Constellation family

Constellation families are collections of constellations sharing some defining characteristic, such as proximity on the celestial sphere, common historical origin, or common mythological theme. In the Western tradition, most of the northern constellations stem from Ptolemy's list in the Almagest (which in turn has roots that go back to Mesopotamian astronomy), and most of the far southern constellations were introduced by sailors and astronomers who traveled to the south in the 16th to 18th centuries. Separate traditions arose in India and China.

Menzel's families

Entirely northern:

|

Primarily northern:

|

Straddling ecliptic:

|

Split between north and south:

|

Entirely southern:

|

Primarily southern:

|

Donald H. Menzel, director of the Harvard Observatory, gathered several traditional groups in his popular account, A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (1975),[1] and adjusted and regularized them so that his handful of groups covered all 88 of the modern constellations.

Of these families, one (Zodiac) straddles the ecliptic which divides the sky into north and south; one (Hercules) has nearly equal portions in the north and south; two are primarily in one hemisphere (Heavenly Waters in the south and Perseus in the north); and four are entirely in one hemisphere (La Caille, Bayer, and Orion in the south and Ursa Major in the north).

Ursa Major Family

The Ursa Major Family includes 10 northern constellations in the vicinity of Ursa Major: Ursa Major itself, Ursa Minor, Draco, Canes Venatici, Boötes, Coma Berenices, Corona Borealis, Camelopardalis, Lynx, and Leo Minor. The eponymous constellation Ursa Major contains the famous Big Dipper.

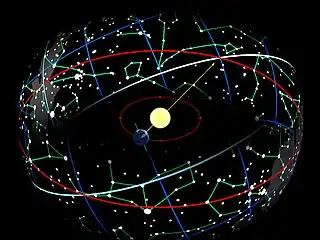

Zodiac

The Zodiac is a group of 12 constellations: Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpius, Sagittarius, Capricornus, Aquarius, Pisces. Some version of these constellations are found in traditions around the world, for this band around the celestial sphere includes the ecliptic, the apparent path of the sun through the year. These constellations therefore are all associated with zodiac signs. (The ecliptic also passes through the constellation Ophiuchus, which does not have an associated zodiac sign.)

Perseus Family

The Perseus Family includes several constellations associated with the Perseus myth: Cassiopeia, Cepheus, Andromeda, Perseus, Pegasus, and Cetus (representing the monster sent to devour Andromeda). Menzel also included a few neighboring constellations: Auriga, Lacerta, and Triangulum. Except for Cetus, these constellations all lie north of the ecliptic. The group reaches from near the north celestial pole to declination −30°.

Hercules Family

The Hercules Family is a group of constellations connected mainly by their adjacency on the celestial sphere. It is Menzel's largest grouping, and extends from declination +60° to −70°, mostly in the western hemisphere. It includes Hercules, Sagitta, Aquila, Lyra, Cygnus, Vulpecula, Hydra, Sextans, Crater, Corvus, Ophiuchus, Serpens, Scutum, Centaurus, Lupus, Corona Australis, Ara, Triangulum Australe, and Crux.

Orion Family

The Orion Family, on the opposite side of the sky from the Hercules Family, includes Orion, Canis Major, Canis Minor, Lepus, and Monoceros. This group of constellations draws from Greek myth, representing the hunter (Orion) and his two dogs (Canis Major and Canis Minor) chasing the hare (Lepus). Menzel added the unicorn (Monoceros) for completeness.

Heavenly Waters

The Heavenly Waters draws from the Mesopotamian tradition associating the dim area between Sagittarius and Orion with the god Ea and the Waters of the Abyss.[2] Aquarius and Capricornus, derived from Mesopotamian constellations, would have been natural members had they not already been assigned to the Zodiac group. Instead, Menzel expanded the area and included several disparate constellations, most associated with water in some form: Delphinus, Equuleus, Eridanus, Piscis Austrinus, Carina, Puppis, Vela, Pyxis, and Columba. Carina, Puppis, and Vela historically formed part of the former constellation Argo Navis, which in Greek tradition represented the ship of Jason.

Bayer Family

The Bayer Family collects several southern constellations first introduced by Petrus Plancius on several celestial globes in the late 16th century, based on astronomical observations by the Dutch explorers Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. The constellations were named mostly for exotic animals reported in the travel journals of that period, and were copied in Johann Bayer's influential celestial atlas Uranometria in 1603. The group includes Hydrus, Dorado, Volans, Apus, Pavo, Grus, Phoenix, Tucana, Indus, Chamaeleon, and Musca. Bayer labeled Musca as "Apis" (the Bee), but over time it was renamed. (Bayer's twelfth new southern constellation, Triangulum Australe, was placed by Menzel in the Hercules Family.) The Bayer Family circles the south celestial pole, forming an irregular contiguous band. Because these constellations are located in the far southern sky, their stars were not visible to the ancient Greeks and Romans.

La Caille Family

The La Caille Family comprises 12 of the 13 constellations introduced by Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille in 1756 to represent scientific instruments, together with Mensa, which commemorates Table Mountain ("Mons Mensa") in South Africa, where he set up his telescope. The group includes Norma, Circinus, Telescopium, Microscopium, Sculptor, Fornax, Caelum, Horologium, Octans, Mensa, Reticulum, Pictor, and Antlia. These dim constellations are scattered throughout the far southern sky, and their stars were mostly not visible to the ancient Greeks and Romans. (Menzel assigned Pyxis, the remaining Lacaille instrument, to the Heavenly Waters group.)

References

- Donald H. Menzel (1975). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets. HarperCollins. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108: 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

Other sources

- Majumdar, R. C., et al. (1951), The Vedic Age (vol. 1), The History and Culture of the Indian People (11 vols.), Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan (publisher), 1951, Delhi, India.

- Sundaramoorthy, G. (1974), "The Contribution of the Cult of Sacrifice to the Development of Indian Astronomy", Indian Journal of the History of Science, Indian National Science Academy, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 100–106, 1974, Bombay, India.

- Das, S. R. (1930), "Some Notes on Indian Astronomy", Isis (journal), University of Chicago, Vol. 14, No. 2, October, 1930, pp. 388–402.

- Neugebauer, Otto, & Parker, Richard A. (1960), Egyptian Astronomical Texts (4 vols.), Lund Humphries (publisher), London.

- Clagett, Marshall (1989), Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy (vol. 2), Ancient Egyptian Science – A Source Book (3 vols.), [Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society], American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 1989.

- Condos, Theony (1997), Star Myths of the Greeks and Romans: A Sourcebook, Phanes Press, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1997.

- Young, Charles Augustus (1888), A Text-Book of General Astronomy for Colleges and Scientific Schools, Ginn & Company (publisher), Boston, 1888.

- Schaaf, Fred (2007), The 50 Best Sights in Astronomy and How to See Them – Observing Eclipses, Bright Comets, Meteor Showers, and Other Celestial Wonders, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2007.

- Olcott, William Tyler (1911), Star Lore of All Ages, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1911