Hamengkubuwono IX

Hamengkubuwono IX or HB IX (12 April 1912 – 2 October 1988[lower-alpha 1]) was an Indonesian statesman and a Javanese royal who was the second vice president of Indonesia, the ninth sultan of Yogyakarta, and the first governor of the Special Region of Yogyakarta. Hamengkubuwono IX was also the Chairman of the first National Scout Movement Quarter and was known as the Father of the Indonesian Scouts.

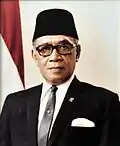

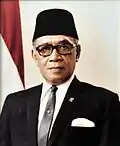

Sri Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX | |

|---|---|

ꦯꦿꦶꦯꦸꦭ꧀ꦡꦟ꧀ꦲꦩꦼꦁꦑꦸꦨꦸꦮꦟ꧇꧙꧇ | |

Official portrait, 1973 | |

| 2nd Vice President of Indonesia | |

| In office 23 March 1973 – 23 March 1978 | |

| President | Suharto |

| Preceded by | Mohammad Hatta |

| Succeeded by | Adam Malik |

| 1st Chief Minister for Economic and Financial Affairs of Indonesia | |

| In office 25 July 1966 – 28 March 1973 | |

| President | Sukarno Suharto |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Widjojo Nitisastro |

| 5th Deputy Prime Minister of Indonesia | |

| In office 6 September 1950 – 27 April 1951 | |

| President | Sukarno |

| Preceded by | Abdul Hakim |

| Succeeded by | Suwiryo |

| 5th Minister of Defense | |

| In office 4 August 1949 – 20 December 1949 | |

| President | Sukarno |

| Preceded by | Mohammad Hatta |

| Succeeded by | Abdul Halim |

| In office 3 April 1952 – 30 July 1953 | |

| President | Sukarno |

| Preceded by | Sukiman Wirjosandjojo |

| Succeeded by | Iwa Kusumasumantri |

| 1st Governor of Yogyakarta | |

| In office 4 March 1950 – 2 October 1988 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Paku Alam VIII |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1945–1953 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Indonesian War of Independence |

| 9th Sultan of Yogyakarta | |

| Reign | 18 March 1940 – 2 October 1988 |

| Predecessor | Hamengkubuwono VIII |

| Successor | Hamengkubuwono X |

| Born | Raden Mas Dorodjatun 12 April 1912 Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta Sultanate |

| Died | 2 October 1988 (aged 76) George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, D.C., United States |

| House | Hamengkubuwono |

| Signature |  |

Early life and education

Early life

Born as Gusti Raden Mas Dorodjatun, in Sompilan, Ngasem, Yogyakarta, Hamengkubuwono IX was the ninth son of Prince Gusti Pangeran Puruboyo —later titled Hamengkubuwono VIII— with his consort, Raden Ajeng Kustilah.[1][2] When he was three years old he was named Crown Prince to the Yogyakarta Sultanate after his father ascended to the throne.[3]

When he was four, he was sent away to live with the Mulder family, a Dutch family which lived in the Gondokusuman area. While living with the Mulder family, Hamengkubuwono IX was called by the name Henkie which was taken from the name of Prince Hendrik of the Netherlands.[3][4]

Education

He spent his school years in Yogyakarta, starting from Frobel School (kindergarten), and continuing to the Eerste Europe Lagere School which then moved to Neutrale Europeesche Lagere School. After completing his basic education, he continued his education to Hogere Burgerschool Semarang for a year before moving to Hogere Burgerschool Bandung.[3]

In 1930, he and his older brother, BRM – later known as Prabuningrat, after Hamengkubuwono IX's coronation – moved to the Netherlands. He started school at the Lyceum Haarlem, Netherlands. He was often called Sultan Henk when studying at the school.[3] After graduating in 1934, Hamengkubuwono IX and his older brother moved to Leiden, entering the college Rijksuniversiteit Leiden – Leiden University today – and took up the study of Indology, study of the colonial administration in the Indies.

However, he didn't finish his education, and had to return to his native land in 1939, following the start of World War II.[5]

Return to the Indies

After arriving in Batavia from the Netherlands in October 1939, Hamengkubuwono IX was picked up by his father directly to the Hotel des Indes. When an autonomous ruler was in Batavia, generally there were many agendas of activities that had to be fulfilled. One of the events attended by the royal family with Hamengkubuwono IX in Batavia was an invitation to dinner at the Palace of the Governor General of the Dutch East Indies.[6] While preparing to attend the invitation, Hamengkubuwono IX was pinned with Kyai Jaka Piturun's keris by his father.[7] This keris is generally passed on to the son of the ruler who is desired to become the crown prince. Therefore, this indicated that Hamengkubuwono IX would become the heir to the throne of the Sultanate of Yogyakarta.[8][9]

After attending the three-day agenda in Batavia, the royal family and Hamengkubuwono IX returned to Yogyakarta using the Eendaagsche Express train. On the way, his father fell ill and became unconscious. Arriving in Yogyakarta, the Sultan was immediately rushed to the Onder de Bogen Hospital and treated until the end of his life on 22 October 1939. Hamengkubuwono IX as crown prince then gathered his brothers and uncles to discuss who would become the next Sultan. All of his relatives agreed to appoint Hamengkubuwono IX as the next Sultan.

Coronation

Hamengkubuwono IX was crowned as Sri Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX on 18 March 1940, in accordance with the effective date of the political contract with the Dutch East Indies Government. Governor Lucien Adam crowned him for two titles at once. The first title is the title of Prince Adipati Anom Hamengku Negara Sudibya Raja Putra Narendra Mataram, his title as Crown Prince. After that, Sri Sultan Hamengkubuwana IX was crowned with the title Sampéyan Dalem Ingkang Sinuwun Kangjeng Sultan Hamengkubuwana Sénapati ing Ngalaga Abdurrahman Sayidin Panatagama Kalifatullah Ingkang Jumeneng Kaping Sanga.[10]

During his coronation speech, Hamengkubuwono recognized his Javanese origins and said "Even though I have tasted Western Education, I am still and will always be a Javanese."[11]

Reign

Negotiations with the Dutch

The 28-year-old young Sultan negotiated terms and conditions with the 60-year-old governor, Dr Lucien Adam, for four months from November 1939 to February 1940. The main points of contention were:

- The Sultan did not agree that his prime minister ("Patih Danureja") would also be an employee of the Netherlands to avoid a conflict of interest.

- The Sultan did not agree that half of his advisors would be selected by the Netherlands.

- The Sultan did not agree that his small army would receive direct orders from the Dutch army.

Eventually, the Sultan agreed to the proposal by the government of the Netherlands, and in February 1942, the Netherlands surrendered Indonesia to the invading Japanese army.

World War II

In 1942, the Dutch Colonial Government in Indonesia was defeated by the Japanese Imperial Army. Japan subsequently occupied the Dutch East Indies. Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX was given autonomy to run the government in his area under the Japanese Colonial Government. The position of Pepatih Dalem which previously had to be responsible to the Sultan and the Dutch Colonial Government now became only responsible to the Sultan.[12][13]

Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX was re-elected as Ruler of Yogyakarta on 1 August 1942 by the Commander in Chief of the Japanese Occupation Army in Jakarta and Yogyakarta became a Kochi (Special Region). In the midst of the large number of population taking into Rōmusha, the Sultan was able to prevent it by manipulating agricultural and livestock statistics. The Sultan proposed the construction of an irrigation canal that connects Progo River and Opak River so that rice fields can be irrigated throughout the year, which previously had a rain-fed system. This proposal was accepted and even assisted by funding for its construction. This irrigation channel was later called the Mataram Sewer and in Japanese it was called Gunsei Yosuiro (Yosuiro Canal). After the construction of the Mataram Sewers was completed, agricultural productivity increased so that the population used as Rōmusha was drastically reduced, although some were still brought in by the Colonial Government.[13][14]

Support for independence

Directly after the declaration of Indonesian independence at 17 August 1945, Hamengkubuwono IX together with Paku Alam VIII, the Prince of Pakualaman decided to support the newly formed Republic. Hamengkubuwono IX's support was immediately recognized by the Central Government with an appointment to the Life-Governorship of Yogyakarta with Paku Alam VIII as vice governor. Yogyakarta's status was also upgraded to that of Special Region. In addition, Hamengkubuwono IX served as Yogyakarta's military governor and was also minister of the state from 1945 to 1949.

The Dutch returned to lay claim to their former colony. Hamengkubuwono IX played a vital role in the resistance. In early 1946, the capital of Indonesia was quietly relocated to Yogyakarta, and the Sultan gave the new government some funding. When Indonesia first sought a diplomatic solution with the Dutch Government, Hamengkubuwono IX was part of the Indonesian delegation. On 21 December 1948, the Dutch successfully occupied Yogyakarta and arrested Sukarno and Hatta, Indonesia's first president and vice president. Hamengkubuwono IX did not leave Yogyakarta and continued to serve as governor. The Dutch intended to make Yogyakarta the capital of the new Indonesian federal state of Central Java and to appoint the sultan as head of state, but Hamengkubuwono refused to cooperate.[15] The Dutch viewed him with suspicion and at one stage began to entertain the idea that Hamengkubuwono IX was either planning to make Yogyakarta a completely autonomous region or setting his eyes on the leadership of the Republic.[16]

1 March General Offensive

In early 1949, Hamengkubuwono IX conceived the idea of a major offensive to be launched against Yogyakarta and the Dutch troops occupying it. The purpose of this offensive was to show to the world that Indonesia still existed and that it was not ready to surrender. The idea was suggested to General Sudirman, the Commander of the Indonesian Army and received his approval. In February 1949, Hamengkubuwono IX had a meeting with then Lieutenant Colonel Suharto, the man chosen by Sudirman to be the field commander for the offensive. After this discussion, preparations were made for the offensive. This involved intensified guerilla attacks in villages and towns around Yogyakarta so as to make the Dutch station more troops outside of Yogyakarta and thin the numbers in the city itself. On 1 March 1949 at 6 am, Suharto and his troops launched the 1 March General Offensive. The offensive caught the Dutch by surprise. For his part, Hamengkubuwono IX allowed his palace to be used as a hide out for the troops. For 6 hours, the Indonesian troops had control of Yogyakarta before finally retreating. The offensive was a great success, inspiring demoralized troops all around Indonesia. On 30 June 1949, the retreating Dutch forces handed over authority over Yogyakarta to Hamengkubuwono IX.[17] On 27 December, immediately after the transfer of sovereignty was signed by Queen Juliana in Dam Palace in Amsterdam, High Commissioner A.H.J. Lovink transferred his powers to Hamengkubuwono during a ceremony in Jakarta in Koningsplein Palace, later renamed Merdeka Palace.[18]

Minister in the Indonesian Government

After Indonesia's Independence was recognized by the Dutch, Hamengkubuwono IX continued to serve in government. In addition to continuing his duties as Governor of Yogyakarta, Hamengkubuwono IX continued to serve in the Indonesian Government as Minister.[19]

Hamengkubuwono IX served as Minister of Defense and Homeland Security Coordinator (1949–1951 and 1953), vice premier (1951), chairman of the State Apparatus Supervision (1959), chairman of the State Audit Board (1960–1966), and Coordinating Minister for Development while concurrently holding the position of Minister of Tourism (1966). In addition to these positions, Hamengkubuwono IX held the positions of chairman of the National Sports Committee of Indonesia (KONI) and chairman of the Tourism Patrons Council.

Transition from old order to new order

During the G30S Movement, in the course of which six generals were kidnapped from their homes and killed, Hamengkubuwono IX was present in Jakarta. That morning, with President Sukarno's location still uncertain, Hamengkubuwono was contacted by Suharto, who was now a major general and the commander of Kostrad (Army Strategic Command) for advice. Suharto suggested that because Sukarno's whereabouts are still unknown, Hamengkubuwono IX should form a provisional government to help counter the movement.[20] Hamengkubuwono IX rejected the offer and contacted one of Sukarno's many wives who confirmed Sukarno's whereabouts.

After Suharto had received Supersemar (Order of the Eleventh of March) in March 1966, Hamengkubuwono IX and Adam Malik joined him in a triumvirate to reverse Sukarno's policies. Hamengkubuwono IX was appointed Minister of Economics, Finance, and Industry and charged with rectifying Indonesia's Economic problems. He would hold this position until 1973.

Vice presidency

Appointment

Ever since Mohammad Hatta resigned as vice-president in December 1956, the position had remained vacant for the rest of Sukarno's time as president. When Suharto was formally elected to the presidency in 1968 by the People's Consultative Assembly, it continued to remain vacant. Finally in March 1973, Hamengkubuwono IX was elected as vice president alongside Suharto who had also been re-elected to a second term as president. He retained his post as Yogyakarta Governor during his vice-presidential tenure.

Hamengkubuwono IX's election was not a surprise as he was a popular figure in Indonesia. He was also a civilian and his election to the vice presidency was hoped to complement Suharto's military background. Despite being officially elected in 1973, it can be said that Hamengkubuwono IX had been the de facto vice president beforehand as he regularly assumed the leadership of the country whenever Suharto was out of the country.[21] As vice president, Hamengkubuwono IX was put in charge of welfare and was also given the duty of supervising economic development.[22]

Retirement

It was expected that the Suharto and Hamengkubuwono IX duet would be retained for another term. However, Hamengkubuwono IX had become disillusioned with Suharto's increasing authoritarianism and the increasing corruption.[23]

These two elements were also recognized by protesters who had demanded that Suharto not stand for another term as president. These protests reached its peak in February 1978, when students of Bandung Technological Institute (ITB) published a book giving reasons as to why Suharto should not be elected president. In response, Suharto sent troops to take over the campus and issued a ban on the book. Hamengkubuwono could not accept Suharto's actions . In March 1978, Hamengkubuwono rejected his nomination as vice president by the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR). Suharto asked Hamengkubuwono to change his mind, but Hamengkubuwono continued to reject the offer and cited health as his reason for not accepting the nomination.[24]

Suharto took Hamengkubuwono IX's rejection personally and in his 1989 autobiography would claim credit for conceiving 1 March General Offense.

Other activities

Scout movement

Hamengkubuwono IX had been active with Scouts from the days of the Dutch colonial government and continued to look after the movement once Indonesia became independent. In 1968, Hamengkubuwono IX was elected Head of the national Scout movement. Hamengkubuwono IX was also awarded the Bronze Wolf, the only distinction of the World Organization of the Scout Movement, awarded by the World Scout Committee for exceptional services to world Scouting, in 1973.[25][26]

Chairman of the national sports committee

From the beginning of independence, he had an interest in forming a national sports center organization to show national identity, which was related to sending Indonesian athletes in the early days of the war of independence to the 1948 Olympics.[27] At its peak, he was trusted to lead and pioneer the formation of National Sports Committee of Indonesia and became the longest-serving chairman in history and has produced proud achievements for Indonesia in international sporting events.

Death

During a visit to Washington D.C. in 1988, Hamengkubuwono IX experienced sudden, internal bleeding. He was brought to the George Washington University Medical Center, where he died on the evening of 2 October 1988, or the following morning, 3 October in Indonesia. His body was flown back to Yogyakarta and buried in the royal mausoleum of the Mataram monarchs in Imogiri. There is a special museum dedicated to him in the sultan's palace (kraton) in Yogyakarta. He was also given the title National Hero of Indonesia, a distinction for Indonesian patriots. His son, Raden Mas Herdjuno Darpito, succeeded him and took the regnal name of Hamengkubuwono X.

One of the two symbolically important banyan trees, the Kiai Dewandaru planted during the reign of Sri Sultan Hamengkubuwono I, coincidentally fell in the Alun-Alun Lor (Northern Parade Square) concurrently with the funerary rites of Hamengkubuwono IX; this was attributed by the Kejawèn Javanese as a sign of the immense grief of even the lands of the kingdom themselves. The banyan was replanted with the approval of Hamengkubuwono X, although it is diminutive beside the centuries-old Kiai Wijayadaru on the east flank.

Marital status

Hamengkubuwono IX never had a queen consort during his reign; preferring instead to take four concubines by whom he had 21 children.

Miscellaneous

Hamengkubuwono IX was a fan of Chinese Silat movies and novels.[28] He also enjoyed cooking and headed an unofficial Chinese Silat club which included Cabinet Ministers as its members.

Honours

National honours

Star of the Republic of Indonesia, 2nd Class (Indonesian: Bintang Republik Indonesia Adipradana) (20 May 1967) [29]

Star of the Republic of Indonesia, 2nd Class (Indonesian: Bintang Republik Indonesia Adipradana) (20 May 1967) [29] Star of Mahaputera, 1st Class (Indonesian: Bintang Mahaputera Adipurna) (20 May 1967) [30]

Star of Mahaputera, 1st Class (Indonesian: Bintang Mahaputera Adipurna) (20 May 1967) [30] Star of Mahaputera, 2nd Class (Indonesian: Bintang Mahaputera Adipradana) (15 February 1961) [31]

Star of Mahaputera, 2nd Class (Indonesian: Bintang Mahaputera Adipradana) (15 February 1961) [31] Guerrilla Star (Indonesian: Bintang Gerilya)

Guerrilla Star (Indonesian: Bintang Gerilya) Star of Bhayangkara, 2nd Class (Indonesian: Bintang Bhayangkara Pratama)

Star of Bhayangkara, 2nd Class (Indonesian: Bintang Bhayangkara Pratama).gif) Indonesian Armed Forces "8 Years" Service Star (Indonesian: Bintang Sewindu Angkatan Perang Republik Indonesia)

Indonesian Armed Forces "8 Years" Service Star (Indonesian: Bintang Sewindu Angkatan Perang Republik Indonesia) Anniversary of the Struggle for Independence Medal (Indonesian: Satyalancana Peringatan Perjuangan Kemerdekaan)

Anniversary of the Struggle for Independence Medal (Indonesian: Satyalancana Peringatan Perjuangan Kemerdekaan) Military Long Service Medal (Indonesian: Satyalancana Kesetiaan)

Military Long Service Medal (Indonesian: Satyalancana Kesetiaan) 1st Independence War Medal (Indonesian: Satyalancana Perang Kemerdekaan I)

1st Independence War Medal (Indonesian: Satyalancana Perang Kemerdekaan I) 2nd Independence War Medal (Indonesian: Satyalancana Perang Kemerdekaan II)

2nd Independence War Medal (Indonesian: Satyalancana Perang Kemerdekaan II)

Foreign honours

Malaysia :

Malaysia :

Honorary Grand Commander of the Order of Loyalty to the Crown of Malaysia (1972)[32]

Honorary Grand Commander of the Order of Loyalty to the Crown of Malaysia (1972)[32]

Germany:

Germany:

Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

Netherlands:

Netherlands:

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion Grand Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau (1940)

Grand Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau (1940)

Thailand:

Thailand:

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) Knight Grand Cross of the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant

Knight Grand Cross of the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant

Japan:

Japan:

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (1974)

Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (1974)

Gallery

Official portrait, as Vice President

Official portrait, as Vice President Official portrait, as Vice President (another version)

Official portrait, as Vice President (another version).jpg.webp) Official portrait, as Vice President (another earlier version)

Official portrait, as Vice President (another earlier version)%252C_p53.jpg.webp) Hamengkubuwono IX in 1954

Hamengkubuwono IX in 1954%252C_p10.jpg.webp) Hamengkubuwono IX in 1952

Hamengkubuwono IX in 1952 Sukarno (left) and Hamengkubuwono IX (right)

Sukarno (left) and Hamengkubuwono IX (right) Hamengkubuwono IX in the IDR10,000 banknote issued in 1992

Hamengkubuwono IX in the IDR10,000 banknote issued in 1992

Sources

- Roem, Mohammad. 1982. Tahta untuk Rakyat (English: A Throne for the People), Jakarta: Gramedia – Biography of Hamengkubuwono IX.

- Soemardjan, S. 1989. In Memoriam: Hamengkubuwono IX, Sultan of Yogyakarta, 1912–1988 Indonesia. 47:115–117.

- John Monfries. 2015. A Prince in a Republic: The Life of Sultan Hamengku Buwono IX of Yogyakarta, Singapore: ISEAS, ISBN 978-981-4519-38-0

References

- Suyono, Seno Joko; Hidayat, Dody; Widiarsi, Agustina (2018). Hamengku Buwono IX (in Indonesian) (3rd ed.). Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-602-6208-38-5. OCLC 1091075597.

- Monfries, John (2015). A prince in a republic : the life of Sultan Hamengku Buwono IX of Yogyakarta. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 28. ISBN 978-981-4519-39-7. OCLC 907618259.

- "Raja Raja | Karaton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat - Kraton Jogja". www.kratonjogja.id. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Amin, Al (12 April 2012). "Hamengku Buwono IX sering kos di orang Belanda". merdeka.com. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Monfries, John (2015). A prince in a republic : the life of Sultan Hamengku Buwono IX of Yogyakarta. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 49. ISBN 978-981-4519-39-7. OCLC 907618259.

- Roem, Mohamad; Atmakusumah (2011). Takhta untuk rakyat : celah-celah kehidupan Sultan Hamengku Buwono IX (4th revised ed.). Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-979-22-6767-9. OCLC 729721382.

- Pratama, Fajar (2015). "Penyempurnaan 2 Keris dan Pengubahan Perjanjian Kerajaan Dinilai Punya 1 Maksud".

- Suyono, Seno Joko; Hidayat, Dody; Widiarsi, Agustina (2018). Hamengku Buwono IX (3rd ed.). Jakarta. ISBN 978-602-6208-38-5. OCLC 1091075597.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Roem, Mohamad; Atmakusumah (2011). Takhta untuk rakyat : celah-celah kehidupan Sultan Hamengku Buwono IX (4th revised ed.). Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 978-979-22-6767-9. OCLC 729721382.

- Roem, Mohamad; Atmakusumah (2011). Takhta untuk rakyat : celah-celah kehidupan Sultan Hamengku Buwono IX (4th revised ed.). Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. pp. 43 & 46. ISBN 978-979-22-6767-9. OCLC 729721382.

- "Sri Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX, Bangsawan Yang Demokratis". Tokohindonesia. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- Suyono, Seno Joko (2015). Hamengku Buwono IX: Pengorbanan Sang Pembela Republik. p. 72. ISBN 978-602-6208-38-5.

- Roem, Mohamad (1982). Takhta untuk Rakyat: Celah-Celah Kehidupan Sultan Hamengku Buwono IX. Jakarta: PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-979-2267-67-9.

- Suyono, Seno Joko (2015). Hamengku Buwono IX: Pengorbanan Sang Pembela Republik. Jakarta. ISBN 978-602-6208-38-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Van den Doel, H.W., Afscheid van Indië. De val van het Nederlandse Imperium in Azië [Farewell to the Indies. The Fall of the Dutch Empire in Asia] (Amsterdam: Prometheus 2001), page 337.

- Elson, Robert (2001). Suharto: A Political Biography. UK: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. p. 33. ISBN 0-521-77326-1.

- Van den Doel, H.W., Afscheid van Indië. De val van het Nederlandse Imperium in Azië [Farewell to the Indies. The Fall of the Dutch Empire in Asia] (Amsterdam: Prometheus 2001), page 344.

- Van den Doel, H.W., Afscheid van Indië. De val van het Nederlandse Imperium in Azië [Farewell to the Indies. The Fall of the Dutch Empire in Asia] (Amsterdam: Prometheus 2001), page 351.

- Van den Doel, H.W., Afscheid van Indië. De val van het Nederlandse Imperium in Azië [Farewell to the Indies. The Fall of the Dutch Empire in Asia] (Amsterdam: Prometheus 2001), page 284.

- Hughes, John (2002) [1967]. The End of Sukarno: A Coup That Misfired: A Purge That Ran Wild (3rd ed.). Singapore: Archipelago Press. p. 68. ISBN 981-4068-65-9.

- Elson, Robert (2001). Suharto: A Political Biography. UK: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. p. 167. ISBN 0-521-77326-1.

- ""Wakil Presiden, antara Ada dan Tiada" (The Vice Presidency, between Existence and Non-Existence"". Kompas. 8 May 2004. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- Elson, Robert (2001). Suharto: A Political Biography. UK: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. p. 225. ISBN 0-521-77326-1.

- "Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX". Setwapres. Archived from the original on 16 March 2005. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- Ratna, Dewi (31 May 2016). "Prestasi keren Bapak Pramuka Indonesia, Sri Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX | merdeka.com". merdeka.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- Haru Matsukata Reischauer (1986). Samurai and Silk: A Japanese and American Heritage. Harvard University Press. pp. 317–. ISBN 978-0-674-78801-5.

- "Sejarah koni". koni.or.id (in Indonesian). 30 June 2023.

- "Komunitas Pendekar Penggebuk Anjing". Kompas. Archived from the original on 12 January 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- Daftar WNI yang Menerima Tanda Kehormatan Bintang Republik Indonesia 1959 - sekarang (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Daftar WNI yang Mendapat Tanda Kehormatan Bintang Mahaputera tahun 1959 s.d. 2003 (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Daftar WNI yang Mendapat Tanda Kehormatan Bintang Mahaputera tahun 1959 s.d. 2003 (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- "Senarai Penuh Penerima Darjah Kebesaran, Bintang dan Pingat Persekutuan Tahun 1972" (PDF).

External links

- profile on Tokohindonesia.com Archived 5 February 2004 at the Wayback Machine (in Indonesian)

- profile on pdat.co.id (in Indonesian)