Colonoscopy

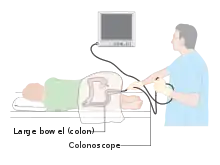

Colonoscopy (/ˌkɒləˈnɒskəpi/) or coloscopy (/kəˈlɒskəpi/)[1] is the endoscopic examination of the large bowel and the distal part of the small bowel with a CCD camera or a fiber optic camera on a flexible tube passed through the anus. It can provide a visual diagnosis (e.g., ulceration, polyps) and grants the opportunity for biopsy or removal of suspected colorectal cancer lesions.

| Colonoscopy | |

|---|---|

Colonoscopy being performed | |

| ICD-9-CM | 45.23 |

| MeSH | D003113 |

| OPS-301 code | 1-650 |

| MedlinePlus | 003886 |

Colonoscopy is similar to sigmoidoscopy—the difference being related to which parts of the colon each can examine. A colonoscopy allows an examination of the entire colon (1,200–1,500 mm in length). A sigmoidoscopy allows an examination of the distal portion (about 600 mm) of the colon, which may be sufficient because benefits to cancer survival of colonoscopy have been limited to the detection of lesions in the distal portion of the colon.[2][3][4]

A sigmoidoscopy is often used as a screening procedure for a full colonoscopy, often done in conjunction with a fecal occult blood test (FOBT). About 5% of these screened patients are referred to colonoscopy.[5]

Medical uses

Conditions that call for colonoscopies include gastrointestinal hemorrhage, unexplained changes in bowel habit and suspicion of malignancy. Colonoscopies are often used to diagnose colon polyp and colon cancer,[6] but are also frequently used to diagnose inflammatory bowel disease.[7]

Fecal occult blood is a quick test which can be done to test for microscopic traces of blood in the stool. A positive test is almost always an indication to do a colonoscopy. In most cases the positive result is just due to hemorrhoids; however, it can also be due to diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis), colon cancer, or polyps. Colonic polypectomy has become a routine part of colonoscopy, allowing quick and simple removal of polyps during the procedure, without invasive surgery.[8]

Colon cancer screening

Colonoscopy is one of the colorectal cancer screening tests available to people in the US who are 45 years of age and older. The other screening tests include flexible sigmoidoscopy, double-contrast barium enema, computed tomographic (CT) colongraphy (virtual colonoscopy), guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and multitarget stool DNA screening test (Cologuard).[9]

Subsequent rescreenings are then scheduled based on the initial results found, with a five- or ten-year recall being common for colonoscopies that produce normal results.[10][11] People with a family history of colon cancer are often first screened during their teenage years. Among people who have had an initial colonoscopy that found no polyps, the risk of developing colorectal cancer within five years is extremely low. Therefore, there is no need for those people to have another colonoscopy sooner than five years after the first screening.[12][13]

Some medical societies in the US recommend a screening colonoscopy every 10 years beginning at age 50 for adults without increased risk for colorectal cancer.[14] Research shows that the risk of cancer is low for 10 years if a high-quality colonoscopy does not detect cancer, so tests for this purpose are indicated every ten years.[14][15]

Colonoscopy screening is associated with approximately two-thirds fewer deaths due to colorectal cancers on the left side of the colon, and is not associated with a significant reduction in deaths from right-sided disease. It is speculated that colonoscopy might reduce rates of death from colon cancer by detecting some colon polyps and cancers on the left side of the colon early enough that they may be treated, and a smaller number on the right side.[2] Many of these left-sided growths would have been detected by a sigmoidoscopy procedure.

Since polyps often take 10 to 15 years to transform into cancer in someone at average risk of colorectal cancer, guidelines recommend 10 years after a normal screening colonoscopy before the next colonoscopy. (This interval does not apply to people at high risk of colorectal cancer or those who experience symptoms of the disease.)[16][17]

The large randomized pragmatic clinical trial NordICC was the first published trial on the use of colonoscopy as a screening test to prevent colorectal cancer, related death, and death from any cause. It included 84,585 healthy men and women aged 55 to 64 years in Poland, Norway, and Sweden, who were randomized to either receive an invitation to undergo a single screening colonoscopy (invited group) or to receive no invitation or screening (usual-care group). Of the 28,220 people in the invited group, 11,843 (42.0%) underwent screening. A total of 15 people who underwent colonoscopy (0.13%) had major bleeding after polyp removal. None of the participants experienced a colon perforation due to colonoscopy. After 10 years, an intention-to-screen analysis showed a significant relative risk reduction of 18% in the risk of colorectal cancer (0.98% in the invited group vs. 1.20% in the usual-care group). The analysis showed no significant change in the risk of death from colorectal cancer (0.28% vs. 0.31%) or in the risk of death from any cause (11.03% vs. 11.04%). To prevent one case of colorectal cancer, 455 invitations to colonoscopy were required.[18][19]

The CONFIRM trial, a randomized trial on colonoscopy vs. FIT is currently ongoing.[20]

Recommendations

The American Cancer Society recommends, beginning at age 45, both men and women follow one of these testing schedules for screening to find colon polyps and/or cancer:[21]

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, or

- Colonoscopy every 10 years, or

- Double-contrast barium enema every 5 years, or

- CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) every 5 years

- Yearly guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT)

- Yearly fecal immunochemical test (FIT)

- Stool DNA test (sDNA) every 3 years

Medicare coverage

In the United States, Medicare insurance covers the following colorectal-cancer screening tests:[22]

- Colonoscopy: average risk — every 10 years beginning at age 50, high risk — every 2 years with no age restriction[23]

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy — every 4 years beginning at age 50[24]

- Double-contrast barium enema: average risk — every 4 years beginning at age 50, high risk — every 2 years[25]

- (CT) colonography: not covered by Medicare

- gFOBT: average risk — every year beginning at age 50[26]

- FIT: average risk — every year beginning at age 50

- Cologuard: average risk — every 3 years beginning at age 50[27]

Risks

About 1 in 200 people who undergo a colonoscopy experience a serious complication.[28] Perforation of the colon occurs in about 1 in 2000 procedures, bleeding in 2.6 per 1000, and death in 3 per 100,000,[29] with an overall risk of serious complications of 0.35%.[30][31]

In some low-risk populations screening by colonoscopy in the absence of symptoms does not outweigh the risks of the procedure. For example, the odds of developing colorectal cancer between the ages of 20 and 40 in the absence of specific risk factors are about 1 in 1,250 (0.08%).[32]

Perforation

The most serious complication is generally gastrointestinal perforation, which is life-threatening and in most cases requires immediate major surgery for repair.[33] Fewer than 20% of cases may be successfully managed with a conservative (non-surgical) approach.[33]

A 2003 analysis of the relative risks of sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy brought to attention the risk of perforation after colonoscopy is approximately double that after sigmoidoscopy (consistent with the fact that colonoscopy examines a longer section of the colon), a difference that appeared to be decreasing.[34]

Anaesthesia

As with any procedure involving anaesthesia, other complications would include cardiopulmonary complications such as a temporary drop in blood pressure and oxygen saturation usually the result of overmedication, and are easily reversed. Anesthesia can also increase the risk of developing blood clots and lead to pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis. (DVT)[35]

Bowel preparation

Dehydration caused by the laxatives that are usually administered during the bowel preparation for colonoscopy also may occur. Therefore, patients must drink large amounts of fluids during the day of colonoscopy preparation to prevent dehydration. Loss of electrolytes or dehydration is a potential risk that can even prove deadly.[35] In rare cases, severe dehydration can lead to kidney damage or dysfunction under the form of phosphate nephropathy.[36]

Other

During colonoscopies where a polyp is removed (a polypectomy), the risk of complications has been higher, although still low at about 2.3 percent.[30] One of the most serious complications is postpolypectomy coagulation syndrome, which occurs following about 1% of colonoscopies with electrocautery polypectomy. It results from a burn injury to the wall of the gastrointestinal tract and causes abdominal pain, fever, elevated white blood cell count and elevated serum C-reactive protein. Treatment consists of intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and avoiding any oral intake of food, water, etc. until symptoms improve. Risk factors include right colon polypectomy, large polyp size (>2 cm), non-polypoid lesions (laterally spreading lesions), and hypertension.

Bowel infections are a potential colonoscopy risk, although rare. The colon is not a sterile environment; many bacteria that normally live in the colon ensure the well-functioning of the bowel, and the risk of infections is minimal. Infections can occur during biopsies when too much tissue is removed and bacteria protrude in areas they do not belong to, or in cases when the lining of the colon is perforated and the bacteria get into the abdominal cavity.[37] Infection may also be transmitted between patients if the colonoscope is not cleaned and sterilized properly between tests.

Minor colonoscopy risks may include nausea, vomiting or allergies to the sedatives that are used. If medication is given intravenously, the vein may become irritated. Most localized irritations to the vein leave a tender lump lasting a number of days but going away eventually.[38] The incidence of these complications is less than 1%.

On rare occasions, intracolonic explosion may occur.[39] A meticulous bowel preparation is the key to prevent this complication.[39]

Signs of complications include severe abdominal pain, fevers and chills, or rectal bleeding (more than half a cup or 100ml).[40]

Procedure

Preparation

The colon must be free of solid matter for the test to be performed properly.[41] For one to three days, the patient is required to follow a low fiber or clear-liquid-only diet. Examples of clear fluids are apple juice, chicken and/or beef broth or bouillon, lemon-lime soda, lemonade, sports drink, and water. It is important that the patient remains hydrated. Sports drinks contain electrolytes which are depleted during the purging of the bowel. Drinks containing fiber such as prune and orange juice should not be consumed, nor should liquids dyed red, purple, orange, or sometimes brown; however, cola is allowed. In most cases, tea or coffee taken without milk are allowed.[42]

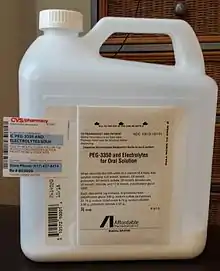

The day before the colonoscopy (or colorectal surgery), the patient is either given a laxative preparation (such as bisacodyl, phospho soda, sodium picosulfate, or sodium phosphate and/or magnesium citrate) and large quantities of fluid, or whole bowel irrigation is performed using a solution of polyethylene glycol and electrolytes.[43][44] The procedure may involve both a pill-form laxative and a bowel irrigation preparation with the polyethylene glycol powder dissolved into any clear liquid, such as a sports drink that contains electrolytes.

A typical procedure regimen then would be as follows: in the morning of the day before the procedure, a 238 g bottle of polyethylene glycol powder should be poured into 1.9 litres (64 oz.) of the chosen clear liquid, which then should be mixed and refrigerated. Two bisacodyl 5 mg tablets are taken 3 pm; at 5 pm, the patient starts drinking the mixture (approx. 8 oz. (0.5 litres) each 15-30 min. until finished); at 8 pm, take two bisacodyl 5 mg tablets; continue drinking/hydrating into the evening until bedtime with clear permitted fluids. The procedure may be scheduled early in the day so the patient need not go without food and only limited fluids until later.

The patient may be asked not to take aspirin or similar products such as salicylate, ibuprofen, etc. for up to ten days before the procedure to avoid the risk of bleeding if a polypectomy is performed during the procedure. A blood test may be performed before the procedure.[45]

Investigation

During the procedure the patient is often given sedation intravenously, employing agents such as fentanyl or midazolam. Although meperidine (Demerol) may be used as an alternative to fentanyl, the concern of seizures has relegated this agent to second choice for sedation behind the combination of fentanyl and midazolam. The average person will receive a combination of these two drugs, usually between 25 and 100 µg IV fentanyl and 1–4 mg IV midazolam. Sedation practices vary between practitioners and nations; in some clinics in Norway, sedation is rarely administered.[46][47]

Some endoscopists are experimenting with, or routinely use, alternative or additional methods such as nitrous oxide[48][49] and propofol,[50] which have advantages and disadvantages relating to recovery time (particularly the duration of amnesia after the procedure is complete), patient experience, and the degree of supervision needed for safe administration. This sedation is called "twilight anesthesia". For some patients it is not fully effective, so they are indeed awake for the procedure and can watch the inside of their colon on the color monitor. Substituting propofol for midazolam, which gives the patient quicker recovery, is gaining wider use, but requires closer monitoring of respiration.

A meta-analysis found that playing music improves tolerability to patients of the procedure.[51]

The first step is usually a digital rectal examination, to examine the tone of the sphincter and to determine if preparation has been adequate. The endoscope is then passed through the anus up the rectum, the colon (sigmoid, descending, transverse and ascending colon, the cecum), and ultimately the terminal ileum. The endoscope has a movable tip and multiple channels for instrumentation, air, suction and light. The bowel is occasionally insufflated with air to maximize visibility (a procedure that gives the patient the false sensation of needing to take a bowel movement).[52] Biopsies are frequently taken for histology. Additionally in a procedure known as chromoendoscopy, a contrast-dye (such as indigo carmine) may be sprayed through the endoscope onto the bowel wall to help visualise any abnormalities in the mucosal morphology. A Cochrane review updated in 2016 found strong evidence that chromoscopy enhances the detection of cancerous tumours in the colon and rectum.[53]

In most experienced hands, the endoscope is advanced to the junction of where the colon and small bowel join up (cecum) in under 10 minutes in 95% of cases. Due to tight turns and redundancy in areas of the colon that are not "fixed", loops may form in which advancement of the endoscope creates a "bowing" effect that causes the tip to actually retract. These loops often result in discomfort due to stretching of the colon and its associated mesentery. Manoeuvres to "reduce" or remove the loop include pulling the endoscope backwards while twisting it. Alternatively, body position changes and abdominal support from external hand pressure can often "straighten" the endoscope to allow the scope to move forward. In a minority of patients, looping is often cited as a cause for an incomplete examination. Usage of alternative instruments leading to completion of the examination has been investigated, including use of pediatric colonoscope, push enteroscope and upper GI endoscope variants.[54]

For screening purposes, a closer visual inspection is then often performed upon withdrawal of the endoscope over the course of 20 to 25 minutes. Lawsuits over missed cancerous lesions have recently prompted some institutions to better document withdrawal time as rapid withdrawal times may be a source of potential medical legal liability.[55] This is often a real concern in clinical settings where high caseloads could provide financial incentive to complete colonoscopies as quickly as possible.

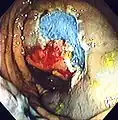

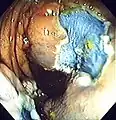

Polyp is identified.

Polyp is identified. A sterile solution is injected under the polyp to lift it away from deeper tissues.

A sterile solution is injected under the polyp to lift it away from deeper tissues. A portion of the polyp is now removed.

A portion of the polyp is now removed. The polyp is fully removed.

The polyp is fully removed.

Pain management

The pain associated with the procedure is not caused by the insertion of the scope but rather by the inflation of the colon in order to do the inspection. The scope itself is essentially a long, flexible tube about a centimeter in diameter — that is, as big around as the little finger, which is less than the diameter of an average stool.

The colon is wrinkled and corrugated, somewhat like an accordion or a clothes-dryer exhaust tube, which gives it the large surface area needed for water absorption. In order to inspect this surface thoroughly, the physician blows it up like a balloon, using air from a compressor or carbon dioxide from a gas bottle (CO2 is absorbed into the bloodstream through the mucosal lining of the colon much faster than air and then exhaled through the lungs which is associated with less post procedural pain), in order to get the creases out. The stomach, intestines, and colon have a so-called "second brain" wrapped around them, which autonomously runs the chemical factory of digestion.[56] It uses complex hormone signals and nerve signals to communicate with the brain and the rest of the body. Normally a colon's job is to digest food and regulate the intestinal flora. The harmful bacteria in rancid food, for example, creates gas.

The colon has distension sensors that can tell when there is unexpected gas pushing the colon walls out—thus the "second brain" tells the person that he or she is having intestinal difficulties by way of the sensation of nausea. Doctors typically recommend either total anesthesia or a partial twilight sedative to either preclude or to lessen the patient's awareness of pain or discomfort, or just the unusual sensations of the procedure. Once the colon has been inflated, the doctor inspects it with the scope as it is slowly pulled backward. If any polyps are found they are then cut out for later biopsy.

Some doctors prefer to work with totally anesthetized patients inasmuch as the lack of any perceived pain or discomfort allows for a leisurely examination. Twilight sedation is, however, inherently safer than general anesthesia; it also allows the patients to follow simple commands and even to watch the procedure on a closed-circuit monitor. Tens of millions of adults annually need to have colonoscopies, and yet many don't because of concerns about the procedure.

Colonoscopy can be carried out without any sedation and without problems with pain, which is practised in several institutions in many countries with the patient's agreement. This allows the patient to shift the body position to help the doctor carry out the procedure and significantly reduces recovery time and side-effects.[57] There is some discomfort when the colon is distended with air, but this is not usually particularly painful, and it passes relatively quickly. Unsedated patients can be released from the hospital on their own without any feelings of nausea, able to continue with normal activities, and without the need for an escort as recommended after sedation.

Ultrasound

Duodenography and colonography are performed like a standard abdominal examination using B-mode and color flow Doppler ultrasonography using a low frequency transducer — for example a 2.5 MHz — and a high frequency transducer, for example a 7.5 MHz probe. Detailed examination of duodenal walls and folds, colonic walls and haustra was performed using a 7.5 MHz probe. Deeply located abdominal structures were examined using 2.5 MHz probe. All ultrasound examinations are performed after overnight fasting (for at least 16 hours) using standard scanning procedure. Subjects are examined with and without water contrast. Water contrast imaging is performed by having adult subjects take at least one liter of water prior to examination. Patients are examined in the supine, left posterior oblique, and left lateral decubitus positions using the intercostal and subcostal approaches. The liver, gall bladder, spleen, pancreas, duodenum, colon, and kidneys are routinely evaluated in all patients.

With patient lying supine, the examination of the duodenum with high frequency ultrasound duodenography is performed with 7.5 MHz probe placed in the right upper abdomen, and central epigastric successively; for high frequency ultrasound colonography, the ascending colon, is examined with starting point usually midway of an imaginary line running from the iliac crest to the umbilicus and proceeding cephalid through the right mid abdomen; for the descending colon, the examination begins from the left upper abdomen proceeding caudally and traversing the left mid abdomen and left lower abdomen, terminating at the sigmoid colon in the lower pelvic region. Color flow Doppler sonography is used to examine the localization of lesions in relation to vessels. All measurements of diameter and wall thickness are performed with built-in software. Measurements are taken between peristaltic waves.[58]

Economics

Researchers have found that older patients with three or more significant health problems (i.e., dementia or heart failure) had higher rates of repeat colonoscopies without medical indications. These patients are less likely to live long enough to develop colon cancer. Gordon states, "At about $1,000 per procedure, there's clearly an economic incentive".[17]

The Hemoccult II FOBT (combined with follow-up colonoscopy if indicated by the test) is over 5 times as cost effective as other screening strategies, but is only about 85% as sensitive. Because of this relatively low sensitivity, US guidelines advocate the over 5 times more expensive procedures instead, because even the relatively small increase in lives saved and 5-fold cost increase is seen as worth choosing, given US living standards.[59]

History

In the 1960s, Dr. Niwa and Dr. Yamagata at Tokyo University developed the device. After 1968, Dr. William Wolff and Dr. Hiromi Shinya pioneered the development of the colonoscope.[60] Their invention, in 1969 in Japan, was an advance over the barium enema and the flexible sigmoidoscope because it allowed for the visualization and removal of polyps from the entire large intestine. Wolff and Shinya advocated for their invention and published much of the early evidence needed to overcome skepticism about the device's safety and efficacy.

Colonoscopy with CCD invention and market is led by Fuji film, Olympus and Hoya in Japan.[61] In 1982, Dr. Lawrence Kaplan of Aspen Medical Group in St. Paul, MN reported a series of 100 consecutive colonoscopies and upper endoscopies performed in a free-standing clinic miles from the nearest hospital, demonstrating the safety and cost effectiveness of these outpatient procedures. (Personal communication to the Joint Commission on Ambulatory Care, May 1983)

Etymology

The terms colonoscopy[62][63][64] or coloscopy[63] are derived from[63] the ancient Greek noun κόλον, same as English colon,[65] and the verb σκοπεῖν, look (in)to, examine.[65] The term colonoscopy is however ill-constructed,[66] as this form supposes that the first part of the compound consists of a possible root κολων- or κολον-, with the connecting vowel -o, instead of the root κόλ- of κόλον.[66] A compound such as κολωνοειδής, like a hill,[65] (with the additional -on-) is derived from the ancient Greek word κολώνη or κολωνός, hill.[65] Similarly, colonoscopy (with the additional -on-) can literally be translated as examination of the hill,[66] instead of the examination of the colon.

In English, multiple words exist that are derived from κόλον, such as colectomy,[63][67] colocentesis,[63] colopathy,[63] and colostomy[63] among many others, that actually lack the incorrect additional -on-. A few compound words such as colonopathy have doublets with -on- inserted.[63][64]

See also

References

- American Heritage Medical Dictionary

- Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L (January 2009). "Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer". Ann. Intern. Med. 150 (1): 1–8. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00306. PMID 19075198. as PDF Archived January 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Singh H, Nugent Z, Mahmud SM, Demers AA, Bernstein CN (March 2010). "Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published studies". Am J Gastroenterol. 105 (3): 663–673. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.650. PMID 19904239. S2CID 11145247.

- Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Alterhofen L, Haug U (January 2010). "Protection from right- and left-sided colorectal neoplasms after colonoscopy: population-based study". J Natl Cancer Inst. 102 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1093/jnci/djp436. PMID 20042716.

- Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, et al. (May 2010). "Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 375 (9726): 1624–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60551-X. PMID 20430429. S2CID 15194212. as PDF Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Colonoscopy". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- "Colonoscopy". Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. 7 December 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- Sivak Jr., Michael V. (December 2004). "Polypectomy: Looking Back". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 60 (6): 977–982. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02380-6. PMID 15605015.

- "Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Early Detection" (PDF). American Cancer Society. February 5, 2015. pp. 16–24. Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, et al. (June 2002). "Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 97 (6): 1296–1308. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05812.x. PMID 12094842. S2CID 26250449.

- Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, et al. (2017). "Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". American Journal of Gastroenterology. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health). 112 (7): 1016–1030. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.174. ISSN 0002-9270. PMID 28555630. S2CID 6808521.

- Gmperiale, Thomas F.; Glowinski, Elizabeth A.; Lin-Cooper, Ching; Larkin, Gregory N.; Rogge, James D.; Ransohoff, David F. (2008). "Five-Year Risk of Colorectal Neoplasia after Negative Screening Colonoscopy". N Engl J Med. 359 (12): 1218–1224. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0803597. PMID 18799558.

- No Need to Repeat Colonoscopy Until 5 Years After First Screening Newswise, Retrieved on September 17, 2008.

- Winawer, S.; Fletcher, R.; Rex, D.; Bond, J.; Burt, R.; Ferrucci, J.; Ganiats, T.; Levin, T.; Woolf, S.; Johnson, D.; Kirk, L.; Litin, S.; Simmang, C.; Gastrointestinal Consortium, P. (2003). "Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: Clinical guidelines and rationale—Update based on new evidence". Gastroenterology. 124 (2): 544–560. doi:10.1053/gast.2003.50044. PMID 12557158.

- American Gastroenterological Association, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Gastroenterological Association, archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2012, retrieved August 17, 2012

- Cancerconnect, Interval between Colonoscopies May be Shorter than Recommended Archived 2011-08-07 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 2 June 2011)

- Goodwin JS, Singh A, Reddy N, Riall TS, Kuo YF (August 2011). "Overuse of screening colonoscopy in the medicare population". Arch. Intern. Med. 171 (15): 1335–43. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.212. PMC 3856662. PMID 21555653. Archived from the original on 2011-09-01. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- Bretthauer, M; Løberg, M; Wieszczy, P; Kalager, M; Emilsson, L; Garborg, K; Rupinski, M; Dekker, E; Spaander, M; Bugajski, M; Holme, Ø; Zauber, AG; Pilonis, ND; Mroz, A; Kuipers, EJ; Shi, J; Hernán, MA; Adami, HO; Regula, J; Hoff, G; Kaminski, MF; NordICC Study, Group (27 October 2022). "Effect of Colonoscopy Screening on Risks of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death". The New England Journal of Medicine. 387 (17): 1547–1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2208375. hdl:10852/101829. PMID 36214590. S2CID 252778114.

- Clinical trial number NCT00883792 for "The Northern-European Initiative on Colorectal Cancer (NordICC)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- "Colonoscopy Versus Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality From Colorectal Cancer (CONFIRM) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- "American Cancer Society Guideline for Colorectal Cancer Screening". cancer.org. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- "Your Medicare Coverage: Colorectal cancer screenings". Medicare.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- "Screening colonoscopies". Medicare.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-06-26. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- "Screening flexible sigmoidoscopies". Medicare.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-06-26. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- "Screening barium enemas". Medicare.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-06-26. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- "Screening fecal occult blood tests". Medicare.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-06-26. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- "Multi-target stool DNA tests". Medicare.gov. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- Levin TR, Zhao W, Conell C, et al. (December 2006). "Complications of colonoscopy in an integrated health care delivery system". Ann. Intern. Med. 145 (12): 880–6. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00004. PMID 17179057. S2CID 12401206.

- Reumkens, A; Rondagh, EJ; Bakker, CM; Winkens, B; Masclee, AA; Sanduleanu, S (August 2016). "Post-Colonoscopy Complications: A Systematic Review, Time Trends, and Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 111 (8): 1092–101. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.234. PMID 27296945. S2CID 19186057.

- "Colonoscopy Risks". Archived from the original on 2012-11-18. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- J. A. Dominitz, et al., American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, "Complications of Colonsocopy", Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Vol 57, No. 4, 2003, pp. 441-445

- Cancer of the colon and rectum (invasive). SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2009

- Sartelli M, Viale P, Catena F, Ansaloni L, Moore E, Malangoni M, et al. (2013). "2013 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections". World J Emerg Surg (Review). 8 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1749-7922-8-3. PMC 3545734. PMID 23294512.

- Gatto, NM; Frucht H; Sundararajan V; Jacobson JS; Grann VR; Neugut AI (5 Feb 2003). "Risk of Perforation After Colonoscopy and Sigmoidoscopy: A Population-Based Study". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 95 (3): 230–6. doi:10.1093/jnci/95.3.230. PMID 12569145.

- "What are the colonoscopy risks?: Colonoscopy Risks That Become Potential Colonoscopy Complications". 4 August 2009. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Lien YH (September 2008). "Is bowel preparation before colonoscopy a risky business for the kidney?". Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 4 (11): 606–14. doi:10.1038/ncpneph0939. PMID 18797448. S2CID 340122.

- "Bowel Infections". Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- "What to expect after a colonoscopy?". Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Ladas SD, Karamanolis G, Ben-Soussan E (2007). "Colonic gas explosion during therapeutic colonoscopy with electrocautery". World J Gastroenterol (Review). 13 (40): 5295–8. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i40.5295. PMC 4171316. PMID 17879396.

- "Colonoscopy A Guide to the Procedure". Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, et al. (2014). "Optimizing Adequacy of Bowel Cleansing for Colonoscopy: Recommendations From the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". Gastroenterology. Elsevier BV. 147 (4): 903–924. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.002. ISSN 0016-5085. PMID 25239068.

- Waye, Jerome D.; Rex, Douglas K.; Williams, Christopher Beverley (2003). Colonoscopy: principles and practice. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-1-4051-1449-3.

- Hung, Shih-Ya; Chen, Hong-Chang; Chen, William Tzu-Liang (27 March 2020). "A Randomized Trial Comparing the Bowel Cleansing Efficacy of Sodium Picosulfate/Magnesium Citrate and Polyethylene Glycol/Bisacodyl (The Bowklean Study)". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 5604. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.5604H. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-62120-w. PMC 7101403. PMID 32221332.

- Kumar, Anjali S.; Kelleher, Deirdre C.; Sigle, Gavin W. (19 September 2013). "Bowel Preparation before Elective Surgery". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 26 (3): 146–152. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1351129. PMC 3747288. PMID 24436665.

- "Colyte/Trilyte Colonoscopy Preparation" (PDF). Palo Alto Medical Foundation. June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- Bretthauer, M; Hoff G; Severinsen H; Erga J; Sugar J; Huppertz-Hauss G (20 May 2004). "[Systematic quality control programme for colonoscopy in an endoscopy centre in Norway]". Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening (in Norwegian). 124 (10): 1402–5. PMID 15195182.

- Rikshospitalet University Hospital (April 2006). "Clinical Trial: Nitrous Oxide for Analgesia During Colonoscopy". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- Forbes, GM; Collins BJ (March 2000). "Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy: a randomized controlled study". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 51 (3): 271–7. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(00)70354-3. PMID 10699770.

- Clarke, Anthony C; Louise Chiragakis; Lybus C Hillman; Graham L Kaye (18 February 2002). "Sedation for endoscopy: the safe use of propofol by general practitioner sedationists". Medical Journal of Australia. 176 (4): 158–161. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04345.x. PMID 11913915. S2CID 24387384.

- Bechtold, ML.; Puli, SR.; Othman, MO.; Bartalos, CR.; Marshall, JB.; Roy, PK. (Jan 2009). "Effect of music on patients undergoing colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Dig Dis Sci. 54 (1): 19–24. doi:10.1007/s10620-008-0312-0. PMID 18483858. S2CID 2403242.

- "- YouTube". www.youtube.com.

- Brown SR; Baraza W; Din S; Riley S (2016). "Chromoscopy versus conventional endoscopy for the detection of polyps in the colon and rectum". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (4): CD006439. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006439.pub4. PMC 8749964. PMID 27056645.

- Lichtenstein, Gary R.; Peter D. Park; William B. Long; Gregory G. Ginsberg; Michael L. Kochman (18 August 1998). "Use of a Push Enteroscope Improves Ability to Perform Total Colonoscopy in Previously Unsuccessful Attempts at Colonoscopy in Adult Patients". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 94 (1): 187–90. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00794.x. PMID 9934753. S2CID 24536782. Note:Single use PDF copy provided free by Blackwell Publishing for purposes of Wikipedia content enrichment.

- Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, et al. (2006). "Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy". New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (24): 2533–41. doi:10.1056/nejmoa055498. PMID 17167136.

- "Our Second Brain: The Stomach". May 1999. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- Zhang, Kaixian; Yuan, Qianqian; Zhu, Shuguang; Xu, Daheng; An, Zhe (2018). "Is Unsedated Colonoscopy Gaining Ground Over Sedated Colonoscopy?". Journal of the National Medical Association. 110 (2): 143–148. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2016.12.003. ISSN 0027-9684. PMID 29580447.

- Njemanze PC, Njemanze J, Skelton A, et al. (July 2008). "High-frequency ultrasound imaging of the duodenum and colon in patients with symptomatic giardiasis in comparison to amebiasis and healthy subjects". J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 23 (7 Pt 2): e34–42. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05056.x. PMID 17645477. S2CID 25370999.

- Zauber AG (2010). "Cost-effectiveness of colonoscopy". Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 20 (4): 751–70. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2010.07.008. PMC 4145837. PMID 20889076.

- Wolff WI. (September 1989). "Colonoscopy: History and development". Am J Gastroenterol. 84 (9): 1017–25. PMID 2672788.

- Wolff WI, Shinya H (September 1974). "Earlier diagnosis of cancer of the colon through colonic endoscopy (colonoscopy)". Cancer. 34 (Supplement S3): 912–931. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197409)34:3+<912::AID-CNCR2820340720>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 4851470. S2CID 27860224.

- Dorland, W. A. N. & Miller, E.C.L. (1948). The American illustrated medical dictionary. (21st edition). Philadelphia/London: W.B. Saunders Company.

- Dirckx, J.H. (Ed.) (1997).Stedman's concise medical dictionary for the health professions. (3rd edition). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- Anderson, D.M. (2000). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (29th edition). Philadelphia/London/Toronto/Montreal/Sydney/Tokyo: W.B. Saunders Company.

- Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Anastassiades CP, Cremonini F, Hadjinicolaou D (2008). "Colonoscopy and colonography: back to the roots". Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 12 (6): 345–7. PMID 19146195.

- Foster, F.D. (1891-1893). An illustrated medical dictionary. Being a dictionary of the technical terms used by writers on medicine and the collateral sciences, in the Latin, English, French, and German languages. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Further reading

- Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, et al. (March 2020). "Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". Gastroenterology. 158 (4): 1131–1153.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.026. PMC 7672705. PMID 32044092.

- Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, et al. (March 2020). "Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer". Am J Gastroenterol. 115 (3): 415–434. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000544. PMC 7393611. PMID 32039982.

External links

- Colonoscopy. Based on public-domain NIH Publication No. 02-4331, dated February 2002.

- Patient Education Brochures. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy information

- Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Screening — United States, 2008 and 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention