Mount Garibaldi

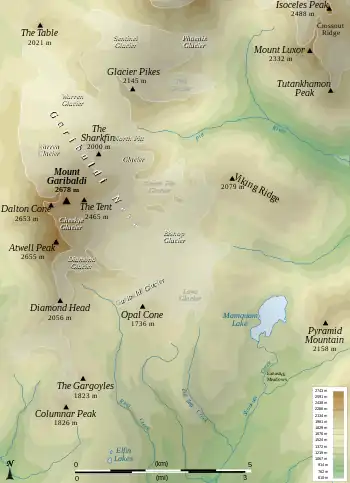

Mount Garibaldi (known as Nch'ḵay̓, IPA: [n̩.ʧʼqɛˀj̰], to the indigenous Squamish people) is a dormant stratovolcano in the Garibaldi Ranges of the Pacific Ranges in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It has a maximum elevation of 2,678 metres (8,786 feet) and rises above the surrounding landscape on the east side of the Cheakamus River in New Westminster Land District. In addition to the main peak, Mount Garibaldi has two named sub-peaks. Atwell Peak is a sharp, conical peak slightly higher than the more rounded peak of Dalton Dome. Both were volcanically active at different times throughout Mount Garibaldi's eruptive history. The northern and eastern flanks of Mount Garibaldi are obscured by the Garibaldi Névé, a large snowfield containing several radiating glaciers. Flowing from the steep western face of Mount Garibaldi is the Cheekye River, a tributary of the Cheakamus River. Opal Cone on the southeastern flank is a small volcanic cone from which a lengthy lava flow descends. The western face is a landslide feature that formed in a series of collapses between 12,800 and 11,500 years ago. These collapses resulted in the formation of a large debris flow deposit that fans out into the Squamish Valley.

| Mount Garibaldi | |

|---|---|

West face of Mount Garibaldi | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,678 m (8,786 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 49°51′01″N 123°00′17″W[2] |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 3 km (1.9 mi)[3] |

| Width | 5 km (3.1 mi)[3] |

| Volume | 6.5 km3 (1.6 cu mi)[3] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Giuseppe Garibaldi[2] |

| Native name | Nch'ḵay̓ (Squamish)[2] |

| Geography | |

Mount Garibaldi Location in British Columbia | |

| Country | Canada[3] |

| Province | British Columbia[3] |

| District | New Westminster Land District[2] |

| Protected area | Garibaldi Provincial Park[4] |

| Parent range | Garibaldi Ranges |

| Topo map | NTS 92G14 Cheakamus River[2] |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | < 260,000 years old[3] |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano[1] |

| Type of rock | Dacite[3] |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Cascade Volcanic Arc[5] Garibaldi Volcanic Belt[3] |

| Last eruption | 8060 BCE ± 500 years[6] |

Mount Garibaldi has been the focus of intermittent volcanic activity over the last 260,000 years. This activity produced mostly dacite, the main type of volcanic rock forming Mount Garibaldi. Volcanism between 260,000 and 220,000 years ago constructed an ancestral cone that was subsequently destroyed. Another growth period began with the eruption of Atwell Peak about 13,000 years ago when Mount Garibaldi was surrounded by an ice sheet during the last glacial period. The latest period of volcanic activity took place about 10,000 years ago with eruptions from Dalton Dome and Opal Cone after the ice sheet retreated. Although the mountain is not known to have been volcanically active since that time, it could erupt again, which could endanger the nearby populace. If this were to happen, relief efforts could be organized by teams such as the Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan who are prepared to notify people threatened by volcanic eruptions in Canada.

The area surrounding Mount Garibaldi has been inhabited by indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Their oral history includes a story of the mountain and a great flood. The non-indigenous name of the mountain was given by George Henry Richards in 1860 in honour of the Italian patriot and soldier Giuseppe Garibaldi. Several mountaineers had climbed Mount Garibaldi by the early 1900s, some of whom were members of mountaineering clubs. A plane operated by Pacific Western Airlines crashed on the slopes of Mount Garibaldi in 1953; all five people aboard were killed. The construction of a ski resort was begun in the late 1960s, but developments were halted in 1969 due to financial difficulties. Several climbing routes ascend the flanks of Mount Garibaldi and involve traversing glaciers, snow slopes or loose rock. Mountain climbing hazards include crevasses, avalanches and rockfalls. Access to Mount Garibaldi is via hiking trails from Alice Ridge, Brohm Ridge, and the Diamond Head parking lot at the end of Garibaldi Park Road.

Geography

Background

Mount Garibaldi is located on the east side of the Cheakamus River between Squamish and Whistler in New Westminster Land District.[2] It lies within the Pacific Ranges Ecoregion, a mountainous region of the southern Coast Mountains characterized by high, steep and rugged mountains made of granitic rocks. Much of this ecoregion encompasses the Pacific Ranges in southwestern British Columbia, although it also includes the northwesternmost portion of the Cascade Range in Washington state. Several coastal islands, channels and fjords occur along the western margin of the Pacific Ranges Ecoregion. The Pacific Ranges Ecoregion is part of the Coast and Mountains Ecoprovince which forms part of the Humid Maritime and Highlands Ecodivision.[7]

The Pacific Ranges Ecoregion is subdivided into seven ecosections, the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection being the main ecosection at Mount Garibaldi. This ecosection is characterized by a rugged landscape of mountains that increase in elevation from south to north; the northern summits contain large icefields. A transitional climate between coastal maritime and interior continental climates dominates the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection. It is characterized by little precipitation and mild temperatures due to air from the Pacific Ocean often passing over this area. During winter, cold Arctic air invades from the Central Interior, resulting in extreme cloud cover and snow. A number of other volcanoes are situated within the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection. This includes Mount Cayley, which lies in the Squamish River watershed, and Mount Meager, which lies near the headwaters of the Lillooet River.[7]

Several rivers flow through the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection, including the Fraser and Coquihalla rivers on its eastern side, the Cheakamus, Squamish and Elaho rivers on its western side and the Lillooet River lying in the middle. Coastal western hemlock forests dominate nearly all the valleys and lower slopes of this ecosection, the upper slopes containing subalpine mountain hemlock forests and, to a lesser extent, Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir forests. Alpine vegetation lies just above the subalpine forests, which is normally overlain by barren rock.[7] Wildlife such as grey jays, chipmunks, squirrels, flickers,[4] Columbian black tailed deer,[8] mountain goats, wolverines, cougars and grizzly and black bears are locally present.[4] The communities of Whistler, Pemberton, Mount Currie, Hope and Yale are situated within the Eastern Pacific Ranges Ecosection, all of which are connected to the Lower Mainland by a network of highways.[7]

Subfeatures

The northern and eastern flanks of Mount Garibaldi are covered by the Garibaldi Névé, the main glacial feature at the volcano.[9][10] Several individually named outlet glaciers drain the Garibaldi Névé.[11] These include Garibaldi Glacier northwest of Opal Cone,[11][12] North Pitt Glacier on the northeastern face of Mount Garibaldi,[11][13] South Pitt Glacier southeast of Glacier Pikes,[11][14] Lava Glacier west of Mamquam Lake,[11][15] Sentinel Glacier southeast of Garibaldi Lake,[11][16] Warren Glacier at the headwaters of Culiton Creek,[11][17] Bishop Glacier south of the head of the Pitt River,[11][18] Phoenix Glacier south of Deception Peak[11][19] and Pike Glacier east of Glacier Pikes.[11][20] The Garibaldi and Lava glaciers issue from the south side of the Garibaldi Névé, sending their muddy waters to the Mamquam River. Immediately to the north of Mount Garibaldi and directly below its northern face, the Warren Glacier flows towards the Cheakamus River.[21] The Garibaldi Névé and its outlet glaciers have a combined area of about 30 square kilometres (12 square miles).[22] Other glaciers on Mount Garibaldi include Cheekye Glacier south of the summit[11][23] and Diamond Glacier between Atwell Peak and Diamond Head.[11][24] Although the glaciers at times have seen surges reaching further down slope, a 2009 study published in the Global and Planetary Change journal found that they overall have been progressively retreating since the early 1900s.[25] A study conducted by the University of British Columbia in 2015 determined that 70% of all the glacial ice in Canada would be melted away by the year 2100. However, observations of the nearby Helm Glacier and other glaciers throughout Canada in 2022 suggest that the 2015 estimate may be an underestimation.[26]

Mount Garibaldi contains a number of individually named peaks. Atwell Peak is a conical plug dome 2,620 metres (8,600 feet) in elevation.[3][11][27] It is named after Atwell Duncan Francis Joseph King, an ardent mountaineer who led the first ascent of Mount Garibaldi in 1907.[2] Atwell Peak contains sharp and exposed ridges, as well as steep and loose faces that are prone to avalanching.[11] Dalton Dome is a 2,633-metre (8,638-foot) blunt summit named after Arthur Tinniswood Dalton.[27][28] Dalton was a Vancouver architect, city assessor and mountaineer who took part in the first ascent of Mount Garibaldi.[28] The eastern side of Mount Garibaldi contains a peak known as The Tent.[29] Opal Cone on the southeastern flank of Mount Garibaldi is a 1,740-metre (5,710-foot) parasitic cone near the south side of Garibaldi Glacier.[1][27][30] A spur known as The Sharkin separates the Warren and North Pitt glaciers on the northeast side of Mount Garibaldi.[31] Diamond Head is a subsidiary peak on the south side of Mount Garibaldi named for its resemblance to Diamond Head in Hawaii.[32][33]

Mount Garibaldi lies within the Squamish River watershed.[7] Its steep western face is the source of the Cheekye River which drains a small but steep catchment on its western flank that covers an area of 60 square kilometres (23 square miles).[34][35] The Cheekye River flows west into the Cheakamus River which flows south and southwest into the Squamish River.[36][37] Cheekye is a Squamish name meaning "strong rushing water".[36] Ring Creek originates from the Bishop and Diamond glaciers on Mount Garibaldi.[38] It flows west and southwest into the Mamquam River which flows west and south into the mouth of the Squamish River.[39][40] Zig Zag Creek drains Lava Glacier and flows southeast into Skookum Creek.[41][42] The Pitt River also originates at Mount Garibaldi and flows southwest from the North Pitt and South Pitt glaciers into the Fraser River.[38][43]

Geology

Mount Garibaldi is one of the three principal volcanoes in the southern segment of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, the other two being Mount Price and The Black Tusk.[3] It represents the largest volcano in the combined Mount Garibaldi–Garibaldi Lake volcanic field, which encompasses 26 cubic kilometres (6.2 cubic miles) of volcanic material.[44] This volcanic field consists of at least twelve eruptive centres that are in the form of stratovolcanoes, lava domes, cinder cones and subglacial volcanoes.[44][45] These include Mount Price, The Black Tusk, The Table, Cinder Cone and Round Mountain, all of which formed in the last 1.3 million years.[45] The Mount Garibaldi–Garibaldi Lake volcanic field is normally separated into the Mount Garibaldi and Garibaldi Lake volcanic fields on the basis of differing magmatic chemistry.[44] The Mount Garibaldi lavas are hypersthene-normative hawaiites and nepheline-normative mugearite with subordinate olivine tholeiites whereas the Garibaldi Lake lavas are calc-alkaline basaltic andesites through rhyolite.[45]

Like other volcanoes in the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, Mount Garibaldi formed as a result of subduction zone volcanism. As the Juan de Fuca Plate thrusts under the North American Plate at the Cascadia subduction zone, it forms volcanoes and volcanic eruptions.[46] Unlike most subduction zones worldwide, there is no deep oceanic trench along the continental margin of Cascadia. There is also very little seismic evidence that the Juan de Fuca Plate is actively subducting. The probable explanation lies in the rate of convergence between the Juan de Fuca and North American plates. These two tectonic plates currently converge at a rate of 3 to 4 centimetres (1.2 to 1.6 inches) per year, only about half the rate of convergence from seven million years ago. This slowed convergence likely accounts for reduced seismicity and the lack of an oceanic trench. The best evidence for ongoing subduction is the existence of active volcanism in the Cascade Volcanic Arc.[3]

Structure

Mount Garibaldi is a moderately eroded stratovolcano overlooking the town of Squamish at the head of Howe Sound north of Vancouver.[1][3][47] It is one of the three Cascade Arc volcanoes made exclusively of dacite, the other two being Glacier Peak and Mount Cayley. Rhyodacite is also a common volcanic rock at Mount Garibaldi and Mount Cayley, although high-silica rhyolite is uniquely present at Mount Garibaldi. Subordinate andesite erupted at all three volcanoes relatively early in their histories. At Mount Garibaldi, the total volume of volcanic rocks amount to 16 to 20 cubic kilometres (3.8 to 4.8 cubic miles) and represent many episodes of activity spanning from about 670,000 years ago to the Holocene. Andesite-dacite lavas and their pyroclastic accompaniments from several vents initially filled paleovalleys glacially incised into the Coast Plutonic Complex basement. Several dacitic domes and derivative pyroclastic material then built the main volcanic edifice starting about 260,000 years ago.[48] Much of the volcano was rebuilt in the last 50,000 years by a series of violent eruptions similar in character to the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée.[49] The modern 6.5-cubic-kilometre (1.6-cubic-mile) volcanic edifice is a supraglacial volcano, having been partially constructed over glacial ice during the Pleistocene epoch.[3][33]

Like many other stratovolcanoes in the Cascade Volcanic Arc, Mount Garibaldi stands out by itself above the surrounding landscape. This is in contrast to most other volcanoes in the Coast Mountains, which are hidden within higher subranges.[11] The mountain has a proximal relief[lower-alpha 1] of 1,300 metres (4,300 feet), a draping relief[lower-alpha 2] of 2,375 metres (7,792 feet), an elevation of 2,678 metres (8,786 feet) and a height of 700 metres (2,300 feet).[3][48] With a length of 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) and a width of 5 kilometres (3.1 miles), Mount Garibaldi is one of the larger volcanoes in the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt.[3] The western side of the mountain contains a 600-metre-high (2,000-foot) scarp exposing its internal structure.[3][5] This scarp formed as a result of collapse of the western flank which produced a debris flow deposit in the Squamish Valley called the Cheekye Fan.[5][50] At the time of its formation, the Cheekye Fan extended across Howe Sound, resulting in the impoundment of a freshwater lake upstream of the fan. The Squamish River subsequently built a delta into this lake during the Holocene. It then filled in the lake with sediment over the last 3,300 years to create the Squamish River floodplain.[50]

Mount Garibaldi is bounded by Brohm Ridge on the northwest and by Alice Ridge on the southwest.[51][52] Extending from the southern flank of Mount Garibaldi is the unusually long Ring Creek lava flow. It is dacitic in composition, attains a length of approximately 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) and contains well-defined levees[lower-alpha 3] along its margins.[49] The emplacement of the Ring Creek lava flow altered drainage patterns along a valley bottom downstream, causing Skookum Creek and the Mamquam River to follow the southern margin of the lava flow and Ring Creek to follow along the northern margin. Sediments eroded from the Ring Creek lava flow form an alluvial fan at the Mamquam River and Skookum Creek confluence.[54] The western slopes of Mount Garibaldi are underlain by sheared and altered quartz diorite, which has undergone stream and glacial erosion to form rugged topography with relief up to 1,800 metres (5,900 feet).[3]

Volcanic history

At least three stages of eruptive activity contributed to the formation of Mount Garibaldi.[55] The initial Cheekye stage took place between 260,000 and 220,000 years ago with the eruption of dacite and breccia, resulting in the formation of a broad composite cone.[45][56] Parts of this "proto-Garibaldi" or ancestral volcano are exposed on Mount Garibaldi's lower northern and eastern flanks and on the upper 240 metres (790 feet) of Brohm Ridge. Around where Columnar Peak and possibly Glacier Pikes are now located, several coalescing dacitic domes were constructed.[56] Dacite from the western end of Alice Ridge, from Columnar Peak and from Mount Garibaldi have K–Ar ages of 260,000 ± 160,000 years, 220,000 ± 220,000 years and 260,000 ± 130,000 years, respectively.[55] During the ensuing long period of dormancy, the Cheekye River cut a deep valley into the cone's western flank which was later filled with the Fraser ice sheet.[45][56]

After reaching its maximum extent, the Fraser ice sheet was covered with volcanic ash and fragmented debris from the Atwell Peak stage.[55][56] This period of growth began about 13,000 years ago with the eruption of the Atwell Peak plug dome from a ridge surrounded by the ice sheet.[3][56] As the plug dome rose, massive sheets of broken lava crumbled as talus down its sides. Several pyroclastic flows generated by Peléan eruptions accompanied these cooler avalanches, forming a fragmental cone with an overall slope of 12–15 degrees; erosion has since steepened this slope. Some of the glacial ice was melted by the eruptions, forming a small lake against Brohm Ridge's southern arm. The volcanic sandstones seen today atop Brohm Ridge were created by ash settling in this lake.[56]

Glacial overlap was most significant on the west and somewhat to the south.[56] Subsequent melting of the ice sheet and its component glaciers removed support from the western flank of Mount Garibaldi, resulting in a series of landslides between 12,800 and 11,500 years ago that moved nearly half of the volcano's volume into the Squamish Valley.[50][56][57] This catastrophic collapse produced the 25-square-kilometre (9.7-square-mile) Cheekye Fan and the scarp exposing the internal structure of Mount Garibaldi.[57][58] Soon before or after the buried ice had melted away, the Dalton Dome stage commenced with the eruption of dacite lava down Mount Garibaldi's north and northeastern flanks.[56] Another dacite flow issued from Dalton Dome shortly after the ice sheet had receded, having travelled down the landslide scarp on Mount Garibaldi's western flank.[3][56] Possibly contemporaneous volcanism occurred at Opal Cone with the eruption of the voluminous Ring Creek lava flow between 10,700 and 9,300 years ago.[3][57] This represents the latest known eruptive event at Mount Garibaldi and the volcano is now considered to be dormant.[3][54][59][60]

At least two debris flows in the order of 100,000 cubic metres (3,500,000 cubic feet) occurred at Mount Garibaldi in the 1930s and 1950s, both of which swept down the Cheekye River. The 1950s debris flow was caused by heavy rains and reached the Cheakamus River where it formed a 5-metre-high (16-foot) temporary landslide dam.[61] This is the latest debris flow to reach the Cheakamus River from the Cheekye basin.[62] In contrast to Mount Cayley and Mount Meager, no hot springs are known in the Garibaldi area. However, there is evidence of anomalously high heat flow in Table Meadows and elsewhere.[63] At least three seismic events have occurred at Mount Garibaldi since 1985, indicating that the volcano is potentially active and poses a significant hazard to the area.[64]

Volcanic hazards

.jpg.webp)

Mount Garibaldi is one of two volcanoes in Canada classified as a very high threat by Natural Resources Canada, the other volcano being Mount Meager 95 kilometres (59 miles) to the northwest.[65] Although Plinian eruptions have not been identified at Mount Garibaldi, Peléan eruptions can also produce large amounts of volcanic ash that could significantly affect the nearby communities of Whistler and Squamish. Peléan eruptions might cause short and long term water supply problems for the city of Vancouver and most of the Lower Mainland. The catchment area for the Greater Vancouver watershed is downwind from Mount Garibaldi. An eruption producing floods and lahars could destroy parts of Highway 99, threaten communities such as Brackendale and endanger water supplies from Pitt Lake. Fisheries on the Pitt River would also be at risk.[57] Mount Garibaldi is also close to a major air traffic route; volcanic ash reduces visibility and can cause jet engine failure, as well as damage to other aircraft systems.[66][67] These volcanic hazards become more serious as the Lower Mainland grows in population.[57]

At the head of the Cheekye River are several fractures and linear scarps that face up-slope. These features, referred to as the Cheekye linears, occur in pyroclastic rocks and interbedded andesitic and dacitic flows on the slopes of Brohm and Alice ridges. They may have formed as a result of sliding of this volcanic sequence along its contact with the underlying basement rocks.[68] As a result, the Cheekye linears pose potential landslide hazards to Brackendale and several Squamish Nation villages nearby.[68][69] The danger of catastrophic landslides from Mount Garibaldi has restricted development on the Cheekye Fan.[68] In 2018, a major development on the Cheekye Fan was approved by Squamish council. The project included 537 single-family units, 678 multi-unit dwellings and a $45 million debris flow barrier to prevent a large landslide from reaching the Cheekye Fan.[69]

Because dacite is the main type of lava erupted from Mount Garibaldi, lava flows are a low to moderate hazard.[3] Dacite is felsic[lower-alpha 4] in composition, containing 62–69% silica content.[71][72] This high percentage in silica content increases the viscosity of dacitic melts relative to that of andesite or basalt, generally resulting in the formation of steep-sided lava domes and stubby lava flows.[73][74] An exception is the 15-kilometre-long (9.3-mile) Ring Creek dacite flow from Opal Cone, a length that is normally attained by basaltic lava flows.[57]

Monitoring

Like other volcanoes in Canada, Mount Garibaldi is not monitored closely enough by the Geological Survey of Canada to ascertain its activity level. The Canadian National Seismograph Network has been established to monitor earthquakes throughout Canada, but it is too far away to provide an accurate indication of activity under the mountain. It may sense an increase in seismic activity if Mount Garibaldi becomes highly restless, but this may only provide a warning for a large eruption; the system might detect activity only once the volcano has started erupting.[75] If Mount Garibaldi were to erupt, mechanisms exist to orchestrate relief efforts. The Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan was created to outline the notification procedure of some of the main agencies that would respond to an erupting volcano in Canada, an eruption close to the Canada–United States border or any eruption that would affect Canada.[76]

Human history

Indigenous peoples

To the Squamish people, the local indigenous people of this area, Mount Garibaldi is called Nch'ḵay̓ (in-ch-KAI). In their language it means "Dirty Place", referring to the muddy waters of the Cheekye River. Mount Garibaldi is considered sacred to the Squamish people as it is an important part of their history. In their oral history, they passed down a story of the great flood that covered their land after the last ice age.[2] During the flood, Mount Garibaldi was only one of two mountains that peaked over the water.[77] The Squamish people headed for Mount Garibaldi and latched their canoes to the mountain with a rope made from woven cedar bark in order to prevent being swept away.[2][77] As the flood waters started to recede, a large lake was formed and the Squamish people returned to their home site in Squamish.[77]

Mount Garibaldi is the largest volcano in Squamish Nation territory. An obsidian outcrop on the southeastern flank of Mount Garibaldi is said by the Squamish people to have been created by the thunderbird, a legendary creature in some North American indigenous peoples' history and culture. During battles, the thunderbird helped the Squamish people fight against evil by shooting lightning from its eyes and creating powerful winds and thunder with its wings. The obsidian outcrop is where lightning from the thunderbird's eyes struck ground.[77] Garibaldi obsidian was used to create tools due to its ability to form sharp edges, but its quality is poor compared to other obsidian sources in British Columbia. Pieces of Garibaldi obsidian are distributed in the Strait of Georgia where they occur in archaeological sites as early as 4,500 years old.[78]

Later history

Mount Garibaldi was witnessed by George Henry Richards in 1860 while surveying Howe Sound on board the Royal Navy ship HMS Plumper.[4] Richards named the mountain that year after Giuseppe Garibaldi, an Italian patriot and soldier who in 1860 had succeeded in unifying Italy by patriating Sicily and Naples.[2][4][79] The first ascent of Mount Garibaldi was made by Vancouver mountaineers Gordon B. Warren, Arthur Tinniswood Dalton, Tom C. Pattison, William Tinniswood Dalton, James John Trorey and Atwell Duncan King on August 11, 1907.[2][80] This mountaineering party had recognized the volcanic origin of the mountain.[81] Another party led by A. T. Dalton ascended the main peak and dome of Mount Garibaldi by a new and better route in 1908.[82] This was followed by an ascent to the summit in 1910 by members of the Alpine Club of Canada and a local mountaineering club. Party members included A. Morkill, B. S. Darling, A. Cawdry, W. G. Barker, A. J. Armistead and Mr. Wedgwood.[83] A party consisting of 13 members of the British Columbia Mountaineering Club ascended Mount Garibaldi from the southeast face on August 13, 1911.[84] The first women to attain the summit of Mount Garibaldi were Vancouver climbers Pansy Munday and L. C. Hanafin on July 16, 1913.[85] They ascended the west face of Mount Garibaldi by approaching from the southwest, which involved traversing along the Mamquam River and then climbing Round Mountain and The Gargoyles.[86] Hanafin and Munday also climbed neighbouring Mamquam Mountain during the same expedition.[85]

.jpg.webp)

The first United States party to climb Mount Garibaldi consisted of 13 members of The Mountaineers in August 1923. It included Norman Huber of Saint Paul, Minnesota; Paul Hugdahl, Paul Gooding and C. A. Fisher of Bellingham, Washington; C. A. Garner, Amos Hard and A. H. Denman of Tacoma, Washington; Edmond S. Meany, George Hise, Lars Loveseth, Ben F. Mooers, Joseph T. Hazard and Fred Fenton of Seattle, Washington.[87] The leader of the climbing party, Joseph T. Hazard, stated that "while a little less than 9,000 feet high, Mount Garibaldi is much more difficult of ascent than any of the major peaks of Washington".[87][88] In 1927, Mount Garibaldi was incorporated into the newly formed, 195,000-hectare (480,000-acre) Garibaldi Provincial Park.[4] This mountainous Class A provincial park was named after Mount Garibaldi and contains a number of other volcanoes, including Mount Price, Cinder Cone, The Black Tusk and The Table.[4][89] Despite being the namesake of Garibaldi Provincial Park, Mount Garibaldi is not its highest mountain.[11]

On October 19, 1953, a plane operated by Pacific Western Airlines crashed on the slopes of Mount Garibaldi, killing all five people aboard. The plane was on a mercy flight from Gunn Lake to Vancouver at the time of the accident. Passengers involved in the crash were Lawrence Hamilton of the Pioneer mines, Ernest Maple of Gold Bridge, nurse Lucille Warden, pilot Bob Drinkwater and stretcher passenger Joseph Neumeyer, the latter being an injured miner who was being rushed to a hospital in Vancouver. The smashed plane and deceased passengers were found by a ground search party on October 20. This was followed by removal of the passengers from the wreckage on October 21. Post-accident investigation could not determine the cause of the crash.[90]

Vancouver teachers Christopher Clifford Harris, 33, and Margo Anne Fowler, 26, got married on the summit of Mount Garibaldi on April 14, 1973, to express their passion for mountain climbing. The couple managed to get to the nearly inaccessible, 12-by-30-metre (39-by-98-foot) summit by helicopter. They wore traditional mountaineering garb for their wedding. According to Harris, "You can see snow and mountain tops forever. Even Mount Baker, and that's 100 miles away."[91]

Ski resort development

A multi-million dollar ski resort, Mount Garibaldi Glacier Resorts, was to be built on Brohm Ridge in the late 1960s.[92][93] It was designed by West Vancouver resident Adi Bauer in 1954 to feature a luxury lodge, three Swiss-style chalets and the world's longest gondola lift. Access to the ski resort was to be by helicopter or snowshoes in winter, although a rough road winding up the ridge to the ski resort lodge was to provide four-wheel drive access in summer. The ski resort was to open in the winter of 1970, but financial difficulties in 1969 halted all developments. In January 1970, the three Swiss-style chalets remained unfinished, the gondola lift consisted only of towers with no lift cables, and the gondola cars were stored in another building at the foot of Mount Garibaldi.[92]

In 1978, the Government of British Columbia invited California-based developer Wolfgang Richter to salvage the failed Mount Garibaldi Glacier Resorts project. Richter's plans were postponed by the early 1980s recession and his proposal was denied by the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks in 1991, saying it "did not make economic sense". The ski resort proposed by Richter would have operated as a day-use area and would have featured an almost 1,000-metre-high (3,300-foot) vertical drop. Such a drop would have been greater than those of the Cypress, Manning and Mount Seymour provincial park ski resorts, but still 600 metres (2,000 feet) shorter than the one in Whistler Blackcomb. A total of 15,000 skiers would have been spread across 400 hectares (990 acres) of skiable terrain per day. Accommodation would have been provided by a mid-mountain village and an upper village at elevations of 1,100 and 1,300 metres (3,600 and 4,300 feet), respectively.[93]

Recreation facilities

Overlooking the Tantalus Range is the Brohm Ridge Chalet, a three-story European-style lodge built in the 1960s as part of the attempted ski resort development.[94] It is now operated by the Black Tusk Snowmobile Club, a non-profit organization founded in 1971 in the community of Squamish.[94][95] The Brohm Ridge Chalet sleeps a total of 40 people whilst the nearby Black Tusk Snowmobile Clubhouse sleeps a further 14.[95]

A BC Parks shelter at the Elfin Lakes offers overnight stays and can sleep up to 33 people. It is equipped with a propane heater, a wash sink, pit toilet facilities, propane lights, two propane hot plates and four picnic tables. The Elfin Lakes Campground offers a day-use shelter, hang storage facilities, pit toilet facilities, two outdoor picnic tables, four indoor picnic tables and 35 tent platforms.[96]

The Rampart Ponds Campground, located 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) northeast of the Elfin Lakes shelter, offers food storage facilities, pit toilet facilities and 12 tent platforms.[96]

Accessibility

Mamquam Road, 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) north of downtown Squamish, provides access to Mount Garibaldi from Highway 99. This easterly paved road traverses the Squamish Golf and Country Club and then heads north through Quest University. Mamquam Road then extends northeast and becomes Garibaldi Park Road.[96] At the end of Garibaldi Park Road is the Diamond Head parking lot, which lies 16 kilometres (9.9 miles) from Highway 99 at an elevation of 914 metres (2,999 feet). The 11-kilometre-long (6.8-mile) Diamond Head hiking trail commences from the parking lot to the Elfin Lakes where Opal Cone, Columnar Peak, The Gargoyles and Mamquam Icefield can be viewed.[94][96] A 6.5-kilometre-long (4.0-mile) hiking trail extending from the Elfin Lakes leads down to Ring Creek then climbs Opal Cone where Mamquam Lake and the Garibaldi Névé can be viewed from its summit.[96] The route to the Garibaldi Névé on Mount Garibaldi's eastern flank is marked by cairns.[11]

An alternative approach to Mount Garibaldi is via Alice Ridge, which can be accessed from Highway 99 to Alice Lake Provincial Park where jeep roads switchback up onto the ridge. The saddle dividing Diamond Head and The Gargoyles is then traversed northeasterly on a trail to the Garibaldi Névé. It is also possible to access Mount Garibaldi from Brohm Ridge. An unmarked road just before Brohm Lake and north of the Alice Lake Provincial Park turnoff extends southward from Highway 99 towards Cat Lake. About 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) down the road is a gate that is locked at 5 p.m. on Friday evenings and not reopened until Sunday evenings. After the gate has been passed, the road heads eastward and switchbacks up the southwestern slope of Brohm Ridge. It then passes the abandoned ski area on top of the ridge before terminating. From the road's end, Brohm Ridge is hiked to the Garibaldi Névé.[11]

Climbing and skiing

Mountain climbing on Mount Garibaldi is done in winter when the loose volcanic rocks comprising the mountain are frozen in place by snow and ice. Most climbing routes are confined to the glaciers and snow slopes, which are abundant in winter and spring. They require climbers to possess some level of climbing skill; their grades and classes range from II-to-V and 2-to-5 on the Yosemite Decimal System, respectively. Ski camping on the Garibaldi Névé is common in winter, but high winds are not unusual. Therefore, most winter skiers and climbers wisely protect campsites by digging into the snow or constructing snow walls or igloos for shelter.[11]

The Garibaldi Névé is a common ski destination, particularly in spring, and provides open access to many of the climbing routes. In later season, skiing across the névé is possible, but not much easier than walking. Skis are rarely used by June or July when most ascents are made. The glaciers and snow slopes of Mount Garibaldi become boggy and then normally melt away after June or July in most years. In contrast, the Garibaldi Névé provides open access to several climbing routes until late summer.[11]

Dangers and accidents

Bergschrunds and other crevasses can pose difficulty and danger in late spring or summer when snow and ice has melted away. Rockfalls and loose rock are ever-present hazards at this time of the year; rocks regularly rumble down Mount Garibaldi's flanks without apparent provocation. For this reason, early-season, cold-weather snow ascents are recommended for most routes up Mount Garibaldi. However, at least some of these routes can have high avalanche danger in winter and spring, making rockfalls and avalanches ever-present hazards throughout the year.[11]

In April 1950, Vancouver photographer Otto E. Landauer fractured a leg when a ski broke while skiing on Mount Garibaldi.[97][98] It was Landauer's first accident as an expert skier, having occurred as the 46-year-old neared Diamond Head Lodge. Landauer was brought down Mount Garibaldi by a party of 25 holidayers at Diamond Head Lodge and then transferred to a light truck which took him to Squamish via logging road. The 46-hour rescue operation ended on April 11 when a speedboat waiting at Squamish brought Landauer to St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver.[99]

Frank de Bruyn, a 16-year-old mountain climber from Vancouver, was killed by a small avalanche near the snow-covered summit of Mount Garibaldi on July 19, 1961. De Bruyn was one of three youths climbing Mount Garibaldi, the other two being 18-year-olds James Hebden and James Fowler. Hebden got caught in the edge of the avalanche and was sent to the Squamish General Hospital after sustaining a lung injury. Fowler escaped injury, but underwent shock treatment the next day after stumbling down the mountainside with word of the accident.[100]

Vancouver mountaineers Lloyd Williams, 26, Heinz Rostek, 22, and Don Hoover, 22, were trapped on Mount Garibaldi for four days in April 1963. The trio left the Diamond Head chalet on April 11 for a 19-kilometre-long (12-mile) skiing trip around Mount Garibaldi to Garibaldi Lake where they were to meet another group of skiers on April 14. They became trapped by a blizzard on the 2,300-metre (7,500-foot) level of Mount Garibaldi on April 13 where the three men set up a camp. The trio remained at the camp until April 17 when the weather cleared. Fresh ski marks left by the three mountaineers were spotted that morning by ground searchers and a Royal Canadian Air Force helicopter found the trio at noon.[101]

Garibaldi Peak routes

| Class | Summary |

|---|---|

| 2 | Simple scrambling, with the possibility of occasional use of the hands. |

| 3 | Scrambling with increased exposure. A rope could be carried. |

| 4 | Simple climbing, possibly with exposure. A rope is often used. |

| 5 | Technical roped free climbing; belaying is used for safety. |

| Grade | Duration |

| II | Less than half a day |

| III | Half a day climb |

| IV | Full day climb |

| V | A climb lasting 2–3 days |

The normal route up Mount Garibaldi is the East Face Route (grade II and class 3–4). It is normally approached via Garibaldi Névé or Elfin Lakes, although it can also be approached via Alice Ridge. This route crosses the Garibaldi Névé and ascends toward the Garibaldi–Atwell saddle west of The Tent where crevasses in the icefall can sometimes make traversing difficult. There is also the danger of avalanches during ripe snow conditions. A more common and less crevassed approach is via Diamond Glacier to a saddle in the moraine ridge at the foot of Atwell Peak's southeast buttress. Once the saddle has been climbed by ascending a final steep slope, the rocky summit of Mount Garibaldi is reached by proceeding up Cheekye Glacier.[11]

The Northeast Face Route (grade II and class 3–4) is a straightforward glacier ascent crossing the Warren Glacier. It ascends moderate snow and glacier slopes of the northeast face then approaches the headwall where a bergschrund is crossed with potential difficulty. Broken rock or snow is then ascended to the summit. This route is often traversed on skis by parties travelling over the Garibaldi Névé. The area below the summit pinnacle is exposed to rockfall and is moderately prone to avalanching.[11]

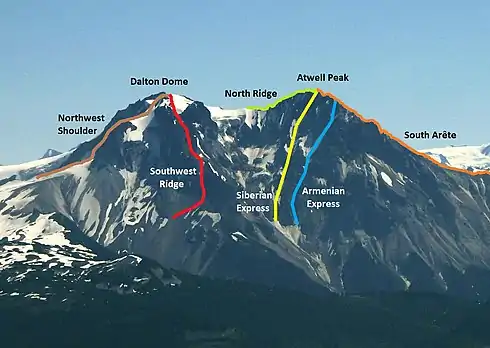

Atwell Peak routes

Two considerably more challenging and objectively dangerous routes run up the northwest face of Atwell Peak. The first route, referred to as the Armenian Express (grade V and class 4–5), involves climbing the major couloir on the far right of the northwest face. This couloir is ascended until loose rock forces a traverse onto the south ridge just below the summit. The second route is the Siberian Express (grade V and class 4–5) and ascends the huge central couloir just north of the summit of Atwell Peak. It leads directly to the summit ridge over moderately sloping snow and ice with a very steep finish. Both the Armenian and Siberian expresses are exposed to rockfall and have high avalanche danger. For this reason, these routes are mainly climbed in winter when they are well-frozen and contain stable snow.[11]

The normal route up Atwell Peak is the North Ridge Route (grade III and class 4–5). It is a straightforward ascent up the short, exposed and shattered ridge to Atwell's summit from the Garibaldi–Atwell saddle, which can be reached via the East Face Route. The north ridge is alpine in character, featuring steep slopes and very loose rock. Ascents are commonly made in winter when hazards such as avalanches and snow cornices exist all along the ridge.[11]

The South Arête Route (grade IV and class 4–5) is a technical climbing route ascending a highly exposed arête that divides the southeast and southwest faces of Atwell Peak. It leads directly to Atwell's summit, climbing steep terrain throughout its entirety. The route is generally ascended during winter when in optimal condition. Hazards include snow cornices as well as unprotected climbing on loose rock and rime ice.[11]

The Southeast Face Routes (grade II and class 3–4) are approached via Alice Ridge or Elfin Lakes to Diamond Glacier. They ascend couloirs in steep shattered rock, one of which offers a direct climb to a point immediately south of Atwell's summit. The routes offer a straightforward snow and ice climb in winter when the couloirs are covered with stable snow and iced over with rocks frozen in place. Hazards include snow cornices lining the summit ridge in winter, as well as avalanches and rockfalls in less than optimal conditions.[11]

Dalton Dome routes

At least three routes run up Mount Garibaldi to Dalton Dome, none of which are commonly climbed due to extremely poor quality rock. The most direct independent summit route to Dalton Dome is the Northwest Shoulder Route (grade II and class 4), which is approached via Brohm Ridge to the base of Mount Garibaldi's northwest shoulder. It involves climbing snow or loose rock up the shoulder to the summit ridge.[11]

The Southwest Ridge Route (grade III and class 3–4) is mainly climbed in winter when conditions are favorable. It is approached via a snow or scree traverse from Brohm Ridge below the west face of Mount Garibaldi where the southwest ridge is ascended to the summit.[11]

Ascending the Warren Glacier headwall on the far right side is the North Face Route (grade III and class 4–5). It climbs steep snow and remarkably unstable rock to a small escarpment that gains the northwest shoulder, which then leads to Dalton Dome's summit.[11]

See also

Notes

- According to Hildreth's definitions, proximal relief refers to the difference between the summit elevation and the highest exposure of old rocks under the main edifice.[48]

- According to Hildreth's definitions, draping relief marks the difference between the summit elevation and the edifice's lowest distal lava flows (excluding pyroclastic and debris flows).[48]

- Levees are natural embankments that form as a result of periodic overflow of lava or as molten lava pushes cooled lava over the edge of a lava flow.[53]

- Felsic pertains to magmatic rocks that are enriched in silicon, oxygen, aluminum, sodium and potassium.[70]

References

- "Garibaldi: General Information". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- "Mount Garibaldi". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- Wood, Charles A.; Kienle, Jürgen (2001). Volcanoes of North America: United States and Canada. Cambridge University Press. pp. 112, 113, 114, 144, 145. ISBN 0-521-43811-X.

- "Garibaldi Provincial Park". BC Parks. Archived from the original on 2021-07-16. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- Wilson, A. M.; Russell, J. K. (2019). "Quaternary glaciovolcanism in the Canadian Cascade volcanic arc—Paleoenvironmental implications". Field Volcanology: A Tribute to the Distinguished Career of Don Swanson. Vol. 538. Geological Society of America. pp. 134, 141. doi:10.1130/SPE538. ISBN 978-0-8137-9538-6. S2CID 214521258.

- "Garibaldi: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- Demarchi, Dennis A. (2011). An Introduction to the Ecoregions of British Columbia (PDF). Government of British Columbia. pp. 24, 25, 37, 38, 39, 47, 56, 113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- "Garibaldi Provincial Park: 2010 Olympic Venue" (PDF). BC Parks. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- "Garibaldi Névé". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- Ferrigno, Jane G.; Williams, Richard S. (2002). Satellite Image Atlas of Glaciers of the World: North America. United States Government Publishing Office. p. J296. doi:10.3133/pp1386J. ISBN 0-607-98290-X. S2CID 2525336.

- Smoot, Jeff (2012). "Mount Garibaldi". Best Climbs Cascade Volcanoes. FalconGuides. pp. 31–44. ISBN 978-0-7627-7796-9.

- "Garibaldi Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- "North Pitt Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- "South Pitt Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- "Lava Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- "Sentinel Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- "Warren Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- "Bishop Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- "Phoenix Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- "Pike Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- Gray, W. J.; Samson, H. (1913). "The Garibaldi Group". The Northern Cordilleran. British Columbia Mountaineering Club. pp. 25, 26.

- Denton, George H. (1975). "Coast Mountains (Pacific Ranges and Cascade Mountains) and Coast Ranges of British Columbia". Mountain Glaciers of the Northern Hemisphere (Report). Vol. 1. American Geophysical Society. p. 675.

- "Cheekye Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- "Diamond Glacier". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- Koch, Johannes; Menounos, Brian; Clague, John J. (2009). "Glacier change in Garibaldi Provincial Park, southern Coast Mountains, British Columbia, since the Little Ice Age". Global and Planetary Change. Elsevier. 66 (3): 161–178. Bibcode:2009GPC....66..161K. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2008.11.006. ISSN 0921-8181.

- Crawford, Tiffany (2022). "Scientists to hike B.C.'s Helm Glacier in Garibaldi Park to measure glacial melt, effects of climate change". Vancouver Sun. Postmedia Network. Retrieved 2022-10-05.

- "Garibaldi: Synonyms & Subfeatures". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- "Dalton Dome". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- "The Tent". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2021-08-16. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- "Opal Cone". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- "The Sharkfin". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2021-08-15. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- "Diamond Head". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- Mathews, W. H. (1952). "Mount Garibaldi, a supraglacial Pleistocene volcano in southwestern British Columbia". American Journal of Science. American Journal of Science. 250 (2): 81–103. Bibcode:1952AmJS..250...81M. doi:10.2475/ajs.250.2.81.

- Shroder, John F.; Davies, Tim (2015). Landslide Hazards, Risks, and Disasters. Hazards and Disasters. Elsevier. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-12-396452-6.

- Davies, Tim R.; Korup, Oliver; Clague, John J. (2021). "The Scope of Geomorphology in Dealing with Natural Risks and Disasters". Geomorphology and Natural Hazards: Understanding Landscape Change for Disaster Mitigation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 498. ISBN 9781119990314.

- "Cheekye River". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- "Cheakamus River". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2020-07-11. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- "Toporama". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 12 September 2016. Retrieved 2022-08-05.

- "Ring Creek". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- "Mamquam River". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2018-02-18. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- Christie, Jack (2009). The Whistler Book: An All-season Outdoor Guide. Greystone Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-55365-447-6.

- "Zig Zag Creek". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- Dashgard, Shahin; Ward, Brent (2014). "Holocene human interaction and adaptation to geological and climatic changes in the Lower Mainland, Fraser Canyon, and Coast Mountain area of British Columbia: A geoarchaeological view". Trials and Tribulations of Life on an Active Subduction Zone: Field Trips in and around Vancouver, Canada. Geological Society of America. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8137-0038-0.

- Hickson, C. J. (1994). "Character of volcanism, volcanic hazards, and risk, northern end of the Cascade magmatic arc, British Columbia and Washington State". Geology and Geological Hazards of the Vanvouver Region, Southwestern British Columbia. Natural Resources Canada. pp. 239, 240. ISBN 0-660-15784-5.

- Read, Peter B. (1990). "Late Cenozoic Volcanism in the Mount Garibaldi and Garibaldi Lake Volcanic Fields, Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, Southwestern British Columbia". Articles. Geological Association of Canada. 17 (3): 171, 172, 173. ISSN 1911-4850.

- "Garibaldi volcanic belt". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. 2009-04-02. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved 2011-01-21.

- Knight, J.; Harrison, S. (2009). Periglacial and Paraglacial Processes and Environments. Geological Society of London. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-86239-281-6.

- Hildreth, Wes (2007). Quaternary Magmatism in the Cascades—Geologic Perspectives. United States Geological Survey. pp. 7, 8, 10, 11. ISBN 978-1-4113-1945-5.

- Edwards, Ben (2000). "Mt. Garibaldi, SW British Columbia, Canada". VolcanoWorld. Oregon State University. Archived from the original on 2010-07-31. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- Fath, Jared; Clague, John J.; Friele, Pierre (2018). "Influence of a large debris flow fan on the late Holocene evolution of Squamish River, southwest British Columbia, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. NRC Research Press. 55 (4): 333. Bibcode:2018CaJES..55..331F. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0150. hdl:1807/82572. ISSN 1480-3313.

- "Brohm Ridge". BC Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- "Alice Ridge". BC Geographical Names. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- "Kīlauea Volcano — Lava Levees". United States Geological Survey. 2018-07-05. Archived from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- Brooks, Gregory R.; Friele, Pierre (1992). "Bracketing ages for the formation of the Ring Creek lava flow, Mount Garibaldi volcanic field, southwestern British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. NRC Research Press. 29 (11): 2425, 2426. Bibcode:1992CaJES..29.2425B. doi:10.1139/e92-190. ISSN 1480-3313.

- Green, Nathan L.; Armstrong, Richard L.; Harakal, J. E.; Souther, J. G.; Read, Peter B. (1988). "Eruptive history and K-Ar geochronology of the late Cenozoic Garibaldi volcanic belt, southwestern British Columbia". Geological Society of America Bulletin. Geological Society of America. 100 (4): 566. Bibcode:1988GSAB..100..563G. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1988)100<0563:EHAKAG>2.3.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1988). Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes. Mountain Press Publishing Company. pp. 283–288. ISBN 0-87842-220-X.

- "Garibaldi volcanic belt: Garibaldi Lake volcanic field". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. 2009-04-01. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- Friele, Pierre A.; Ekes, C.; Hickin, E. J. (1999). "Evolution of Cheekye fan, Squamish, British Columbia: Holocene sedimentation and implications for hazard assessment". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. NRC Research Press. 36 (12): 2023. doi:10.1139/e99-090. ISSN 1480-3313.

- Morison, Conner (2019). "Volcanic Hazards in the Sea-to-Sky Corridor, BC Canada" (PDF). The Irvine Atlas. University of St Andrews. 1 (1): 6.

- Jakob, M.; Friele, P. (2010). "Frequency and magnitude of debris flows on Cheekye River, British Columbia". Geomorphology. Elsevier. 114 (3): 382–395. Bibcode:2010Geomo.114..382J. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.08.013. ISSN 0169-555X.

- Evans, S.G.; Savigny, K.W. (1994). "Landslides in the Vancouver-Fraser Valley-Whistler region". Geology and Geological Hazards of the Vancouver Region, Southwestern British Columbia. Natural Resources Canada. p. 267. ISBN 0-660-15784-5.

- Clague, John J.; Turner, Robert J. W.; Reyes, Alberto V. (2003). "Record of recent river channel instability, Cheakamus Valley, British Columbia". Geomorphology. Elsevier. 53 (3): 322. Bibcode:2003Geomo..53..317C. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(02)00321-5. ISSN 0169-555X.

- Woodsworth, Glenn J. (April 2003). Geology and Geothermal Potential of the AWA Claim Group, Squamish, British Columbia (PDF) (Report). Government of British Columbia. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-01-09.

- Stasiuk, Mark V.; Hickson, Catherine J.; Mulder, Taimi (2003). "The Vulnerability of Canada to Volcanic Hazards". Natural Hazards. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 28 (2/3): 569. doi:10.1023/A:1022954829974. ISSN 0921-030X. S2CID 129461798.

- Wilson, Alexander M.; Kelman, Melanie C. (2021). Assessing the relative threats from Canadian volcanoes (Report). Geological Survey of Canada Open File 8790. Natural Resources Canada. pp. 32, 34, 50. doi:10.4095/328950.

- "Volcanic hazards". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2009-04-02. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- Neal, Christina A.; Casadevall, Thomas J.; Miller, Thomas P.; Hendley II, James W.; Stauffer, Peter H. (2004-10-14). "Volcanic Ash–Danger to Aircraft in the North Pacific". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2021-07-18. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- Clague, John J.; Friele, Pierre; Hutchinson, Ian (2003). "Chronology and Hazards of Large Debris Flows in the Cheekye River Basin, British Columbia, Canada". Environmental & Engineering Geoscience. Association of Environmental & Engineering Geologists. 9 (2): 100, 101. Bibcode:2003EEGeo...9...99C. doi:10.2113/9.2.99. ISSN 1558-9161.

- Ritchie, Haley (2018). "Huge Squamish mixed-use development takes next step". Vancouver Is Awesome. Glacier Media. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- Pinti, Daniele (2011), "Mafic and Felsic", Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, p. 938, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11274-4_1893, ISBN 978-3-642-11271-3

- Tran, Trong-Hoa; Polyakov, Gleb V.; Tran, Tuan-Anh; Borisenko, Alexander S.; Izokh, Andrey E.; Balkin, Pavel A.; Ngo, Thi-Phuong; Pham, Thi-Dung (2016). Intraplate Magmatism and Metallogeny of North Vietnam. Modern Approaches in Solid Earth Sciences. Springer International Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 978-3-319-25233-9.

- "Volcano Hazards Program Glossary". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2022-04-11.

- "Lava flows destroy everything in their path". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2021-07-05.

- Gill, Robin (2010). Igneous Rocks and Process: A Practical Guide. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-632-06377-2.

- "Monitoring volcanoes". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2009-02-26. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- "Interagency Volcanic Event Notification Plan (IVENP)". Volcanoes of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2008-06-04. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- Reimer, Rudy (2018). "The Social Importance of Volcanic Peaks for the Indigenous Peoples of British Columbia". Journal of Northwest Anthropology. Northwest Anthropology LLC. 52 (1): 6, 9, 11, 13. ISBN 978-1977908285.

- Reimer, Rudy (2000). "The Garibaldi Obsidian Industry at the Marpole Site (DgRs 1)". The Midden. Archaeological Society of British Columbia. 32 (1): 7, 8, 9. ISSN 0047-7222.

- Akrigg, G. P. V.; Akrigg, Helen B. (1997). British Columbia Place Names. University of British Columbia Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-7748-0637-0.

- Stelling, Pete; S. Tucker, David (2007). Floods, Faults, and Fire: Geological Field Trips in Washington State and Southwest British Columbia. Geological Society of America. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8137-0009-0.

- Burwash, Edward M. (1914). "Pleistocene Vulcanism of the Coast Range of British Columbia". The Journal of Geology. University of Chicago Press. 22 (3): 260. Bibcode:1914JG.....22..260B. doi:10.1086/622148. S2CID 128978632.

- "Conquered Garibaldi After Battling With Blizzard". The Province. 1908-08-06. p. 10. Retrieved 2022-07-25 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Scaled Mount Garibaldi". The Province. 1910-09-07. p. 1. Retrieved 2022-07-25 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mount Garibaldi". Saturday Sunset. 1911-09-16. p. 5. Retrieved 2022-07-25 – via Newspapers.com.

- "From Province files". The Province. 1963-07-27. p. 4. Retrieved 2022-07-26 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bridge, Kathryn (2006). The Lives of Don and Phyllis Munday: A Passion for Mountains. Rocky Mountain Books. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-894765-69-5.

- "Tacomans Climb to Icy Crest of Mount Garibaldi". The Tacoma Daily Ledger. 1923-08-09. p. 2. Retrieved 2022-07-04 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Garibaldi Objective: Mountaineers Will Climb Difficult Canadian Peak". The Bellingham Herald. 1923-03-26. p. 3. Retrieved 2022-07-25 – via Newspapers.com.

- Eyton, Taryn (2021). "Garibaldi Lake and Taylor Meadows". Backpacking in Southwestern British Columbia: The Essential Guide to Overnight Hiking Trips. Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1-77164-669-7.

- "Bodies Of Mercy Plane Victims Found". McKinney Courier-Gazette. 1953-10-21. p. 8. Retrieved 2022-07-25 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Couple wed at 8,700 feet". Vancouver Sun. 1973-04-15. p. 1. Retrieved 2022-07-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Luxurious Ski Resort Lies Deserted". Vancouver Sun. 1970-01-08. p. 1. Retrieved 2022-07-26 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Developer proposes $50-million ski resort for Mount Garibaldi". Vancouver Sun. 1995-11-10. p. 56. Retrieved 2022-07-26 – via Newspapers.com.

- Anderson, Sean; Bryant, Leslie; Harris, Brian; Hoare, Jay; Hughes, Colin; Manyk, Mike; Mussio, Russell; Soroka, Stepan (2019). Vancouver, Coast & Mountains BC. Mussio Ventures. pp. 135, 183. ISBN 978-1-926806-95-2.

- "About Us". Black Tusk Snowmobile Club. Archived from the original on 2021-06-20. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- "Garibaldi Provincial Park: Diamond Head Area". BC Parks. Archived from the original on 2022-01-09. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- "Rescue Party Saves Skier". Edmonton Bulletin. 1950-04-12. p. 6. Retrieved 2022-07-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Rescuers Carry Injured Skier". Edmonton Journal. 1950-04-10. p. 14. Retrieved 2022-07-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dramatic 56-Hr. Rescue Gets Injured Skier to Hospital". Vancouver Sun. 1950-04-11. p. 1. Retrieved 2022-07-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Avalanche Kills Vancouver Youth". Vancouver Sun. 1961-07-20. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-07-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- "3 Trapped Mountaineers Sorry They Caused Search". Vancouver Sun. 1963-04-18. p. 37. Retrieved 2022-07-30 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

- "Garibaldi Volcano". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Natural Resources Canada. 2009-03-10. Archived from the original on 2009-06-07. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- "Mount Garibaldi". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved 2022-04-10.