Christmas in Italy

Christmas in Italy (Italian: Natale) begins on December 8, with the feast of the Immaculate Conception, the day on which traditionally the Christmas tree is mounted and ends on January 6, of the following year with the Epiphany (Italian: Epifania).[2]

The term Natale derives from the Latin natalis, which literally means 'birth',[3] and the greetings in Italian are buon Natale (Merry Christmas) and felice Natale (Happy Christmas).[4]

Popular traditions

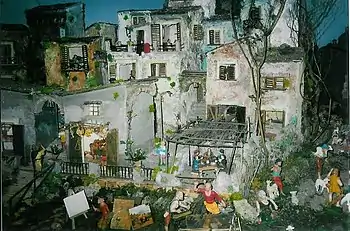

Nativity scene

The tradition of the nativity scene comes from Italy. What is considered the first nativity scene in history (a living nativity scene) was set up by St. Francis Of Assisi in Greccio in 1223.[5] However, nativity scenes were already found in Naples in 1025.[5] In Italy, regional crib traditions then spread, such as that of the Bolognese crib, the Genoese crib and the Neapolitan crib.

Yule log

The tradition of the Yule log, once widespread, has been attested in Italy since the 11th century. A detailed description of this tradition is given in a book printed in Milan in the fourteenth century.[6] The Yule log appears with different names depending on the region: in Tuscany it is known as ciocco,[7] while in Lombardy it is known as zocco.[8] In Val di Chiana, in Tuscany, it was customary for children, blindfolded, to hit the block with pincers, while the rest of the family sang the Ave Maria del Ceppo.[9] That tradition was once deeply rooted in Italy is demonstrated by the fact that Christmas in Tuscany was called the "feast of the log".[7]

Christmas tree

The tradition of the Christmas tree, of Germanic origin, was also widely adopted in Italy during the twentieth century. It seems that the first Christmas tree in Italy was erected at the Quirinal Palace at the behest of Queen Margherita, towards the end of the nineteenth century.[2]

During Fascism this custom was frowned upon and opposed (being considered an imitation of a foreign tradition), preferring the typically Italian nativity scene. In 1991, the Gubbio Christmas Tree, 650 meters high and decorated with over 700 lights, entered the Guinness Book of Records as the tallest Christmas tree in the world.[10]

Bagpipers

Typically Italian tradition is instead that of the bagpipers, or men dressed as shepherds and equipped with bagpipes, who come down from the mountains, playing Christmas music.[11] This tradition, dating back to the nineteenth century, is particularly widespread in the South of the country.[12]

A description of the Abruzzese bagpipers is provided by Héctor Berlioz in 1832.[11]

Bearers of gifts

Typical bearers of gifts from the Christmas period in Italy are Santa Lucia (December 13), Baby Jesus, Babbo Natale (the name given to Santa Claus), and, on Epiphany, the Befana.[13]

Santa Lucia

Traditional bearer of gifts in some areas of Northern Italy, such as Verona, Lodi, Cremona, Pavia, Brescia, Bergamo and Piacenza is Santa Lucia on the night between December 12 and 13.[14]

According to the Italian tradition, Saint Lucia shows up on her donkey and the children must leave a cup of tea for the saint and a plate of flour for the animal.[15]

Befana

A typical figure of Italian Christmas folklore is the Befana, depicted as an old witch on a broom, who appears as a bearer of gifts on January 6, the day of the Epiphany: according to tradition, this figure brings gifts (usually sweets inside of a sock) to good children and coal to bad children.[16]

The Befana, whose name is an altered form of the word Epifania, is a figure that can be connected to others that are also found in other cultures, such as the German Frau Berchta and the Russian Babuška.[16]

A famous nursery rhyme is dedicated to the figure of the Befana:

La Befana vien di Notte

con le scarpe tutte rotte

il cappello alla romana

viva viva la Befana

Gastronomy

According to tradition, the Christmas Eve dinner must not contain meat. A popular dish in Naples and the South is eel or capitone. A traditional dish from Northern Italy is capon (gelded chicken), consumed especially in Piedmont and Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Lamb is more common in Central Italy.[17]

Desserts

Panettone

Panettone is a typical Italian Christmas cake, a cake with raisins and candied fruit originally from Milan, but widespread throughout the territory.[18] The origins of this dessert probably date back to the 12th century.[19] The name panettone perhaps derives from pan del Ton, referring to one of the legends about the origins of this dessert, which was allegedly created by a scullery boy named Toni in the service of Duke Ludovico.[20] This Christmas cake was particularly appreciated by the writer Alessandro Manzoni and by the composer Giuseppe Verdi.[21][22]

Pandoro

Another typical Italian Christmas cake spread throughout the territory is pandoro, a sweet originally from Verona, created in 1884 by Domenico Melegatti.[19]

The name of this cake derives from pan de oro, in memory of a conical-shaped cake, which at the time of the Serenissima Republic was covered with pure gold leaves.[23]

Torrone

Originally from Northern Italy, but widespread throughout the country, is torrone. According to tradition, the nougat originated from a dessert served in Cremona on 25 October 1441 on the occasion of the wedding between Francesco Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti.[24]

Nougat

Nougat is eaten in Northern Italy, particularly Cologna Veneta. The origins of this dessert probably date back to the commercial relations that the Republic of Venice had with the East.[25]

Struffoli

From Southern Italy, especially Naples, but widespread throughout, are struffoli, a type of deep-fried dough. Known as early as the 17th century, the name may derive from the Greek strongoulos, which means 'round'.[26]

Background

20th century

In 1938, under fascism, the so-called "Fascist Befana" was introduced during the Christmas holidays, a demonstration for charitable purposes.[27]

21st century

Religious celebrations

Starting from December 16 and until Christmas Eve, the Christmas novena is recited in the Catholic Church.[28]

References

- "Il Natale accende Verona con le luminarie, alberi, stelle e proiezioni grafiche". Verona Sera (in Italian). Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "The Best Christmas Traditions in Italy". Walks of Italy. November 25, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Natale, origine del nome". Etimo Italiano (in Italian). Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Natale (italienische Weihnachten)". Mein Italien (in German). Archived from the original on April 28, 2009. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Christmas in Italy". Why Christmas. Archived from the original on December 15, 2005. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Supplementum Epigraphicum GraecumBeroia. In coemeterio Iudaeo. Stela a dextra fracta. Op. cit. 185". Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. doi:10.1163/1874-6772_seg_a2_399. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "La tradizione del ceppo in Toscana – Consulenza Linguistica – Accademia della Crusca". Accademia della Crusca (in Italian). Archived from the original on December 25, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Natale 2020, la tradizione del ceppo in Lombardia". Il Giorno (in Italian). Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Natale in Valdichiana Senese". ValdichianaLiving.it (in Italian). Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Celebrate Christmas Italian Styles at These City Events". TripSavvy. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Mein Italien – Zampognari". www.mein-italien.info. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Supplementum Epigraphicum GraecumSivrihissar (in vico). Op. cit. Op. cit. 334, n. 19". Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. doi:10.1163/1874-6772_seg_a2_597. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "La storia della Befana". Festa della Befana (in Italian). Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Santa Lucia su santiebeati.it". Santiebeati.it. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Santa Lucia: tradizioni ricorrenti in tutta Italia". Club Med Magazine (in Italian). November 30, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Supplementum Epigraphicum GraecumÖrén. Fragm. coronae. Op. cit. 67, n. 71. Suppl. Cr". Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. doi:10.1163/1874-6772_seg_a2_688. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "La triade golosa del Natale italiano: cappone, abbacchio e capitone". lacucinaitaliana.it (in Italian). Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- "Mein Italien – Panettone & Co". Mein Italien (in German). Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Storia del panettone e del pandoro – Il mondo Sale e Pepe – Blog – Sale e Pepe Group – Gastronomia, Catering, Banqueting" (in Italian). December 8, 2015. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Il PAN del TON: l'origine del PANETTONE è Lombarda, anzi milanese..." 24 Ore News (in Italian). December 12, 2010. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Il panettone? Piaceva anche a Manzoni… – CentoArchi Edizioni". centoarchi.com (in Italian). Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Il panettone sulla tavola di Natale di Giuseppe Verdi". Arte e Arti Magazine (in Italian). December 15, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- Armano, In cibo veritas di Michele (December 22, 2014). "PAN DE ORO, dolce mistero dal 1884". Ildenaro.it (in Italian). Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Storia del mandorlato | Torronificio Scaldaferro" (in Italian). January 1, 2016. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "In Veneto | Torronificio Scaldaferro" (in Italian). March 5, 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Storia degli struffoli". www.taccuinigastrosofici.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Mein Italien – La befana". Mein Italien (in German). Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Novena di Natale, cos'è, quando nasce e cosa significa". Famiglia Cristiana (in Italian). Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

External links

Media related to Christmas in Italy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Christmas in Italy at Wikimedia Commons