China painting

China painting, or porcelain painting,[lower-alpha 1] is the decoration of glazed porcelain objects such as plates, bowls, vases or statues. The body of the object may be hard-paste porcelain, developed in China in the 7th or 8th century, or soft-paste porcelain (often bone china), developed in 18th-century Europe. The broader term ceramic painting includes painted decoration on lead-glazed earthenware such as creamware or tin-glazed pottery such as maiolica or faience.

Typically the body is first fired in a kiln to convert it into a hard porous biscuit or bisque. Underglaze decoration may then be applied, followed by glaze, which is fired so it bonds to the body. The glazed porcelain may then be painted with overglaze decoration and fired again to bond the paint with the glaze. Most pieces use only one of underglaze or overglaze painting, the latter often being referred to as "enamelled". Decorations may be applied by brush or by stenciling, transfer printing and screen printing.

Porcelain painting was developed in China and later taken up in Korea and then Japan. Decorated Chinese porcelain from the 9th century has been found in the Middle East. Porcelain for trade with this region often has Islamic motifs. Trade with Europe began in the 16th century. By the early 18th century European manufacturers had discovered how to make porcelain. The Meissen porcelain factory in Saxony was followed by other factories in Germany, France, the UK and other European countries. Technology and styles evolved. The decoration of some hand-painted plates and vases from the 19th century resembles oil paintings. In the later part of the 19th century china painting became a respectable hobby for middle-class women in North America and Europe. More recently interest has revived in china painting as a fine art form.

Technical aspects

Bodies

The Chinese define porcelain[lower-alpha 2] as a type of pottery that is hard, compact and fine-grained, that cannot be scratched by a knife, and that resonates with a clear, musical note when hit. It need not be white or translucent.[4] This porcelain is made from kaolin.[5] The clay is mixed with petuntse, or more commonly feldspar and quartz.[3] The glaze is prepared from petuntse mixed with liquid lime, with less lime in the higher-quality glazes. The lime gives the glaze a hint of green or blue, a brilliant surface and a sense of depth.[6] Hard-paste porcelain is fired to temperatures of 1,260 to 1,300 °C (2,300 to 2,370 °F).[7]

Soft-paste porcelain was invented in Europe.[7] Soft-paste porcelain made in England from about 1745 used a white-firing clay with the addition of a glassy frit.[8] The frit is a flux that causes the piece to vitrify when it is fired in a kiln. Soft-paste porcelain is fired to 1,000 to 1,100 °C (1,830 to 2,010 °F).[7] The kiln must be raised to the precise temperature where the piece will vitrify, but no higher or the piece will sag and deform. Soft-paste porcelain is translucent and can be thinly potted. After firing it has similar appearance and properties to hard-paste porcelain.[8]

The use of calcined animal bones in porcelain was suggested in Germany in 1689, but bone china was developed in England, with the first patent taken out in 1744.[8] Bone china was perfected by Josiah Spode (1733–1797) of Stoke-upon-Trent in England.[9] The basic formula is 50% calcined cattle bone, 25% Cornish stone and 25% china clay. The stone and clay are both derived from granite. The stone is a feldspathic flux that melts and reacts with the other ingredients. The resulting material is strong, white and translucent, and resonates when struck.[10] It is fired at a medium temperature, up to 1,200 °C (2,190 °F), which gives it a much better body than soft-paste objects with a glassy frit.[8] The firing temperature is lower than for hard-paste porcelain, so more metal oxides can retain their composition and bond to the surface. This gives a wider range of colors for decoration.[10]

Earthenware pottery including tin-glazed pottery, Victorian majolica, Delftware and faience. Earthenware is opaque, with a relatively coarse texture, while porcelain is translucent, with a fine texture of minute crystals dispersed in a transparent glassy matrix.[5] Industrial manufacturers of earthenware pottery biscuit-fire the body to the maturing range of the body, typically 1,100 to 1,160 °C (2,010 to 2,120 °F), then apply glaze and glaze-fire the piece at a lower temperature of about 1,060 to 1,080 °C (1,940 to 1,980 °F).[11]

With stoneware and porcelain the body is usually biscuit fired to 950 to 1,000 °C (1,740 to 1,830 °F), and then glost or glaze fired to 1,220 to 1,300 °C (2,230 to 2,370 °F). Because the glost temperature is higher than the biscuit temperature, the glaze reacts with the body. The body also releases gases that bubble up through the glaze, affecting the appearance.[12]

The same techniques are used to paint the various types of porcelain and earthenware, both underglaze and overglaze, but different pigments are used due to the different body characteristics and firing temperatures. Generally earthenware painting uses bolder, simpler designs, while china painting may be finer and more delicate.[5]

Underglaze painting

Traditional porcelain in China included painting under the glaze as well as painting over the glaze.[13] With underglaze painting, as its name implies, the paint is applied to an unglazed object, which is then covered with glaze and fired. A different type of paint is used from that used for overglaze painting.[14] The glaze has to be subject to very high temperatures to bond to the paste, and only a very limited number of colors can stand this process. Blue was commonly used under the glaze and other colors over the glaze, both in China and in Europe, as with English Royal Worcester ware.[13] Most pieces use only one of underglaze or overglaze painting.[15]

Underglaze painting requires considerably more skill than overglaze, since defects in the painting will often become visible only after the firing.[14] During firing even refractory paints change color in the great heat. A light violet may turn into a dark blue, and a pale pink into a brown-crimson. The artist must anticipate these changes.[16] With mazarine blue underglazing the decoration is typically fairly simple, using outline extensively and broad shading. The Japanese were known for their skill in depicting flowers, plants and birds in underglaze paintings that used the fewest possible brushstrokes.[17]

Overglaze painting

Overglaze china paints are made of ground mineral compounds mixed with flux. Paints may contain expensive elements including gold. The flux is a finely-ground glass, similar to porcelain glaze. The powdered paint is mixed with a medium, typically some type of oil, before being brushed onto the glazed object.[18] The technique is similar to watercolor painting.[19] One advantage of overglaze china painting compared to oil or watercolor is the paint may be removed with a slightly wetted brush while the color is still moist, bringing back the original ground.[20] Pieces with overglaze painting are often referred to as "enamelled".[15]

Open mediums do not dry in the air, while closed mediums do.[18] An artist may prefer a medium that stays fluid for some time, may want one that dries hard, or may want a medium that remains somewhat sticky. If the medium dries hard the artist can build up layers of color, which will fuse together in a single firing. This can create unusual intensity or depth of color. If the medium remains sticky the artist can add to the design by dusting more color onto the surface, or can dust on an overglaze powder to create a high gloss surface.[21]

The artist may begin by sketching their design with a china marker pencil. When the painted object is fired in a kiln, the china marker lines and the medium evaporate.[18] The color particles melt and flatten on the glaze surface, and the flux bonds them to the glaze. At sufficient heat the underlying glaze softens, or "opens". The color is strongly bonded to the glaze and the surface of the finished object is glossy.[21]

Mechanical approaches

Stenciling was in use in the 17th century. A pattern is cut out of a paper form, which is placed on the ceramic. Paint is then dabbed through the stencil.[22] Transfer printing from engraved or etched copperplates or woodblocks dates to around 1750. The plate is painted with an oil-and-enamel pigment. The surface is cleaned, leaving the paint in the cut grooves. The paint is then transferred to "potter's tissue", a thin but tough tissue paper, using a press. The tissue is then positioned face-down over the ceramic and rubbed to transfer the paint to the surface.[23] This technique was introduced for both underglaze and overglaze transfer in Worcester in the mid-1750s.[24]

Lithography was invented in 1797, at first used in printing paper images. An image is drawn with a greasy crayon on a smooth stone or zinc surface, which is then wetted. The water remains on the stone but is repelled by the grease. Ink is spread on and is repelled by the water but remains on the grease. Paper is then pressed onto the slab. It picks up the ink from the grease, thus reproducing the drawing. The process can be repeated to make many copies.[25] A multicolored print could be made using different blocks for different colors. For ceramics, the print was made onto duplex paper, with a thin layer of tissue paper facing a thicker layer of paper. A weak varnish was painted on the ceramic surface, which could be slightly curved, then the duplex paper pressed onto the surface. The tissue paper was soaked off before firing. Later techniques were developed to photographically copy images onto lithograph plates.[25] The technique, with its ability to transfer fine detail, is considered most suitable for onglaze decoration, although it has been used for underglaze images.[25]

The roots of natural sponges were used in Scotland to make crude stamps to decorate earthenware pottery in the 19th century and early 20th century.[26] Rubber stamps were introduced in the 20th century to decorate porcelain and bone china with gold lustred borders.[25]

Screen printing was first introduced in Japan in the early 18th century, said to be the invention of Yutensai Miyassak.[27] The early Japanese version was a refinement to stenciling that used human hairs to hold together parts of the stencil, such as the outside and center of a circle, so that visible bridges could be eliminated. Eventually the technique evolved to use fine screens, with some areas blocked by a film and some lines or areas left open to allow paint to pass through. Techniques were developed to transfer images to screens photographically. The process was in use for ceramics by the mid-20th century, and is now the main way of decorating ceramics. It can be used to print curved shapes such as mugs with underglaze, onglaze, glaze, wax resist and heated thermoplastic colors.[25]

East Asian porcelain

China

Possibly, as some authors claim, porcelain was already being made during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) in an attempt to make vessels similar to the glass vessels that were being imported from Syria and Egypt at the time.[28] Certainly porcelain was being made in China in the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD). Over the years that followed the quality of the porcelain, the design and decoration became extremely refined. The pieces were thin and finely made, with subtle glazes, and later with elaborate painted decorations.[3] The Chinese began exporting porcelain throughout medieval Continental Asia and the Near East in the 9th century.[29] By the time of the Song dynasty (960–1279) the porcelain makers had achieved a high level of skill. Some experts consider their work to be unsurpassed in its purity of design.[30]

The Ding kilns in northern China began production early in the 8th century, where they produced sophisticated and beautiful porcelains and developed innovative kiln stacking and firing techniques.[31] Ding ware had white bodies, and typically had an ivory-white glaze.[32] However, some Ding ware had monochrome black, green and reddish brown glazes. Some were decorated with the sgraffito method, where surface layers were scaped away to expose a ground with a different color.[33] Jingdezhen was among the first porcelain manufacturing centers in the south of China, with ready access to kaolin and petunse. In its day it was the world's most important center of porcelain production. Jingdezhen ware includes the famous decorated Qingbai pieces with shadow-blue glazes. Under the Yuan dynasty the use of underglaze cobalt blue decoration became popular.[31] During the Ming dynasty (1369-1644) production of blue and white and red and white ceramics peaked.[34] The Jingdezhen artisans developed and perfected use of overglaze enamels in the second half of the 15th century. They excelled in their floral, abstract or calligraphic designs.[35]

Tang dynasty glazed earthenware c. 675-750

Tang dynasty glazed earthenware c. 675-750 Song dynasty (960-1279 AD) Ding ware porcelain bottle, iron-tinted under-glaze decoration

Song dynasty (960-1279 AD) Ding ware porcelain bottle, iron-tinted under-glaze decoration Jingdezhen, Yuan dynasty, foliated dish with underglaze blue design

Jingdezhen, Yuan dynasty, foliated dish with underglaze blue design Jingdezhen blue and white ware c. 1335

Jingdezhen blue and white ware c. 1335

Japan

The Japanese began to make porcelain early in the 17th century, learning from Chinese and Korean craftsmen how to fire the pieces and make underglaze blue cobalt decoration and overglaze enamel painting. In the mid-17th century the Japanese found a growing market from European traders who were unable to obtain Chinese porcelain due to political upheavals.[35] Brightly-coloured Japanese export porcelain made around the town of Arita were called Imari porcelain ware by the Europeans, after the shipping port. Porcelain only painted in underglaze blue is traditionally called Arita ware. The craftsman Sakaida Kakiemon developed a distinctive style of overglaze enamel decoration, typically using iron red, yellow and soft blue. Kakiemon-style decorations included patterns of birds and foliage, and influenced designs used in European factories.[36] The very refined Nabeshima ware and Hirado ware were not exported until the 19th century, but used for presentation wares among Japan's feudal elite.

Imari ware porcelain bowl c. 1640

Imari ware porcelain bowl c. 1640 Kakiemon dish, Arita, porcelain with overglaze enamels c. 1670

Kakiemon dish, Arita, porcelain with overglaze enamels c. 1670 Imari ware, Edo period, overglaze enamel

Imari ware, Edo period, overglaze enamel Brush holder with Dutchmen, Arita ware, late 18th to early 19th century

Brush holder with Dutchmen, Arita ware, late 18th to early 19th century Hirado ware ewer, Japan, late 19th century

Hirado ware ewer, Japan, late 19th century

Korea

Chinese ceramics began to be exported to Korea in the 3rd century. During the Goryeo period (918–1392) there was high demand for Chinese porcelain, and Korean potters used the imports as models. Distinctively Korean designs had emerged by the end of the 12th century, and the white porcelain of the reign of King Sejong of Joseon is quite unique. In 1424 there were 139 kilns in Korea producing porcelain.[35] In 1592 Japan invaded Korea and took four hundred potters as prisoners to Japan. The Korean porcelain industry was destroyed while the Japanese industry boomed. The 1636 Manchu invasion caused further damage.[35] The industry recovered and produced new forms with white or white and blue glaze. In the late 19th century the loss of state support for the industry and the introduction of printed transfer decoration caused the traditional skills to be lost.[35]

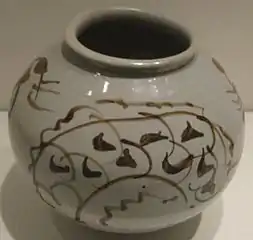

Joseon porcelain pot, iron oxide pattern of plum blossom, and Bamboo

Joseon porcelain pot, iron oxide pattern of plum blossom, and Bamboo Joseon dynasty porcelain jar, 17th century, iron-brown underglaze decoration

Joseon dynasty porcelain jar, 17th century, iron-brown underglaze decoration Joseon dynasty porcelain bottle, 19th century, blue & white

Joseon dynasty porcelain bottle, 19th century, blue & white

Middle East

Some writers suspect that porcelain may have been independently invented in Persia alongside China, where it has been made for many centuries, but the Persian word chini implicitly acknowledges its origins in China.[37] Others say the use of cobalt blue as a pigment for painting pottery was developed in the Middle East, and adopted in China for painting porcelain.[31] However, this has been disputed, since the earliest Middle-Eastern pottery with cobalt blue decoration, from Samarra in Iraq in the 9th century, has Chinese shapes. At that time the potters in the region did not have the technology to make high-fire underglaze porcelain. It appears that the white glazed pottery with blue decoration was in imitation of imported porcelain from China.[38]

Chinese porcelain was prized by wealthy people in the Middle East from the time of the Tang dynasty.[39] A large collection from the Ottoman sultans Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent is held by the Topkapı Palace museum in Istanbul.[40] Another large collection of 805 pieces of Chinese porcelain, donated to the Ardabil Shrine by Shah Abbas I of Persia in 1607–08, is now held in Tehran's National Museum of Iran.[41] Blue and white Chinese porcelains from the 14th to 16th centuries have also been found in peasant houses in Syria. Often the porcelain was designed for the market, with decorative designs that included prayers and quotations from the Koran in Arabic or Persian script.[40] Large amounts of Ming porcelain had also been found in Iraq and Egypt, and also in Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, India and East Africa.[42]

European exports

In the 16th century the Portuguese developed a limited trade in commonplace blue-and-white ware manufactured in China. In 1604 the Dutch captured a Portuguese carrack with about 100,000 porcelain items. These were auctioned at Amsterdam in August 1604 to buyers from across Europe.[43] Over the period from 1604 to 1657 the Dutch may have brought 3,000,000 pieces of porcelain to Europe. Political upheavals then cut off most of the trade of porcelain from China until 1695. The Japanese began to produce ware for export in 1660, but the supply was uncertain.[43] Trade with China reopened at the end of the 17th century, but the Dutch had lost their monopoly. A French ship reached Canton in 1698, and an English ship in 1699.[44] In the years that followed large quantities of porcelain manufactured in China for trade purposes were imported to Europe, much of it in English ships.[45]

Jingdezhen production expanded to meet the demand for export porcelain. The Jesuit François Xavier d'Entrecolles wrote of Jingdezhen in 1712, "During a night entrance, one thinks that the whole city is on fire, or that it is one large furnace with many vent holes."[34] The European traders began to supply models to show the manufacturers the form and decoration they required for tableware items unfamiliar to the Chinese.[46] The French Jesuits provided paintings, engravers, enamels and even the painters themselves to the Imperial court, and these designs found their way into porcelain decoration. Colorful enamel paints, used in German tin-glazed pottery, gave rise to new techniques such as famille rose coloring in Chinese porcelain.[47] Designs of European origin found their way onto many porcelain items made in China for export to Europe.[48] At least 60 million pieces of Chinese porcelain were imported to Europe in the 18th century.[48]

European manufacturing

A first attempt to manufacture porcelain in Europe was undertaken in Florence, Italy in the late 16th century, sponsored by Francesco I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. The "Medici porcelain" did not contain china clay, and was only made in small quantities. In the late 17th century Louis Poterat tried to manufacture porcelain at Rouen, France. Little of this has survived.[7] Tea drinking became fashionable in Europe at the start of the 18th century, and created increasing demand for Oriental-style porcelain.[49]

Germany

The Meissen porcelain factory near Dresden in Saxony was the first to successfully manufacture hard-paste porcelain in Europe. Painted porcelain wares that imitated oriental designs were being produced after 1715.[49] Johann Joachim Kändler (1706–75) was the most famous sculptor at Meissen, creating vigorous models of figures and groups.[50] The pieces had bright glazes and were painted in enamels with strong colors.[51] Meissen's processes were carefully guarded from competitors.[49] The secrets gradually leaked out, and factories were established in Prussia and at Vienna by the 1720s. After Saxony was defeated in the Seven Years' War (1756–63) the methods of making porcelain became widely known.[52] By the late 18th century there were twenty-three porcelain factories in Germany. The Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory in Munich was renowned for its delicate modeling and fine decoration.[52]

Meissen hard porcelain teapots c. 1720 decorated in the Netherlands c. 1735

Meissen hard porcelain teapots c. 1720 decorated in the Netherlands c. 1735 Meissen centerpiece and stand c. 1737 modeled by Johann Joachim Kändler

Meissen centerpiece and stand c. 1737 modeled by Johann Joachim Kändler Nymphenburg, Franz Anton Bustelli c. 1760

Nymphenburg, Franz Anton Bustelli c. 1760 Frankenthal, Johann Friedrich Lück, couple with bagpipes and hurdy-gurdy c. 1760

Frankenthal, Johann Friedrich Lück, couple with bagpipes and hurdy-gurdy c. 1760 Nymphenburg plates 1899

Nymphenburg plates 1899

France

Factories also opened in France and England, and porcelain wares began to be produced in higher volumes at lower prices.[49] In France, soft-paste porcelain was produced at Saint-Cloud from the 1690s. The Saint-Cloud painters were given the license to innovate, and produced lively and original designs, including blue-and-white pieces in the Chinese style and grotesque ornaments. A factory for white tin-glazed soft porcelain was founded at Chantilly around 1730. Many of its pieces was based on Kakiemon designs, using the Kakiemon colors of iron red, pale yellow, clear blue and turquoise green. Soft-paste porcelain was also made at Mennecy-Villeroy and Vincennes-Sèvres, and hard-paste porcelain was made at Strasbourg.[53]

Vincennes-Sèvres became the most famous porcelain factory in Europe in the later 18th century. It was known for its finely modeled and brightly colored artificial flowers, used to decorate objects such as clocks and candelabra.[54] The factory at Sèvres was nationalized in 1793 after the French Revolution. After 1800 it stopped producing soft-paste and standardized on an unusually hard type of hard-paste using china clay from Saint-Yrieix, near Limoges. The factory produced many different painted designs for decoration. Later in the 19th century the art director Théodore Deck (1823–91) introduced manufacture of siliceous soft-paste pieces. The factory could make large objects that did not crack or split, and that could be decorated in rich colors due to the low firing temperature.[55]

Saint-Cloud soft porcelain spitting bowl

Saint-Cloud soft porcelain spitting bowl Chantilly perforated container

Chantilly perforated container Villeroy Mennecy soft porcelain cock c. 1750

Villeroy Mennecy soft porcelain cock c. 1750 Vincennes, milk jug, 1750–56

Vincennes, milk jug, 1750–56 Sèvres container, 1757–69

Sèvres container, 1757–69

United Kingdom

The first soft paste porcelain manufactured in Britain came from factories in London, soon followed by factories in Staffordshire, Derby and Liverpool. The painter and mezzotintist Thomas Frye (1710–62) produced bone china at his Bow porcelain factory in East London. Bone china was also made at Lowestoft, at first mainly decorated in underglaze blue but later with Chinese-style over-glaze that also included pink and red.[8] Josiah Spode (1733–97), who owned a factory in Stoke-on-Trent from 1776, was a pioneer in use of steam-powered machinery for making pottery. He perfected the process for transfer printing from copper plates.[56] His son, Josiah Spode the younger, began making bone china around the end of the 18th century, adding feldspar to the body. The Spode porcelain was often embossed and decorated in Oriental patterns.[57] The "willow pattern" is thought to have been introduced about 1780 by Thomas Turner of the Caughley Pottery Works in Shropshire. It takes elements from various Chinese designs, including a willow tree, a pair of doves, a pavilion and three figures on a bridge over a lake. Spode and Thomas Minton both manufactured printed blue-and-white pottery with this pattern.[58]

The Worcester Porcelain Company was established in 1751, mainly producing high-quality blue underglaze painted porcelain. At first the decorations were hand painted. Around 1755 the factory introduced overglaze transfer printing, and in 1757–58 introduced underglaze blue transfer printing. Robert Hancock (1730–1817) executed the copper plates and developed the process of transfer printing. Japanese-inspired designs were introduced in the late 1750s.[24] Overglaze hand-painted polychrome decoration was also produced by "the best painters from Chelsea etc.", or by independent decorating shops such as that of James Giles (1718–80). In the 1770s designs were often inspired by the Rococo style of early Sèvres pieces, including exotic birds or flowers on solid or patterned backgrounds. The company introduced a harder paste and harder, brighter glaze after 1796. Between 1804–13 the partner Martin Barr Jr. was responsible for production of superbly painted ornamental vases with landscapes or designs of natural objects such as shells or flowers.[24]

Josiah Wedgwood (1730–95) came from a family of potters. In 1754 he formed a partnership to make earthenware, and became interested in coloring. He invented a rich green glaze for use in leaf and fruit patterns. He established his own pottery in Burslem in 1759, which prospered.[59] His jasper ware has been classed as a fine stoneware, but is similar to porcelain, although the raw materials differ from both. In 1805 his company began to make a hard-paste porcelain in small quantities. Some of this was richly painted in floral designs and gilt.[60] In 1836 John Martin testified before a select committee of the British House of Commons on Arts and Manufactures. He considered that china painting was in decline in his country and no original designs were being produced. He acknowledged that Wedgwood ware, made from the commonest materials, could be beautiful works of art.[61] However, he preferred plain ware to poorly decorated ware.[62]

During the later Victorian era in Britain the Arts and Crafts movement popularized one-of-a-kind, hand-crafted objects. Commercial potteries such as Royal Doulton and Mintons employed young women with artistic talent to create hand-painted or hand-colored art pottery.[63] Until as late as 1939, women in the ceramic industry in Britain were mostly confined to decorating, since they were thought to have special aptitude for repetitive detailed work. The trades' unions did what they could to handicap women even in these occupations, for example refusing to allow them to use hand rests. Often the women were used for subordinate tasks such as filling in outlines or adding decorative sprigs.[64]

Shepherdess and shepherd, Bow porcelain factory, c. 1765–70

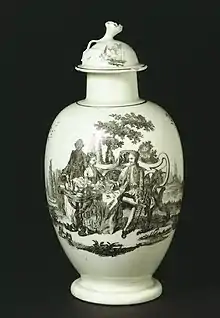

Shepherdess and shepherd, Bow porcelain factory, c. 1765–70 Royal Worcester soft-paste tea canister, transfer-printed in black enamel c. 1768

Royal Worcester soft-paste tea canister, transfer-printed in black enamel c. 1768 Willow pattern plate

Willow pattern plate Wedgwood. Sadness, glazed earthenware c. 1795

Wedgwood. Sadness, glazed earthenware c. 1795 Minton vase, bone china, bleu celeste ground, enamel and gilt c. 1855 (After Sèvres design)

Minton vase, bone china, bleu celeste ground, enamel and gilt c. 1855 (After Sèvres design)_-_DSC06701.JPG.webp) Lambeth Vase, c. 1892, Royal Doulton

Lambeth Vase, c. 1892, Royal Doulton

Other European countries

Porcelain was made in Italy in the 18th century in Venice, in Florence and in the Capodimonte porcelain factory founded in 1743 in Naples by King Charles IV of Naples and Sicily. The latter factory was transferred to Madrid in 1759 when Charles became king of Spain. Modeled figures were often not decorated, or were painted in subdued pastel colors.[65] Porcelain was manufactured in Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands and Russia. The Imperial Porcelain Factory at Saint Petersburg made soft- and hard-paste porcelain, and flourished under Catherine the Great. It featured neoclassical designs with dark ground colors and antique-style cameo painting, including reproductions of engravings of Russian peasants. In 1803 the factory was reorganized by Alexander I, who introduced new products such as large vases with elaborate enamel paintings that were often very similar to oil paintings.[66]

Judgement of Paris from Naples porcelain factory, c. 1801

Judgement of Paris from Naples porcelain factory, c. 1801 Shepherd and shepherdess, Sweden, Marieberg

Shepherd and shepherdess, Sweden, Marieberg Lace pattern plate, Rörstrand, Sweden before 1882

Lace pattern plate, Rörstrand, Sweden before 1882 Products of the Russian Imperial Porcelain Factory, 2nd quarter of the 19th century

Products of the Russian Imperial Porcelain Factory, 2nd quarter of the 19th century

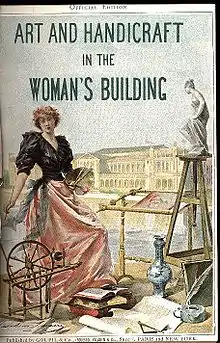

Victorian era amateurs

China painting became a fashionable hobby for wealthy young women in England in the 1870s.[63] This followed the establishment by Mintons of a pottery painting studio in Kensington that provided employment for female graduates of the nearby National Art Training School. Howell & James opened a gallery in Regent Street where they put on annual china painting exhibitions judged by members of the Royal Academy of Arts.[63] China painting also became popular in America. It was acceptable since it resembled other "parlor crafts" such as watercolor and glass painting.[2] At first, men dominated the field of china painting as an artform. Thus Edward Lycett, who had learned his art in the Stoke-on-Trent potteries of England, moved to America where, "the only place where painting of the finer kind was being done as a regular business was at Mt. Lycett's wareroom; and here many ladies resorted to study the methods employed and the materials required."[68] H.C. Standage wrote in Letts's Household Magazine in 1884,

In the household china-painting affords amusement for the girls in the family during the hours their brothers and father leave for business, and return in the evening. To many such ladies, who have nothing better to do than novel reading, this method of filling their time will be esteemed a great boon. Doubly so, since their work may be used either as decorations to the wall surface, if it be plaques they paint, or else disposed of at a profit to themselves to increase their pin-money, or may be given to some bazaar for charitable purposes.[5]

For the duration of the china painting craze, between about 1880 and 1920, many books on pottery making, focusing on painting, were published for the amateur in England and America, for example, A Handbook to the Practice of Pottery Painting by John Charles Lewis Sparkes, Headmaster of the National Art Training School and director of the Lambeth School of Art.[69] Sparkes mentioned the tin-enamel of the Moors and of Gubbio and lustre ware (not the province of the amateur) and the work of William De Morgan. His book, published by a supplier of artists' materials, carried many adverts for colours and pottery blanks, brushes and teachers of pottery painting.

Wheeler's Society of Decorative Art in New York taught pupils to paint simple floral motifs on ceramic tableware. The more talented and experienced china painters could move on to painting portrait plaques.[70] Some women were able to develop professional careers as independent china painters.[63] Rosina Emmet (1854–1948), sister of Lydia Field Emmet, became well known for her ceramic portrait plaques, with characteristic Aesthetic-style treatment. The portraits were either made from the live sitter or from a photograph. One portrait of a young girl that has survived was painted on a white glazed earthenware blank from Josiah Wedgwood & Sons. It is finely detailed, from the background of patterned wallpaper to the details of lacework and individual strands of hair, giving a realistic effect in the English tradition.[71]

Porcelain factories in France, Germany, England and the United States produced plates, bowls, cups and other objects for decoration by china painters.[63] In 1877 McLaughlin recommended the hard French porcelain blanks.[72] The "blanks" were plain white, with a clear glaze, and could be fired several times. Their price varied depending on size and complexity of the object's molding, ranging from a few cents to several dollars. The china painter could buy commercially produced powdered colors of mineral oxides mixed with a low-temperature flux.[63] Some manufacturers sold paints pre-mixed with oil.[73]

In her 1877 A Practical Manual for the use of Amateurs in the Decoration of Hard Porcelain, the American Mary Louise McLaughlin dismissed the preconception that several firings were needed when the work included a variety of colors. She admitted that this could be desirable in porcelain factories, but it would not be practical for amateurs.[74] McLaughlin always prepared her work for a single firing, using a technique similar to watercolors to finish the painting. At that time an amateur could obtain a small muffle furnace that could be used for small pieces.[75] However, she recommended having the firing done by a professional, which would probably be safer, faster and cheaper.[76] Often the amateur artist could take their work for firing to the same shop where they bought their colors and blanks.[77]

In 1887 the ceramic artist Luetta Elmina Braumuller of Monson, Massachusetts launched The China Decorator, A Monthly Journal Devoted Exclusively to this Art. The magazine found a ready market, with many subscribers in the US, Europe and other countries. It became recognized as the authority on all aspects of china painting, and continued to be published until 1901.[78] An 1891 editorial in The China Decorator lamented the number of unqualified teachers who had failed to spend the six months or a year needed for a thorough artist to acquire reasonable knowledge of china painting techniques. The writer estimated that among the tens of thousands of professional and amateur china painters in the US there were at most 500 competent decorators.[79]

China decoration by amateurs was popular in America between about 1860 and 1920. As the practice declined, the artists were encouraged to make their own designs and to learn to throw pots. Those who succeeded were among America's first studio potters.[80]

Evolving styles and attitudes

Overglaze decorations of earthenware, Faience or porcelain were traditionally made with carefully outlined designs that were then colored in. Later designs represented flowers, landscapes or portraits with little overpainting or blending of the colors. In the 20th century china painting techniques became more like oil painting, with blended colors and designs in which attention to light gives three-dimensional effects. More recently a style more like watercolor painting has become more common.[21]

For many years china painting was categorized as a craft, but in the 1970s feminist artists such as Judy Chicago restored it to the status of fine art.[81] In 1979 Chicago wrote,

During a trip up the northwest coast in the summer of 1971, I stumbled onto a small antique shop in Oregon and went in. There, in a locked cabinet, sitting on velvet, was a beautiful hand-painted plate. The shopkeeper took it out of the case, and I stared at the gentle color fades and soft hues of the roses, which seemed to be part of the porcelain on which they were painted. I became enormously curious as to how it had been done. The next year I went to Europe for the first time and found myself almost more interested in cases of painted porcelain than in the endless rows of paintings hanging on musty museum walls.[82]

Chicago spent a year and a half studying china painting. She became intrigued by the effort that amateur women had put into the undervalued art form. She wrote, "The china-painting world, and the household objects the women painted, seemed to be a perfect metaphor for women's domestic and trivialized circumstances. It was an excruciating experience to watch enormously gifted women squander their creative talents on teacups."[83] Chicago was criticized by other feminists for her condescending views on "women's crafts." One wrote that "Chicago the feminist wants to give the china painters their historic due. Chicago the artist is offended by the aesthetic of what they have done."[84]

Noted china painters

- Thomas Baxter (1782–1821), English porcelain painter, watercolor painter and illustrator

- William Billingsley (1758–1828), English ceramic artist, gilder and potter. His technique of painting gave rise to the 'Billingsley Rose'.

- Franz Bischoff (1864–1929), American artist known primarily for his beautiful China painting, floral paintings and California landscapes.

- Judy Chicago (born 1939), American feminist artist and writer

- Philipp Christfeld (c. 1796–1874), German porcelain painter.

- Susan Stuart Frackelton (1848–1932), American painter, specializing in painting ceramics.

- Louis Gerverot (1747–1829), French porcelain painter and businessman

- Lynda Ghazzali (born in Sarawak, Malaysia), entrepreneur and porcelain painter

- James Giles (1718–1780), a decorator of Worcester, Derby, Bow and Chelsea porcelain and also glass

- Gitta Gyenes (1888–1960), Hungarian painter known for early innovations in Hungarian porcelain painting

- Alice Mary Hagen (1872–1972), Canadian ceramic artist from Halifax, Nova Scotia

- John Haslem (1808–84), English china and enamel painter, and writer

- Samuel Keys (1750–1881), English china painter at Royal Crown Derby and Minton

- Mary Louise McLaughlin (1847–1939), American ceramic painter and studio potter

- Jean-Louis Morin (1732–87), French porcelain painter who worked at Sèvres

- Clara Chipman Newton (1848–1936), American artist best known as a china painter

- Henrietta Barclay Paist (1870–1930), American artist, designer, teacher, and author

- Thomas Pardoe (1770–1823), British enameler noted for flower painting

- Josef Karl Rädler (1844–1917), a porcelain painter from Austria

- Adelaïde Alsop Robineau (1865–1929), American painter, potter and ceramist

- John Stinton (1854–1956), British 'Royal Worcester' painter best known for his 'Highland Cattle' scenes

- Maria Longworth Nichols Storer (1849–1932), founder of Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati, Ohio

- Louis Jean Thévenet (1705– c. 1778), French porcelain painter active from 1741 to 1777

- Johann Eleazar Zeissig (1737–1806), German genre, portrait and porcelain painter, and engraver

References

- This article follows the Library of Congress in using the term "China painting" in preference to "porcelain painting", although "porcelain" is preferred to "china" for the material being painted.[1] The term "china painting" is sometimes used to refer only to overglaze painting, in contrast to underglaze decoration.[2] This article uses the term in the broad sense of painted decoration of ceramics, either overglaze or underglaze.

- The word "porcelain" comes from the French porcelaine, which in turns comes from the Italian porcellana, meaning cowrie shell. The material resembles the shell in its glossy surface.[3]

- The Swiss artist Jean-Étienne Liotard tried to obtain backing to manufacture painted porcelain in Vienna in 1777. He failed, but later became known for his still-life paintings of porcelain objects.[67]

- Library of Congress 2006, p. 1310.

- Davis 2007, p. 30.

- Cooper 2000, p. 160.

- Charles 2011, p. 16–18.

- Standage 1884, p. 218.

- Charles 2011, p. 36–38.

- Cooper 2000, p. 161.

- Cooper 2000, p. 174.

- Copeland 1998, p. 4.

- Copeland 1998, p. 28.

- Fraser 2000, p. 94.

- Fraser 2000, p. 95.

- Miller 1885, p. 137.

- Lewis 1883, p. 5–6.

- Osborne 1975, pp. 130–131, 133.

- Standage 1884, p. 219.

- Miller 1885, p. 138.

- Blattenberger 2014, p. 2.

- Miller 1885, p. 41.

- Miller 1885, p. 40.

- Patterson 2014.

- Scott 2002, p. 28.

- Petrie 2006, p. 14.

- Lippert 1987, p. 173.

- Scott 2002, p. 27.

- Scott 2002, p. 24.

- Scott 2002, pp. 27–28.

- Charles 2011, p. 44–46.

- Le Corbeiller 1974, p. 5.

- Doherty 2002, p. 9.

- Doherty 2002, p. 10.

- Valenstein 1998, p. 89.

- Valenstein 1998, p. 92.

- Doherty 2002, p. 11.

- Doherty 2002, p. 13.

- Doherty 2002, p. 14.

- Charles 2011, pp. 8–10.

- Kessler 2012, p. 339.

- Zheng 1984, p. 90.

- Zheng 1984, p. 92.

- Canby 2009, pp. 120–121.

- Twitchett & Mote 1998, p. 379.

- Le Corbeiller 1974, p. 2.

- Le Corbeiller 1974, p. 2–3.

- Le Corbeiller 1974, p. 3.

- Le Corbeiller 1974, p. 4.

- Le Corbeiller 1974, p. 7.

- Le Corbeiller 1974, p. 9.

- Lippincott 1985, p. 121.

- Cooper 2000, p. 163.

- Cooper 2000, p. 164.

- Cooper 2000, p. 165.

- Cooper 2000, p. 166.

- Cooper 2000, p. 167.

- Cooper 2000, p. 169.

- Fleisher 2013, p. 272.

- Church 1886, p. 79.

- Cooper 2000, p. 238.

- Prime 1879, p. 321.

- Church 1886, p. 80.

- Martin 1836, p. 109.

- Martin 1836, p. 110.

- China Painting, Canadian Museum of History.

- Davis 2007, p. 32.

- Cooper 2000, p. 171.

- Cooper 2000, p. 173.

- Lippincott 1985, p. 122.

- Davis 2007, p. 31.

- Sparkes 1879.

- Peck & Irish 2001, p. 181.

- Peck & Irish 2001, p. 180.

- McLaughlin 1877, p. 14.

- Lewis 1883, p. 7.

- McLaughlin 1877, p. 9.

- McLaughlin 1877, p. 10.

- McLaughlin 1877, p. 11.

- Standage 1884, p. 220.

- Luetta E. Braumuller, The China Decorator Reading Room.

- The China Decorator January 1891, p. 120.

- Davis 2007, p. 29.

- Stiles & Selz 1996, p. 291.

- Stiles & Selz 1996, p. 358.

- Gerhard 2013, p. 80.

- Gerhard 2013, p. 226.

Sources

- Blattenberger, Marci (2014), A Beginner's Lesson in China Painting, retrieved 2014-11-26

- Canby, Sheila R., ed. (2009), Shah ʻAbbas: The Remaking of Iran, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-2452-0

- Charles, Victoria (2011-07-01), Chinese Porcelain, Parkstone International, ISBN 978-1-78042-206-0, retrieved 2014-11-28

- China Painting, Canadian Museum of History, retrieved 2014-11-26

- Church, Arthur Herbert (1886), English Porcelain: A Handbook to the China Made in England During the Eighteenth Century as Illustrated by Specimens Chiefly in the National Collections, Committee of Council on Education, retrieved 2014-12-01

- Cooper, Emmanuel (2000). Ten Thousand Years of Pottery. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3554-8. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- Copeland, Robert (1998). Spode. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7478-0364-5. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- Davis, Emily Elizabeth (2007). The Pottery Notebook of Maude Robinson: A Woman's Contribution to Art Pottery Manufacture, 1903--1909. ISBN 978-0-549-18371-6. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- Doherty, Jack (2002-05-30). Porcelain. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1827-2. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Fleisher, Noah (2013-03-29). Warman's Antiques & Collectibles 2014. Krause Publications. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-4402-3462-0. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- Fraser, Harry (2000-10-20). The Electric Kiln. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1758-6. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- Gerhard, Jane F. (2013-06-01). The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the Power of Popular Feminism, 1970-2007. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-4457-7. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- Kessler, Adam T. (2012-07-25). Song Blue and White Porcelain on the Silk Road. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-23127-6. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Le Corbeiller, Clare (1974-01-01). China Trade Porcelain: Patterns of Exchange: Additions to the Helena Woolworth McCann Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-089-2. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- Lewis, Florence (1883). China painting. Cassell. p. 5. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- Library of Congress (2006). "China painting". Library of Congress Subject Headings. Library of Congress. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- Lippert, Catherine Beth (1987). Eighteenth-century English Porcelain in the Collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Indianapolis Museum of Art. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-936260-11-4. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- Lippincott, Louise (1985-01-01). "Liotard's "China Painting"". The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal: Volume 13, 1985. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-090-1. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- "Luetta E. Braumuller". The China Decorator Reading Room. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- Martin, John (1836). "Select Committee of the House of Commons on Arts and Manufactures". The Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette. M. Salmon. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- McLaughlin, Mary Louise (1877). China Painting: A Practical Manual for the Use of Amateurs in the Decoration of Hard Porcelain. R. Clarke. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- Miller, Fred (1885). Pottery-painting. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- Osborne, Harold, ed. (1975), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198661134

- Patterson, Gene (2014). "Oils and Mediums". Porcelain Painters International Online. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- Peck, Amelia; Irish, Carol (2001-01-01). Candace Wheeler: The Art and Enterprise of American Design, 1875-1900. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-002-8. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- Petrie, Kevin (2006-01-25). Glass and Print. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-8122-1946-3. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- Prime, William Cowper (1879). Pottery and Porcelain of All Times and Nations. Harper & Brothers. p. 321. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- Scott, Paul (2002-02-05). Ceramics and Print. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1800-0. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Sparkes, John C. L. (1879), A Handbook to the Practice of Pottery Painting, London: Lechertier, Barbe and Co

- Standage, H.C. (1884). "Simple Directions for Painting on China". Letts's illustrated household magazine. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- Stiles, Kristine; Selz, Peter Howard (1996). Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings. University of California Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-520-20251-1. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- The China Decorator. China decorating publishing Company. 1891. Retrieved 2014-11-26.

- Twitchett, Denis C.; Mote, Frederick W. (1998-01-28). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24333-9. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Valenstein, S. (1998), A handbook of Chinese ceramics, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 9780870995149, retrieved 2016-09-17

- Zheng, Dekun (1984-01-01). Studies in Chinese Ceramics. Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-962-201-308-7. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

.jpg.webp)