Craniopharyngioma

A craniopharyngioma is a rare type of brain tumor derived from pituitary gland embryonic tissue[1] that occurs most commonly in children, but also affects adults. It may present at any age, even in the prenatal and neonatal periods, but peak incidence rates are childhood-onset at 5–14 years and adult-onset at 50–74 years.[2] People may present with bitemporal inferior quadrantanopia leading to bitemporal hemianopsia, as the tumor may compress the optic chiasm. It has a point prevalence around two per 1,000,000.[3] Craniopharyngiomas are distinct from Rathke's cleft tumours and intrasellar arachnoid cysts.[4]

| Pituicytoma | |

|---|---|

| |

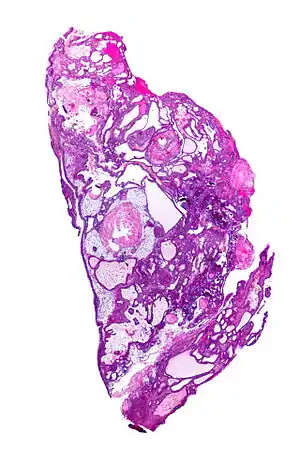

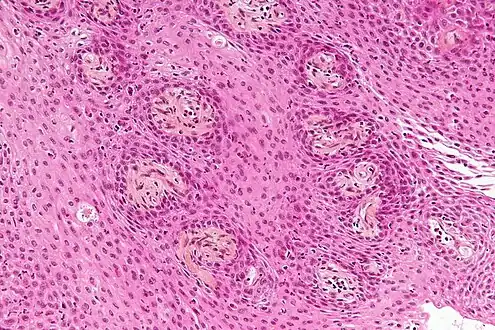

| Very low magnification micrograph of an adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. HPS stain. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Symptoms and signs

Craniopharyngiomas are almost always benign.[5] However, as with many brain tumors, their treatment can be difficult, and significant morbidities are associated with both the tumor and treatment.

- Headache (obstructive hydrocephalus)[6]

- Hypersomnia[7]

- Myxedema

- Postsurgical weight gain[8]

- Polydipsia[9]

- Polyuria (diabetes insipidus) [10]

- Vision loss (bitemporal hemianopia)[11]

- Vomiting[12]

- Often occurs after treatment

- Growth hormone (GH) insufficiency, caused by the reduction in GH production - symptoms include:

- Stunted growth and delayed puberty (in children)

- General fatigue, loss of muscle mass and tone (in adults)

- Pituitary insufficiency

- Often occurs to some degree because craniopharyngiomas develop in the area of the pituitary stalk, which can affect the function of the pituitary gland and many other hormones[13]

- Reduction in prolactin production is very uncommon and occurs with severe pituitary insufficiency.

- Large pituitary tumors can paradoxically elevate blood prolactin levels due to the "stalk effect". This elevation occurs as a result of the compression of the pituitary stalk, which interferes with the brain's control of prolactin production.

- In premenopausal women, elevated prolactin can lead to reduction or loss of menstrual periods and/or breast milk production (galactorrhea).

- With stalk effect, prolactin levels are usually only slightly elevated, as opposed to prolactinomas in which the prolactin level is usually very high.

- Diabetes insipidus[14] occurs due to the absence of a posterior pituitary hormone called antidiuretic hormone. Symptoms include:

- Excessive thirst

- Excessive urination

- Adrenal insufficiency[13] occurs because of a reduction in ACTH production, a reduction in cortisol. In severe cases, it can be fatal. Symptoms include:

Mechanisms

Craniopharyngioma is a rare, usually suprasellar[15] neoplasm, which may be cystic, that develops from nests of epithelium derived from Rathke's pouch.[16][17] Rathke's pouch is an embryonic precursor of the anterior pituitary.

Craniopharyngiomas are typically very slow-growing tumors. They arise from the cells along the pituitary stalk, specifically from nests of odontogenic (tooth-forming) epithelium within the suprasellar/diencephalic region, so contain deposits of calcium that are evident on an X-ray.[18]

Diagnosis

Imaging scans for craniopharyngioma

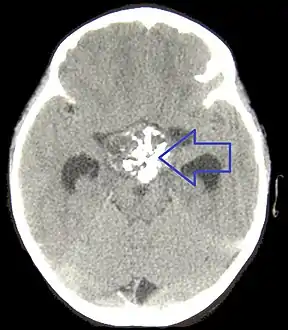

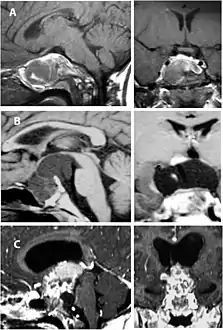

A physician can conduct a few scans and tests to diagnose a person with craniopharyngioma.[19] High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is commonly used as a diagnostic tool; however, computer tomography (CT) remains the gold standard imaging choice for craniopharyngioma diagnosis as it can detect the severity of the calcification within the tumour.[20]

In some cases, a powerful 3T (Tesla) MRI scanner can help define the location of critical brain structures affected by the tumor. The histologic pattern consists of nesting of squamous epithelium bordered by radially arranged cells. It is frequently accompanied by calcium deposition and may have a microscopic papillary architecture. A computed tomography (CT) scan is also a good diagnostic tool, as it detects calcification in the tumor.[21]

Two distinct types are recognized:[22][23]

- Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas, which resemble ameloblastomas (the most common type of odontogenic tumor), are characterized by activating CTNNB1 mutations.

- Papillary craniopharyngiomas are characterized by BRAFv600E mutations.[24]

In the adamantinomatous type, calcifications are visible on neuroimaging and are helpful in diagnosis.

The papillary type rarely calcifies. A vast majority of craniopharyngiomas in children are adamantinomatous, whereas both subtypes are common in adults. Mixed-type tumors also occur.[25]

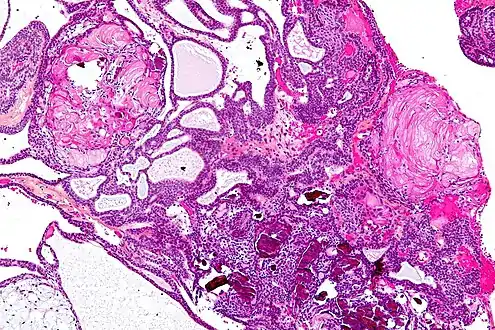

On macroscopic examination, craniopharyngiomas are cystic or partially cystic with solid areas. On light microscopy, the cysts are seen to be lined by stratified squamous epithelium. Keratin pearls may also be seen. The cysts are usually filled with a yellow, viscous fluid rich in cholesterol crystals. Of a long list of possible symptoms, the most common presentations include headaches, growth failure, and bitemporal hemianopsia.

CT scan showing a craniopharyngioma

CT scan showing a craniopharyngioma Enhanced T1 weighted MRIs of craniopharyngiomas

Enhanced T1 weighted MRIs of craniopharyngiomas Micrograph showing the characteristic features of an adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma - cystic spaces, calcifications, and "wet" keratin, HPS stain

Micrograph showing the characteristic features of an adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma - cystic spaces, calcifications, and "wet" keratin, HPS stain Micrograph showing a papillary craniopharyngioma, HPS stain

Micrograph showing a papillary craniopharyngioma, HPS stain

Malignant craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngiomas are usually successfully managed with a combination of adjuvant chemotherapy and neurosurgery. Recent research describes the rare occurrence of malignant transformations of these normally benign tumors. Malignant craniopharyngiomas can occur at any age, are slightly more common in females, and are usually of the adamantinomatous type.[26]

The malignant transformations can take years to occur (although one in five of the diagnosed cases were de novo transformations), hence the need for lengthier follow-up in patients diagnosed with the more common benign forms.[26]

No link has been found between malignancy and initial chemoradiotherapy treatment,[26] and the overall survival rate was very poor with median survival being 6 months after diagnosis of malignancy.

Prevention

Although the causes of craniopharyngioma are unknown, it can occur in both children and adults, with a peak in incidence at 9 to 14 years of age. About 120 cases are diagnosed each year in the United States in patients under the age of 19. More than 50% of all patients with craniopharyngioma are under the age of 18 years. No clear association of the tumor exists with a particular gender or race. Craniopharyngiomas do not appear to "run in families" or to be directly inherited from the parents.

Treatment

Treatment generally consists of subfrontal or transsphenoidal excision. Endoscopic surgery through the nose[27][28] often performed by a team of neurosurgeons and ENT, is an alternative to transcranial surgery done by making an opening in the skull. Because of the location of the craniopharyngioma in the skull base of the brain, a surgical navigation system might be used to verify the position of surgical tools during the operation.[29]

Additional radiotherapy is used if total removal is not possible. Due to the poor outcomes associated with damage to the pituitary and hypothalamus from surgical removal and radiation, experimental therapies using intracavitary phosphorus-32, yttrium, or bleomycin delivered via an external reservoir are sometimes employed, especially in young patients. The tumor, being in the pituitary gland, can cause secondary health problems. The immune system, thyroid levels, growth hormone levels, and testosterone levels can be compromised from craniopharyngioma. All of these health problems can be treated with modern medicine.[30] No high quality evidence has evaluated the use of bleomycin in this condition.[31]

Proton therapy affords a reduction in dose to critical structures compared to conventional photon radiation, including IMRT, for patients with craniopharyngioma.[32]

The most effective treatment 'package' for the malignant craniopharyngiomas described in literature is a combination 'gross total resective' surgery with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. The chemotherapy drugs paclitaxel and carboplatin have shown a clinical (but not statistical) significance in increasing the survival rate in patients who have had gross total resections of their malignant tumours.[26]

Prognosis

Craniopharyngiomas are generally benign but are known to recur after resection. Recent research[26] has demonstrated a malignant (but rare) tendency of craniopharyngiomas. These malignant craniopharyngiomas are very rare but are associated with poor prognosis.

Recent research

Current research has shown ways of treating the tumors in a less invasive way while others have shown how the hypothalamus can be stimulated along with the tumor to prevent the child and adult with the tumor to become obese. A childhood craniopharyngioma is commonly cystic in nature.[33] Limited surgery minimizing hypothalamic damage may decrease the severe obesity rate at the expense of the need for radiotherapy to complete the treatment.[34]

Role of radiotherapy:

Aggressive attempts at total removal do result in prolonged progression-free survival in most patients, but for tumors that clearly involve the hypothalamus, complications associated with radical surgery have prompted to adopt a combined strategy of conservative surgery and radiation therapy to residual tumor with as high a rate of cure. This strategy seems to offer the best long-term control rates with acceptable morbidity. But optimal management of craniopharyngiomas remains controversial. Although it is generally recommended that radiotherapy is given following subtotal excision of a craniopharyngioma, it remains unclear as to whether all patients with residual tumour should receive immediate or differed at relapse radiotherapy.[35] Surgery and radiotherapy are the cornerstones in therapeutic management of craniopharyngioma. Radical excision is associated with a risk of mortality or morbidity particularly as hypothalamic damage, visual deterioration, and endocrine complication between 45 and 90% of cases. The close proximity to neighboring eloquent structures poses a particular challenge to radiation therapy. Modern treatment technologies including fractionated 3-D conformal radiotherapy,[36] intensity modulated radiation therapy, and recently proton therapy are able to precisely cover the target while preserving surrounding tissue, Tumor controls in excess of 90% can be achieved. Alternative treatments consisting of radiosurgery, intracavitary application of isotopes, and brachytherapy also offer an acceptable tumor control and might be given in selected cases. More research is needed to establish the role of each treatment modality.[37]

References

- "Craniopharyngioma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Müller HL (June 2014). "Craniopharyngioma". Endocrine Reviews. 35 (3): 513–43. doi:10.1210/er.2013-1115. PMID 24467716.

- Garnett MR, Puget S, Grill J, Sainte-Rose C (April 2007). "Craniopharyngioma". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2: 18. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-18. PMC 1855047. PMID 17425791.

- Shin JL, Asa SL, Woodhouse LJ, Smyth HS, Ezzat S (November 1999). "Cystic lesions of the pituitary: clinicopathological features distinguishing craniopharyngioma, Rathke's cleft cyst, and arachnoid cyst". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 84 (11): 3972–82. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.11.6114. PMID 10566636.

- Garrè ML, Cama A (August 2007). "Craniopharyngioma: modern concepts in pathogenesis and treatment". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 19 (4): 471–479. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282495a22. PMID 17630614. S2CID 25955091.

- "Hydrocephalus Fact Sheet". NINDS. April 5, 2016. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- Reynolds CF, O'Hara R (October 2013). "DSM-5 sleep-wake disorders classification: overview for use in clinical practice". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (10): 1099–1101. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13010058. PMID 24084814.

The aim is simply to acknowledge the bidirectional and interactive effects between sleep disorders and coexisting medical and psychiatric illnesses.

- Ahmet A, Blaser S, Stephens D, Guger S, Rutkas JT, Hamilton J (February 2006). "Weight gain in craniopharyngioma--a model for hypothalamic obesity". Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 19 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1515/jpem.2006.19.2.121. PMID 16562584. S2CID 35451441.

- Porth CM (1990). Pathophysiology: Concepts of altered health states. Philadelphia: Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company.

- "Diabetes Insipidus". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- "Bitemporal hemianopsia". Science Daily.

- "Pediatric Vomiting". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- "Craniopharyngioma | UCLA Pituitary Tumor Program". pituitary.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- "Diabetes insipidus - Symptoms and causes - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- Rodriguez FJ, Scheithauer BW, Tsunoda S, Kovacs K, Vidal S, Piepgras DG (July 2007). "The spectrum of malignancy in craniopharyngioma". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 31 (7): 1020–1028. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e31802d8a96. PMID 17592268. S2CID 36172034.

- Moore KD, Couldwell WT, et al. (Joint Tumor Section of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons & the Congress of Neurological Surgeons) (January 15, 2000). "41. Craniopharyngioma". In Bernstein M, Berger MS (eds.). Neuro-oncology: the essentials. Thieme. pp. 409–418. ISBN 978-0-86577-880-1. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- "Craniopharyngioma". Organ System Pathology Images, The Internet Pathology Laboratory for Medical Education. The University of Utah Eccles Health Sciences Library. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- "Craniopharyngioma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- "Craniopharyngioma - Childhood: Diagnosis | Cancer.Net". Cancer.Net. 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- Müller, Hermann L. (2020). "The Diagnosis and Treatment of Craniopharyngioma". Neuroendocrinology. 110 (9–10): 753–766. doi:10.1159/000504512. ISSN 0028-3835. PMID 31678973. S2CID 207904477.

- "Craniopharyngioma". UCLA Health.

- Sekine S, Shibata T, Kokubu A, Morishita Y, Noguchi M, Nakanishi Y, et al. (December 2002). "Craniopharyngiomas of adamantinomatous type harbor beta-catenin gene mutations". The American Journal of Pathology. 161 (6): 1997–2001. doi:10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64477-x. PMC 1850925. PMID 12466115.

- Sekine S, Takata T, Shibata T, Mori M, Morishita Y, Noguchi M, et al. (December 2004). "Expression of enamel proteins and LEF1 in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma: evidence for its odontogenic epithelial differentiation". Histopathology. 45 (6): 573–579. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.02029.x. PMID 15569047. S2CID 35192721.

- Brastianos PK, Taylor-Weiner A, Manley PE, Jones RT, Dias-Santagata D, Thorner AR, et al. (February 2014). "Exome sequencing identifies BRAF mutations in papillary craniopharyngiomas". Nature Genetics. 46 (2): 161–165. doi:10.1038/ng.2868. PMC 3982316. PMID 24413733.

- Weiner HL, Wisoff JH, Rosenberg ME, Kupersmith MJ, Cohen H, Zagzag D, et al. (December 1994). "Craniopharyngiomas: a clinicopathological analysis of factors predictive of recurrence and functional outcome". Neurosurgery. 35 (6): 1001–10, discussion 1010–1. doi:10.1227/00006123-199412000-00001. PMID 7885544.

- Sofela AA, Hettige S, Curran O, Bassi S (September 2014). "Malignant transformation in craniopharyngiomas". Neurosurgery. 75 (3): 306–14, discussion 314. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000000380. PMID 24978859. S2CID 44735428.

- Dhandapani S, Singh H, Negm HM, Cohen S, Souweidane MM, Greenfield JP, et al. (February 2017). "Endonasal endoscopic reoperation for residual or recurrent craniopharyngiomas". Journal of Neurosurgery. 126 (2): 418–430. doi:10.3171/2016.1.JNS152238. PMID 27153172.

- "Endoscopic pituitary surgery (transsphenoidal)". Mayfield Brain & Spine. Mayfield Clinic.

- "Use of Surgical Navigation for Craniopharyngioma Removal". January 2013.

- Wisoff JH (February 2008). "Craniopharyngioma". Journal of Neurosurgery. Pediatrics. 1 (2): 124–5, discussion 125. doi:10.3171/PED/2008/1/2/124. PMID 18352780.

- Zhang S, Fang Y, Cai BW, Xu JG, You C (July 2016). "Intracystic bleomycin for cystic craniopharyngiomas in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (7): CD008890. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008890.pub4. PMC 6457977. PMID 27416004.

- "Treating Pediatric Tumors With Proton Therapy Current Practice, Opportunities and Challenges". IBA. October 2015. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

- Roth C, Wilken B, Hanefeld F, Schröter W, Leonhardt U (January 1998). "Hyperphagia in children with craniopharyngioma is associated with hyperleptinaemia and a failure in the downregulation of appetite". European Journal of Endocrinology. 138 (1): 89–91. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1380089. PMID 9461323.

- Elowe-Gruau E, Beltrand J, Brauner R, Pinto G, Samara-Boustani D, Thalassinos C, et al. (June 2013). "Childhood craniopharyngioma: hypothalamus-sparing surgery decreases the risk of obesity". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 98 (6): 2376–2382. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3928. PMID 23633208.

- Chargari C, Bauduceau O, Bauduceau B, Camparo P, Ceccaldi B, Fayolle M, et al. (November 2007). "[Craniopharyngiomas: role of radiotherapy]". Bulletin du Cancer. 94 (11): 987–994. PMID 18055317.

- "Three Dimensional (3D) Conformal Radiation Therapy". hillman.upmc.com. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- Kortmann RD (2011-12-20). "Different approaches in radiation therapy of craniopharyngioma". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2: 100. doi:10.3389/fendo.2011.00100. PMC 3356005. PMID 22654836.