Cretan Revolt (1897–1898)

The Cretan Revolt of 1897–1898 was a successful insurrection by the Greek population of Crete against the rule of the Ottoman Empire after decades of rising tensions. The Greek insurrectionists received supplies and armed support first from the Kingdom of Greece; then later from the Great Powers: the United Kingdom,[3] France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Germany and Russia. The conflict ended in 1898 with Cretan-allied victory and Ottoman retreat when the Great Powers cut their funding and proposed a resolution which stipulated:

- The Island of Crete become an autonomous state under the nominal sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire, with the Prince George of Greece as governor. [1][3]

- The Ottoman Empire recognize the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Greece. [1][3]

- The Kingdom of Greece recognize the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire. [3]

| Cretan Revolt of 1897-1898 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Turkish War (1897) and the Cretan revolts | |||||||

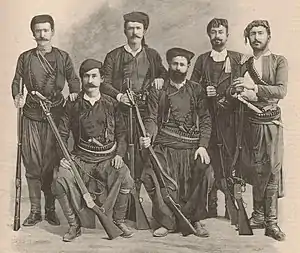

Cretan rebel leaders in early 1897 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Background

Previous revolts

The conquest of Crete by the Ottoman Empire ended in 1669 with the capture of Candia. Crete then became an Ottoman province.

In 1821, the Greek War of Independence in 1821 resulted in Greece achieving independence from the Ottoman Empire. The majority Greek Christian population of Crete now began aspiring to a union with the new Greek nation. The Greek Cretans revolted from 1866 to 1869, in 1878, but were crushed by Ottoman forces.

Cretan Greek activism

On February 3, 1895 (Julian), representatives of the Cretan provinces (Apokoronas, Kydoniai, Sphakia, Rethymno and Aghios Vasileios) met in Klema, near Chania. They drafted a memorandum to the Government of Greece and several of the so-called Great Powers in Western Europe. The representatives called for the Ottomans to appoint a Christian governor for Crete. They requested that the European powers put Crete under their protection. After the mass killing of Christian Armenians in Anatolia by Ottoman forces in 1895, public opinion in Europe became concerned that a similar catastrophe could happen to the Christian Greek population of Crete, forcing their governments to get involved in the Crete conflict.

To show goodwill to the European powers, the Ottomans replaced the Muslim governor with a Christian, Alexander Karatheodoris. However, the Karathodoris appointment alarmed Muslim Turkish Cretans, who feared rule under the Christian Greek Cretans. A pan-Cretan rebel group emerged that massacred Greeks to force his resignation. In response, Greek groups organized guerrilla warfare and retaliated against Turks.

The Cretan assembly also called for the reinstatement of the clauses of the Halepa Pact of 1878, which were favourable to Christians. In response, Karatheodoris dissolved the Cretan assembly on June 18, 1895.[5]

Cretan unrest 1895 to 1896

In September 1895, the Greek Cretans formed a revolutionary assembly at the instigation of the Consul General of Greece. It met in Krapi on 10 September. The revolutionary assembly demanded the declaration of Crete as an autonomous entity, paying an annual tribute to the Ottomans. This autonomous Crete was to be governed by a Christian governor, appointed for five years, without the Ottomans having the right to replace him. The rights granted by the Halepa Pact were to be restored and improved.

In response, Karatheodoris ordered the arrest of the revolutionary assembly members. On November 27, 1895, armed conflict broke out at Vryses between Greek Cretan members of the "Transition Committee" and 3,000 Ottoman troops commanded by Tayyar Pasha. After a day long battle, the Greek Cretans forced the Ottoman troops to retreat after losing 200 men and failing to capture any assembly members.

In March 1896, Karatheodoris was replaced by Turhan Pasha Përmeti as governor of Crete.[6] Përmeti declared a general amnesty as part of a peace initiative, but the revolutionary assembly rejected it.[7]

On May 4, 1896, Greek Cretans laid siege to the Ottoman garrison at Vamos, capturing it on May 18.[7] On May 11, Turkish Cretens starting robbing and killing Christians in Chania, later extending the violence to Kydonia and Kissamos.

In November 1866, a large Ottoman force besieged the Arkadi Monastery, which was the headquarters of the rebellion. In addition to its 259 defenders, over 700 women and children had taken refuge there. After a few days of hard fighting, the Ottomans broke into the monastery. At that point, the abbot set fire to the gunpowder stored in the monastery's vaults. The explosion killed most of the rebels and the women and children.

In response to the Arkadi attack, the Greek government sent volunteer fighters to Crete to protect the Greek communities. In May 1896, France and the United Kingdom moved a naval force to Cretan waters.

Crete constitution - 1896

To end the fighting in Crete, the consuls of the European powers proposed a new constitution for Crete to the Ottomans and the revolutionary assembly. The constitution called for the Ottomans to:

- appoint, with great power approval, a Christian governor of Crete to serve a five-year terms.

- reserve twice as many jobs for Christians as for Muslims

- reorganize the Cretan gendarmerie and staff it with European officers

- recognize the full economic and judicial independence of Crete under the protection of the great Powers.

Both sides accepted the new constitution and fighting in Crete ended in August 1896. In September, the Ottomans appointed George Berovich Pasha, former governor of Samos, as the new wāli (governor-general) of Crete.[8]

The revolt

January 1897

Within a month of Verovich Pasha's appointment, sectarian violence began increasing in Crete. The public prosecutor Kriaris was murdered in Chania and threats were made against the Christian community.[8]

In January 1897, Turkish rebels burned the residence of the Bishop of Chania along with the Christian neighborhoods in that city. Eleftherios Venizelos, reportedly said: "I saw Chania in flames. It was set on fire by the Muslims who thus triggered the great revolt."

Venizelos organized a camp in the Akrotiri peninsula establishing an Assembly of Crete and a provisional government. He located the camp near the Bay of Souda so that he could communicate easily with the admirals of the European fleets. Akrotiri's insurgents quickly hoisted the Greek flag and proclaimed the annexation of the island by Greece.

In early 1897, an international expeditionary force was sent to Crete on ships from France, the United Kingdom, Austria-Hungary, the German Empire, the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy.

Greek intervention

In February 1897, prime minister of Greece Theodoros Diligiannis ordered a military intervention in Crete. Yielding to pressure from the opposition and public opinion, he placed Prince George of Greece at the head of a fleet tasked with blockading Ottoman ships from supplying Crete. On February 11, 1897, 300 Greek volunteers and 800 boxes of ammunition arrived from Greece at the Greek Cretan camp on Akrotiri. On February 13, Cretan insurgents attacked Chania from the heights of Halepa. That same day, British Admiral Harris, suspecting the Greeks of supply the insurgents, forced Prince George to return to Greece.

Deligiánnis also sent a force of 1,500 men, led by colonel Timoleon Vassos, to take military control of Crete.[8] This army landed at Kolymbari[8] on February 16, and immediately declared the union of Crete with Greece. Vassos established his headquarters in Platania Alikianos.

On February 19, a group of 600 men, composed of Cretan rebels and volunteers along with Greek soldiers, stormed and captured the Turkish fortress of Voukolias.

European reaction

After the capture of Voukolias, the European Powers demanded a ceasefire. To back up their demands, they threatened to stop resupply of Vasso's army from Greece. Vassos said that he would not enter the four cities where the European fleets were present, but that his intention was to occupy the rest of Crete.

On 21 February, the Akrotiri camp was shelled by the European fleets. Their exact target was Venizelos' headquarters hill of the Prophet Elijah. These ships included the British HMS Revenge, HMS Dryad and HMS Harrier, the Russian ship Imperator Aleksandr II, the German SMS Kaiserin Augusta and the Austro-Hungarian SMS Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia

According to Kerofilas, the purpose of this bombing was to shoot down the Greek flag flying over Akrotiri. The fleet sent the rebels received a final ultimatum to remove the flag. Venizelos himself replied: "You have cannons. Pull! But our flag will not fall." According to account, a young Greek Cretan threw himself in front of the bombs and raised the banner, provoking the admiration even of the European admirals.

March 1897

In March 1897, the French and British fleets settled in positions opposite Akrotiri, making the blockade even stricter. On 10 March, Venizelos received the French, Italian and British admirals.[9][10]

Faced with the Cretan problem, the European powers had three solutions:

- the full restoration of Ottoman authority,

- the union of Crete with Greece (a solution favoured by European public opinion and the press)

- autonomy for Crete under the Ottoman Empire

Germany initially proposed to blockade the port of Piraeus, thus forcing the Greek army in Crete to withdraw, a solution rejected by Great Britain.

The British formulated the idea of autonomy, which would prevent the annexation of the island by Greece and thus preserve the principle of Turkey's integrity. On March 15 the European powers sent Greece their proposal for autonomy for the island. The Greek Government, driven by public opinion, categorically rejected this solution.

Onn March 20, the European powers declared the autonomy of Crete, placed under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire and, with their fleets, blockaded the island from the 21st. The admirals learned that the occupants of an Ottoman fort in Malaxa were on the verge of starvation after they had found themselves surrounded by the Cretans, despite the white flag hoisted for several days. Two days later, the admirals sent the Greek Cretans request for withdrawal on pain of bombardment. Faced with a new refusal by the Cretans, the admirals had difficulty, this time, to go on the offensive.

Political developments - April 1897 to July 28, 1897

Ottoman intervention

On April 17, 1897, the Ottoman Empire officially declared war on Greece. On hearing the news, many of the Greek volunteers at Akrotiri' wanted to return to face a possible Ottoman invasion. On 9 May, Vassos returned to Greece with them. A few days later, Greece defused the crisis with the Ottoman Empire by renouncing any plans to annex Crete.

On 13 May, Venizelos declared that he and his forces would not lay down their arms until the last Ottomon soldier had left the island, so the conflict continued. .

On July 10, 1897, in Armeni, Sphakiannakis was elected president of the revolutionary assembly. His plan was to organize a government for the island, headed by a prince of a European royal family, chosen by the European powers and approved by the Ottomans. In August, Eleftherios Venizelos took the lead of the assembly, now meeting in Acharnes. In November, the revolutionary assembly became the Cretan Assembly.

Towards the end of 1897, the Ottomans decided to send 5,000 reinforcements to Crete, but they were blocked by the European powers,

At the same time, Russia proposed that Prince George of Greece be named governor of Crete. Great Britain and France supported George, but Germany and Austria-Hungary rejected him.

Peace agreement

On March 16, 1898, Germany announced that it was withdrawing from Crete and would not oppose or approve the choice of Prince George as governor. The next day, the ship Oldenburg left Chania. On April 12 Austria-Hungary also dropped opposition to Prince George,

The remaining European powers now organized an administrative council on Create and asked for the gathering of Ottoman troops in certain points of the island. The admirals in turn asked their respective governments for the withdrawal of these troops. On 1 July, the administrative council of admirals gave the Cretan Assembly the power to elect an executive committee. On the 28th, a committee of five members was elected, including Venizelos. The seat of government, also chosen by the admirals in Halepa,

Ottoman withdrawal from Crete

In September 1898, the European admirals decided to collect taxes to support the new administration in Crete. On September 15, the Turkish governor of Candia refused to accept the collection without having received the order from Constantinople.

After three days of talks, a detachment of British troops tried to take the governor's premises by force. They were besieged inside the palace and massacred. The Turkish population then went to the residence of the British vice-consul, set it on fire, and killed him During this riot, fourteen Britons and 500 Cretans were killed, and many others wounded.

On 17 October 1898, Great Britain and the other European allies issued an ultimatum to the Ottoman government to withdraw Its troops and citizens from Crete within 30 days.

The majority of Cretan Turks left Crete at 1898.[11]

Autonomy of Crete

On 25 November the representatives in Athens of France, Italy, Great Britain and Russia proposed to King George I of Greece the appointment of his son Prince George as High Commissioner of Crete.[12] The proposal was for an appointment for three years, during which the prince must pacify the island and provide it with an administration. He had to recognize the Ottoman sovereignty over the island and let the Ottoman banners float over the fortresses. Each of the four protecting nations granted a loan of one million francs to the new High Commissioner to carry out his task.

Prince George arrived in Crete on 9 December, welcomed by the admirals of the European fleets. At this point, the revolt was over.

Aftermath

Prince George's government appointed a sixteen-member committee (twelve Christians and four Muslims) to draft a constitution, the first on the island. The Constitution of the Cretan Assembly was adopted on 9 January 1899. Elections were held for 138 Christian deputies and 50 Muslim deputies.

In the spring of 1905, an insurrection broke out against the Cretan government. It was led by Venizelos, who denounced the corruption of Prince George's entourage and the latter's inability to make the great powers accept the idea of annexation of Crete by Greece.

The beginning of the First Balkan War in 1912 opened the doors of the Greek Parliament to Cretan deputies, but did not yet mean formal union. On December 1, 1913, Crete received international recognition as a province of Greece.

References

- "The 1897 Revolution in Crete and Spiros Kayales". www.explorecrete.com.

- McTiernan 2014, p. 36.

- Holland, Robert, and Diana Markides, The British and the Hellenes: Struggles For Mastery in the Eastern Mediterranean, 1850–1960, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-19-924996-1, p. 92.

- McTiernan 2014, p. 28.

- Kallivretakis, Leonidas. A Century of Revolutions: The Cretan Question between European and Near Eastern Politics (in: Paschalis Kitromilides: Eleftherios Venizelos. The Trials of Statesmanship). Edinburgh University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0748624782 pages 27 - 30.

- Detorakēs 1994, p. 361.

- Detorakēs 1994, p. 362.

- Detorakēs 1994, p. 364.

- Dimitrov, Strashimir; Krastyo Manchev (1999). History of the Balkan peoples. Volume 2. pp. 76–79. ISBN 954-9536-19-X.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Encyclopaedia Britannica: Greco-Turkish Wars (accessed 26.04.2015)

- Tuncay Ercan Sepetcioglu (January 2021). "Cretan Turks at the End of the 19th Century: Migration and Settlement (19. Yüzyılda Girit Türkleri: Göç ve Yerleşim)" – via ResearchGate.

- Barchard, David. The Clash of Religions of Nineteenth Century Crete, с. 18 – 19

Sources

- McTiernan, Mick (2014). A Very Bad Place Indeed For a Soldier. The British involvement in the early stages of the European Intervention in Crete. 1897 - 1898. King's College London.

- Clowes, William Laird (1996). The Royal Navy: A History From the Earliest Times to the Death of Queen Victoria. Vol. 7. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-016-7.

- Detorakēs, Theocharēs E. (1994). History of Crete. Detorakis. ISBN 9789602207123.

- An Index of events in the military history of the Greek nation., Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate, Athènes, 1998.

- S. M Chester, Life of Venizelos, with a letter from His Excellency M. Venizelos., Constable, Londres, 1921.

- Teocharis Détorakis, A history of Crete, Heraklion, 1994

- C. Kerofilias, Eleftherios Venizelos, his life and work., John Murray, 1915.

- Paschalis M. Kitromilides, Eleftherios Venizelos : the trials of statesmanship., Institute for Neohellenic Research, National Hellenic Research Fondation, 2006.

- Jean Tulard, Histoire de la Crète, PUF, 1979