Cherusci

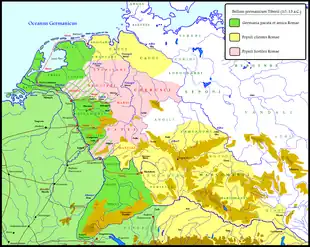

The Cherusci were a Germanic tribe that inhabited parts of the plains and forests of northwestern Germany in the area of the Weser River and present-day Hanover during the first centuries BC and AD. Roman sources reported they considered themselves kin with other Irmino tribes and claimed common descent from an ancestor called Mannus. During the early Roman Empire under Augustus, the Cherusci first served as allies of Rome and sent sons of their chieftains to receive Roman education and serve in the Roman army as auxiliaries. The Cherusci leader Arminius led a confederation of tribes in the ambush that destroyed three Roman legions in the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9. He was subsequently kept from further damaging Rome by disputes with the Marcomanni and reprisal attacks led by Germanicus. After rebel Cherusci killed Arminius in AD 21, infighting among the royal family led to the highly Romanized line of his brother Flavus coming to power. Following their defeat by the Chatti around AD 88, the Cherusci do not appear in further accounts of the German tribes, apparently being absorbed into the late classical groups such as the Saxons, Thuringians, Franks, Bavarians, and Allemanni.

Name

Cherusci (Latin: [kʰeːˈrus.kiː]) is the Latin name for the tribe. Both it and the Greek form Khēroûskoi (Χηροῦσκοι) are presumably transcriptions of an otherwise unattested Old Germanic demonym, whose etymology is unclear. The dominant opinion in scholarship is that it may derive from *herut ("hart"), which may have had totemistic significance for the group.[1] Another hypothesis—proposed in the 19th century by Jacob Grimm and others—derives the name from *heru- (Gothic: hairus; heoru, a kind of sword).[2] Hans Kuhn has argued that the derivational suffix -sk- involved in both explanations is uncommon in Germanic. He suggested that the name may therefore be a compound of ultimately non-Germanic origin and connected to the hypothesized Nordwestblock.[3]

History

The Cherusci were a Germanic tribe living around the central Weser River in the 1st century BC and 1st century AD.[5] They are first attested in Julius Caesar's Commentaries on the Gallic War. Caesar relates that in the year 53 BC he crossed the Rhine to punish the Suebi for sending reinforcements to the Treveri. In passing, he mentions that the Suebi were separated from the Cherusci by the "Bacenis Forest", a relatively impenetrable beech forest, possibly the Harz.[6] Pliny grouped them with the nearby Suebi, Chatti, and Hermunduri as Irminones, tribes who claimed descent from an ancestor named Mannus.[7] Tacitus later placed them between the Chatti and the Chauci, generally taken to indicate a territory between the Weser and Elbe.[8]

As part of his German campaigns, Drusus marched an army east into the territory of the Cherusci in 11 BC and was ambushed as he returned west at a narrow pass called Arbalo, probably near modern Hameln or Hildesheim. The Cherusci were initially victorious but paused their attack, allowing the surviving Romans to break through the encirclement and escape.[9] By that winter, Drusus had recovered enough control that a garrison was stationed somewhere in Cheruscan territory, probably at either Haltern or Bergkamen in North Rhine-Westphalia.[9] The Cherusci continued to resist the campaigns of Tiberius, L. Domitius Ahenobarbus, and M. Vinicius as late as the "vast war"[10] begun around 2 BC.

Finally, in AD 4, Tiberius overcame the factions of the Cherusci still hostile to Rome and by the next year he considered the tribe a Roman ally, giving it special privileges. The chieftain Segimer sent at least two sons who became Roman citizens and served in the Roman military as cavalry auxiliaries. The elder son Arminius returned as an auxiliary commander under P. Quictilius Varus, who began organizing Germany as the new province of Germania Magna in AD 7. This involved expanded taxation and demands of tribute, and Arminius began organizing a combined attack on Varus's legions. A Cheruscan noble named Segestes attempted to warn the governor repeatedly, but Varus ignored him and followed Arminius into an ambush in the Teutoburg Forest and marshes in AD 9. Working together, the Cherusci, Bructeri, Marsi, Sicambri, Chauci, and Chatti completely destroyed the 17th, 18th, and 19th Legions; Varus and many of the officers fell on their swords during the battle.[11][12] Cassius Dio reports that Segimer was second in command during the battle but Arminius seems to have acted as chieftain himself soon thereafter. He abducted Segestes's daughter Thusnelda and married her.

The Romans encouraged the Marcomanni to attack the Cherusci and launched punitive raids of their own, eventually recovering some of the lost eagle standards from the defeated legions. In AD 14, Germanicus raided the Chatti and Marsi with 12,000 legionnaires, 26 cohorts of auxiliaries, and eight cavalry squadrons and systematically laid waste to an area 50 miles wide such that "no sex, no age found pity".[13] He then campaigned against the Cherusci,[14] freeing Segestes from captivity and seizing the pregnant Thusnelda.[15][16] Arminius assembled the Cherusci and surrounding tribes while Germanicus marched some men east from the Rhine and sailed others from the North Sea up the Ems, attacking the Bructeri on their way.[17] These two forces met and then ravaged the land between the Ems and the Lippe. When they reached the Teutoburg Forest, they found the bodies of the slain Romans unburied and in places sacrificed on German altars. The army buried the dead for half a day, after which Germanicus stopped the work to return to war against the Germans.[18] Making his way to the Cherusci heartland, Germanicus was attacked by Arminius's men at Pontes Longi ("the long causeways") in the boggy lowlands near the Ems. The Cherusci trapped and began to kill the Roman cavalry but the Roman infantry was able to check and rout them over the course of a two day battle. Tacitus considered this a victory[19] although historians such as Wells think it was more likely inconclusive.[20]

In AD 16, Germanicus returned with eight legions and Gallic and Germanic auxiliary units, including men led by Arminius's younger brother Flavus. Marching from the Rhine and along the Ems and Weser, the Romans met Arminius's forces at the plains of Idistaviso by the Weser near modern Rinteln. Tacitus reports the Battle of the Weser River as a decisive Roman victory:[21][22]

The enemy were slaughtered from the fifth hour of daylight to nightfall, and for ten miles the ground was littered with corpses and weapons.

Arminius and his uncle Inguiomer were both wounded but evaded capture. The Roman soldiers proclaimed Tiberius as imperator and raised a pile of arms as a trophy with the names of the defeated tribes inscribed beneath them.[23][24] This trophy enraged the Germans, who ceased retreating beyond the Elbe and regrouped to attack the Romans at the Angrivarian Wall. This battle also ended in a decisive Roman victory, with Germanicus supposedly directing his men to exterminate the Germanic tribes. A mound was raised with an inscription reading "The army of Tiberius Caesar, after thoroughly conquering the tribes between the Rhine and the Elbe, has dedicated this monument to Mars, Jupiter, and Augustus."[25][26] In the next year, Germanicus was recalled to Rome. Tacitus reports this as partially caused by the emperor's growing jealousy of the general's fame, but permitted him to celebrate a triumphal march on 26 May:

Germanicus Caesar, celebrated his triumph over the Cherusci, Chatti, and Angrivarii, and the other tribes which extend as far as the Elbe.[27]

Germanicus was then moved to the Parthian border in Syria and soon died, possibly from poisoning. Arminius was killed in turn by Segestes and his allies in AD 21.

After Arminius's murder, the Romans left the Cherusci more or less to their own devices. In AD 47, the Cherusci asked Rome to send Italicus, the son of Flavus and nephew of Arminius, to become their chieftain, as civil war had destroyed their other nobility. He was initially well liked but, since he was raised in Rome as a Roman citizen, he soon fell out of favor.[28] He was succeeded by Chariomerus, presumably his son, who was defeated by the Chatti and deposed around AD 88.[29]

Tacitus (56–c. 120) writes of the Cherusci:

Dwelling on one side of the Chauci and Chatti, the Cherusci long cherished, unassailed, an excessive and enervating love of peace. This was more pleasant than safe, for to be peaceful is self-deception among lawless and powerful neighbours. Where the strong hand decides, moderation and justice are terms applied only to the more powerful; and so the Cherusci, ever reputed good and just, are now called cowards and fools, while in the case of the victorious Chatti success has been identified with prudence. The downfall of the Cherusci brought with it also that of the Fosi, a neighbouring tribe, which shared equally in their disasters, though they had been inferior to them in prosperous days.[30]

Claudius Ptolemy's Geography places the Cherusci, Calucones, and Chamavi (Καμαυοὶ, Kamauoì) all near one other and "Mount Melibocus" (probably the Harz Mountains).[31]

The later history of the Cherusci is unattested.

See also

- List of Germanic peoples

- Barbarians, a 2020 TV series dramatizing the events around the Battle of Teutoburg Forest

Notes

References

Citations

- Reallexikon der Germanischen Alterturmskunde. Vol. 4. 1981. p. 430 ff., s.v. "Cherusker"; cf. also Rudolf Much; Herbert Jankuhn; Wolfgang Lange (1967). Die Germania des Tacitus. Heidelberg: Winter. p. 411.

- Jacob Grimm (1853). Geschichte der Deutschen Sprache. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Leipzig. p. 426.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Reallexikon der Germanischen Alterturmskunde. Vol. 1. 1973. pp. 420–421, s.v. "Arminius".

- Beard 2007, p. 108.

- Thompson, Edward Arthur; et al. (2012), "Cherusci", The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780191735257,

Cherusci, a Germanic people, living around the middle Weser. They are the best known of the Germanic opponents of the Romans in the 1st cent. AD.

- Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic War, 6.10.

- Pliny, Nat. Hist., 4.28.

- Smith, William (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

- Powell, Lindsay (2013), Eager for Glory: The Untold Story of Drusus the Elder, Conqueror of Germania, Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books, Chapter 5, ISBN 978-1-78303-003-3, OCLC 835973451.

- Velleius Paterculus, Rom. Hist.

- Roberts 1996, pp. 65–66.

- Ozment 2005, pp. 20–21.

- Tacitus, Ann., 1, 51.

- The Works of Tacitus, Vol. 1: The Annals, London: Bohn, 1854, Book 1, Ch. 60, & Book 2, Ch. 25.

- Wells 2003, p. 204-205.

- Seager 2008, p. 63.

- Wells 2003, pp. 204–205.

- Wells 2003, pp. 196–197.

- Tacitus & Barrett 2008, p. 39

- Wells 2003, p. 206

- Wells 2003, p. 206.

- Tacitus & Barrett 2008, p. 57.

- Tacitus & Barrett 2008, p. 58.

- Seager 2008, p. 70.

- Tacitus & Barrett 2008, pp. 58–60.

- Dyck 2015, p. 154.

- Tacitus, Annals, 2.41

- Tacitus, Annals, 11.16.

- Cassius Dio, Epitome, 67, 5.

- "Tac. Ger. 36". Perseus Project. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- Ptolemy, Geogr. 2, 11, 10.

Bibliography

- Beard, Mary (2007), The Roman Triumph, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02613-1

- Dyck, Ludwig Heinrich (2015), The Roman Barbarian Wars: The Era of Roman Conquest, Pen and Sword, ISBN 9781473877887

- Seager, Robin (2008), Tiberius, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9780470775417

- Tacitus, Cornelius (2008), Barrett, Anthony (ed.), The Annals: The Reigns of Tiberius, Claudius, and Nero, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780192824219

Further reading

- Tacitus, Cornelius and Michael Grant, The Annals of Imperial Rome. New York: Penguin Books, 1989.

- Caesar, Julius et al. The Battle for Gaul. Boston: D. R. Godine, 1980.

- Wilhelm Zimmermann, A Popular History of Germany (New York, 1878) Vol. I

- Ptolemy, "Geography"

- Max Ihm, Cherusci. In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (RE). volume III,2, Stuttgart 1899, Sp. 2270–2272.

- Ralf Günther Jahn, Der Römisch-Germanische Krieg (9–16 n. Chr.). Diss., Bonn 2001.

- Peter Kehne, Zur Lokalisierung, Organisation und Geschichte des Cheruskerstammes. In: Michael Zelle (Hrsg.), Terra incognita? Die nördlichen Mittelgebirge im Spannungsfeld römischer und germanischer Politik um Christi Geburt. Akten des Kolloquiums im Lippischen Landesmuseum Detmold vom 17. bis 19. Juni 2004. Philipp von Zabern Verlag, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-3632-1, pages 9–29.

- Gerhard Neumann, Reinhard Wenskus, Rafael von Uslar, Cherusker. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2. Auflage. volume 4, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin – New York 1981, pages 430–435.

- Ozment, Steven (2005). A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06093-483-5.

- Roberts, J. M. (1996). A History of Europe. New York: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-96584-319-5.

- Oberst Streccius, Cherusker. In: Bernhard von Poten (Hrsg.): Handwörterbuch der gesamten Militärwissenschaften. volume 2, Bielefeld/Leipzig 1877, page 235.

- Wells, Peter S. (2003). The Battle That Stopped Rome. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32643-7.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 89.