Jesuit missions in China

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China is part of the history of relations between China and the Western world. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, between the 16th and 17th century played a significant role in continuing the transmission of knowledge, science, and culture between China and the West, and influenced Christian culture in Chinese society today.

_%22Frontispicio%22_(22629197626).jpg.webp)

The first attempt by the Jesuits to reach China was made in 1552 by St. Francis Xavier, Navarrese priest and missionary and founding member of the Society of Jesus. Xavier never reached the mainland, dying after only a year on the Chinese island of Shangchuan. Three decades later, in 1582, Jesuits once again initiated mission work in China, led by several figures including the Italian Matteo Ricci, introducing Western science, mathematics, astronomy, and visual arts to the Chinese imperial court, and carrying on significant inter-cultural and philosophical dialogue with Chinese scholars, particularly with representatives of Confucianism. At the time of their peak influence, members of the Jesuit delegation were considered some of the emperor's most valued and trusted advisors, holding prestigious posts in the imperial government. Many Chinese, including former Confucian scholars, adopted Christianity and became priests and members of the Society of Jesus.

According to research by David E. Mungello, from 1552 (i.e., the death of St. Francis Xavier) to 1800, a total of 920 Jesuits participated in the China mission, of whom 314 were Portuguese, and 130 were French.[2] In 1844 China may have had 240,000 Roman Catholics, but this number grew rapidly, and in 1901 the figure reached 720,490.[3] Many Jesuit priests, both Western-born and Chinese, are buried in the cemetery located in what is now the School of the Beijing Municipal Committee.[4]

Jesuits in China

The arrival of Jesuits

Contacts between Europe and the East already dated back hundreds of years, especially between the Papacy and the Mongol Empire in the 13th century. Numerous traders – most famously Marco Polo – had traveled between eastern and western Eurasia. Christianity was not new to the Mongols, as many had practiced Christianity of the Church of the East since the 7th century (see Christianity among the Mongols). However, the overthrow of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty by the Ming dynasty in 1368 resulted in a strong assimilatory pressure on China's Muslim, Jewish, and Christian communities, and non-Han influences were forced out of China. By the 16th century, there is no reliable information about any practicing Christians remaining in China.

Fairly soon after the establishment of the direct European maritime contact with China (1513) and the creation of the Society of Jesus (1540), at least some Chinese became involved with the Jesuit effort. As early as 1546, two Chinese boys enrolled in the Jesuits' St. Paul's College in Goa, the capital of Portuguese India. One of these two Christian Chinese, known as Antonio, accompanied St. Francis Xavier, a co-founder of the Society of Jesus, when he decided to start missionary work in China. However, Xavier failed to find a way to enter the Chinese mainland, and died in 1552 on Shangchuan island off the coast of Guangdong,[5] the only place in China where Europeans were allowed to stay at the time, albeit only for seasonal trade.

A few years after Xavier's death, the Portuguese were allowed to establish Macau, a semi-permanent settlement on the mainland which was about 100 km closer to the Pearl River Delta than Shangchuan Island. A number of Jesuits visited the place (as well as the main Chinese port in the region, Guangzhou) on occasion, and in 1563 the Order permanently established its settlement in the small Portuguese colony. However, the early Macau Jesuits did not learn Chinese, and their missionary work could reach only the very small number of Chinese people in Macau who spoke Portuguese.[6]

A new regional manager ("Visitor") of the order, Alessandro Valignano, on his visit to Macau in 1578–1579 realized that Jesuits would not get far in China without a sound grounding in the language and culture of the country. He founded St. Paul Jesuit College (Macau) and requested the Order's superiors in Goa to send a suitably talented person to Macau to start the study of Chinese. Accordingly, in 1579 the Italian Michele Ruggieri (1543–1607) was sent to Macau, and in 1582 he was joined at his task by another Italian, Matteo Ricci (1552–1610).[6] Early efforts were aided by donations made by elites, and especially wealthy widows from Europe as well Asia. Women such as Isabel Reigota in Macau, Mercia Roiz in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Candida Xu in China, all donated significant amounts towards establishing missions in China as well as to other Asian states from China.[7]

Ricci's policy of accommodation

Both Ricci and Ruggieri were determined to adapt to the religious qualities of the Chinese: Ruggieri to the common people, in whom Buddhist and Taoist elements predominated, and Ricci to the educated classes, where Confucianism prevailed. Ricci, who arrived at the age of 30 and spent the rest of his life in China, wrote to the Jesuit houses in Europe and called for priests – men who would not only be "good", but also "men of talent, since we are dealing here with a people both intelligent and learned."[8] The Spaniard Diego de Pantoja and the Italian Sabatino de Ursis were some of these talented men who joined Ricci in his venture.

The Jesuits saw China as equally sophisticated and generally treated China as equals with Europeans in both theory and practice.[9] This Jesuit perspective influenced Leibniz in his cosmopolitan view of China as an equal civilisation with whom scientific exchanges was desirable.[10]

Just as Ricci spent his life in China, others of his followers did the same. This level of commitment was necessitated by logistical reasons: Travel from Europe to China took many months, sometimes years; and learning the country's language and culture was even more time-consuming. When a Jesuit from China did travel back to Europe, he typically did it as a representative ("procurator") of the China Mission, entrusted with the task of recruiting more Jesuit priests to come to China, ensuring continued support for the Mission from the Church's central authorities, and creating favorable publicity for the Mission and its policies by publishing both scholarly and popular literature about China and Jesuits.[11] One time the Chongzhen Emperor was nearly converted to Christianity and broke his idols.[12]

Dynastic change

The fall of the Ming dynasty and the rise of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty brought some difficult years for the Jesuits in China. While some Jesuit fathers managed to impress Qing commanders with a display of western science or ecclesiastical finery and to be politely invited to join the new order (as did Johann Adam Schall von Bell in Beijing in 1644, or Martino Martini in Wenzhou ca. 1645–46),[13] others endured imprisonment and privations, as did Lodovico Buglio and Gabriel de Magalhães in Sichuan in 1647–48[14][15] (see Catholic Church in Sichuan), or Alvaro Semedo in Canton in 1649. Later, Johann Grueber was in Beijing between 1656 and 1661.

During the several years of war between the Qing and the Southern Ming dynasties, it was not uncommon for some Jesuits to find themselves on different sides of the front lines: while Adam Schall was an important counselor of the Qing Shunzhi Emperor in Beijing, Michał Boym travelled from the jungles of south-western China to Rome, carrying the plea of help from the court of the Yongli Emperor of the Southern Ming, and returned with the Pope's response that promised prayer, after some military assistance from Macau.[16][17][18] There were many Christians in the court of the polygamist emperor.

French Jesuits

In 1685, the French king Louis XIV sent a mission of five Jesuit "mathematicians" to China in an attempt to break the Portuguese predominance: Jean de Fontaney (1643–1710), Joachim Bouvet (1656–1730), Jean-François Gerbillon (1654–1707), Louis Le Comte (1655–1728) and Claude de Visdelou (1656–1737).[19]

French Jesuits played a crucial role in disseminating accurate information about China in Europe.[20] A part of the French Jesuit mission in China lingered on for several years after the suppression of the Society of Jesus until it was taken over by a group of Lazarists in 1785.[21]

Travel of Chinese Christians to Europe

Prior to the Jesuits, there had already been Chinese pilgrims who had made the journey westward, with two notable examples being Rabban bar Sauma and his younger companion, who became Patriarch Mar Yaballaha III, in the 13th century.

While few 17th-century Jesuits returned from China to Europe, it was not uncommon for those who did to be accompanied by young Chinese Christians. Alexandre de Rhodes brought Emmanuel Zheng Manuo to Rome in 1651. Emmanuel studied in Europe and later became the first Chinese Jesuit priest.[22] Andreas Zheng (郑安德勒; Wade-Giles: Cheng An-te-lo) was sent to Rome by the Yongli court along with Michał Boym in the late 1650s. Zheng and Boym stayed in Venice and Rome in 1652–55. Zheng worked with Boym on the transcription and translation of the Xi'an Stele, and returned to Asia with Boym, whom he buried when the Jesuit died near the Vietnam-China border.[23] A few years later, another Chinese traveller who was called Matthaeus Sina in Latin (not positively identified, but possibly the person who traveled from China to Europe overland with Johann Grueber) also worked on the same Church of the East inscription. The result of their work was published by Athanasius Kircher in 1667 in the China Illustrata, and was the first significant Chinese text ever published in Europe.[24]

Better known is the European trip of Shen Fo-tsung in 1684–1685, who was presented to king Louis XIV on September 15, 1684, and also met with king James II,[25] becoming the first recorded instance of a Chinese man visiting Britain.[26] The king was so delighted by this visit that he had his portrait made hung in his own bedroom.[26] Later, another Chinese Jesuit Arcadio Huang would also visit France, and was an early pioneer in the teaching of the Chinese language in France, in 1715.

Scientific exchange

Telling China about Europe

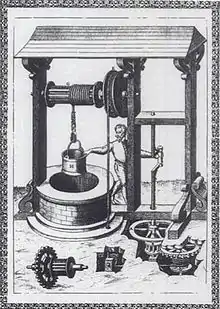

The Jesuits introduced to China Western science and mathematics which was undergoing its own revolution. "Jesuits were accepted in late Ming court circles as foreign literati, regarded as impressive especially for their knowledge of astronomy, calendar-making, mathematics, hydraulics, and geography."[27] In 1627, the Jesuit Johann Schreck produced the first book to present Western mechanical knowledge to a Chinese audience, Diagrams and explanations of the wonderful machines of the Far West.[28] This influence worked in both directions:

[The Jesuits] made efforts to translate western mathematical and astronomical works into Chinese and aroused the interest of Chinese scholars in these sciences. They made very extensive astronomical observation and carried out the first modern cartographic work in China. They also learned to appreciate the scientific achievements of this ancient culture and made them known in Europe. Through their correspondence European scientists first learned about the Chinese science and culture.[29]

Jan Mikołaj Smogulecki (1610–1656) is credited with introducing logarithms to China, while Sabatino de Ursis (1575–1620) worked with Matteo Ricci on the Chinese translation of Euclid's Elements, published books in Chinese on Western hydraulics, and by predicting an eclipse which Chinese astronomers had not anticipated, opened the door to the reworking of the Chinese calendar using Western calculation techniques.

This influence spread to Korea as well, with João Rodrigues providing the Korean mandarin Jeong Duwon astronomical, mathematical, and religious works in the early 1630s, which he carried back to Seoul from Dengzhou and Beijing, prompting local controversy and discussion decades before the first foreign scholars were permitted to enter the country. Like the Chinese, the Koreans were most interested in practical technology with martial applications (such as Rodrigues's telescope) and the possibility of improving the calendar, with its associated religious festivals.

Johann Adam Schall (1591–1666), a German Jesuit missionary to China, organized successful missionary work and became the trusted counselor of the Shunzhi Emperor of the Qing Dynasty. He was created a mandarin and held an important post in connection with the mathematical school, contributing to astronomical studies and the development of the Chinese calendar. Thanks to Schall, the motions of both the sun and moon began to be calculated with sinusoids in the 1645 Shíxiàn calendar (時憲書, Book of the Conformity of Time). His position enabled him to procure from the emperor permission for the Jesuits to build churches and to preach throughout the country. The Shunzhi Emperor, however, died in 1661, and Schall's circumstances at once changed. He was imprisoned and condemned to death by slow slicing. After an earthquake and the dowager's objection, the sentence was not carried out, but he died after his release owing to the privations he had endured. A collection of his manuscripts remains and was deposited in the Vatican Library. After he and Ferdinand Verbiest won the tests against Chinese and Islamic calendar scholars, the court adapted the western calendar only.[30][31]

The Jesuits also endeavoured to build churches and demonstrate Western architectural styles. In 1605, they established the Nantang (Southern) Church and in 1655 the Dongtang (Eastern) Church. In 1703 they established the Beitang (Northern) Church near Zhongnanhai (opposite the former Beijing Library), on land given to the Jesuits by the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing Dynasty in 1694, following his recovery from illness thanks to medical expertise of Fathers Jean-François Gerbillon and Joachim Bouvet.[32]

Latin spoken by the Jesuits was used to mediate between the Qing and Russia.[33] A Latin copy of the Treaty of Nerchinsk was written by Jesuits. Latin was one of the things which were taught by the Jesuits.[34][35] A school was established by them for this purpose.[36][37] A diplomatic delegation found a local who composed a letter in fluent Latin.[38][39]

Telling Europe about China

The Jesuits were also very active in transmitting Chinese knowledge to Europe, such as translating Confucius's works into European languages. Several historians have highlighted the impact that Jesuit accounts of Chinese knowledge had on European scholarly debates in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[40][41][42][43][44]

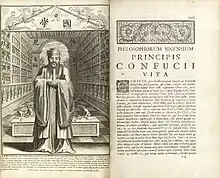

Ricci in his De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas had already started to report on the thoughts of Confucius; he (and, earlier, Michele Ruggieri) made attempts at translating the Four Books, the standard introduction into the Confucian canon. The work on the Confucian classics by several generations of Jesuits culminated with Fathers Philippe Couplet, Prospero Intorcetta, Christian Herdtrich, and François de Rougemont publishing Confucius Sinarum Philosophus ("Confucius, the Philosopher of the Chinese") in Paris in 1687. The book contained an annotated Latin translation of three of the Four Books and a biography of Confucius.[45] It is thought that such works had considerable importance on European thinkers of the period, particularly those who were interested in the integration of the Confucian system of morality into Christianity.[45][46]

Since the mid-17th century, detailed Jesuit accounts of the Eight trigrams and the Yin/Yang principles[47] appeared in Europe, quickly drawing the attention of European philosophers such as Leibniz.

.jpg.webp)

Chinese linguistics, sciences, and technologies were also reported to the West by Jesuits. Polish Michal Boym authored the first published Chinese dictionaries for European languages, both of which were published posthumously: the first, a Chinese–Latin dictionary, was published in 1667, and the second, a Chinese–French dictionary, was published in 1670. The Portuguese Jesuit João Rodrigues, previously the personal translator of the Japanese leaders Hideyoshi Toyotomi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, published a terser and clearer edition of his Japanese grammar from Macao in 1620. The French Jesuit Joseph-Marie Amiot wrote a Manchu dictionary Dictionnaire tatare-mantchou-français (Paris, 1789), a work of great value, the language having been previously quite unknown in Europe. He also wrote a 15-volume Memoirs regarding the history, sciences, and art of the Chinese, published in Paris in 1776–1791 (Mémoires concernant l'histoire, les sciences et les arts des Chinois, 15 volumes, Paris, 1776–1791). His Vie de Confucius, the twelfth volume of that collection, was more complete and accurate than any predecessors.

Rodrigues and other Jesuits also began compiling geographical information about the Chinese Empire. In the early years of the 18th century, Jesuit cartographers travelled throughout the country, performing astronomical observations to verify or determine the latitude and longitude relative to Beijing of various locations, then drew maps based on their findings. Their work was summarized in a four-volume Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique et physique de l'empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie chinoise published by Jean-Baptiste Du Halde in Paris in 1735, and on a map compiled by Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville (published 1734).[48]

To disseminate information about devotional, educational and scientific subjects, several missions in China established printing presses: for example, the Imprimerie de la Mission Catholique (Sienhsien), established in 1874.

Chinese Rites controversy

In the early 18th century, a dispute within the Catholic Church arose over whether Chinese folk religion rituals and offerings to the emperor constituted paganism or idolatry. This tension led to what became known as the "Rites Controversy," a bitter struggle that broke out after Ricci's death and lasted for over a hundred years.

At first the focal point of dissension was the Jesuit contention that the ceremonial rites of Confucianism and ancestor veneration were primarily social and political in nature and could be practiced by converts. Spanish Dominicans and Franciscans, however, charged that the practices were idolatrous, meaning that all acts of respect to the sage and one's ancestors were nothing less than the worship of demons. Eventually they persuaded Pope Clement XI that the Jesuits were making dangerous accommodations to Chinese sensibilities. In 1704 Rome decided against the ancient use of the words Shang Di (supreme emperor) and Tian (heaven) for God, and forbade the practice of sacrifices to Confucius and ancestors. Rome's decision was taken by the papal legate to the Kangxi Emperor, who rejected the decision and required missionaries to declare their adherence to "the rules of Matteo Ricci". In 1724, the Yongzheng Emperor expelled all missionaries who failed to support the Jesuit position.[49]

Among the last Jesuits to work at the Chinese court were Louis Antoine de Poirot (1735–1813) and Giuseppe Panzi (1734-before 1812) who worked for the Qianlong Emperor as painters and translators.[50][51] From the 19th century, the role of the Jesuits in China was largely taken over by the Paris Foreign Missions Society.

See also

Left image: a description of a windlass well, in Agostino Ramelli, 1588.

Right image: Description of a windlass well, in Diagrams and explanations of the wonderful machines of the Far West, 1627.

- Protestant missions in China

- Ruins of Saint Paul's, Macau

- Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception (Hangzhou)

- China and the Christian Impact, translation of Jacques Gernet's Chine et christianisme of 1982

- Cornelius Wessels

- Figurism

- China–France relations

- History of the Jews in China

- List of Catholic missionaries to China

- Medical missions in China

- Catholic Church in China

- List of Protestant theological seminaries in China

- Three Pillars of Chinese Catholicism

References

Citations

- Wigal (2000), p. 202.

- Mungello (2005), p. 37. Since Italians, Spaniards, Germans, Belgians, and Poles participated in missions too, the total of 920 probably only counts European Jesuits, and does not include Chinese members of the Society of Jesus.

- Kenneth Scott, Christian Missions in China, p.83.

- Article on the Jesuit cemetery in Beijing by journalist Ron Gluckman

- Ruggieri & Ricci (2001), p. 151

- Ruggieri & Ricci (2001), p. 153

- Zupanov, Ines G. (2019-05-15). The Oxford Handbook of the Jesuits. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-092498-0.

- George H. Dunne, Generation of Giants, p.28

- Georg Wiessala (2014). European Studies in Asia: Contours of a Discipline. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-1136171611.

- Michel Delon (2013). Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Routledge. p. 331. ISBN 978-1135959982.

- Mungello (1989), p. 49.

- "泰山"九莲菩萨"和"智上菩萨"考". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- Mungello (1989), pp. 106–107.

- 清代中叶四川天主教传播方式之认识

- Mungello (1989), p. 91.

- 南明永曆朝廷與天主教

- 中西文化交流与西方早期汉学的兴起

- Mungello (1989), p. 139.

- Eastern Magnificence and European Ingenuity: Clocks of Late Imperial China – Page 182 by Catherine Pagani (2001) Google Books

- Lach, Donald F. (June 1942). "China and the Era of the Enlightenment". The Journal of Modern History. University of Chicago Press. 14 (2): 211. doi:10.1086/236611. JSTOR 1871252. S2CID 144224740.

- "Yearbook of the Society of Jesus 2014" (PDF), Jesuits, p. 14

- Rouleau, Francis A. (1 January 1959). "The First Chinese Priest of the Society of Jesus: Emmanuel de Siqueira, 1633-1673, Cheng-ma-no Wei-hsin 鄭瑪諾維信". Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu. 28: 3–50.

- Mungello (1989), pp. 139–140, 167.

- Mungello (1989), p. 167.

- Keevak (2004), p. 38.

- "BBC - Radio 4 - Chinese in Britain". www.bbc.co.uk.

- Ebrey (1996), p. 212.

- Ricci roundtable Archived 2011-06-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Udías (2003), p. 53; quoted by Woods (2005)

- 第八章 第二次教难前后

- 志二十

- Li (2001), p. 235.

- Peter C Perdue (30 June 2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-0-674-04202-5.

- Susan Naquin (2000). Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400-1900. University of California Press. pp. 577–. ISBN 978-0-520-21991-5.

- Eva Tsoi Hung Hung; Judy Wakabayashi (16 July 2014). Asian Translation Traditions. Routledge. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-1-317-64048-6.

- Frank Kraushaar (2010). Eastwards: Western Views on East Asian Culture. Peter Lang. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-3-0343-0040-7.

- Eric Widmer (1976). The Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Peking During the Eighteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-0-674-78129-0.

- Egor Fedorovich Timkovskii (1827). Travels of the Russian mission through Mongolia to China, with corrections and notes by J. von Klaproth [tr. by H.E. Lloyd]. pp. 29–.

- Egor Fedorovich Timkovskiĭ; Hannibal Evans Lloyd; Julius Heinrich Klaproth; Julius von Klaproth (1827). Travels of the Russian mission through Mongolia to China: and residence in Pekin, in the years 1820-1821. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. pp. 29–.

- Statman, Alexander (2019). "The First Global Turn: Chinese Contributions to Enlightenment World History". Journal of World History. 30 (3): 363–392. doi:10.1353/jwh.2019.0061. S2CID 208811659 – via Project MUSE.

- Wu, Huiyi (2017). "'The Observations We Made in the Indies and in China': The Shaping of the Jesuits' Knowledge of China by Other Parts of the Non-Western World". East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine (46): 47–88. JSTOR 90020957 – via JSTOR.

- Pinot, Virgile (1932). La Chine et la formation de l'esprit philosophique en France (1640-1740) (in French). Paris: Paul Geuthner. ISBN 9780244506667.

- Giovannetti-Singh, Gianamar (March 2022). "Rethinking the Rites Controversy: Kilian Stumpf's Acta Pekinensia and the Historical Dimensions of a Religious Quarrel". Modern Intellectual History. 19 (1): 29–53. doi:10.1017/S1479244320000426. ISSN 1479-2443. S2CID 228824560.

- Cams, Mario (2017). "Blurring the Boundaries: Integrating Techniques of Land Surveying on the Qing's Mongolian Frontier". East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine. 46 (46): 25–46. doi:10.1163/26669323-04601005. ISSN 1562-918X. JSTOR 90020956. S2CID 134980355.

- Parker, John (1978). Windows into China: the Jesuits and their books, 1580–1730. Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston. p. 25. ISBN 0-89073-050-4.

- Hobson, John M. (2013). The Eastern origins of Western civilisation (10. print ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 0-521-54724-5.

- See e.g. Martino Martini's detailed account in Martini Martinii Sinicae historiae decas prima : res a gentis origine ad Christum natum in extrema Asia, sive magno Sinarum imperio gestas complexa, 1659, p. 15 sq.

- Du Halde, Jean-Baptiste (1735). Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique et physique de l'empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie chinoise. Vol. IV. Paris: P.G. Lemercier. There are numerous later editions as well, in French and English

- Tiedemann 2006, pp. 463–464.

- Swerts & De Ridder (2002), p. 18.

- Batalden, Cann & Dean (2004), p. 151.

Bibliography

- Batalden, Stephen K.; Cann, Kathleen; Dean, John (2004). Sowing the word: the cultural impact of the British and foreign Bible society 1804-2004. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix press. ISBN 9781905048083.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge, New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6.

- Keevak, Michael (2004). The pretended Asian: George Psalmanazar's eighteenth-century Formosan hoax. Detroit, Mich: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814331989.

- Li, Shenwen (2001). Stratégies missionnaires des jésuites français en Nouvelle-France et en Chine au XVIIe siècle. Saint-Nicolas (Québec) Paris: les Presses de l'Université Laval l'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7475-1123-5.

- Mungello, David E. (1989). Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1219-0.

- Mungello, David E. (2005). The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-3815-X.

- Ruggieri, Matteo; Ricci, Michele (2001), Witek, John W. (ed.), Dicionário Português-Chinês : 葡漢詞典 (Pu-Han Cidian) : Portuguese-Chinese dictionary, Biblioteca Nacional, pp. 151–157, ISBN 972-565-298-3 (Detailed account of the early years of the mission).

- Swerts, Lorry; De Ridder, Koen (2002). Mon Van Genechten 1903 - 1974, Flemish missionary and Chinese painter: inculturation of Chinese Christian art. Leuven: Leuven University Press. ISBN 9789058672223.

- Tiedemann, R. G. (2006). "Christianity in East Asia". In Brown, Stewart J.; Tackett, Timothy (eds.). Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 7, Enlightenment, Reawakening and Revolution 1660-1815. Cambridge University Press. pp. 451–474. ISBN 978-0-521-81605-2.

- Udías, Agustín (2003). Searching the Heavens and the Earth: The History of Jesuit Observatories. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 9781402011894.

- Wigal, Donald (2000). Historic Maritime Maps. New York: Parkstone Press. ISBN 1-85995-750-1.

- Woods, Thomas (2005). How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Washington, DC: Regenery. ISBN 0-89526-038-7.