Locust (ethnic slur)

Locust (Chinese: 蝗蟲; pinyin: Huángchóng) is an ethnic slur against the Mainland Chinese people in Hong Kong.[1] The derogatory remark is frequently used in protest, social media, and localist publications in Hong Kong, especially when the topics involves the influx of mainland Chinese tourists, immigrants, parallel traders, and the pro-democracy movement.[2][3][4]

Origin

In 1901, English merchant Archibald John Little recorded the expression of comparing ethnic Chinese people to locusts, expressed by French Catholic priest Armand David. in his book, Mount Omi and beyond: A record of travel on the Tibetan border, Little referenced David's animosity toward the Chinese people:

...on this locust-like propensity of the Chinese to destroy every green thing wherever they penetrate, for when the trees are gone comes the turn of the scrub and bushes, then the grass, and at last the roots, until, finally, the rain washes down the accumulated soil of ages, and only barren rocks remain…[5]

In Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, "wong chung", the Cantonese word for locust, is used in a derogatory sense against mainland Chinese under the backdrop of ongoing tensions between Hongkongers and mainland China.[6]

Chinese people are called wong chung, locust in Cantonese, by local residents. The usage of the word began in Hong Kong local blogs and message boards such as HKGolden.[7] Popular songs with lyrics modified, containing derogatory slurs such as "locusts" and "Cheena" directed toward mainland Chinese people, were regularly produced and shared between online communities.[8] Mainland Chinese working and studying in Hong Kong regularly experience discrimination,[9] regardless of their level of assimilation. Hong Kong surveys indicated mainland Chinese speaking Cantonese were mocked due to their accents, denied work opportunities, and they suffered mental health issues.[10]

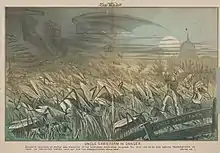

The term locust became prominent in 2012, when some local residents paid full-page advertisement, depicting mainland Chinese as locusts on local tabloid-newspaper Apple Daily HK.[11] The ethnic slur then gained widespread usage in subsequent protests against mainland Chinese immigrants, tourists, birth tourists, and parallel traders, where residences would chant and sing songs targeting mainland Chinese people.[9][12] Localist demonstrators organized "anti-locust protest", shouting slurs at mainland shoppers.[13] These provocative words sometimes lead to physical conflicts between the protesters and pedestrians.[9]

In Hong Kong, some people may consider the usage and discrimination toward mainland Chinese morally justified[11] due to Hong Kong's colonial history, cultural differences, and nostalgia toward British rule.[11][14] Some protesters choose to express their frustrations on ordinary mainlanders instead of the Chinese government. Due to the rising tribalism and nationalism in Hong Kong and China, the ethnic racism between Hong Kongers and mainlanders is reinforced and reciprocated.[5][7]

San Francisco-based writer Ling Woo Liu argued that the usage of ethnic slur alienated mainland Chinese people who are sympathetic toward Hong Kong's cause.[15] Chinese media Southern Weekly believed the grievance of Hong Kong people is generated by the economic stagnation, crowded living space, inadequate public services in recent years. The article stated that Hongkonger's anger is misdirected as mainlanders are used as the sole scapegoat by localist movements.[16]

References

- Maria Sala, Ilaria (7 July 2017). "Don't call them "locusts": They may one day be proud Hong Kong locals". Quartz.

- "Beware the power of racial slurs to dehumanise". South China Morning Post. 2014-03-12. Retrieved 2021-11-14.

- "Hong Kong's protesters distance themselves from anti-mainland movement". america.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-11-14.

- "Hong Kong advert calls Chinese mainlanders 'locusts'". BBC News. 2012-02-01. Retrieved 2021-11-14.

- Hung, Yu Yui (2014). "What melts in the "Melting Pot" of Hong Kong?". Asiatic: IIUM Journal of English Language and Literature. 8 (2): 57–87.

- Huang, Zheping (14 October 2016). "I'm no China cheerleader, but Hong Kong lawmakers' use of a racial slur was offensive and unnecessary". Quartz.

- "香港與內地的融合" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "支那STYLE擺明歧視". MetroUK (in Cantonese). 25 October 2012. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013.

- Kuo, Lily (3 November 2014). "The uglier side of Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement pits Chinese against Chinese". Quartz. Retrieved 2021-11-14.

- Sun, Fiona (2 October 2021). "Insulted, humiliated, shunned: Hong Kong's mainland Chinese immigrants face unending discrimination in struggle to feel at home, survey shows". South China Morning Post.

- Wong, Wai-Kwok (2015). "Discrimination against the mainland Chinese and Hong Kong's defense of local identity". AChina's New 21st Century Realities: Social Equity in a Time of Change: 23–37.

- Wu, Kane (17 October 2014). "As a mainlander, Hong Kong's protests inspire and sadden me". Quartz. Retrieved 2021-11-14.

- Ng, Kang-chung (17 February 2014). "Scuffles break out as protesters hurl slurs, abuse at mainland Chinese tourists". South China Morning Post.

- Kuo, Frederick (18 June 2019). "The Hong Kong conundrum". Asia Times.

- "No excuse for using slurs against mainlanders". South China Morning Post. 2014-03-18. Retrieved 2021-11-14.

- "焦虑的香港在纠偏 | 南方周末". www.infzm.com. Retrieved 2021-11-14.

Further reading

- Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, "Localists and “Locusts” in Hong Kong: Creating a Yellow-Red Peril Discourse," Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies: Vol. 2015: No. 2, Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mscas/vol2015/iss2/1