Epirus Revolt of 1854

The 1854 revolt in Epirus was one of the most important of a series of Greek uprisings that occurred in Epirus during that period. When the Crimean War (1854–1856) broke out, many Epirotes, with tacit support from the Greek state, revolted against the Ottoman rule. Although this movement was supported by distinguished military personalities, the correlation of forces doomed it from the start, leading to its suppression after a few months.

Background

When the Crimean War broke out between the Ottoman Empire and Russia, many Greeks felt that it was an opportunity to gain lands inhabited by Greeks but not included in the independent Kingdom of Greece. The Greek War of Independence (1821–1829) was still fresh in their minds, as well as the Russian intervention that had helped secure Greek independence. Furthermore, Greeks had traditionally looked to help from fellow-Eastern Orthodox Russia.

Although the official Greek state, under severe diplomatic and military pressure from the British and French (allies of the Ottomans), refrained from actively entering the conflict, a number of uprisings were organized in Epirus, Thessaly, Crete, with support from individuals and groups within independent Greece.

Uprising

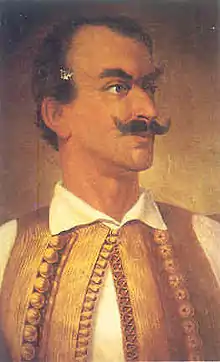

On 30 January 1854, Spyridon Karaiskakis (a Lieutenant in the Greek Army and son of the hero of War of Independence, Georgios Karaiskakis), gave a number of inspiring speeches in villages east of Arta (Peta region),[1] seeking to inspire the Epirotes to revolt against Ottoman rule and join their province to Greece. The initial objective was the provincial capital, Arta, which was captured by Karaiskakis with a force of 2,500 irregulars. In the meantime, the Greek General Theodoros Grivas took a band of 300 volunteers to the villages of Peta and Pente Pigadia.[2] Apart from the region of Arta, in Tzoumerka, the revolt also spread to most of the mountainous regions of Epirus and a number of towns soon came under the full control of the revolutionaries: Paramythia, Souli, Tsamantas, Himara and some villages around Ioannina.[3][4] The revolt was also in full swing in parts of the nearby region of Thessaly.

Meanwhile, a number of Greek officers, most of them of Souliote descent (Nikolaos Zervas, Notis Botsaris, Athanasios Koutsonikas, Kitsos Tzavelas, Lambros Zikos), resigned from their posts in the Greek Army and joined the rebellion. However, a unit of 1,600 Ottoman troops, reinforced by an additional 3,000, managed to recapture Arta with the help of heavy artillery.[5]

In early March, Grivas managed to advance further north capturing Metsovo which was afterwards looted by the Greek troops.[6] At March 27, after repeated Ottoman attacks, supported by Albanian irregulars, Grivas had to retreat. As a consequence the town of Metsovo was looted by these bands and a large part of it was burned down.[7][8]

Suppression

On April 13, a 6,000-strong Ottoman force, with the support of British and French artillery, attacked the rebels’ headquarters east of Arta, in the town of Peta. After fierce battles and suffering heavy losses, Kitsos Tzavelas with his men retreated behind the Greek border.[9][10] Meanwhile, the Ottomans moved north to eliminate every movement in the region around Ioannina. In Plaka, a force of 14,000 Ottomans with an addition of 1,500 Albanians fought against the armed groups of S. Karaiskakis and N. Zervas. The Ottoman force was forced to retreat, with the Albanians in particular suffering heavy losses.[11]

The situation started to worsen for the Greeks when additional Ottoman reinforcements arrived in the region. On the other hand, the British and the French forces blockaded the port of Piraeus and a number of other Greek ports, making reinforcement and ammunition for the revolutionaries hard to obtain and applying further pressure on the Greek government to force the return of its officers. After a number of vicious battles in Voulgareli, Skoulikaria and in Kleidi on 12 May, the revolt was doomed and the Epirotes retreated behind the Greek border.[12]

When the revolt in Epirus was finally suppressed, reprisals started, with Ottoman and Albanian bands looting and burning a number of towns and villages. These activities ended with the end of the Crimean War in 1856.[13]

References

- Reid 2000: 249

- Reid 2000: 249

- Sakellariou 1997: 288

- Badem, Candan (15 September 2021). The Routledge Handbook of the Crimean War. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-429-56096-5.

- Sakellariou 1997: 289-290

- Hammond, Nicholas (1976). Migrations and invasions in Greece and adjacent areas. Noyes Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-8155-5047-2.

- Sakellariou 1997: 290

- Ruches 1967: 73

- Sakellariou 1997: 290

- Reid 2000: 250

- Sakellariou 1997: 290

- Sakellariou 1997: 291

- Sakellariou 1997: 291

Sources

- Reid, James J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: prelude to collapse 1839-1878. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07687-6.

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- Ruches, P.J. (1967). Albanian Historical Folksongs. Argonaut.

Further reading

- George, Dodd (1856). Pictorial history of the Russian war 1854-5-6: with maps, plans, and wood engravings. W. & R. Chambers.

- New monthly magazine Vol. 102. Published for Henry Colburn by Richard Bentley. 1854.

- Der Aufstand der Griechen im Epirus, ihr Land, ihre Sitten u. Gebräuche, ihre Lage unter der türkischen Regierung: Mit einer Karte. Hartleben. 1854. [The Revolution of the Greeks in Epirus: their Land, Customs and Habits]. (German)