Common Sense

Common Sense[1] is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political arguments to encourage common people in the Colonies to fight for egalitarian government. It was published anonymously on January 10, 1776,[2] at the beginning of the American Revolution and became an immediate sensation.

Pamphlet's original cover | |

| Author | Thomas Paine |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Published | January 10, 1776 |

| Pages | 47 |

| Text | Common Sense at Wikisource |

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | "Common Sense" |

| Type | City |

| Criteria |

|

| Designated | 1993 |

| Location | SE corner of S 3rd St. & Thomas Paine Place (Chancellor St), Philadelphia 39.9465505°N 75.1464207°W |

| Marker Text | At his print shop here, Robert Bell published the first edition of Thomas Paine's revolutionary pamphlet in January 1776. Arguing for a republican form of government under a written constitution, it played a key role in rallying American support for independence. |

It was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places. In proportion to the population of the colonies at that time (2.5 million), it had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history.[3] As of 2006, it remains the all-time best-selling American title and is still in print today.[4]

Common Sense made public a persuasive and impassioned case for independence, which had not yet been given serious intellectual consideration in either Britain or the American colonies. In England, John Cartwright had published Letters on American Independence in the pages of the Public Advertiser during the early spring of 1774 advocating legislative independence for the colonies while in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson had penned A Summary View of British America three months later. Neither, however, went as far as Paine in proposing full-fledged independence.[5] Paine connected independence with common dissenting Protestant beliefs as a means to present a distinctly American political identity and structured Common Sense as if it were a sermon.[6][7] Historian Gordon S. Wood described Common Sense as "the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era."[8]

The text was translated into French by Antoine Gilbert Griffet de Labaume in 1790.

Publication

Paine arrived in the American colonies in November 1774, shortly before the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Though the colonies and Great Britain had commenced hostilities against one another, the thought of independence was not initially entertained. Writing in 1778 of his early experiences in the colonies, Paine "found the disposition of the people such, that they might have been led by a thread and governed by a reed. Their attachment to Britain was obstinate, and it was, at that time, a kind of treason to speak against it. Their ideas of grievance operated without resentment, and their single object was reconciliation."[9] Paine quickly engrained himself in the Philadelphia newspaper business, and began writing Common Sense in late 1775 under the working title of Plain Truth. Though it began as a series of letters to be published in various Philadelphia papers, it grew too long and unwieldy to publish as letters, leading Paine to select the pamphlet form.[10]

Benjamin Rush recommended the publisher Robert Bell, promising Paine that although other printers might balk at the content of the pamphlet, Bell would not hesitate or delay its printing. The pamphlet was first published on January 10, 1776.[2] Bell zealously promoted the pamphlet in Philadelphia's papers, and demand grew so high as to require a second printing.[11] Paine, overjoyed with its success, endeavored to collect his share of the profits and donate them to purchase mittens for General Montgomery's troops, then encamped in frigid Quebec.[12] However, when Paine's chosen intermediaries audited Bell's accounts, they found that the pamphlet actually had made zero profits. Incensed, Paine ordered Bell not to proceed on a second edition, as he had planned several appendices to add to Common Sense. Bell ignored that and began advertising a "new edition".

While Bell believed that the advertisement would convince Paine to retain his services, it had the opposite effect. Paine secured the assistance of the Bradford brothers, publishers of The Pennsylvania Evening Post, and released his new edition, featuring several appendices and additional writings.[13] Bell began working on a second edition. This set off a month-long public debate between Bell and the still-anonymous Paine, conducted within the pages and advertisements of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, with each party charging the other with duplicity and fraud. Paine and Bell published several more editions through the end of their public squabble.

The publicity generated by the initial success and compounded by the publishing disagreements propelled the pamphlet to incredible sales and circulation. Following Paine's own estimate of the pamphlet's sales, some historians claim that Common Sense sold almost 100,000 copies in 1776,[14] and according to Paine, 120,000 copies were sold in the first three months. One biographer estimates that 500,000 copies were sold in the first year (in both America and Europe, predominantly France and Britain), and another writes that Paine's pamphlet went through 25 published editions in the first year alone.[8][15] However, some historians dispute these figures as implausible because of the literate population at the time and estimated the far upper limit as 75,000 copies.[16][17]

Aside from the printed pamphlet itself, there were many handwritten summaries and whole copies circulated. Paine also granted publishing rights to nearly every imprint which requested them, including several international editions.[18] It was immensely popular in France, where it was published without its diatribes against monarchy.[19] At least one newspaper printed the entire pamphlet: the Connecticut Courant in its issue of February 19, 1776.[20] Writing in 1956, Richard Gimbel estimated, in terms of circulation and impact, that an "equivalent sale today, based on the present population of the United States, would be more than six-and-one-half million copies within the short space of three months".[18]

For nearly three months, Paine managed to maintain his anonymity, even during Bell's potent newspaper polemics. His name did not become officially connected with the independence controversy until March 30, 1776.[21] Paine never recouped the profits that he felt were due to him from Bell's first edition. Ultimately, he lost money on the Bradford printing as well, and because he decided to repudiate his copyright, he never profited from Common Sense.

Sections

The first and subsequent editions divided the pamphlet into four sections.

I. Of the Origin and Design of Government in General, With Concise Remarks on the English Constitution

In his first section, Paine related common Enlightenment theories of the state of nature to establish a foundation for republican government. Paine began the section by making a distinction between society and government and argues that government is a "necessary evil." He illustrates the power of society to create and maintain happiness in man through the example of a few isolated people who find it easier to live together rather than apart, thus creating society. As society continues to grow, a government becomes necessary to prevent the natural evil Paine saw in man.

To promote civil society through laws and account for the impossibility of all people meeting centrally to make laws, representation and elections become necessary. As that model was clearly intended to mirror the situation of the colonists at the time of publication, Paine went on to consider the English constitution.

Paine found two tyrannies in the English constitution: monarchical and aristocratic tyranny in the king and peers, who rule by heredity and contribute nothing to the people. Paine criticized the English constitution by examining the relationship between the king, the peers, and the commons.

II. Of Monarchy and Hereditary Succession

The second section considers monarchy first from a biblical perspective and then from a historical perspective. He begins by arguing that since all men are equal at creation, the distinction between kings and subjects is a false one. Paine then quotes a sequence of biblical passages to refute the divine right of Kings. After citing Matthew 22:21, he highlights Gideon’s refusal to heed the people's call to rule, citing Judges 8:22. He then reproduces the majority of 1 Samuel 8 (wherein Samuel relays God's objections to the people's demand for a king) and concludes: “the Almighty hath here entered his protest against monarchical government...”

Paine then examines some of the problems that kings and monarchies have caused in the past and concludes:

In England a king hath little more to do than to make war and give away places; which in plain terms, is to impoverish the nation and set it together by the ears. A pretty business indeed for a man to be allowed eight hundred thousand sterling a year for, and worshipped into the bargain! Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.

— Thomas Paine[22]

Paine also attacks one type of "mixed state," the constitutional monarchy promoted by John Locke, in which the powers of government are separated between a Parliament or Congress, which makes the laws, and a monarch, who executes them. The constitutional monarchy, according to Locke, would limit the powers of the king sufficiently to ensure that the realm would remain lawful rather than easily becoming tyrannical. According to Paine, however, such limits are insufficient. In the mixed state, power tends to concentrate into the hands of the monarch, eventually permitting him to transcend any limitations placed upon him. Paine questions why the supporters of the mixed state, since they concede that the power of the monarch is dangerous, wish to include a monarch in their scheme of government in the first place.

III. Thoughts on the Present State of American Affairs

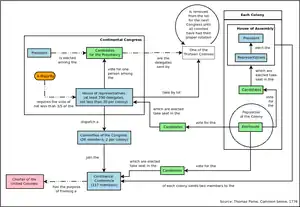

In the third section, Paine examines the hostilities between Britain and the American colonies and argues that the best course of action is independence. Paine proposes a Continental Charter (or Charter of the United Colonies) that would be an American Magna Carta. Paine writes that a Continental Charter "should come from some intermediate body between the Congress and the people" and outlines a Continental Conference that could draft a Continental Charter.[23] Each colony would hold elections for five representatives at large, who would be accompanied by two members of the house of assembly of each colony and two members of Congress from each colony, for a total of nine representatives from each colony in the Continental Conference. The Conference would then meet and draft a Continental Charter that would secure "freedom and property to all men, and… the free exercise of religion".[23] The Continental Charter would also outline a new national government, which Paine thought would take the form of a Congress.

During the American Revolutionary War, the British implemented several policies which allowed fugitive slaves fleeing from American enslavers to find refuge within British lines. Writing in response to these policies, Paine wrote in the third section that Britain "hath stirred up the Indians and the Negroes to destroy us".[24]

Paine suggested that a congress may be created in the following way: each colony should be divided in districts, and each district would "send a proper number of delegates to Congress."[23] Paine thought that each colony should send at least 30 delegates to Congress and that the total number of delegates in Congress should be at least 390. The Congress would meet annually and elect a president. Each colony would be put into a lottery; the president would be elected, by the whole congress, from the delegation of the colony that was selected in the lottery. After a colony was selected, it would be removed from subsequent lotteries until all of the colonies had been selected, at which point the lottery would start anew. Electing a president or passing a law would require three-fifths of the congress.

IV. On the Present Ability of America, With Some Miscellaneous Reflections

The fourth section of the pamphlet includes Paine's optimistic view of America's military potential at the time of the revolution. For example, he spends pages describing how colonial shipyards, by using the large amounts of lumber available in the country, could quickly create a navy that could rival the Royal Navy.

Impact and response

Heavy advertisement by both Bell and Paine and the immense publicity created by their publishing quarrel made Common Sense an immediate sensation not only in Philadelphia but also across the Thirteen Colonies. Early "reviewers" (mainly letter excerpts published anonymously in colonial newspapers) touted the clear and rational case for independence put forth by Paine. One Marylander wrote to the Pennsylvania Evening Post on February 6, 1776, that "if you know the author of COMMON SENSE, tell him he has done wonders and worked miracles. His stile [sic] is plain and nervous; his facts are true; his reasoning, just and conclusive". [25] The author went on to claim that the pamphlet was highly persuasive in swaying people towards independence. The mass appeal, one later reviewer noted, was caused by Paine's dramatic calls for popular support of revolution, "giv[ing] liberty to every individual to contribute materials for that great building, the grand charter of American Liberty".[26] Paine's vision of a radical democracy, unlike the checked and balanced nation later favored by conservatives like John Adams, was highly attractive to the popular audience which read and reread Common Sense. In the months leading up to the Declaration of Independence, many more reviewers noted that the two main themes (direct and passionate style and calls for individual empowerment) were decisive in swaying the Colonists from reconciliation to rebellion. The pamphlet was also highly successful because of a brilliant marketing tactic planned by Paine. He and Bell timed the first edition to be published at around the same time as a proclamation on the colonies by King George III, hoping to contrast the strong, monarchical message with the heavily anti-monarchical Common Sense.[11] Luckily for Paine, the speech and the first advertisement of the pamphlet appeared on the same day within the pages of The Pennsylvania Evening Post.[27]

While Paine focused his style and address towards the common people, the arguments he made touched on prescient debates of morals, government, and the mechanisms of democracy.[28] That gave Common Sense a "second life" in the very public call-and-response nature of newspaper debates made by intellectual men of letters throughout Philadelphia. Paine's formulation of "war for an idea" led to, as Eric Foner describes it, "a torrent of letters, pamphlets, and broadsides on independence and the meaning of republican government... attacking or defending, or extending and refining Paine's ideas".[29][30]

John Adams, who would succeed George Washington to become the new nation's second president, in his Thoughts on Government wrote that Paine's ideal sketched in Common Sense was "so democratical, without any restraint or even an attempt at any equilibrium or counter poise, that it must produce confusion and every evil work."[31] Others, such as the writer calling himself "Cato," denounced Paine as dangerous and his ideas as violent.[32] Paine was also an active and willing participant in what would become essentially a six-month publicity tour for independence. Writing as "The Forester," he responded to Cato and other critics in the pages of Philadelphian papers with passion and declared again in sweeping language that their conflict was not only with Great Britain but also with the tyranny inevitably resulting from monarchical rule.[33]

Later scholars have assessed the influence of Common Sense in several ways. Some, like A. Owen Aldridge, emphasize that Common Sense could hardly be said to embody a particular ideology, and that "even Paine himself may not have been cognizant of the ultimate source of many of his concepts." They make the point that much of the pamphlet's value came as a result of the context in which it was published.[34] Eric Foner wrote that the pamphlet touched a radical populace at the height of their radicalism, which culminated in Pennsylvania with a new constitution aligned along Paine's principles.[35] Many have noted that Paine's skills were chiefly in persuasion and propaganda and that no matter the content of his ideas, the fervor of his conviction and the various tools he employed on his readers (such as asserting his Christianity when he really was a Deist), Common Sense was bound for success.[36] Still others emphasized the uniqueness of Paine's vision, with Craig Nelson calling him a "pragmatic utopian" who de-emphasized economic arguments in favor of moralistic ones, thus giving credence to the argument that Common Sense was propaganda.[37]

In response to Common Sense, Rev. Charles Inglis, then the Anglican cleric of Trinity Church in New York, responded to Paine on behalf of colonists loyal to the Crown with a treatise entitled The True Interest of America Impartially Stated.[38]

See also

- The American Crisis,

- Rights of Man, and

- The Age of Reason, also written by Thomas Paine

- Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania

- American philosophy

Citations

- Full title: Common Sense; Addressed to the Inhabitants of America, on the Following Interesting Subjects.

- Foner, Philip. "Thomas Paine". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- Conway (1893)

- Kaye (2005), p. 43.

- Chiu, Frances. A Routledge Guidebook to Paine's Rights of Man. Routledge, 2020. Pp. 46-56.

- Wood (2002), pp. 55–56

- Anthony J. Di Lorenzo, "Dissenting Protestantism as a Language of Revolution in Thomas Paine's Common Sense" (registration required) in Eighteenth-Century Thought, Vol. 4, 2009. ISSN 1545-0449.

- Wood (2002), p. 55

- Gimbel (1956), p. 15

- Gimbel (1956), p. 17

- Gimbel (1956), p. 21

- Gimbel (1956), p. 22

- Gimbel (1956), p. 23

- Foot & Kramnick (1987), p. 10

- Isaac Kramnick, "Introduction", in Thomas Paine, Common Sense (New York: Penguin, 1986), p. 8

- Trish Loughran, The Republic in Print: Print Culture in the Age of U.S. Nation Building, 1770–1870 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007)

- Raphael, Ray (20 March 2013). "Thomas Paine's Inflated Numbers". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Gimbel (1956), p. 57

- Foot & Kramnick (1987), pp. 10–11

- Aldridge (1984), p. 45

- Aldridge (1984), p. 43

- Paine, Common Sense, excerpted from The Thomas Paine Reader, p. 79

- Paine, Common Sense, pp. 96–97.

- Paine, Thomas (21 March 2018). Common Sense & the Rights of Man: Words of a Visionary That Sparked the Revolution and Remained the Core of American Democratic Principles. ISBN 9788027241521.

- "Philadelphia, February 13", Pennsylvania Evening Post (Philadelphia) February 13, 1776, p. 77.

- "To the Author of Common Sense, Number IV," New York Journal (New York) March 7, 1776, p. 1.

- Gimbel (1956), pp. 21–22

- Aldridge (1984), p. 18

- Conway (1893), pp. 66–67

- Foner (2004), p. 119

- Foot & Kramnick (1987), p. 11

- Foner (2004), p. 120

- Conway (1893), pp. 72–73

- Aldridge (1984), p. 19

- Foner (2004), p. 132

- Jerome D. Wilson and William F. Ricketson, Thomas Paine – Updated Edition (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1989), pp. 26–27

- Craig Nelson, Thomas Paine (New York: Viking, 2006), pp. 81–83

- Inglis, Charles. Charles Inglis The True Interest of America Impartially Stated, In Certain Strictures, On a Pamphlet Entitled Common Sense. Philadelphia, 1776

General and cited references

Secondary sources

- Aldridge, A. Owen (1984), Thomas Paine's American Ideology, University of Delaware Press, ISBN 0-874-13260-6

- Chiu, Frances A. (2020), The Routledge Guidebook to Paine's Rights of Man

- Conway, Moncure Daniel (1893), The Life of Thomas Paine (See Ch. VI.)

- Ferguson, Robert A. (2000), "The Commonalities of Common Sense", William and Mary Quarterly, 57 (3): 465–504, doi:10.2307/2674263, JSTOR 2674263

- Foner, Eric (2004), Tom Paine and Revolutionary America

- Gimbel, Richard (1956), A Bibliographical Check List of Common Sense, With an Account of Its Publication, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, Thomas Paine, "The [American] Crisis No. VII", Pennsylvania Packet

- Jordan, Winthrop D. (1973), "Familial Politics: Thomas Paine and the Killing of the King, 1776", Journal of American History, 60 (2): 294–308, doi:10.2307/2936777, JSTOR 2936777

- Kaye, Harvey J. (2005), Thomas Paine and the Promise of America, New York: Hill and Wang, ISBN 0-8090-9344-8

- Nelson, Craig (2007), Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations, New York: Penguin Books

- Wood, Gordon S. (2002), The American Revolution: A History, New York: Modern Library, ISBN 0-679-64057-6

Primary sources

- Paine, Thomas (1986) [1776], Kramnick, Isaac (ed.), Common Sense, New York: Penguin Classics, ISBN 0-14-039016-2

- Foot, Michael; Kramnick, Isaac, eds. (1987), The Thomas Paine Reader, Penguin Classics, ISBN 0-14-044496-3

External links

- "Common Sense: The Rhetoric of Popular Democracy"—lesson plan for grades 9–12 from the National Endowment for the Humanities

- Online full text scan and downloadable PDF at Google Books

- Common Sense by Thomas Paine—at ushistory.org

- Project Gutenberg: #147 and #3755

Common Sense public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Common Sense public domain audiobook at LibriVox