Chicago railroad strike of 1877

The Chicago railroad strike of 1877 was a series of work stoppages and civil unrest in Chicago, Illinois, which occurred as part of the larger national strikes and rioting of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Meetings of working men in Chicago on July 26 led to workers from a number of industries striking on the following morning, and over the next few days, large crowds gathered throughout the city, resulting in violent clashes with police. By the time order was restored on the evening of July 26, 14 to 30 rioters were dead or dying, and 35 to 100 civilian and nine to 13 policemen were wounded.

| Chicago railroad strike of 1877 | |

|---|---|

| Part of Great Railroad Strike of 1877 | |

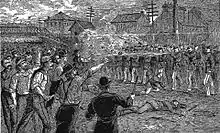

.png.webp) Violence in Chicago as depicted on the August 11, 1877 cover of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper | |

| Location | |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 14-30 |

| Injuries | 44-113[1]: 391 [2] |

The Long Depression and the Great Strikes

| 1850s–1873 | 1873–1890 | 1890–1913 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.3 | 2.9 | 4.1 | |

| 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | |

| 6.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | |

| 1.7 | 1.3 | 2.5 | |

| 0.9 | 3.0 | ||

| 3.1 | 3.5 |

The Long Depression, sparked in the United States by the Panic of 1873, had far-reaching implications for US industry, closing more than a hundred railroads in the first year and cutting construction of new rail lines from 7,500 miles (12,100 km) of track in 1872 to 1,600 miles (2,600 km) in 1875.[4] Approximately 18,000 businesses failed between 1873 and 1875, production in iron and steel dropped as much as 45 percent, and a million or more lost their jobs.[5][6] In 1876, 76 railroad companies went bankrupt or entered receivership in the US alone, and the economic impacts rippled throughout many economic sectors throughout the industrialized world.[7]: 31

During the summer of 1877, tensions erupted across the nation in what would become known as the Great Railroad Strike or simply the Great Strikes. Work stoppage was followed by civil unrest across the nation. Violence began in Martinsburg, West Virginia and spread along the rail lines through Baltimore and on to several major cities and transportation hubs of the time, including Reading, Scranton and Shamokin, Pennsylvania; and a bloodless general strike in St. Louis, Missouri. In the worst case, rioting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania left 61 dead and 124 injured. Much of the city's center was burned, including more than a thousand rail cars destroyed. What began as the peaceful actions of organized labor attracted the masses of working discontent and unemployed of the depression, along with others who took opportunistic advantage of the chaos. In total, an estimated 100,000 workers participated nationwide.[8] State and federal troops followed the unrest as it spread along the rail lines from city to city, beginning in Baltimore, where the movement of troops itself provoked a violent response that eventually required federal intervention to quell.[9][1]

Chicago

By the time unrest reached Chicago, reports had widely circulated of burning, looting, and violence in major cities including Baltimore and Pittsburgh.[9]: 27 : 310 This served to grow tensions, as newspapers reported the march of unrest westward, but it also afforded officials to the opportunity to prepare, a luxury other cities had not enjoyed, as they had been forced to hastily swear in police and muster militia after violence was well underway.[9]: 308–11 [lower-alpha 1]

In Chicago there existed a substantial organized communist movement, who viewed the strikes approaching from the east as an opportunity to further their cause. On July 22 they released a statement:

In the desperate struggle for existence now being maintained by the workingmen of the great railroads throughout the land, we expect that every member will render all possible moral and substantial assistance to our brethren, and support all reasonable measures which may be found necessary by them.[1]: 370

They sought two main goals: the nationalization of the rail and telegraph lines by the federal government, and the institution of an eight-hour workday, which they believed would provide room for more of the unemployed to enter the workforce.[1]: 370

Throughout the day meetings were held by the men of the Michigan Southern, Rock Island, Chicago & North Western, and the Milwaukee & St. Paul railroads. Although they were secret meetings, and no record was kept of their goings on, a letter from Chicago characterized the effect of the workers: "One thing has been apparent all day. Where the men were silent yesterday, they freely discuss the practicability of a strike today."[1]: 371–2 The decision was made to suspend movement on the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago line until the excitement had passed.

July 23

City authorities prepared for potential unrest in earnest, deploying muskets to police stations and equipping a newly created artillery company with three cannons. The governor ordered local militia to the ready to assist civil authorities if called upon to do so.[1]: 372 There were multiple confrontations between crowds and police, forcing the police to retire.[9]: 316

That night a meeting of as many as 10,000 occurred on Market Street. Speakers impressed on the crowd the need to join the strikes taking place elsewhere. They carried banners reading "We want work, not charity" and Life by work, or death by fight". As one speaker put it, "We must rise up in our might, and fight for our rights. Better a thousand of us be shot down in the streets than ten thousand die of starvation."[1]: 373

The crowd retired by 11:30 PM, but resolved to meet again at 10:00 AM the following morning.[1]: 373

July 24

The next morning a committee of workers met with officer of the Michigan Central Railroad, and demanded a restoration of recent wage cuts. The company refused, and the work was swiftly stopped.[1]: 373 At 9:00 AM 165 workers of the Illinois Central Railroad joined those of the Michigan Central and quietly stopped work. A combined group of 500 then began a procession through the various rail yards. They made their way through the Baltimore & Ohio, Rock Island, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy and Chicago & Alton, and as they went the strike spread with them.[1]: 375–6 By noon only a single railroad, the Chicago and North Western, had any traffic in or out of the city, but it too would be forced to close by the end of the day.[9]: 311–3

Others, a crowd of 500 not affiliated with the railroads, marched through the streets of the lumber yards and planing mills, demanding that those there quit work, which many did.[1]: 377–8 This continued until all types of industry was idle throughout the city, some for the striking of the men, and others shuttered by their owners for fear of the crowd.[1]: 377–8

The militia began to prepare for confrontation, and new police were sworn in in anticipation of events. Mayor Heath released a proclamation. Fearing that some may "seize this as a favorable opportunity to destroy property and commit plunder", he called upon:

on all good citizens to aid in enforcing the laws and ordinances, and in suppressing riot and other disordely conduct. To this end I request that the citizens organize patrols in their respective eneighborhoods, and keep their women and children off the public highways.[1]: 379

He then ordered all barrooms and saloons closed effective 6:00 PM that day.[1]: 380 Small skirmishes broke out between police and the bands of strikers throughout the city, but no one was seriously injured.[1]: 381 Some stopped cars on Blue Island Avenue, and their leaders were rounded up and arrested.[9]: 314

July 25

On the morning of Wednesday the 25th it was announced that the Union Stock Rolling Mills and the Malleable Iron works had both closed.[9]: 315 Crowds gathered and forced the Phoenix Distillery to do the same.[9]: 316

The mayor issued a recommendation that citizens organize themselves into safety guards for their neighborhoods.[1]: 381 Meetings of local businessmen and merchants were held, and the city counsel voted to give the mayor plenary powers.[1]: 381

Crowds of 25,000 and 40,000 gathered at the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy roundhouse and extinguished the fires in the engines there.[1]: 382 When police arrived they were assailed by stones. They fired into the crowd over ten minutes, killing three, and wounding 16.[1]: 382 The crowd retreated up Halstead street and attacked streetcars in the viaduct there. On South Halstead Street some broke into a gun shop and looted 200 shotguns and revolvers.[1]: 382

July 26

Additional regulars arrived from the west on Thursday July 26, bringing the total number of federal troops in the city to 12 companies.[1]: 383 Orders came down from President Rutherford B. Hayes placing these in under the command of the governor.

At 9:00 AM a crowd gathered at Turner Hall, on West Twelfth Street for a meeting held there, and soon began to grow into an unruly mob. At 10:00 AM a group of 25 police arrived and were assailed by stones and other missiles.[1]: 385 Another group of 20 officers joined and a fight ensued, first on the street, and then in the hall when the police forced their way into it. One police officer was injured.[1]: 385–6

Battle of the Viaduct

Elsewhere at the Halstead Street viaduct, the mob stopped streetcars and threw stones and fired pistols at the group of 25 police who arrived at the scene.[1]: 386–7 The police returned fire, eventually exhausted their ammunition, and were forced to retreat.

By 11:00 AM the crowd there had grown to 10,000.[2] They were met with a larger detachment of police who charged the crowd with baton and pistol. The crowd broke and fled to the opposite site of the viaduct and into adjacent streets. Firing continued for a half hour, until, low on ammunition, the police once again were forced to withdraw. This initially orderly retreat turned into a rout, and they fled as far as Fifteenth Street where they met with a cavalry unit and police reinforcements.[1]: 388–9

The combined force charged the mob, who broke and ran. They fired at the crowd and killed at least two. Others were beaten, at least one badly, having his skull crushed. The cavalry remained in the area the rest of the day to disperse groups as they gathered, and detain those who would not be removed. In this way more than a hundred were arrested.[1]: 389 They were later reinforced by the Second Illinois Regiment, along with two artillery pieces, and at 12:30, at the mayor's behest, two additional companies of regular were dispatched.[1]: 390

Order restored

Additional troops throughout the day arrived and were stationed throughout the city, where they continually dispersed groups, and prevented any large crowds from forming. Due to their success, no other large outbreaks took place that day. When all was finished, 14 to 30 rioters were dead or dying, and 35 to 100 were wounded, as well as nine to 13 policemen.[1]: 391 [2]

Resolution and aftermath

On the morning of Friday July 27, five companies were dispatched to disperse crowds gathered at the corner of Archer Avenue and South Halstead Street, where they were joined by 300 additional cavalry and infantry.[1]: 391

Mayor Heath issued a proclamation:

The city authorities, having dispersed all lawlessness in the city, and law and order being restored, I now urge and request all business men and employers generally to resume work, and give as much employment to their workmen as possible.[1]: 392 [lower-alpha 2]

From that point onward the city was quiet. The railroad workers, returned to work at their previous wages, demoralized by the failure of similar strikes throughout the country.[1]: 392–3

See also

Notes

- On July 22, Baltimore set about swearing in 2,000 additional militia after three days of violence.[10] Similarly, on July 23, Pittsburgh set about organizing several thousand under General James S. Negley after two days of violence and fire had destroyed or damaged substantial portions of the city.[1]: 113–4

- The full proclamation read: The city authorities, having dispersed all lawlessness in the city, and law and order being restored, I now urge and request all business men and employers generally to resume work, and give as much employment to their workmen as possible. I consider this the first duty of our business community. I am now amply able to protect them and their workmen. Let everyone resume operations and report any interference at police headquarters. Citizens' organizations must continue in force, and on no account relax their vigilance, as the cause of trouble is not local and not yet removed. All such organizations should form themselves into permanent bodies, continue on duty and report regularly as heretofore.[1]: 392

References

- McCabe, James Dabney; Edward Winslow Martin (1877). The History of the Great Riots: The Strikes and Riots on the Various Railroads of the United States and in the Mining Regions Together with a Full History of the Molly Maguires. National Publishing Company.

- "The Battle of the Halsted Viaduct". UChicago Events. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Andrew Tylecote (1993). The long wave in the world economy. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-415-03690-0.

- Kleppner, Paul (1973). "The Greenback and Prohibition Parties". In Schlesinger, Arthur M. (ed.). History of U.S. Political Parties: Volume II, 1860-1910. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. p. 1556. ISBN 9780835205948.

- David Glasner, Thomas F. Cooley (1997). "Depression of 1873–1879". Business Cycles and Depressions: An Encyclopedia. New York & London: Garland Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-0-8240-0944-1.

- Philip Mark Katz (1998). Appomattox to Montmartre: Americans and the Paris Commune. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-674-32348-3.

- Laurie, Clayton (July 15, 1997). The role of federal military forces in domestic disorders, 1877-1945. Government Printing Office.

- Kunkle, Fredrick (September 4, 2017). "Labor Day's violent roots: How a worker revolt on the B&O Railroad left 100 people dead". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- Dacus, Joseph (1877). Annals of the Great Strikes in the United States: A Reliable History and Graphic Description of the Causes and Thrilling Events of the Labor Strikes and Riots of 1877. L.T. Palmer.

- "The revolt on the railroads" (PDF). The Sun. July 24, 1877. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

.jpg.webp)