grown in large quantities in the county. Carolina Farm Stewardship Association has been housed in Chatham County, along with many organic agriculture farmers, including Councilman Farms and Phillips Dairy Farms.

Industrial growth in the county has been focused around the Siler City and Moncure areas of the county, with Moncure dominating. Companies in that area include, Progress Energy, Boise Cascade, Honeywell, and Arauco. Brick manufacturing, which makes use of the local red clay soil, has been an important economic factor in the Moncure area, with several brick plants operating there and in Brickhaven.

3M operates a greenstone mine south of Pittsboro along US 15-501. Greenstone is processed to manufacture roofing-shingle granules. In 2007, residents opposed to industrialization successfully blocked a similar quarry from being developed in the western part of the county.

The scenic rural environment has attracted many artists (Chatham Artists Guild), and arts-related tourism is a growing economic influence.

Chatham County has a deep tradition in southern music. Tommy Thompson, of the Red Clay Ramblers, and Tommy Edwards have entertained for decades with traditional, old time and bluegrass. Artists in many styles of music have emerged, from rock and roll to big band. Of late, Shakori Hills Grassroots Festival of Music and Dance hosts various styles of music. A four-day outdoor festival is held twice each year, in April and October. Artists who have performed at Shakori Hills include Patty Loveless, Ralph Stanley, Hugh Masekela, Donna the Buffalo, Carolina Chocolate Drops, Avett Brothers and Jim Lauderdale. Shakori Hills is also the location of the Hoppin John Fiddlers Convention and Mountain Aid benefit concert.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 708.93 square miles (1,836.1 km2), of which 681.68 square miles (1,765.5 km2) is land and 27.25 square miles (70.6 km2) (3.84%) is water.[20]

The county lies totally within the Piedmont physiographic region. The topography of the county is generally gently rolling with several higher hills rising above the general terrain. One of these hills, Terrells Mountain, on the Orange County line is the transmitter site for several radio and TV stations for the Raleigh-Durham market, including WUNC-TV 4, WDCG (G105), WNCB (B93.9), and WUNC 91.5 FM (NC Public Radio).

The county lies within the Cape Fear River drainage basin. The Cape Fear River begins in the county near the community of Moncure, at the confluence of the Haw River and the Deep River below Jordan Lake. B. Everett Jordan Lake, a major reservoir and flood-control lake, is located within the New Hope River basin and lies mainly in eastern Chatham County. The lake is owned by the US Army Corps of Engineers and is partially leased by the state of North Carolina as Jordan Lake State Recreation Area.

Much of the eastern part of the county lies within the Triassic Basin, a subregion of the Piedmont. Much of the bedrock in the county is volcanic in origin and formed during the Triassic period (hence the name). The Triassic origins have led to the formation of coal deposits in the southern part of the county. The Boren Clay Products Pit just north of Gulf in extreme southern Chatham County is a place where Triassic flora fossils persist.[21][22] The volcanic origins also led to the creation of high amounts of metamorphic-based rocks in the county. The county lies on the Carolina Slate Belt. Soils in the county are mostly clay based and have a deep red color, as do most soils in the Piedmont. Groundwater in the county is generally full of minerals and tends to be "hard" if not softened. Mineral-based water was the attraction at Mt. Vernon Springs during the latter part of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century. A resort spa was established at the mineral springs. Visitors would drink the water in the hopes of curing ailments and diseases. The resort closed in the early 20th century and is now gone. The springs are still there and are maintained by a local church.

Major water bodies

- B. Everett Jordan Lake

- Bear Creek

- Brush Creek

- Cape Fear River

- Deep River

- Harlands Creek

- Haw River

- Landrum Creek

- Little Brush Creek

- Loves Creek

- New Hope Creek

- Roberson Creek

- Rocky River

- Shearon Harris Reservoir

- Tick Creek

- Varnell Creek

- Wilkinson Creek

Adjacent counties

- Durham County – north

- Orange County – north

- Alamance County – north

- Wake County – east

- Harnett County – southeast

- Lee County – south

- Moore County – south

- Randolph County – west

Parks and recreation

In addition to those mentioned below, the communities of Pittsboro, Siler City, and Goldston operate parks and other recreation facilities.[23][24]

State parks, game land, trails, and recreation areas

- Chatham Game Land[25]

- Deep River State Trail

- Harris Game Land (part)[25]

- Jordan Game Land (part)[25]

- Jordan Lake Educational State Forest

- Jordan Lake State Recreation Area (including Crosswinds Campground, Ebenezer Church, Parker's Creek, Poplar Point, Seaforth area, Vista Point, Robeson Creek, New Hope Overlook, and White Oak Recreation Areas)

- Lee Game Land (part)[25]

- Lower Haw River State Natural Area

- Robeson Creek Boat Access

- Robeson Creek Paddle Access

County parks, trails, and recreation areas

- 15-501 Haw River Canoe Access

- American Tobacco Trail

- Briar Chapel Sports Park

- Bynum Beach Haw River Paddle Access

- Earl Thompson Park

- Northeast District Park

- Northwest District Park

- Southeast District Park

- Southwest Community Park

- US 64 Haw River Paddle Access

Other attractions

- Carnivore Preservation Trust

- Condoret Nature Preserve

- Crosswinds Marina

- Deep River Park and the Deep River Camelback Truss Bridge

- Irvin Nature Preserve

- La Grange Riparian Reserve

- McIver Landing

- New Hope Valley Railway

- Shakori Hills Grassroots Festival

- White Pines Nature Preserve (part)

- Wood's Mill Bend

Demographics

After the late 19th century lynchings in the county, and the state's disenfranchisement of blacks at the end of the century, many African Americans left in the Great Migration, as may be seen in population decreases at the beginning of the 20th century.

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 9,161 | — | |

| 1800 | 11,861 | 29.5% | |

| 1810 | 12,977 | 9.4% | |

| 1820 | 12,661 | −2.4% | |

| 1830 | 15,405 | 21.7% | |

| 1840 | 16,242 | 5.4% | |

| 1850 | 18,449 | 13.6% | |

| 1860 | 19,101 | 3.5% | |

| 1870 | 19,723 | 3.3% | |

| 1880 | 23,453 | 18.9% | |

| 1890 | 25,413 | 8.4% | |

| 1900 | 23,912 | −5.9% | |

| 1910 | 22,635 | −5.3% | |

| 1920 | 23,814 | 5.2% | |

| 1930 | 24,177 | 1.5% | |

| 1940 | 24,726 | 2.3% | |

| 1950 | 25,392 | 2.7% | |

| 1960 | 26,785 | 5.5% | |

| 1970 | 29,554 | 10.3% | |

| 1980 | 33,415 | 13.1% | |

| 1990 | 38,759 | 16.0% | |

| 2000 | 49,329 | 27.3% | |

| 2010 | 63,505 | 28.7% | |

| 2020 | 76,285 | 20.1% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 79,864 | [3] | 4.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] 1790–1960[27] 1900–1990[28] 1990–2000[29] 2010[30] 2020[3] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 53,087 | 69.59% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 7,768 | 10.18% |

| Native American | 173 | 0.23% |

| Asian | 1,616 | 2.12% |

| Pacific Islander | 24 | 0.03% |

| Other/Mixed | 3,245 | 4.25% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 10,372 | 13.6% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 76,285 people, 30,674 households, and 21,406 families residing in the county.

2010 census

At the 2010 census, there were 63,505 people and 24,877 households residing in the county.[32] The population density was 93.1 people per square mile (35.9 people/km2). There were 28,753 housing units at an average density of 39 units per square mile (15 units/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 76.0% White, 13.2% Black or African American, 0.5% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 7.1% from other races, and 1.9% from two or more races. 13.0% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

The median income for a household in the county was $56,038. The per capita income for the county was $29,991. About 12.2% of the population were below the poverty line.

In 2000, there were 19,741 households, out of which 28.80% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.30% were married couples living together, 10.00% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.80% were non-families. 24.50% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.00% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47 and the average family size was 2.91.

In 2000, the age distribution of the county was 22.50% under the age of 18, 7.30% from 18 to 24, 30.40% from 25 to 44, 24.60% from 45 to 64, and 15.30% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females there were 96.80 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.80 males.

A census tract within the county containing two affluent retirement communities had the highest average lifespan in the United States—97.5 years—according to data provided by the National Center for Health Statistics.[33][34]

Government and politics

_3.jpg.webp)

A five-member Board of Commissioners governs Chatham County. The commissioners are elected at large, but must reside within a particular district. Members of the Chatham County Board of Commissioners are elected for four-year terms, but the terms are staggered so that all five seats are not up for election at the same time.

At a Presidential level, Chatham County leans Democratic: no Republican presidential nominee has carried Chatham County since Ronald Reagan’s 1984 landslide, although John Kerry came within six votes of losing the county in 2004, and no candidate from either major party has obtained less than thirty-five percent of the county's vote since the three-way 1968 election when Richard Nixon managed to carry the county with merely 36.2% of the vote. Before 1960, Chatham was basically a typical "Solid South" county, only voting Republican in 1928 due to opposition to Al Smith’s Roman Catholic faith, and in 1900 – although in 1892 it was along with Nash and Sampson counties one of three counties in the state to give a plurality of its ballots to Populist James B. Weaver.

Chatham County is represented in the North Carolina Senate by Democrat Natalie Murdock in the 20th district and in the North Carolina House of Representatives by Democrat Robert Reives in the 54th district.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 21,186 | 43.59% | 26,787 | 55.12% | 626 | 1.29% |

| 2016 | 17,105 | 42.92% | 21,065 | 52.86% | 1,679 | 4.21% |

| 2012 | 16,665 | 47.03% | 18,361 | 51.82% | 408 | 1.15% |

| 2008 | 14,668 | 44.61% | 17,862 | 54.32% | 350 | 1.06% |

| 2004 | 12,892 | 49.73% | 12,897 | 49.75% | 133 | 0.51% |

| 2000 | 10,248 | 48.96% | 10,461 | 49.98% | 222 | 1.06% |

| 1996 | 7,731 | 42.03% | 9,353 | 50.84% | 1,312 | 7.13% |

| 1992 | 6,568 | 35.36% | 9,520 | 51.25% | 2,489 | 13.40% |

| 1988 | 6,999 | 47.81% | 7,600 | 51.92% | 40 | 0.27% |

| 1984 | 8,595 | 53.39% | 7,458 | 46.33% | 46 | 0.29% |

| 1980 | 5,414 | 41.00% | 7,144 | 54.10% | 647 | 4.90% |

| 1976 | 4,279 | 39.90% | 6,397 | 59.65% | 49 | 0.46% |

| 1972 | 6,175 | 62.12% | 3,624 | 36.46% | 142 | 1.43% |

| 1968 | 3,845 | 36.22% | 3,532 | 33.27% | 3,239 | 30.51% |

| 1964 | 4,111 | 43.71% | 5,295 | 56.29% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 4,308 | 47.91% | 4,683 | 52.09% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 3,729 | 47.32% | 4,151 | 52.68% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 3,606 | 45.59% | 4,303 | 54.41% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 2,008 | 34.65% | 3,396 | 58.60% | 391 | 6.75% |

| 1944 | 2,431 | 38.67% | 3,856 | 61.33% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 1,829 | 31.24% | 4,025 | 68.76% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 2,182 | 33.29% | 4,373 | 66.71% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1932 | 2,590 | 37.47% | 4,263 | 61.68% | 59 | 0.85% |

| 1928 | 3,318 | 55.32% | 2,680 | 44.68% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 2,755 | 44.32% | 3,446 | 55.44% | 15 | 0.24% |

| 1920 | 2,906 | 47.70% | 3,186 | 52.30% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1916 | 1,501 | 44.75% | 1,839 | 54.83% | 14 | 0.42% |

| 1912 | 70 | 2.28% | 1,652 | 53.86% | 1,345 | 43.85% |

Elected Officials

| Office[36][37] | Holder | Party | Term expires |

|---|---|---|---|

| Register of Deeds | Lunday Riggsbee | Democratic | 2024 |

| Sheriff | Mike Roberson | Democratic | 2022 |

| District 1 County Commissioner (chair) | Karen Howard | Democratic | 2024 |

| District 2 County Commissioner (vice chair) | Mike Dasher | Democratic | 2024 |

| District 3 County Commissioner | Diana Hales | Democratic | 2022 |

| District 4 County Commissioner | Jim Crawford | Democratic | 2022 |

| District 5 County Commissioner | Franklin Gomez Flores | Unaffiliated | 2024 |

Commissioners appoint a county manager who administers the day-to-day business of the county, including personnel and budget oversight. The Board of Commissioners also appoints the county attorney, clerk to the board of commissioners who is responsible for meeting agendas and minutes, and the tax administrator who manages all tax office functions, but they do not appoint other county staff positions.

The Board of Commissioners does have general authority over county policies, but several other boards have authority over specific policy areas, such as the Board of Health, Board of Social Services, Board of Elections and Soil and Water Conservation District Board. The Board of Commissioners appoints all members of the Board of Health and makes some of the appointments to the Board of Social Services, but neither the Board of Elections nor the Soil and Water District Conservation Board have any commissioner appointments.

Chatham County is a member of the regional Triangle J Council of Governments.[38]

Education

Chatham County contributes funds to, but does not govern, K-12 public education and the community college system. The Chatham County School System is governed by its own elected board. There are four public high schools: Seaforth in Pittsboro,Northwood in Pittsboro, Jordan-Matthews in Siler City, and Chatham Central in Bear Creek.

Chatham is home to three charter schools – Woods Charter School,[39] Chatham Charter High School, and Willow Oak Montessori Charter School.

Woods Charter School is a grade K-12 public school. The school moved into a new fully equipped building on 160 Woodland Grove Lane outside Pittsboro in August 2008. Woods ranked "top ten" on SAT scores in North Carolina.

Chatham Charter High School is a grade K-12 public school. The school is located on 2200 Hamp Stone Road in Siler City, NC.

Willow Oak Montessori Charter School is a tuition-free public school located in Central Chatham County, that currently serves children in grades 1 through 8.

Central Carolina Community College, which has two campuses in the county, is governed by its own appointed Board of Trustees.

Generally, county resources provide only part of the total funding for K-12 and community colleges, but the county devotes a considerable amount of its resources to public education. In fiscal year 2007–08, more than 39% of the county's tax dollars went to education.

According to the N.C. Association of County Commissioners Annual Tax and Budget Survey for fiscal year 2006–07, the county ranked 11th in the state in total spending per student and fifth in the percent of the current expense/general funds spent on schools per student. The county also was 14th in overall education resources per capita during fiscal year 06–07.

Transportation

Chatham County has managed to retain its rural character in part because it is not served by an Interstate Highway. However, Chatham County plays an important role in regional transportation due to its close proximity to the geographic center of North Carolina and to major cities such as Raleigh, Durham and Greensboro. Though driving is the dominant mode due to the county's rural nature, residents enjoy a number of transportation options.[40]

Major highways

The main east–west artery serving Chatham County is U.S. 64, which provides access to Siler City and Pittsboro. U.S. Routes 421 and 15–501 run in a north–south direction through the county; U.S. 421 serves Siler City and U.S. 15–501 serves Pittsboro. During the 1990s and early 2000s, the NCDOT invested more than one hundred million dollars upgrading U.S. 64, U.S. 421 and U.S. 15–501, which had previously been two-lane roads, to multi-lane highways. There is now a U.S. 64 bypass north of Pittsboro; a similar freeway diverts traffic on U.S. 421 east of Siler City.

Transit

Chatham County is served by two public transit providers – Chatham Transit Network and Chapel Hill Transit. Chatham Transit Network (CTN) is the Community Transportation Program for Chatham County, providing fixed route and human service transportation. CTN's fixed route provides weekday service between Siler City, Pittsboro and Chapel Hill.

Chatham County provides many scenic bike routes along the county's rural highways. The American Tobacco Trail also traverses the northeast corner of the county.

Nearby Raleigh–Durham International Airport (RDU) serves Chatham County. Siler City Municipal Airport (5W8) is located 3 miles (4.8 km) southwest of downtown Siler City. This public access airport is home to several single and multiengine airplanes.

The county is served by both Norfolk Southern Railway and CSX Transportation. Norfolk Southern serves Siler City, Bonlee, Bear Creek, and Goldston as a part of a spur line that runs between Greensboro and Sanford. CSX serves the Moncure area on trackage that runs between Raleigh and Hamlet. Oddly enough, Pittsboro was once served by the Seaboard System Railroad (the predecessor to CSX), but the tracks were taken up in the 1970s and were never to return.

Media

Newspapers

- Chatham County Events (online events calendar, blog, web series, business directory, summer camp guide, and park and playground map)[41]

- The Chatham County News

- Chatham Journal (weekly, based in Pittsboro)[42]

- The Chatham News (weekly, based in Siler City)[43]

- The Chatham Record (weekly, based Pittsboro)[44]

- Chatham County Line (published 10 times annually)[45]

Television

- WTVD (ABC affiliate)

- WRAL-TV (NBC affiliate)

- WGHP (FOX affiliate) High Point

- WNCN (CBS affiliate) Raleigh-Durham

- WFMY (CBS affiliate) Greensboro

- WRAZ (FOX affiliate) Raleigh-Durham

- WLFL (CW affiliate)

- WRDC (MyNetwork affiliate)

- WUNC (PBS affiliate)

- WUVC (Univision affiliate—Spanish language)

- WRPX (ION affiliate)

Representation in other media

The PBS documentary, Family Name, explored the history of families known to have both black and white branches, in these cases begun by white men fathering children with enslaved women. (Many free African-American families date to unions in the colonial era in Virginia between white women and African or African-American men.)[46] Their children were born into slavery, and the racial caste system classified them as black and enslaved regardless of proportion of white ancestry. Chatham County was referred to in the program, as men of the local Alston family had fathered children with slaves. As result there are Alston descendants who were classified as either African American, or white.[47][48]

Communities

Towns

- Apex (mostly in Wake County)

- Bennett

- Cary (mostly in Wake County)

- Chapel Hill (mostly in Orange County)

- Goldston

- Pittsboro (county seat)

- Siler City (largest community)

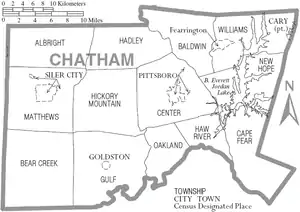

Townships

- Albright

- Baldwin

- Bear Creek

- Cape Fear

- Center

- Gulf

- Hadley

- Haw River

- Hickory Mountain

- Matthews

- New Hope

- Oakland

- Williams

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

See also

- List of counties in North Carolina

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Chatham County, North Carolina

- Haw River Valley AVA, wine region partially located in the county

References

- Talk Like A Tar Heel Archived 2013-06-22 at the Wayback Machine, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- "Geographic Center of the United States" (PDF). pubs.usgs.gov. September 3, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Chatham County, North Carolina". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Bishir, Catherine (2005). North Carolina Architecture. UNC Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780807856246.

- Lewis, J.D. "Chatham Courthouse". The American Revolution in North Carolina. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- Patrick J. Huber, "Caught Up in the Violent Whirlwind of Lynching": The 1885 Quadruple Lynching in Chatham County, North Carolina, The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 75, No. 2 (APRIL 1998), pp. 135–160; via JSTOR. Retrieved 09 June 2018

- "George Moses Horton, 1798?-ca.1880". Docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- Hudson, Marjorie (February 22, 1999). "The George Moses Horton Project: Celebrating a triumph of literacy". Learnnc.org. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "George Moses Horton Project". Chathamarts.org. November 18, 2000. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "Chatham County: Interesting Facts & Tidbits". Chathamnc.org. July 31, 2007. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- Rockingham Post-Dispatch, September 22, 1921, p. 2.

- Hickory Daily Record, September 19, 1921, p. 2.

- Bruce E. Baker, "Lynching", 2006, Encyclopedia of North Carolina, ed. by William S. Powell. Retrieved 09 June 2018

- Sarah Burke, "Without Due Process: Lynching in North Carolina 1880–1900", Explorations, n.d., University of North Carolina Wilmington. Retrieved 09 June 2018

- Lynching in America Archived 2017-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, 3rd edition, Supplement: Lynching by County, p. 7, Montgomery, Alabama: Equal Justice Initiative, 2017

- "Carolina Coal Company Mine Explosion, Coal Glen, North Carolina". May 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- Reinemund, John A. (1955). "Geology of the Deep River Coal Field North Carolina" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. p. 18. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- "NC Mineral Resources - An Overview". North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- "2020 County Gazetteer Files – North Carolina". United States Census Bureau. August 23, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- Archived August 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Paleobiology Database". Paleodb.org. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "Chatham County - County Parks & Trails". Chatham Co. NC, USA. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- "Jordan Lake State Recreation Area". ncparks.gov. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- "NCWRC Game Lands". www.ncpaws.org. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- Alexandre, Tanzi (October 6, 2018). "Stark Differences in U.S. Life Expectancy: Demographic Trends". Bloomberg.

- "Chatham County census tract deemed area with nation's best life expectancy". Chatham News + Record. December 8, 2018.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Commissioner Contacts & Bios". chathamnc.org. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- "Public Officials Directory 2021 Federal, State, County". Chatham County Board of Elections. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- Debra Henzey. "County Government 101: The Fundamentals of Chatham County Government". Chatham Co. NC, USA. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- "Home – Woods Charter School". woodscharter.org. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Chatham County : Transportation in or Near Chatham County". Chathamnc.org. December 21, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "Family Fun Activities To Do Near Me in Chatham County, North Carolina". Chatham County Events. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Chatham Journal". chathamjournal.com. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Chatham News & Record | award winning news in Chatham County". thechathamnews.com. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Chatham News & Record | award winning news in Chatham County". thechathamrecord.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Chatham County Line – Where all voices are heard – Your community newspaper serving all of Chatham County and southern Orange County, NC since 1999". chathamcountyline.org. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans in Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, 1995–2005

- "UNC-TV ONLINE: Black Issues Forum:Transcripts". Unctv.org. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- Macky Alston (September 15, 1998). "Family Name | POV". PBS. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

Works cited

- "Negro Is Lynched By Mob Near Pittsboro". Hickory Daily Record. Hickory, Catawba, North Carolina: Samuel Howard Farabee and Jacob Carlyle Miller. 2021. p. 6. ISSN 1061-5628. OCLC 13340814. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- The New York Times (October 5, 1919). "For Action on Race Riot Peril". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- "Lynching at Pittsboro". Rockingham Post-Dispatch. Rockingham, Richmond, North Carolina: Isaac Spencer London. 2021. p. 12. ISSN 2376-0168. OCLC 24789326. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

Further reading

- Larry C. Thomas, The Double Axe Murder of the Gunter's and Finch's Family of Chatham County, North Carolina, Sanford, NC: The Author, 1990