Legalism (Chinese philosophy)

Fajia,[4] often referred to as Legalism, is one of six classical schools of thought in Chinese philosophy. The "Fa school of thought" represents several branches of what Feng Youlan called "men of methods"[5]—statesmen or theoreticians often compared in the west with "political realism"—who contributed greatly to the construction of the bureaucratic Chinese empire. Although lacking a recognized founder, the earliest persona of the Fajia may be considered Guan Zhong (720–645 BCE), while Chinese historians commonly regard Li Kui (455–395 BCE) as the first Legalist philosopher. Sinologist Herrlee G. Creel regarded the combination of administrator Shen Buhai (400–337 BCE) and Legalist Shang Yang (390–338 BCE), syncretized under Han Fei (c. 240 BCE), as becoming what would historically be known as the Fajia, with the former two representing its founding branches.[6]

| Legalism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

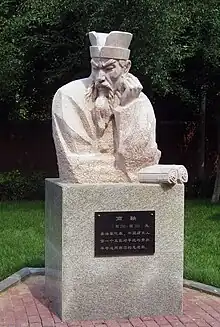

Statue of pivotal reformer Shang Yang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 法家 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | 'way of doing' or 'standard' school of thought[1][2][3]: 59 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Sinologist Jacques Gernet considered the "theorists of the state" later christened Fajia or 'Legalists' to be the most important intellectual tradition of the fourth and third centuries BCE.[7] With the Han dynasty taking over the governmental institutions of the Qin dynasty almost unchanged, the Qin to Tang dynasty were characterized by the "centralizing, statist tendencies" of the Fa tradition. Leon Vandermeersch and Vitaly Rubin would assert not a single state measure throughout Chinese history as having been without Legalist influence.[8]

Dubbed by A. C. Graham the "great synthesizer of 'Legalism'", Han Fei is regarded as their finest writer, if not the greatest statesman in Chinese history (Hu Shi). Often considered the "culminating" or "greatest" of the "Legalist's" texts,[9] the Han Feizi is believed to contain the first commentaries on the Dao De Jing. Sun Tzu's The Art of War incorporates both a Daoist philosophy of inaction and impartiality, and a Legalist system of punishment and rewards, recalling Han Fei's use of the concepts of power (勢, shì) and technique (術, shù).[10] Temporarily coming to overt power as an ideology with the ascension of the Qin dynasty,[11]: 82 the First Emperor of Qin and succeeding emperors often followed the template set by Han Fei.[12]

Though the origins of the Chinese administrative system cannot be traced to any one person, prime minister Shen Buhai may have had more influence than any other in the construction of the merit system, and might be considered its founder, if not valuable as a rare pre-modern example of abstract theory of administration. Creel saw in Shen Buhai the "seeds of the civil service examination", and perhaps the first political scientist.[13]: 94 [14]: 4–5

Concerned largely with administrative and sociopolitical innovation, Shang Yang was a leading reformer of his time.[15][11]: 83 His numerous reforms transformed the peripheral Qin state into a militarily powerful and strongly centralized kingdom. Much of "Legalism" was "the development of certain ideas" that lay behind his reforms, helping lead Qin to ultimate conquest of the other states of China in 221 BCE.[16][17]

Taken as "progressive," the Fajia were "rehabilitated" in the twentieth century, with reformers regarding it as a precedent for their opposition to conservative Confucian forces and religion.[18] As a student, Mao Zedong championed Shang Yang, and towards the end of his life hailed the anti-Confucian legalist policies of the Qin dynasty.[19]

Historical background

The Zhou dynasty was divided between the masses and the hereditary noblemen. The latter were placed to obtain office and political power, owing allegiance to the local prince, who owed allegiance to the Son of Heaven.[20] The dynasty operated according to the principles of Li and punishment. The former was applied only to aristocrats, the latter only to commoners.[21]

The earliest Zhou kings kept a firm personal hand on the government, depending on their personal capacities, personal relations between ruler and minister, and upon military might. The technique of centralized government being so little developed, they deputed authority to regional lords, almost exclusively clansmen. When the Zhou kings could no longer grant new fiefs, their power began to decline, vassals began to identify with their own regions. Aristocratic sublineages became very important, by virtue of their ancestral prestige wielding great power and proving a divisive force. The political structures late Springs-and-Autumns period (770–453 BCE) progressively disintegrated, with schismatic hostility and "debilitating struggles among rival polities."[22]

In the Spring and Autumn period, rulers began to directly appoint state officials to provide advice and management, leading to the decline of inherited privileges and bringing fundamental structural transformations as a result of what may be termed "social engineering from above".[3]: 59 Most Warring States period thinkers tried to accommodate a "changing with the times" paradigm, and each of the schools of thought sought to provide an answer for the attainment of sociopolitical stability.[15]

Confucianism, commonly considered to be China's ruling ethos, was articulated in opposition to the establishment of legal codes, the earliest of which were inscribed on bronze vessels in the sixth century BCE.[23] For the Confucians, the Classics provided the preconditions for knowledge.[24] Orthodox Confucians tended to consider organizational details beneath both minister and ruler, leaving such matters to underlings,[13]: 107 and furthermore wanted ministers to control or at least admonish the ruler.[25]: 359

Concerned with "goodness", the Confucians became the most prominent, followed by the proto-Daoists and the administrative thought that Sima Tan termed the Fajia. But the Daoists focused on the development of inner powers, with little respect for mundane authority[26][27] and both the Daoists and Confucians held a regressive view of history, that the age was a decline from the era of the Zhou kings.[28]

Invention of the Fa School

.jpg.webp)

Along with Daoism the Fajia would only be taken to be a school starting with the Han dynasty historians who created the traditional labels and categorized their thinkers. Han dynasty historiographers Sima Tan and Sima Qian essentially invented the Fa-school in the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji). Intended to represent schools of thought rather than groups of people, Sima Tan does not actually name anyone under it, or for that matter under any of the other schools. Although usually referring to the particular Warring States period philosophers, inclusion among the Fajia is purely ideological and essentially arbitrary.

Less well defined than Confucianism and Mohism, it is unclear when prior to the Han they would have come to be regarded as an intellectual faction. Although one might assume an ancient arcanum, with Guan Zhong (720–645) later included among them, it may not have been considered a coherent ideology until Han Fei, only forming a complex of ideas around the time of Li Si (280–208 BCE), elder advisor to the First Emperor. It was probably never a school in the sense of the Confucians or Mohists, or an organized or self-aware movement at all.

Sima Qians's Historical Records use the term Daojia synonymously with "the Teachings of the Yellow Emperor and Lao-tzu" (Huang-Lao), being Sima Qian's own faction, retroactively applying the term to Shen Dao, Shen Buhai, and Han Fei amongst others. Although for instance the typically Huang-Lao Huainanzi contains elements of both the fajia and proto-Daoism, Sima Qian would not have meant Daoism by the term as it would be understood modernly.

Regardless, texts commonly class Guan Zhong and Shen Dao under Daojia before they are later classed under Fajia. The much later Guanzi, containing proto-Daoist texts, was classed as Daoist in the Han bibliography. The outer Zhuangzi takes Shen Dao as Daoistic, preceding both Lao Tzu and Zhuangzi. While Creel would an suggest influence by Shen Buhai's early thought on the Daodejing, Sinologist Chad Hansen, as regardless authoring the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy's Daoism, would take Daoist theory as beginning in the language relativism of Shen Dao.

Modernly, fa, as representing measurement standards used in the administration, can be seen to be essentially rooted in the logic or "names" discussions of the Mohists and subsequent school of names who used the term. The Daodejing does not suggest direct exposure to the school of names, although it's discussion of "names that cannot be named" place it within the same milieu as a reaction to Mozi. But with formal similarities between the texts and Daoism, along with Huang-Lao and other textual precedent, the theorists were often supposed by the Chinese and early scholarship to have studied and been rooted in Daoism. Modern scholarship does not take Daodejing to be as ancient as its portrayal, but attempts to root the Han Feizi in proto-Daoist attitudes, naturalism or milieu can be still seen within scholarship.

Rather than Sima Qian, the Han History lists Li Kui, Shang Yang, Shen Buhai, Han Fei, Shen Dao, and Han Fei under the School of Fa (Fajia), to which is often added Guan Zhong.

As for Fajia, Sima Qian says:

The fajia are strict and have little kindness, but their alignment of the divisions between lord and subject, superior and inferior, cannot be improved upon. … Fajia do not distinguish between kin and stranger or differentiate between noble and base; all are judged as one by their fa. Thus they sunder the kindnesses of treating one’s kin as kin and honoring the honorable. It is a policy that could be practiced for a time, but not applied for long; thus I say: “they are strict and have little kindness.” But as for honoring rulers and derogating subjects, and clarifying social divisions and offices so that no one is able to overstep them—none of the Hundred Schools could improve upon this.

With the synthesis of Han Fei as precedent, the Records generalize Shang Yang (Gongsun), Shen Buhai and Han Fei as adherents of the doctrine of “performance and title” (xing ming 刑名). The doctrine of Han Fei originating in Shen Buhai, it involves personnel selection through the usage of proposals to establish offices (names), comparing them with results. Han Fei includes Shen Buhai under his own doctrine of Shu (technique) alongside his own advocation of harsh punishments, and the First Emperor lists Xing-Ming amongst his accomplishments.

Quotations from the Shangjunshu demonstrate a Names practice of its own, but although the administration of Gongsun Yang, remembered posthumously for harsh punishments, was otherwise pioneering, he did not practice the administrative method of Shen Buhai. Shen Buhai practiced an less automated version with an earlier name, lacking punishment. For the purpose of scholarship, the term generally represents a primary practice of Han Fei and Shen Buhai as extension, and not an alternative moniker for the Fajia.

Sima Qian names reformers like Jia Yi as an advocate of Shen Buhai and Gongsun, even though Jia Yi wrote the Disquisition Finding Fault with the Qin, and probably was not an advocate of Gongsun. Nonetheless, Jia Yi exiled to the southern Changsha Kingdom under factional pressure, although still tutoring a son of the Emperor. The historiographer Liu Xin (c. 50 BCE – 23 CE), as a kind of follow up work, assigned the schools as having originated in various ancient departments, which was adopted by later Chinese scholars even into the later 1700s. Maintaining a lack of distinction between officers and teachers among the Zhou until its disintegration, it portrays the Fajia as having originated in what Feng Youlan (1948) translates as the Ministry of Justice, emphasizing strictness, reward and punishment. Although considering its social indications as not without merit, Feng Youlan did not accept this theory.

With the Han dynasty shifting favor from Huang-Lao to Confucianism, the orthodox interpretation of the Fajia becomes Confucian and more critical. It would "be quite popular and respectable to oppose the harsh use of penal law"(Creel), and apart from disliking the managerial controls of Xing-Ming itself, those otherwise disliked by the Confucian orthodoxy, with some philosophical association, would also often be slurred as Fajia, like the otherwise Confucianistic reformers Guan Zhong and Xunzi, and the Huang Lao themselves.

Although Sima Qian appeared to be aware of the differences between Shen Buhai and Gongsun, Creel suggests that this would seem to disappear among scholars as early as the Western Han dynasty. Although its proponents were often of the Shen Buhai branch, and Gongsun Hong, who founds the civil service examination, studied Xing-Ming, it becomes known as penal law within the administration. Administrative methods, Shen Buhai moderates and even otherwise Confucians are all slurred as Fajia depending on factional interests, becoming known as such. Han Fei, Gongsun, and Shen Buhai are censured, apart from fragments the work of Shen Buhai disappears from history, and "Legalists" or otherwise more moderate practical administrators are recruited under Confucian syncretism.[29] [30] [31] [32]

Western reception as Realists

As presented by Athur Waley (1939), Realist interpretation of our subject in part represents an early critique of Legalist interpretation. Although Fa is understood modernly to be broader than law and punishment, represented most prominently in the 1928 translation of the Book of Lord Shang, Waley says that "they held that law should replace morality... (but) apart from their reliance on law and punishment, their demands may be summed up in the principle that government must be based upon the actual facts of the world as it now exists. Rejecting all appeals to tradition and supernatural guidance, the term Realist seems to me to fit the general tendency of their beliefs better than school of law."[27]

To the first point, positive moral interpretation is elaborated for the subject modernly. That "government must be based upon the actual facts of the world as it now exists" is reiterated by A.C. Graham (1989) as "These are political philosophers, the first in China to start not from how society ought to be but how it is." To it's point, Graham quotes his relevant contemporary Benjamin I. Schwartz. Contrary to common comparisons of Han Fei with Machiavelli, Schwarz observed that Machiavelli taught an art rather than a science of politics, while the Legalists "seem closer in spirit to certain 19th- and 20th-century social-scientific 'model builders'". Schwarz "finds in China more anticipations of contemporary Western social sciences than of the natural sciences", with Shen Buhai's 'model' of bureaucratic organization "much closer to Weber's modern ideal-type than to any notion of patrimonial bureaucracy."[33]

In the Realist vein, A.C. Graham's "Disputers of the Tao" titled his Legalist chapter "Legalism: an Amoral Science of Statecraft", sketching the fundamentals of an "amoral science" in Chinese thought largely, Sinologist Goldin notes in a criticism, based on the Han Feizi, consisting of "adapting institutions to changing situations and overruling precedent where necessary; concentrating power in the hands of the ruler; and, above all, maintaining control of the factious bureaucracy."[34]: 267 [1]

Eirik Lang Harris of The Shenzi Fragments (2016) echoes the view of "starting not from how society ought to be but how it is" as a commonality between the Fajia's four most prominent figures. Tao Jiang's modern formulation of the Fajia reiterates Graham: With Fa as their key notion, the Fajia hold in common a focus in the institutionalization of political power, and a questioning of the moral values of the Confucians, disputing an assumed connection between personal virtue and political authority. Graham says: "they have common ground in the conviction that good government depends, not as Confucians and Mohists supposed on the moral worth of persons, but on the functioning of sound institutions."

Modernly, Sinologist Yuri Pines still takes the realist principle as a foundation for the tradition. While Legalist interpretation has been criticized modernly, Pines takes Realism as having been defended to be more or less still legitimate, although as with Tao Jiang accepts Legalist interpretation as still having explorative value. Noting them as "generally devoid of overarching moral considerations", or conformity to divine will, Pines terms the members of the Fa tradition as "political realists who sought to attain a 'rich state and a powerful army' (Shang Yang-Han Fei) and to ensure domestic stability", only displaying "considerable philosophical sophistication" when they needed to justify departures from conventional approaches.

Realist interpretation however should be qualified, as Pines does himself. As a matter of discipline, Pines suggests the Fa tradition as a more suitable categorical framing, with Fa itself representing not oppression but as transparency. Pines qualifies against a perception of them as totalitarian, as stated by "not a few scholars", including Feng Youlan (1948), Creel (1953) as prior to some of his more prominent work on Shen Buhai, and Zhengyuan Fu's 1996 The Earliest Totalitarians. Although (the Shang Yang branch's harsh laws) and "rigid control over the populace and the administrative apparatus" might seem to support totalitarianism, apart from exposing the fallacies of their opponents, the Fa tradition has little interest for instance in thought control, and Pines does not take them as "necessarily" providing an ideology of their own.[2][35]

Various modern scholarship

In contrast to what he takes as the "simple behaviourism" of Schwarz and Graham, Hansen takes Han Fei as more sociological. The ruler should not trust people because their calculation is essentially based on their position, regardless of their past relationship. A wife, concubine or minister all have positional interests. Hence, the ruler engages in calculations of benefit rather than relation. Ministers simply interpret moral guidance in ways that benefit their position. The ruler exclusively uses Fa measurement standards for calculation to reduce possible interpretation. The enemy of order and control is simply the enemy of objective standards, draining power by twisting interpretation through consensus evaluation of clique interests.

Ross Terrill's 2003 New Chinese Empire viewed "Chinese Legalism" as "Western as Thomas Hobbes, as modern as Hu Jintao... It speaks the universal and timeless language of law and order. The past does not matter, state power is to be maximized, politics has nothing to do with morality, intellectual endeavour is suspect, violence is indispensable, and little is to be expected from the rank and file except an appreciation of force." He calls Legalism the "iron scaffolding of the Chinese Empire", but emphasizes the marriage between Legalism and Confucianism.

Leadership and management in China (2008) takes the writings of Han Fei as almost purely practical. With the proclaimed goal of a “rich state and powerful army”, they teach the ruler techniques (shu) to survive in a competitive world through administrative reform: strengthening the central government, increasing food production, enforcing military training, or replacing the aristocracy with a bureaucracy. Although typically associated with Shang Yang, Kwang-Kuo Wang takes the enriching of the state and strengthening of the army as dating back to Guan Zhong.

Contrary Graham, Goldin (2011) would not regard Han Fei as trying to work out anything like a general theory of the state, or as always dealing with statecraft. Noting Han Fei as as also often concerned with saving one's hide, including that of the ruler, the Han Feizi also has one chapter offering advice to ministers "contrary to the interests of the ruler, although this is an exception... The fact that Han Fei endorses the calculated pursuit of self-interest, even if it means speaking disingenuously before the king, is not easily reconcilable with the reconcilable with the notion that he was advancing a science of statecraft."

Pines page has taken the goal of a “rich state with powerful army” as a primary subject since 2014. In this vein, Pines takes human nature to be a "second pillar" of fa political philosophy, as eschewing it's discussion. The "overwhelming majority of humans are selfish and covetous", which is not taken to be alterable, but rather "can become an asset to the ruler rather than a threat." In this regard, Han Fei is an addendum to Gongsun Yang, with Shen Dao contributing.

Kenneth Winston emphasizes the welfare espoused by Han Fei, but while Han Fei espoused that his model state would increase the quality of life, Schneider (2018) reviews this as not being considered this a legitimizing factor; rather, a side-effect of good order. He focused on the functioning of the state, the ruler's role as guarantor within it, and aimed in particular at making the state strong and the ruler the strongest person within it.[36]

Legalist interpretation

Varying between interpretation and translational convention, the various Sinologists, particularly older one's like Arthur Waley (1939 Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China), but also more modernly A.C. Graham (1989 Disputers of the Dao), may employ Legalism or Realism in reference to the thinkers the Chinese traditionally termed Fajia; "Realists called in Chinese the Fajia, School of law... we might call Amoralists"(Waley) or "when Sima Tan classified the philosophers under his Six Schools he grouped the teachers of realistic statecraft under a 'School of Law' (Fa chia), for which the current English abbreviation is 'Legalists'"(Graham)". This is not to say that either were not respected major scholars, let alone that Graham has nothing to contribute; in fact, Hansen takes him as theory.

Joseph Needham's (1956) Science and Civilization took the "central conception" of Fa as "positive law", expounded with "great clarity by Gongsun Yang in the Shangjunshu". Arguing against an amoral perception for Han Fei, Kenneth Winston (2005) takes Peerenboom 1993 as Legal positivism's late notable argument, with the clarity and promulgation of Fa as law divorced from morality. Taking them as Legal positivists, amongst other comparisons, Zhengyuan Fu's The Earliest Totalitarians (1996), dedicating a brief mention of Fa to a single page, elaborates more on the amoral than the legal front. The term Legalism still retains some conventional use, for instance in Adventures in Chinese Realism (2022).

With an emphasized commonality between Shang Yang and Han Fei, a critical reference by Goldin for Scott Cook (2005) defines Legalism for the two as a "similar set of tenets concerning the rule of law and strict application of rewards and punishments." In this vein, Goldin takes Graham's Legalism as referring to little more than a realist take on the philosophy of Han Fei, to the guided exclusion of related currents. Although the Guanzi is by extension generally included among the Fajia, it is not generally taken to be a Legalist text, such that Goldin would not be sure who Legalism includes apart from, supposedly, Han Fei.

Haig Patapan (Chinese Legality 2022), in a preamble for comparison with Xijinping, would still suggest a preference by Han Fei for extreme authoritarianism and a legal positivist ruler "unconstrained by conventional, ethical, or legal limitations". Considering Han Fei ambiguous, he doesn't specifically argue the point. Discussing the selection of ministers, and contrasting Han Fei with Confucianism, Han Fei's ruler manages self-interested persons to his own benefit while looking to a "more comprehensive good", including advice not to mistreat the people. Haig takes Fa as law as advancing the general good, aiming at plain comprehension, broad public dissemination, consistency, stability and enforcement, albeit in Han Fei's case advising heavy punishment. Here essentially reiterating Winston with regards Fa as law, to quote Haig, Han Fei says that law (fa) "prevents the strong from attacking the weak, the majority from oppressing the minority, allows the old to live in peace, the young to have a chance to grow, and to secure peaceful borders."

Mohist interpretation

In contrast to its term, even the early scholarship of Feng Youlan (1948) considered it incorrect to associate the thinkers with jurisprudence, describing them as teaching methods of organization and leadership for the governing of large areas. The term Legalist is apparently of unknown origin. Creel saw it to "contrast strangely" with Han Fei blaming Shen Buhai, as the opposite of his doctrine from Shang Yang, for concentrating all of his attention on administrative technique and neglecting law (or more broadly Hansen, the public Fa.) Given its English history, Creel suggested the term may be Franciscan derived as a kind of mutual sympathy, essentially an inaccurate, distorting slur giving "undue prominence" to the harsh penalties of Shang Yang from a time when Shen Buhai had been largely forgotten. Goldin suggests similar religious origins for the English term.

Still considering Legalism to have explorative value, professor Tao Jiang (2021) regards part of Creel's work as the differentiation of Shen Buhai, Fa and the Fajia from Legalist interpretation. Making a study of the Shen Buhai fragments, seeing remarkable similarities between the Han Feizi and the fragments, noting imperial China as never fully accepting the role of law and jurisprudence, taking the managerial Shen Buhai branch as predominantly influential, and seeing the Shangjunshu as also sometimes using Fa administratively, in Creel's opinion, while one might say that the members of the Fajia played a great role in the basic establishment of traditional Chinese government, one cannot say that Legalists did. Moreover, their branches often had different interests historically, with Shen's branch often opposing penal punishment.

With Creel, Schwarz, Graham, Hansen, and Ivanhoe as primary references, amongst other works on the Mohists, the Oxford (2011) presents the term Legalism as having interpreted Fa primarily as law, where anciently it did not specifically represent law. The Oxford roots Fa in the easily applied Standards (Fa) and models of the Mohists, still taking law as a kind, but being conceptually closer to performance standards represented by tools providing shape, weight and length. The Fajia's mention in the Routledge's History of Chinese Philosophy would take Fa with regards law as primarily concerned with weights, measures, width of chariots etc., only derivatively including penal law as "explicit public formulations of punishments mechanically geared to named wrongs."

Benjamin I. Schwartz (1985), with reference to the Mohists, noted the inaccuracy of law in many cases, translating it as model, standard, copy, or imitation, with reference to the carpenter's square, compass and builder's plumb-line. The behavior of Mozi's ruler acts as Fa for the noble's and officials as in Confucianism, moving towards "prescriptive method or techne", describing craft and political technique. In contrast to Hansen, Schwarz still regarded Fa as an alternate means to social control from Li.

A.C. Graham (1989) takes takes particular note of the precedent of the Confucian Mencius, whose Fa, apart from models, exemplars and names, includes such physical characteristics as statistics, scales, volumes, consistencies, weights, sizes, densities, distances, and quantities. Accepting distinctions regarding Shen Buhai, in contrast to Creel and Hansen, Graham still viewed Fa as shifting from persons to be imitated towards impersonal relations of bureaucracy, "contracting" Standards (Fa) towards law as paired with and backed by parallels of reward and punishment as early as 600bc, albeit piecemeal. Outside of logical contexts, Graham notes Fa as representing a "standard or exemplar to be imitated", which is still illustrated geometrically.

Sinologist Chad Hansen locates Legalist interpretation, if applied too broadly, in translation; Chinese characters are held to change meaning more often than words in other languages. The political thought of the Fajia have been said to resemble something like Legal positivism. Those who know Chinese, armed with a dictionary, translate it as law. When any of the others schools use Fa, it refers to measurement standards and exemplars. Han Fei says: "If the ruler has regulations based on Fa (measurement standards) and criteria and apply these to the mass of ministers, then the he cannot be dupped by cunning and fraud." Hansen suggests that laws cannot generally prevent deception. The meaning shared with the other schools can, comparing measurements against standards.[37]

Creel's branches of the Fajia

Sinologist Herrlee G. Creel (1970/1974) presents Han Fei as largely responsible for synthesizing the various tendencies that would be grouped together under what Sima Tan termed the Fajia. These stem primarily from what Creel considered to be two disparate contemporary thinkers, Shang (Gongsun) Yang and Shen Buhai. Han Fei at least portrays himself as combining the two. The combined reference, Creel explains, is what would commonly become known as the Fajia, with continued influence after the fall of the Qin dynasty. Although Han Fei's status as "grand synthesizer" has generally been accepted by scholarship, Creel only considered its combination very imperfect.

Because, historically, despite the presentation of their opponents, those advocating policies derived of Shang Yang or Shen Buhai did not endorse each other's views, Creel advised that the Shen Buhai group be called "administrators", "methodists" or "technocrats". Not without its subsequent categorical dissent, neither Shen Buhai's or his successors, Creel said, can be understood as Legalist by the English definition of the term. Although accepting the branches lens by the time of its writing, Michael Loewe of the Cambridge History of China Volume 1 (1978) has reservations: Han Fei called both branches "the instruments of Kings and Emperors", and Li Si praises them equally, finding no contradiction between them. Mr. Loewe instead argues for their complementarity, with life in the Qin Empire being more reasonable, and government more sophisticated, than if it had been based on the dogma of the Book of Lord Shang (Shangjunshu) alone.

Although discussed elsewhere, Creel's 1974 Shen Pu-Hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B. C. represents the only major publication on Shen Buhai, with Tao Jiang (2021) notably devoting a chapter to him, elsewhere referencing a summation of the material covered here. As a rare example of verbatim usage, S. R. Hsieh's 1995 introductory recap followed Creel to the letter, calling them "Legalists/Administrators", while Karyn Lai's dedicated 2008 Introduction to Chinese Philosophy still relied heavily on Creel and Benjamin Schwarz.

Han Fei himself presents the two schools. Han Fei says, with a more modern translation;[38]

Now Shen Buhai spoke about the need of Shu ("Technique") and Shang Yang practices the use of Fa ("Standards"). What is called Shu is to create posts according to responsibilities, hold actual services accountable according to official titles, exercise the power over life and death, and examine into the abilities of all his ministers; these are the things that the ruler keeps in his own hand. Fa includes mandates and ordinances promulgated to the government offices, penalties that are definite in the mind of the people, rewards that are due to the careful observers of standards, and punishments that are inflicted upon those who violate orders. It is what the subjects and ministers take as a model. If the ruler is without Shu he will be overshadowed; if the subjects and ministers lack Fa they will be insubordinate. Thus, neither can be dispensed with: both are implements of emperors and kings.

Although their topics are not as narrow as Han Fei presents, and despite Han Fei's inclusion of power over life and death under his own Shu, there is no basis to suppose that Shen Buhai advocated Shang Yang's doctrine of reward and punishments. Creel notes six works as identifying Shen with bureaucracy; none identify him with penal law when spoken of by himself, and none pre-Han. Only when he is paired with Shang Yang is penal law attributed to them together in the Han dynasty. Historically, as with Shen himself, Shen's so-called Shu "branch" largely ignored Shang Yang and penal practice and sometimes even opposed punishments. His doctrines, called shu, are described as "concerned almost exclusively" with the ruler's selection of ministers.

In contrast to the limited body pertaining to Shen Buhai, censured under Han dynasty Confucian influence, Creel notes an "impressive body" of early works unanimously testifying Gongsun Yang's doctrines as described by Han Fei. That is, his doctrine being called Fa, as including penal law, rewards and punishments, and lacking Shu, or managerial technique. Apart from general mutual surveillance and holding ministers to the public Fa, he advised no method to control and supervise ministers. Most historical works posthumously emphasize his use of harsh penal law. None indicate concern for organization or control of the bureaucracy. Recalled by Tao Jiang, Creel mostly leaves the Legalist interpretation of him alone, accepting it as the Legalist branch.

However, despite portrayal, the Han dynasty's penal reception, and Duvendak's early primary translation of law, in reviewing the Shangjunshu, Creel also saw Gongsun as sometimes using Fa in an administrative sense, of which Shu is a variety. The Book of Lord Shang, Goldin says, still engages statutes more from an administrative standpoint, as well as addressing many other administrative questions.[1] Pines's 2017 translation of the Book of Lord Shang uses law where appropriate for one half of it's uses, but employs a Shu interpretation in analyzing it's Fa, considering it to have impersonal administration as its second most common meaning after law.

The scholar Shen Dao (350 – c. 275 BCE) covered a "remarkable" quantity of "Legalist" and Daoistic themes, and there was a time speculating a third "branch" (e.g. Feng 1948), but he lacked a recognizable group of followers. Xun Kuang goes as far as to call him "beclouded" by Fa, and Han Fei sidelines him, basing himself more in Shen Buhai's method of administration. He was instead incorporated into the Han Feizi and The Art of War for his themes on Shih, being "power" or "situational advantage". Despite its necessity, and although seeking to improve it's argument, Han Fei says that he speaks on Shih "for mediocre rulers", emphasizing institution. Xunzi references Shen Buhai rather than Shen Dao for the origin of the doctrine of power. Although more theoretical, Han Fei may have otherwise derived shih from the Book of Lord Shang.[39] [40] [41]

Three Elements view

A three elements view of the subject was developed by Liang Qichao through a misinterpretation of Han Fei's critique of Shen Dao's views on power, chapter 40, the “Objection to Positional Power”, leading to a view of Legalist thought as having one primary Legalist current and two deviant sub-currents, being Shen Buhai's principle of rule by techniques (shuzhizhuyi 術治主義), and Shen Dao's “principle of rule by positional power” (shizhizhuyi 勢治主義). The subject's early discussion may be seen as an early modern evidence against the idea that, unlike India, China lacked a tradition to fall back on in modern reform, but its view of the Han Feizi was refuted by Chinese scholars long ago. Although Liang Qichao is occasionally discussed, no one holds the view in the west.

Liang Qichao received little literary attention. Professor Tao Jiang (2021) takes the three elements of Feng Youlan (1948) as a representing a traditional view of the subject, comparing it against Creel's work. Feng Youlan introduced Shih as power or authority, Shu as the method or art of conducting affairs and handling men (statecraft), and Fa as law, regulation or pattern, connecting Fa with Gongsun Yang, Shu with Shen Buhai, and Shih with Shen Dao, with each supposed to have a group preceding Han Fei, the idea being that Han Fei synthesizes them.

Engineering manager Donald V Etz's Han Fei Tzu: Management Pioneer in the 1964 Public Administration Review reiterated Feng Youlan's view of three schools preceding Han Fei. Following Feng Youlan's lead, despite the continued Legalist reception that would follow Creel, Detz would take Han Fei's laws as representing, in more modern terms, regulations, expressing Han Fei's three principles as regulation, delegation, and motivation.

Ellen Marie Chen (1975) says: Han Fei's prince must make use of Fa, surround himself with an aura of wei (majesty) and shi, and make use of the art (shu) of statecraft. The ruler who follows Dao moves away from benevolence and righteousness, and discards reason and ability, subduing the people through Fa. Only an absolute ruler can restore the world, and orderly rule for all “All-under-Heaven” can be attained only under an omnipotent monarch.

Zhengyuan Fu's (1996) The Earliest Totalitarians presented power (shi), law (fa), and statecraft (shu) as the three pillars of Legalism, with Shen Dao emphasizing power, Shang Yang law, Shen Buhai statecraft, and Han Fei their synthesizer. According to reviewer Randall Peenrenboom, by that time the view was considered as overly simplistic; Zhengyuan Fu employed it for the sake of the reader, organizing three chapters with one per theme.

Reviewer Song Hongbing notes Soon-ja Yang's (2010) New Studies of Han Feizi’s Political Thought as not relying on the traditional methodology of the three elements and three philosophers, instead presupposing dao as its highest concept, with Han Fei misunderstanding the concept. Soon-ja Yang compares Confucianism and "Legalism".[42]

Creel's interpretive unity

While Feng Youlan's view assumed the existence of three groups preceding Han Fei, Creel saw however no evidence of a Shen Dao "school". Han Fei criticizes Shen Buhai for lacking Fa, which Creel's earlier scholarship elaborates as law, statute, decree, reward and punishment, and Gongsun for lacking Shu, providing no method for control of the ministers. Han Fei and Li Si (the latter as quoted by Sima Qian) quote Shen Buhai as using Fa in the sense of what Creel translated as method, but never law.

Although the most frequently used term to describe Shen Buhai's doctrine, Han Fei's Shu (technique) does not appear in the Shen Buhai fragments. Only Shu (数 numbers) does, and only twice, although Creel takes this as also used in the sense of technique. Also describing wu-wei and Xing-Ming as techniques of government, although Shu is often translated as technique modernly, Creel more often translated Shu as method, as did Graham and Hansen.

Recalled by Tao Jiang, Creel takes Shu as a variety of Fa. Taken more broadly, unlike Graham neither did Creel or subsequently Hansen regard Fa as necessarily shifting towards law. While during the Warring States period law became prominent, and "we might expect Fa as law would become also more prominent", it is 'not clear' that it did. Fa as law appears to be newer than method or even technique, as represented by the term fa-shu, or method technique. While the development of Fa follows a logical progression, it is not a series of steps but "rather a scale of infinite gradations, like a spectrum."

Creel's broader argument says: "In the Zuo Zhuan Fa is fairly common, using Fa in the sense of law 'almost two thirds of the time.'" But it also uses it in the sense of regulation, example, model and to imitate. The Zhan Guo Ce (Strategems of the Warring Stated period) has Fa as law a little more than half the time. In the Guoyu (book) (Discourses of the States) Fa occurs as law less than half the time. In the Mozi, it occurs as law rarely, representing model almost half the time, and method or technique three times more frequently than law, particularly in relation to military procedure.

Accepting the unity of Fa and Shu, Graham took Han Fei as "distinguishing between law as public and method as private", with the need to distinguish varieties of Fa possibly sharpened by the contrast between Lord Yang and Shen Buhai, the latter who "did not use Shu (technique) but included it within Fa (standard)". Hansen would note the Qin empire as adopting the term Lu for their legal code, a term used rarely in older texts.

Although distinguishing the more standard or uniform usage of Shang Yang's Fa as including reward and punishment across the population, from the managerial practice of Shen Buhai, Hansen notes Han Fei as connecting his own practice of reward and punishments with Shu, in which ministers are held to performance standards they set for themselves, as hardly a Legalist practice. Han Fei considers shu nonsensical without objective standards (fa) independent of the ruler's desires, whose key aspect is it's inevitable, mechanical nature.[43]

The Oxford (2011)

As at least suitable to a basic introduction, Sinologist Chris Fraiser of the Oxford elaborates a modern interpretation of the three elements as attributable to their posthumous synthesis under Han Fei. Although discussed elsewhere, he does not for instance reference Feng Youlan here, whose scholarship is quite old anyway. Fraiser says: "The Legalists proposed a number of keys to successful government, which Han Fei draws together into a coherent system. He credits his precedessors with articulating three crucial concepts in particular: fa (standards,laws), which he attributes to Shang Yang; shu (arts, techniques), which he attributes to Shen Buhai; and shi (position,power), which he attributes to Shen Dao. He criticizes shortcomings in the approaches of all three men while showing how their common ideas can be combined into a cogent, unified theory."

Mr. Fraser defines Han Fei's Fa as including clear, explicit, specific, publicly promulgated standards of conduct encompassing laws, standards for satisfactory job performance, criteria for military and bureaucratic promotion, and regulation of the general population. Han Fei aims to replace inherited moral teachings and sage kings with Fa and its officials. Objective standards prevent deception of the ruler, their transparency prevents official corruption or abuse, and their exactness and public knowledge prevent bending or violation, controlling the population and limiting official power. Fa eliminates differences in treatment between the population and the bureaucracy or aristocracy.

Mr. Fraser defines Han Fei's Shu as managerial arts or techniques constituting undisclosed and uncodified methods. They include merit-based appointment, strict accountability in relation to job titles, and the employment of reward and punishment ensuring the performance of duties. Officials are assigned duties according to their administrative proposals, whose doctrine under Han Fei is called Xing-Ming. Shu is in part an inheritance of the Mohists who advocated meritocracy, and the doctrine of the rectification of names, which is shared with the Confucians and others.

Mr. Fraser elaborates Shi as connoting institutional power or advantageous position, wielded to implement the standards of conduct and administrative techniques. Based on the idea of the average ruler, it contrasts with the Confucian ideal of rule by moral worth and moral authority, which Han Fei sees as "foolishly unrealistic", condemning the state to constant misgovernment awaiting a sage king. It is secondly based on the idea of ruling and controlling a large number of people, which power and position can accomplish, but charisma cannot. Shi renders moral worth redundant. From a position of power, the ruler employs Fa, wields the handles of life and death, and uses techniques to manage the administration. [44]

Critique and defense of the Fajia's category

Saying that "The Legalists proposed a number of keys to succesful government", without much elaboration the Oxford suggests that not all of the thinkers are focused on Fa, criticizing the Fajia's category through the juxtaposition of a range of governmental methods against their singular element. On the other hand, Pines (2014-2022) variation on this criticism merely suggested that Fajia "reduces the rich intellectual content of this current to a single keyword."

Professor Tao Jiang (2021) compares critique of the Fajia's category against the three elements view, to address whether it is "appropriate to single out fa, over other key notions, as representing the thought of philosophers grouped under fajia." Tao Jiang takes Goldin (2011) as antagonist in rejecting the utility of both Legalism and Fajia as categories of interpretation. Like Goldin, taking them as recently discussed, central issues, Tao Jiang takes as his two primary questions whether the term Fajia can be anachronistically applied, and whether it should be translated as Legalism. Following Creel in differentiating Legalism from Fajia, Tao Jiang later argues in favor of Legalism's explorative value, but it's extensive discussion is outside this section's scope.

However, despite Goldin's rejection of the Fajia's category, in his focus on Fa and critique of Han Fei's three elements, his material can even be on drawn in support of Fa as key notion. The Fajia isn't his primary critique, nor does he particularly discuss the three elements apart from Fa. Taking Han Fei as antagonist for a three elements view, his critique of Fa as focus for Gongsun Yang simply suggests that his reforms are broader than Fa standards.

Being from the year of the Oxford's publishing, and of then continued relevance, Goldin can be observed to argue primarily against Legalism. While the first half of Goldin's essay discusses the Fajia and broad range of Fa, the second half further argues against Legalism, the rest being a critique of Han Fei. Goldin takes a critique of Legalism as his essay's "most important obligation", saying that "Creel’s objection to translating fajia as 'legalism'" is "still valid today and deserves to be repeated." Goldin includes references to a number of articles which still utilized Legalist interpretation, but unlike Winston many such documents do not contain actual arguments for a Legalist interpretation, merely adopting one.

Regarding Legalism, Goldin notes of Creel, even if one wishes to take Shang Yang, who engages statutes and a number of other questions from an administrative standpoint, as more Legalistic, the practices of Shen Buhai, which compare offices and performances, do not "presuppose a legal code or any legal consciousness whatsoever." Goldin's critique of the Fajia's category primarily considers Fajia "partisan and anachronistic"; it was coined by Sima Tan with an aim to "urge his particular brand of syncretism as the most versatile world view for his time."

To this point Tao Jiang instead adds Kidder Smith (2003), observing that "Sima Tan did not include any name under fajia". Goldin notes that while one might call oneself a Ru (Confucian), or pre-imperially a Mo (Mohists), no one ever actually called himself a Fajia, no Fa school actually existed, and no lineage actually existed. He also offers that the term jia can mean specialist or expert, but is critical on this point; they are intended to refer to schools of thought.

As to whether Fajia should be translated as Legalism, taking Creel as a theory, Tao Jiang says "since both Shang Yang and Shen Buhai were fajia but only Shang Yang was a Legalist, we can solve the problem by rejecting Legalism as the translation of Fajia." Rather, Creel takes Shang Yang as ancient China's Legalist school, and Han Fei as inadvertently responsible for the association of Shang Yang and Shen Buhai together in the Fajia. As for the Fajia, Tao Jiang references another Sinologist, Ivanhoe, who "defends the traditional Chinese use of jia to group classical thinkers by pointing out that jia 家 literally means family", whose intellectual families did not require relation by blood.

Goldin's three element's critique

While critical of the category itself, as noted Goldin actually devotes much of his essay to elaborating a variety of Fa. As with Hansen, Goldin makes an anti-Legalist comparison between the thinkers.

Goldin takes a tendency to "extol Han Fei as great synthesizer" at the expense of others as a sophisticated falsification, traceable to a self-serving depiction by Han Fei of "Shen Dao, Shen Buhai, and Gongsun Yang as authors of single political concepts", with only Han Fei combining them into a coherent philosophy. Han Fei says that Shen Buhai speaks of ‘technique’ (shu) and Gongsun Yang standards (fa). As Goldin notes, Shen Buhai "referred to fa quite often". As Creel notes, while Han Fei differentiates Shen Buhai using the term Shu, he does also quote Shen Buhai as using Fa. Goldin's critique nonetheless clarifies a view of the subject against the old three elements scheme.

As a critique of Legalism, Goldin says that that "it would be inappropriate to confine (Han Fei's) fa to the meaning of 'law'”, and as a critique of Han Fei, that "if anyone deserves to be recognized as a member of fajia, it is Shen Dao, who was criticized by Xunzi for being 'beclouded by fa'" (as opposed, notably, to shih). Goldin compares Shen Dao's Fa with Shen Buhai as an "impersonal administrative technique of determining rewards and punishments in accordance with a subject’s true merit" (according to Creel for Shen Buhai, more in the way of selection and promotion). Goldin does also consider Shen Dao as sometimes using Fa in a more Legalistic sense.

As a critique of Han Fei 's singular element for Gongsun Yang in Fa, Goldin takes Gongsun as addressing many other administrative questions from standards (Fa). Goldin says that Gongsun institutes a "principle of mutual responsibility such that each member of the group would be liable for the misconduct of any other", and "institutes a rigidly stratified society in which one’s status was tied entirely to one’s service to the state". Presenting Gongsun as also a military reformer, Goldin recalls Mark Edward Lewis, with Gongsun Yang’s "reorganization of the military" going so far as to redraw the map of Qin 秦", dividing up the countryside into an equalized grid, with blocks of rectangular land and evenly spaced agricultural fields.

Goldin refers here to the village watch groups themselves, rather than the penal law or standards they are compared against, which the Routledge does take as Fa (derivatively included as mechanically geared named wrongs). But to quote Pines: "The institutions of the state, fa in its broadest meaning, should be designed so as to channel social forces toward desirable social and political ends. This approach... is the hallmark of Shang Yang’s intellectual audacity." Hence, service to the state's standards, in Shang Yang's case agriculture and war.

Goldin concludes with regards Fa and Legalism that "Even in imperial China, fa tended to mean something more like “government program” or “institution” than “law”—as in, for example, the failed “Green Sprouts Policy” (Qingmiao fa 青苗法), which was Wang Anshi’s 王安石 (1021-1086) attempt to establish a government credit bureau."

Tao Jiang's three element's critique

Tao Jiang says: "Fa in the classical Chinese context has a different semantic range and connotations from law in the contemporary Western context. Fa can refer to method, standard, regulation, law, model, or (as a verb) to follow, etc. Hence, translating fa as law does not do justice to how the term is used and what it encompasses in the texts involved." Tao Jiang takes Goldin's common definition of Fa between Shen Buhai and Shen Dao as most relevant.

Recalled by Tao Jiang, Chinese scholar Soon-Ja Yang (2010) similarly considers Shen Dao's focus to be Fa, not Shi. Soon Ja Yang says: "Han Fei quotes Shen Dao not because Shen Dao focused on the concept of shi, but because it is Shen Dao who pointed out that political power or authority takes precedence over individual capabilities in achieving political control." This is not to say that Shen Dao does not discuss several other concepts, including human dispositions and professional virtues.

Tao Jiang otherwise takes Goldin as arguing that "Other well-known fajia tools include shu and shi. Therefore, from such a perspective it is misleading to single out fa as representing the core idea of those thinkers grouped under the nomenclature fajia or Legalism." Unfortunately, Tao Jiang does not reference a particular page, and while Goldin attempts to diversify Gongsun Yang, he does not discuss Shi. On the other hand, he reiterates Shen Buhai and Shen Dao as focused on Fa.

In defense of the Fajia against its purported opponent, Tao Jiang recalls Creel with Fa as coming to represent law, administrative method, and even managerial technique (Shu) as covering the bulk of their thought. Tao Jiang takes the Fajia as holding in common a focus in the institutionalization of political power, and a questioning of the moral values of the Confucians, disputing an assumed connection between personal virtue and political authority. Apart from Fa's generality, it has been argued that they are all in fact focused on Fa (Soon-ja Yang).

Although without Tao Jiang as reference, Pines subsequently abandons the Fa critique in favor of the Fa tradition. Pine's only remaining subsequent criticism of Fajia is the scope of the movement and the term's analytical usefulness. While Goldin states that "'Agriculture and war' (nong zhan 農戰) may have been (Gongsun's) single most important slogan", Goldin and Pines note that while fa can as often refer to “standards,” “models,” “norms,” “methods,” and the like, sometimes it refers to the entirety of political institutions. Although not in this case by direct reference, Pines differentiates Shu along similar lines to Graham's private arcanum, its private usage by the ruler having different consequences from its public manifestation.[45][1]

Power and the ruler's interest in earlier scholarship

Arthur Waley recounted shih as "power automatically derived from the mere fact of being king", while his discussion the ruler recounts shu as institution and anti-ministerialism. On the other hand, Waley presented a focus in the ruler's interest in connection with an early view of wu-wei, taking harsh legal punishments as allowing for relaxation by theruler. However, while Shang Yang's reliance on institutions can be compared to wu wei, neither the term nor Shen Buhai's formal concept is found in the Book of Lord Shang. While wu wei can be connected with tactics, refraining from an interference in managerial duties, Creel takes wu wei in the Shen Buhai fragments as as allowing for for productive management or rule in the first place.

A focus in the what Hansen terms "the ruler's point of view" as distinctive, in connection with power or shih depending, is prior represented in Wing-Tsit's 1963 encyclopedia, Roger T Ames (1983) Art of Rulership (1983), and later, Zhengyuan Fu's legal positivist popular literature, The Earliest Totalitarians (1996). Wing-tsit Chan (1963) described "Legalism" as the most radical of the schools, primarily interested in power, subjugation, uniformity, and force, recognizing no authority apart from the ruler. Han Fei calls the method he recommends to sovereigns the Way of the Ruler, and echoing Wing-tsit, Professor Roger T. Ames (1983) took Legalist political philosophy as "government of the ruler, by the ruler, for the ruler", involving control in the interests of "absolute power, stability, personal safety, military strength, wealth and luxury", although keeping in mind the strife giving rise to its "totalitarianism."

Covering a variety of topics, Ame's first statement of emphasis on anti-ministerialism and self-regulating systems is reiterated by the Oxford without Legalist priorities. In this regard Ames presents Shag Yang's law first, despite Creel and despite Han Fei's criticism of it's effectiveness for it. Ames presents Shen Buhai and Han Fei's bureaucratic organization as "another important system." He presents shih coupled with shu as "sufficient tools of control", notably taking wu wei or reduced ministerial activity by the ruler as perhaps their foremost technique of rulership. Despite taking the ruler's interest as primary, in contrast to Hansen, and prior to Graham, Ames is quite willing to connect these with an institutionalization of the ruler and government, presenting wu wei's anti-ministerialism secondarily to it's institutional function.

Hansen characterizes Han Feizi as the first Zi (master) from the ruling nobility. Eschewing ethics in favour of strategy, it is taken for granted that the goal of the ruler was conquest and unification of all under heaven. Although focused on Fa, and relegated as secondary by Han Fei as Shen Dao's doctrine of power or situationist authority (shi), Hansen takes Shen Buhai, Shang Yang, and Han Fei as all motivated "almost totally from the ruler's point of view". Hansen considered this as constituting a key difference between the Han Feizi and Western law, Confucianism, or the more universal social standpoint of Mohism, despite having an otherwise Mohist conceptual framework.

Fraiser would consider a primary difference between Mohist and Legalist Fa to be its arbitrariness in suiting the purposes of the ruler.

On the other hand, as Pines notes, although "the fa thinkers in general and Han Fei in particular are often condemned as defenders of 'monarchic despotism'", Graham viewed Han Fei’s system as making sense only “if seen from the viewpoint of the bureaucrat rather than the man at the top."

Shih as represented in Graham, as a contemporary directly discussed in Hansen's Han Feizi chapter, takes Han Fei's argument pertaining to shih as aiming at the ruler's irrelevancy, with the throne as institution. 'Legalism', Graham says, is lacking on discussions on De, or awe-inspiring personal potency; power shifts to simply occupying institutional positions. Graham says: "(Han Fei's) essay on Shen Dao's doctrine of power concludes that what is needed is not morality (as an adjunct to power) but law (fa)... what matters is whether the power-base itself is fully ordered; if it is, it will continue to impose orderly government throughout the Empire irrespective of the moral worth of the ruler. Both Shen Dao and the Confucian have been using shih 'power-base' in its common sense of a natural position of advantage in relation to others; but the strength of a throne depends on institutions made by man."

Soon-Ja Yang (2010) vacilitates against the idea that Han Feizi and the other ancient Chinese "Legalists" support absolutism, autocracy, despotism or tyranny, or that they sacrifice the people's interests for that of the ruler. He argues that Han Feizi even advocates ren 仁 (humanity), yi 義 (rightness), and li (propriety), otherwise modeling himself after nature, with Shu technique preventing a ruler from abusing their power and to put laws into practice with justice.

Chinese scholar Peng He (2014) argues that, although stressing the necessity of strengthening the ruler's force, they still emphasized the ruler's legitimacy, differing it therefore from western legal theories based on coercion. Although figures like Cao Cao and Sun Quan had force requiring obedience, the Romance of the Three Kingdoms prefers the blood-related Liu Bei whose laws are depicted as producing just behavior. Ruler-centric monarchical legitimation itself includes values beyond that of a pure consequentialism. Western monarchical legitimacy, Peng He recalls, similarly precedes western legalism, with Chinese Legalism not accomplishing its transformation as an ancient philosophy. But its laws, if taken as a bad, are still intended to produce a good, stressing rather that "ethical norms and morality should remain in the realm of family and private fields." "[46]

Decline of Laoist interpretation in earlier scholarship

Arthur Waley (1939) supposed a "very real and close connection" between what he termed Chinese "Realism" and Daoism, rejecting appeals to tradition and the way of the former kings, condemning book learning to keep the people dull and stupid, and advocacy of wu wei as a non-activity of the ruler, enabled by heavy penalties (with the Shangjunshu translated in 1928). This would not be an accurate characterization of the Shen Buhai fragments, which ignore penalties and take wu wei as a foundation in the management of bureaucracy.

By Creel's time, few critical scholars believed Laozi to have been a contemporary of Confucius, and Creel did not find Shen Buhai to be influenced by Daoist ideas. Because of this, as well as the apparent later timeline of the Daodejing's authorship, Creel instead suggest the possibility that Shen Buhai influenced the Daodejing—although Ames (1994) has suggested that few contemporary scholars take such chronologies at face value. Having previously noted the purported existence of the Yangists, as a qualification, Creel also does not exclude the possibility that Daoist ideas influenced the Fajia before they were written down in the Zhuangzi and Daodejing.

Not finding Huang-Lao itself before its mention in the Records of the Grand Historian, while Sima Qian may have asserted that Shen Buhai followed the doctrine of the Yellow Emperor or Huangdi, taking both as Daoist, Creel did not find the Yellow Emperor to have been accepted as a figure in the Daoist pantheon until after Shen Buhai's death. Although the editor hasn't sufficiently studied the issue, the Mawangdui excavation still dates after the Qin unification.

The Han Feizi is most similar to the Shen Buhai fragments, with Shen being prior prime minister of their native Hann state. Although there are old arguments for the legitimacy of much of the Han Feizi, Creel did not regard the Han Feizi's Daodejing commentary as having been written by Han Fei, which he notes as already generally accepted by scholarship at the time. Creel does however note that Shen Buhai quotes the Analects of Confucius, in which Wu Wei can also be seen as an idea. If anything, reviews suggested that Creel could have underestimated potential Confucian influence.

Graham reiterates however that the "Legalists" do not appear to make effective use of the Daodejing, as the Han dynasty Huainanzi does. The final chapter of the Zhuangzhi furthermore does not regard Lao Tzu and Zhuangzhi as having been part of a Daoist school. "The Way of Heaven" chapter regards Wu Wei as the first two stages of government, ministerial jobs and Confucian benevolence the third stage, responsibilities the fourth, shape and name the fifth, grounds for appointment the sixth, inquiry and inspection the seventh, approval and condemnation the eight, and reward and punishment the ninth. The Zhuangzi refers to those who start at the fifth stage as "men whose words turn the Way upside down."

Given its substantial evidences, the schools, Hansen says, are "after-the-fact inventions of Han historians." Taking Graham as theory, Hansen says, the Confucians and Mohists represent the earliest analysis and arguably only self-conscious pre-Han schools. The Outer Zhuangzi's developmental history of thought, excluding the Confucians, includes Mozi, Song Xing as another Mohist-derived school, Shendao, Laozi, and finally Zhuangzi. With the Zhuangzi taking him as one of their own, Shen Dao was a scholar early classed in the Han dynasty as Daojia, and only later Fajia. Essentially, the period knew neither Daoists nor Fajia. Sima Tan would claim that the Fajia studied his own daoistic Huang-Lao ideology. Hence, they may not initially have been taken as separate.

Essentially all Chinese philosophy uses the term Dao. Sinologist Yuri Pines (2022) suggests that the Han Feizi includes some metaphysical stipulation of political order. Outside of its Daodejing commentary, Daoist evidences are located more in located more in Chapters 20–21. "Sinology searches for the original text of the Daodejing, but it is restricted to written editions, of which the earliest complete ones date only as far back as the early Han dynasty. Its consensus view is that the original Daodejing is dated to just before then, at the end of the Warring States period, since there are no earlier textual records attesting to it." The Original Text of the Daodejing, 2022[47]

Fajia and the Fa tradition

Having previously used the popular term Legalist, with reference to Goldin, Pines (2023), modern translator for the Book of Lord Shang (2017), now characterizes them as the Fa tradition, calling them Fa thinkers. The term is shared by an as yet unpublished multi-authored work, the Dao Companion to China's fa Tradition. As stated by their publisher, the Dao Companions aim to provide the most comprehensive and up-to-date introductions to various aspects of Chinese philosophy.

Pines accounts the term Legalism as focusing the subject on comparisons with a modern rule of law, with such discussions common in early modern scholarship, undercuting the depth of the subject for questions that were not necessarily of primary importance for the theorists. Moreover, although with reference to the new work Pines takes law to be a correct translation for Fa in many contexts, he reiterates that it also often refers to “standards,” “models,” “norms,” and “methods". As mentioned, Shang Yang is generally taken to be the most Legalist of them if anything.

Tao Jiang (2021), as unfortunately unreferenced on Pine's page but otherwise considered by him a major achievement in the purportedly multi-authored Tao Jiang on the Fa Tradition, had previously argued for the legitimacy of Fajia within scholarship as a considered historical category denoting the commonality of Fa between the statesmen; Creel used it. Pine's Fa thinker's shares it's terminology of Thinker with Tao Jiang, Pine's review lauding the work as "engaging the thinkers as theorists rather than mere statesmen, immersed in a dialog with earlier thinkers and texts." While Creel's "disparate statesmen" is referenced by the Oxford, Creel did also refer to them as "Fajia thinkers."

Fajia's term is misleading, Pines says, because it implies a self-aware, organized intellectual current commensurate with the followers of Confucius 孔子 (551–479 BCE) or Mozi 墨子 (ca. 460–390 BCE), whereas no early thinker identified himself as a member of the Fajia (or "School of Fa.") As opposed to this, Tao Jiang emphasizes their political prominence as unusual among classical thinkers, standing "at the beginning of a top-down political revolution that would radically transform the subsequent political history of China."

Although characterizing Fa thinkers as political realists, as defended modernly to be more or less legitimate, Pines takes its usage as a designation to give the impression that "the opponents of fajia were mere idealists, which was not the case."[2][1][48][49]

Deng Xi

The logician Deng Xi (died 501 BCE), a contemporary of Confucius, is cited by Liu Xiang for the origin of the principle of Xing-Ming. Deng is regarded as the first proponent to advocate following the li, or pattern of things. A term which refers to the processing of jade, it would be utilized by the neo-mohists as the term identifying the logic and history of a thing in the growth of a proposition.

Serving as a minor official in the state of Zheng, Deng is reported to have drawn up a code of penal laws. Associated with litigation, he is said to have argued for the permissibility of contradictory propositions, engaging in hair-splitting debates on the interpretation of laws, "legal principles and definitions. But the purpose of his concept of bian is specifically to examine and distinguish categories so as to prevent hindrances or disturbances. Inferences are then made categorically.

However, he distinguishes great and small bian ethically rather than logically, as Xun Kuang would later (although the Mohists also had ethical discussions). Under the influence of the Mohists, Xun Kuang suggests that categorization is a key to understanding things.[50]

Shang Yang

Hailing from Wei, as Prime Minister of the State of Qin, Shang Yang (390–338 BCE) engaged in a "comprehensive plan to eliminate the hereditary aristocracy".[1] Drawing boundaries between private factions and the central, royal state, he took up the cause of meritocratic appointment, stating "Favoring one's relatives is tantamount to using self-interest as one's way, whereas that which is equal and just prevents selfishness from proceeding."

As the first of his accomplishments, historiographer Sima Qian accounts Shang Yang as having divided the populace into groups of five and ten, instituting a system of mutual responsibility tying status entirely to service to the state. It rewarded office and rank for martial exploits, going as far as to organize women's militias for siege defense.

The second accomplishment listed is forcing the populace to attend solely to agriculture (or women cloth production, including a possible sewing draft) and recruiting labour from other states. He abolished the old fixed landholding system (Fengjian) and direct primogeniture, making it possible for the people to buy and sell (usufruct) farmland, thereby encouraging the peasants of other states to come to Qin. The recommendation that farmers be allowed to buy office with grain was apparently only implemented much later, the first clear-cut instance in 243 BCE. Infanticide was prohibited.

Shang Yang deliberately produced equality of conditions amongst the ruled, a tight control of the economy, and encouraged total loyalty to the state, including censorship and reward for denunciation. "Law" as such was what the sovereign commanded, and this meant absolutism, but it was an absolutism of Fa (administrative standards) as impartial and impersonal, which Gongsun discouraged arbitrary tyranny or terror as destroying.

Emphasizing knowledge of the Fa among the people, he proposed an elaborate system for its distribution to allow them to hold ministers to it. He considered it the most important device for upholding the power of the state. Insisting that it be made known and applied equally to all, he posted it on pillars erected in the new capital. In 350, along with the creation of the new capital, a portion of Qin was divided into thirty-one counties, each "administered by a (presumably centrally appointed) magistrate". This was a "significant move toward centralizing Ch'in administrative power" and correspondingly reduced the power of hereditary landholders.

Shang Yang considered the sovereign to be a culmination in historical evolution, representing the interests of state, subject and stability.[51] Objectivity was a primary goal for him, wanting to be rid as much as possible of the subjective element in public affairs. The greatest good was order. History meant that feeling was now replaced by rational thought, and private considerations by public, accompanied by properties, prohibitions and restraints. In order to have prohibitions, it is necessary to have executioners, hence officials, and a supreme ruler. Virtuous men are replaced by qualified officials, objectively measured by Fa. The ruler should rely neither on his nor his officials' deliberations, but on the clarification of Fa. Everything should be done by Fa,[11]: 88 whose transparent system of standards will prevent any opportunities for corruption or abuse. [52][53][54]

Evolutionary view of history

What Pines terms the evolutionary view of history was regarded by the early scholarship of Feng Youlan (1948) as a commonality between Gongsun Yang and Han Fei. Discussed in our Realism introduction, Graham (1989) less radically formulates its philosophy as starting "not from how society ought to be but how it is", into which the tradition can be fitted more broadly. Graham adds to the two the Guanzi, which to the current's benefit is a text which may have been written even after the Han Feizi.

However, Creel did not epouse the more evolutionary progressivism we discuss here as a view of Shen Buhai. In contrast to Shang Yang, Shen's fragments take no issue in quoting the Analects. If taken as an extension of the subject, we cannot yet suggest Creel's Shen Bhai "branch" or post-Qin figures as noted for it.

While a changing with the times paradigm was common apart from the Confucians regardless, the difference has been taken more to be more matter of emphasis, and the elucidation in particular of a view held in the Book of Lord Shang. Even adding additional figures we can only present the more "progressive" variation of this tendency as more along the lines of the Shang Yang current or Qin-influenced figures.

Feng Youlan took the "Legalists" as fully understanding that needs change with the times. Admitting that people may have been more virtuous anciently, they maintained that this was due to material circumstances. Han Fei believes that new problems require new solutions. Although a view of history as a process of change may be common modernly, Feng Youlan suggests it contrasted with the beliefs of Ancient China.

In what Graham calls a "highly literary fiction in a stilted parallelistic style", the Book of Lord Shang opens with a debate held by Duke Xiao of Qin, seeking to "consider the changes in the affairs of the age, inquire into the basis for correcting standards, and seek the Way to employ the people." Gongsun attempts to persuade the Duke to change with the times, with the Shangjunshu citing him as saying: "Orderly generations did not [follow] a single way; to benefit the state, one need not imitate antiquity."

While Xun Kuang's doctrine held human nature to be bad, noting the existence of differences with regards Shen Buhai, Graham compared the "Legalists", Han Fei in particular, with the Malthusians, as "unique in seeking a historical cause of changing conditions", namely population growth. Human nature is a Confucian issue. The statesmen acknowledge that an underpopulated society only need moral ties. The Guanzi text sees punishment as unnecessary in ancient times with an abundance of resources, making it a question of poverty rather than human nature. Graham otherwise considers the customs current at the time as having no significance to them.

Hu Shih (essays 1919–1962) calls Xun Kuang, Han Fei and Li Si "champions of the idea of progress through conscious human effort," with Li Si abolishing the feudal system, and unifying the empire, law, language, thought and belief, presenting a memorial to the throne in which he condemns all those who “refused to study the present and believed only in the ancients on whose authority they dared to criticize."

Hu Shih quotes a song by Xun Kuang.

You glorify Nature and meditate on her:

Why not domesticate and regulate her?

You follow Nature and sing her praise:

Why not control her course and use it? … … … …

Therefore, I say: To neglect man’s effort and speculate about Nature,Is to misunderstand the facts of the universe.

As a counterpoint, Han Fei or Shen Dao do still employ argumentative reference to 'sage kings'; Han Fei claims the distinction between the ruler's interests and private interests are said to date back to Cangjie, while government by Fa is said to date back to time immemorial. Tao Jiang takes Han Fei's statements in this regard seriously, with Han Fei considering the demarcation between public and private a "key element" in the "enlightened governance" of the former kings.[55]

Anti-Confucianism

While Shen Buhai and Shen Dao's current may not have been hostile to Confucius,[13]: 64 Shang Yang and Han Fei emphasize their rejection of past models as unverifiable if not useless ("what was appropriate for the early kings is not appropriate for modern rulers").[56] Han Fei argued that the age of Li had given way to the age of Fa, with natural order giving way to social order and finally political order. Together with that of Xun Kuang, their sense of human progress and reason guided the Qin dynasty.[57]

Intending his Dao (way of government) to be both objective and publicly projectable,[25]: 352 Han Fei argued that disastrous results would occur if the ruler acted on arbitrary, ad-hoc decision making, such as that based on relationships or morality which, as a product of reason, are "particular and fallible". Li, or Confucian customs, and rule by example are also simply too ineffective.[58][59][60] The ruler cannot act on a case-by-case basis, and so must establish an overarching system, acting through Fa (administrative methods or standards). Fa is not partial to the noble, does not exclude ministers, and does not discriminate against the common people.[60]

Linking the "public" sphere with justice and objective standards, for Han Fei, the private and public had always opposed each other.[61] Taking after Shang Yang he lists the Confucians among his "five vermin",[62] and calls the Confucian teaching on love and compassion for the people the "stupid teaching" and "muddle-headed chatter",[63] the emphasis on benevolence an "aristocratic and elitist ideal" demanding that "all ordinary people of the time be like Confucius' disciples".[58] Moreover, he dismisses it as impracticable, saying that "In their settled knowledge, the literati are removed from the affairs of the state ... What can the ruler gain from their settled knowledge?",[64] and points out that "Confucianism" is not a unified body of thought.[65]