San Francisco riot of 1877

The San Francisco riot of 1877 was a three-day pogrom waged against Chinese immigrants in San Francisco, California by the city's majority white population from the evening of July 23 through the night of July 25, 1877. The ethnic violence which swept Chinatown resulted in four deaths and the destruction of more than $100,000 worth of property belonging to the city's Chinese immigrant population.

| 1877 San Francisco riots | |

|---|---|

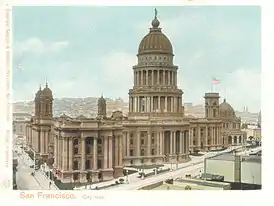

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Illustration by H.A. Rodgers for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (March 20, 1880) showing a Workingmen's Party of California anti-Chinese rally on the sand lots near San Francisco City Hall | |

| Location | San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Date | July 23, 1877—July 25, 1877 |

Attack type | Riot, pogrom |

| Deaths | 4 |

| Injured | Unknown |

| Victims | Chinese community of San Francisco |

| Perpetrators | White mobs |

| Motive | Sinophobia |

Background

Historian Theodore Hittell wrote about the developing competition between Chinese and European workers, initially in mining and then in more general work throughout the 1850s: "As a class [the Chinese] were harmless, peaceful and exceedingly industrious; but, as they were remarkably economical and spent little or none of their earnings except for the necessaries of life and this chiefly to merchants of their own nationality, they soon began to provoke the prejudice and ill-will of those who could not see any value in their labor to the country. ... By degrees they began also to branch out into occupations which interfered or were supposed to interfere with the wages of white labor. They not only hired out as servants and laborers; but they became laundrymen and turned their attention successfully to various mechanical branches of industry, which would yield them wages, and in a number of ways picked up money, which would have otherwise gone into white hands."[1]: 99–100 Many of the Chinese immigrants who had come to the U.S. to work on the First transcontinental railroad were left looking for other employment after its completion in 1869; in San Francisco, Chinese workers were often hired at cheaper rates than European workers, and the Chinese immigrants were often convenient scapegoats for larger economic inequalities.[2][3]

From 1873 through the rest of the 1870s a severe economic crisis swept the United States of America known to history as the Long Depression. Economic contraction in the eastern United States proved the motivation for many to pull up stakes and try to re-establish themselves in the West Coast. Indeed, between the years 1873 and 1875 an estimated 150,000 workers made their way to the "Golden State", many of whom settled in the state's only metropolis, San Francisco.[4]: 253 By that time, San Francisco had already experienced two cycles of boom and bust: first in the 1850s, as the Gold Rush dried up, and then in the 1870s, after the Comstock Lode had been mined.[2]

By 1877 the depression that had already long plagued the East Coast arrived on the West Coast as well, and San Francisco's unemployment rate skyrocketed[4]: 253 to approximately 20% of adult men, coinciding with a downturn in mining stocks.[2] There was no city or state central labor authority, no government provision for unemployed workers, and discontent was rampant.[4]: 253 [5]: 88 In San Francisco, with approximately 200,000 residents, the Chinese made up approximately 10% of the population; white and Chinese competed for the same jobs, with Chinese labor being decidedly cheaper.[2]

The sand lot rally

On July 23, 1877, the Daily Alta California, which had been covering the Pittsburgh railroad strike of 1877, ran an article describing the clashes between striking workers and soldiers.[6] That afternoon, a meeting scheduled for 7:30 p.m. was organized by the fledgling Workingmen's Party of the United States to agitate on behalf of the needs of the labor movement and those of unemployed workers in particular.[4]: 253 [7] City authorities granted permission for the gathering, which was to be held on vacant lots adjoining San Francisco City Hall,[4]: 253 which was then under construction; the site is now occupied by the main branch of the San Francisco Public Library.[8]

As the day of the scheduled mass meeting arrived, rumors were rampant in the city, including one that arson was being planned to destroy the docks of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company – the chief mode of transport of immigrant workers from China to the USA – as well as an attack on the city's Chinese quarter.[4]: 253 [5]: 89 On the afternoon of July 23, San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) chief Henry H. Ellis had written to Brigadier General John McComb, requesting the California state militia be mobilized and held in readiness to suppress a potential riot.[9][10] The leaders of the Workingmen's Party promised "no threats of violence or incendiary language" would be tolerated at the rally, mollifying city officials and political leaders, who did not attempt to intervene, and the July 23 meeting proceeded as scheduled.[4]: 253 [5]: 89

Nearly 8,000 people turned up for the socialist meeting at the so-called "sand-lots" in front of City Hall.[4]: 253 It was characterized as "quiet, orderly, and good natured", marred only by a drunken man shooting wildly into the crowd without provocation.[5]: 89 [11] Several representatives of the Workingmen's Party addressed the throng on the labor question, but none of them so much as mentioned the city's Chinese population, let alone attempted to lay blame upon them as the cause of the unemployment problem;[4]: 253 The first speaker, Chairman James D'Arcy, explicitly stated this was not an "anti-Coolie meeting" and was meant to be a rally to support the workingmen of Pittsburgh, but was repeatedly interrupted by the crowd's shouts: "Talk about the Chinamen" and "Give us the Coolie business". Successive speakers were shouted down as well.[7]

The Daily Alta article stated that a Dr. O'Donnell was permitted to speak on the condition that "he not slop over on his Anti Coolie hobby" and his speech was interrupted several times, first by Chairman D'Arcy to solicit donations to cover the cost of the band, then by the arrival of the Anti Coolie club from Platt's Hall, and finally by "[a] gang of some two hundred young hoodlums" who rushed from the McAllister side of the rally site up Leavenworth, "hooting and yelling in a fearful manner." As O'Donnell was concluding his speech, the gasoline-powered light failed and a fire alarm was sounded, dispersing the crowd. The Daily Alta summed up the rally as "simply a fizzle. The crowd was a good-natured one, the speakers very poor, and the result, as far as aiding their brethren goes, nil."[7]

The riots

Riots broke out the night of July 23 in the wake of the sandlot rally, and continued over the next two nights. The ethnic violence was only halted through the combined efforts of the SFPD, the California state militia, and as many as 1,000 members of the civilian group "Committee of Safety", each armed with a hickory pickaxe handle.[4]: 253–254 The multi-day riot collectively claimed four lives and inflicted more than $100,000 worth of property damage upon the city's Chinese immigrant population.[4]: 253 In total, twenty Chinese-owned laundries were destroyed in the violence and San Francisco's Chinese Methodist Mission suffered smashed glass when the mob pelted it with rocks.[12]

July 23, 1877

The gang of hoodlums that rushed up Leavenworth at the conclusion of the first sandlot rally was blamed for starting the first riot on the night of July 23,[9] at approximately 9 p.m.[5]: 90 Historian Selig Perlman recounts the origin of the riot, sparked at the end of the rally:

"Everything was orderly until an anti-coolie procession pushed its way into the audience and insisted that the speakers say something about the Chinese. This was refused and thereupon the crowd which had gathered on the outskirts of the meeting attacked a passing Chinaman and started the cry, 'On to Chinatown.'"[4]: 253

The precipitating event may have been the arrest of one of the hoodlums (for knocking down a Chinese passer-by) and the hoodlum's subsequent rescue from the police.[5]: 90 One of the first businesses to be destroyed was a Chinese-owned laundry in the basement of a two-story building at Leavenworth and Geary; the rioters beat the Chinese occupants and set the business on fire with oil lamps. Civilians living in the upper stories required rescue, and the rioters continued to bedevil San Francisco Fire Department (SFFD) personnel by cutting their hoses in several places.[9] The rioters continued down Geary, stopping to destroy several more laundries and the windows of the Gibson Chinese Mission (at 916 Washington) before turning towards Chinatown; the Daily Alta said there was "no reasonable doubt that [Chinese laundry proprietors] would have been murdered had they remained."[9] The total cost of the damage during that night was estimated at US$20,000 (equivalent to $550,000 in 2022);[5]: 90 no serious injuries were reported among the Chinese immigrant population.[9]

_-_Local_Chips_(cropped).jpg.webp)

By this time, the police had been apprised of the mob's approach to Chinatown and took up two positions at California and Dupont (now Grant) and California and Stockton. The mob, now numbering in the thousands, marched down Sutter to Dupont and started north into Chinatown after ransacking another laundry, but were stopped by the police officers stationed at California and Dupont. The police drove the mob back to Stockton and California, where they were joined by the other group of officers, and the combined forces pushed the mob back to Market, quelling the first night's activity by 11 p.m.[9]

July 24, 1877

On July 24, General McComb called a meeting of prominent San Francisco citizens, business leaders, and politicians including Mayor Andrew Jackson Bryant, where they formed the Committee of Safety, led by an executive committee of twenty-four civilians chartered "to preserve the peace and well-being of the city, with our money and persons." W.T. Coleman was nominated for Chairman and unanimously elected. Their stated goal was to be able to mobilize 20,000 armed civilians within twenty minutes to support smaller numbers of police (250) and state militia (1,200) in quelling another riot.[13] Later estimates established that approximately 4,000 civilians who worked for the Committee of Safety were mustered and armed.[5]: 91 Several of them received special 24 hour deputy officer badges.[14]

Chinatown was perfectly motionless after nightfall. Not a soul stirred in that quarter except an occasional special officer, or mounted policeman clattering down the hills. The two theatres on Jackson street were not opened. The fact is that while the streets gave no signs of life, the walls simply shut out swarms of Chinamen, sleepless, armed and sullen. Not the slightest demonstration was made in that quarter. The severe rebuff administered to the incipient mob on Monday night on Dupont street had proved a wholesome lesson to the lawless elements.

— Daily Alta California, July 25, 1877.[15]

That night, riots broke out again in San Francisco, with gangs gathering and being dispersed by the police primarily south of Market;[15] One group of approximately 1,000 men gathered in front of the San Francisco Mint and marched down Mission, threatening to burn the Mission Woolen Mills for employing Chinese labor, but it was well-guarded[5]: 91 and four laundries on Mission (between Seventh and Twelfth) were sacked instead, as those businesses had been abandoned by their owners for the comparative safety of Chinatown.[15] Two laundries (one near Howard and Twelfth; the other at 1915 Hyde)[14] were looted and set on fire, and police disrupted another group of looters at Bryant and Twelfth, who were about to fire the laundry. There were no reports of violence within Chinatown itself.[15]

Across the Bay in Oakland, anti-Chinese activists held a rally, attracting a crowd of approximately 700 or 800.[16] The Mayor of Oakland met with prominent citizens to organize a similar Committee of Safety, based on violent threats issued at the rally.[17]

July 25, 1877

Two Chinese men were found dead in the ruins of a Chinese laundry in the Western Addition early in the morning of July 25th.[15] A coroner's inquest concluded that one of those killed, Wong Go, died from suffocation during the arson of the laundry. According to the testimony of the survivors, a group of white men had surrounded the building and fired shots into it, driving them out; the survivors did not notice that Wong Go had not joined them outside until the morning. Shortly after taking over the building and stealing approximately $150, the men set the building on fire.[18]

_-_Beale_Street_Fire_of_July_25%252C_1877.jpg.webp)

The men of the Committee of Safety were issued "clubs of the latest police pattern" (baseball bats) on July 25 in addition to any weapons they had brought.[19] That day, rumors again spread that rioters would burn the Pacific Mail docks; the police and "pick-handle brigade" were sent to protect it, and the rioters set fire to a nearby lumberyard at the Beale Street Wharf instead that night. Losses were estimated at US$200,000 (equivalent to $5,500,000 in 2022).[5]: 92 [20] In the ensuing battle, four were killed and fourteen were wounded.[5]: 92

Also that night, an anti-Chinese meeting attended by approximately 600 was held at the San Francisco City Hall sand-lots; the night's speaker, identified as N.P. Brock was derided as "very much under the influence of liquor, and whose anti-Coolie sentiments, enunciated in very uneven terms, caused great laughter and more ribald jests."[21] Brock declared he would lead the crowd to Chinatown; the crowd of rioters again demolished several Chinese-owned laundries, but the police and the "White Clubs" pick-handle brigade were able to disperse the rioters at Kearny and Post before they reached Chinatown.[5]: 92 [22] In one incident, a group of approximately 100 members of the Committee of Safety, in the process of returning criminals from the Beale Street Wharf fire, charged an equal number of rioters near Lotta's Fountain after the rioters began throwing cobblestones at them. At the same time, a police squadron came down Montgomery onto Market, pinching the rioters in between; according to the Daily Alta, "many of them fell senseless to the street under the strong blow of an officer's 'billy', or a Committeeman's staff".[23] The Daily Alta concluded the next day that "there are more sore heads in San Francisco today than can get well in a week."[22]

Oakland and San Jose remained quiet,[24][25] and the United States Navy dispatched the gunboats USS Pensacola and Lackawanna to San Francisco from Vallejo as a precaution in response to a request from Mayor Bryant and Governor William Irwin.[26] The night of July 26–27 was peaceful in San Francisco compared to the preceding eventful nights; just one laundry was reported to have been demolished,[27] and several fires were set.[28][29]

Aftermath and legacy

The July 1877 San Francisco riot's suppression did not mark the end of anti-Chinese activity in the city, but rather the beginning. One of those who had served in the so-called "Pick-Handle Brigade" which had helped to quell the rioting, an Irish wagon-driver named Denis Kearney, was drawn into political activity by the July events.[4]: 254

Kearney first applied for membership in the Workingmen's Party (later known as the Socialist Labor Party of America), but was denied on the basis of his outspoken public views on what he considered the "laziness" and "shiftlessness" of the working class.[4]: 254 Stymied from membership in the existing opposition political party, Kearney started a new organization of his own, the Workingmen's Trade and Labor Union of San Francisco, which made use of the mobilizing slogan "The Chinamen Must Go!"[4]: 254 This organization changed its name in October 1877 to the Workingmen's Party of California, of which Kearney served as president.[4]: 255 The new party retained the anti-Chinese focus and slogans of the earlier organization.

Anti-Chinese sentiment spread throughout the United States, culminating in the effective termination of importation of Chinese workers through passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.

In media

- Anton Refregier painted #19: "The Sand Lot Riots of 1870" (also known as "Beating the Chinese"), one of the 27 murals in the Rincon Annex Post Office collectively entitled History of San Francisco, completed in 1948. This painting depicts Chinese immigrants, who were accused of stealing jobs, being beaten by Irish workers.[30][31]

- A fictional version of the riots was incorporated into the ninth episode of season 2 of the television drama Warrior, first broadcast in 2020.[32]

See also

- Chinese American history

- Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States

- Chinese Exclusion Act

- Anti-Chinese violence in Oregon

- Anti-Chinese violence in California

- Anti-Chinese violence in Washington

- Chinese massacre of 1871

- Golden Dragon massacre, 1977

- Rock Springs massacre, 1885

- Attack on Squak Valley Chinese laborers, 1885

- Tacoma riot of 1885

- Seattle riot of 1886

- Hells Canyon massacre, 1887

- Pacific Coast Race Riots of 1907

- Bellingham riots of 1907

- Torreón massacre, 1911 in Mexico

- 2021 Atlanta spa shootings

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

References

- Hittell, Theodore H. (1898). "III | Early State Administrations: Bigler". History of California. Vol. IV. San Francisco: N.J. Stone & Company. pp. 89–113.

- Brekke, Dan (February 11, 2015). "Boomtown, 1870s: Decade of Bonanza, Bust and Unbridled Racism". KQED. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Brekke, Dan (February 12, 2015). "Boomtown, 1870s: 'The Chinese Must Go!'". KQED. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Perlman, Selig (1921). "The Anti-Chinese Agitation in California". In Commons, John R. (ed.). History of Labour in the United States. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan. pp. 252–268.

- Cross, Ira (1935). "VII: 'The Chinese Must Go'". A History of the Labor Movement in California. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 88–129. ISBN 9780520026469. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- "The Great Strike. A Day of Terror at Pittsburg". Daily Alta California. July 23, 1877. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "Workingmen's Meeting". Daily Alta California. July 24, 1877. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Schwartzenberg, Susan (1998). "Old City Hall of SF". Found SF. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- "Lawlessness Rampant". Daily Alta California. July 24, 1877. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- McComb, John (1878). "Reports of Brigadier Generals: To Brigadier-General P. F. Walsh, Adjutant-General, California". Appendix to the Journals of the Senate and Assembly. Vol. 1. Sacramento, California: State of California. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "An Outrageous Case--Two Men Wantonly Shot". Daily Alta California. July 24, 1877. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- Carlsson, Chris (1995). "The Workingmen's Party and The Dennis Kearney Agitation: Historical Essay". Found SF.

- "Committee of Safety". Daily Alta California. July 25, 1877. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "Police Arrangements". Daily Alta California. July 25, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "More Hoodlumism". Daily Alta California. July 25, 1877. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "Agitators at work in Oakland". Daily Alta California. July 25, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Oakland Aroused". Daily Alta California. July 25, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Coroner's Intelligence". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "Committee of Safety". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "The Beale Street Wharf Fire". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- "More Lawlessness". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- "Activity of the Committee of Safety". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "A Brave Charge". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Prompt Action in Oakland". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "San Jose All Right". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Government Aid". Daily Alta California. July 26, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Law and Order". Daily Alta California. July 27, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Incendiarism in the Mission". Daily Alta California. July 27, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Incendiary Fire at Mission Bay". Daily Alta California. July 27, 1877. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "National Register Information System – Rincon Annex (#79000537)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Highsmith, Carol M. (2012). "History of San Francisco mural "Beating the Chinese" by Anton Refregier at Rincon Annex Post Office located near the Embarcadero at 101 Spear Street, San Francisco, California". Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Ching, Gene (November 28, 2020). "Warrior: The Real History of the Race Riot that Shook San Francisco". Den of Geek. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

Further reading

- Jerome A. Hart, In Our Second Century: From an Editor's Notebook. San Francisco: Pioneer Press, 1931.

- Neil Larry Shumsky, The Evolution of Political Protest and the Workingmen's Party of California. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1992.

- Darren A. Raspa, Bloody Bay: Grassroots Policing in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020.

External links

- Chris Carlsson, "The Workingmen's Party and The Dennis Kearney Agitation: Historical Essay" – Found SF, 1995, www.foundsf.org

- Jerome A. Hart, "The Sand Lot and Kearneyism" – Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, www.sfmuseum.org

- Katie Dowd, "140 years ago, San Francisco was set ablaze during the city's deadliest race riots" – San Francisco Chronicle, www.sfgate.com