Cumbrian Coast line

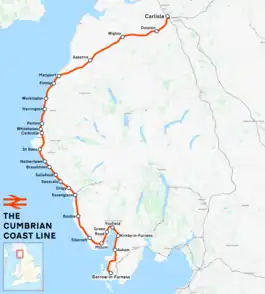

The Cumbrian Coast line is a rail route in North West England, running from Carlisle to Barrow-in-Furness via Workington and Whitehaven. The line forms part of Network Rail route NW 4033, which continues (as the Furness line) via Ulverston and Grange-over-Sands to Carnforth, where it connects with the West Coast Main Line.

| Cumbrian Coast Line | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overview | |||

| Status | Operational | ||

| Owner | Network Rail | ||

| Locale | Cumbria | ||

| Termini | |||

| Stations | 26 | ||

| Service | |||

| Type | Heavy rail | ||

| System | National Rail | ||

| Operator(s) | Northern Trains | ||

| Rolling stock | |||

| History | |||

| Opened | 1844 | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 85.5 mi (137.6 km) | ||

| Number of tracks | 2 (three sections of single track) | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) | ||

| |||

Cumbrian Coast line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

George Stephenson favoured, and carried out preliminary surveys for, a scheme to link England and Scotland by a railway running along the coast between Lancaster and Carlisle, but this 'Grand Caledonian Junction Railway' was never built, the direct route over Shap being preferred. Consequently, the line along the Cumbrian coast is the result of piecemeal railway building (largely to serve local needs) by a number of different companies:

Maryport and Carlisle Railway

Promoted to link with Newcastle and Carlisle Railway to give "one complete and continuous line of communication from the German Ocean to the Irish Sea" and to open up the northern (inland) portion of West Cumbrian coalfield. Act of Parliament obtained 1837; first section – Maryport to Arkleby (just short of Aspatria) – opened 1840: line Maryport–Carlisle fully opened 1845. Originally laid single; doubled throughout (to accommodate heavy and profitable mineral traffic) by 1861. Remained independent (and highly profitable) until grouping.

Whitehaven Junction Railway

Maryport to Whitehaven (Bransty)[2] (leased by London and North Western Railway 1865; amalgamated with LNWR 1866).

Whitehaven at this time was dominated by the Lowther family, and its head the Earl of Lonsdale. Attempts supported by William Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale to promote a 'Whitehaven, Maryport and Carlisle Railway' in 1835,[3] had lost out to the Maryport and Carlisle Railway. In 1844 a more limited project for a railway between Whitehaven and Maryport (supported by Lord Lonsdale and both MPs for West Cumberland) got its parliamentary Act.[4] The first Earl had died earlier in 1844, and it was his son, the second Earl, who became chairman of the company and remained so throughout its existence. The line was opened from Maryport to Workington at the end of November 1845,[5] and to Harrington mid-May 1846[6] Between Whitehaven and Harrington the line ran between cliffs and the sea and landslips, rockfalls, and high tides made construction problematical. A train ran all the way from Maryport to Whitehaven on 19 February 1847, but the passengers left it at Harrington;[7] the line opened for passenger traffic 18 March 1847.[8]

In 1848 two Acts were obtained; one to authorise the raising of further capital to cover overspend on the construction of the existing line, one to make the link with the Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway (W&FJR) by an elevated railway running to the harbour and then along the harbour front.[9] The harbour link was never built (the W&FJR deciding to proceed with their original intention of a tunnel) but lines were laid down to serve the North Pier.[10] There were continuing difficulties with the sea walls on the Whitehaven-Harrington section, which were now described as of bad and inefficient design and executed in a worse and more objectionable manner;[11] in 1851 the seawall was rebuilt at Harrington and Lowca at a cost of £6000. However, when in January 1852 a storm badly damaged the seawall immediately north of Whitehaven station (the wall, the embankment behind it, and the railway track being completely destroyed for a length of about fifty yards,[12]) the damaged section pre-dated the railway.[13] A further storm in December 1852 caused more extensive damage, the repaired section being lost again as a consequence of failure of the old wall immediately north of it (there were further wash-outs at Lowca and Risehow), but services were resumed within a fortnight.[14] The link to the WJR from the W&FJR was made (as originally intended) by a tunnel, completed at the end of September 1852; a joint working agreement with the W&FJR took effect at the start of 1854.[15] In December 1855, Bransty station shut for goods business and the Preston Street station of the W&FJR became the WJR's goods station for Whitehaven.[16]

In 1856, the company secretary was replaced after an audit suggested about £3,000 had gone missing (the loss was made good by 'the directors' -in fact Lord Lonsdale alone – from his own pocket), and the company engineer resigned because of the defective state of the engines and the inefficiency of previous repairs[17] but the WJR was entering an era of prosperity (by 1864 it was declaring a dividend of 15%)[18] largely because of a boom in haematite mining. It was reported that in 1856, the quantity of iron ore raised in the neighbourhood of Whitehaven was 259,167 tons. Of this 152,875 was shipped at Whitehaven, 65,675 sent away by rail, and 39,617 tons used at the iron works in the district. The destinations of the ore were as follows: – Wales, 124,630 tons; Staffordshire 26,768 tons; Scotland 15,865 tons, Newcastle, Middlesbro &c, 51470 tons; and to France 817 tons.[19]

A branch to the wet dock at Maryport opened September 1859[20] and carried considerable traffic from collieries at Flimby; the line (hitherto single throughout) was widened from Maryport to Flimby[lower-alpha 1] and doubled throughout by 1861.[22] The original Railway Hotel at Bransty was bought for use as station buildings and offices for the two Whitehaven companies, the Cockermouth and Workington Railway's half-share of Workington station was bought out, and timber viaducts at Workington and Harrington were replaced, the Board of Trade objecting to the use of timber in the Harrington replacement, especially given the WJR's prosperity: "The continued use of this material in the present instance by the directors of a company ... whose receipts are ... £53 per mile per week is quite inexcusable."[23] The WJR reached an agreement (1864) with the Cockermouth and Workington to lease the C&WR, guaranteeing a 10% dividend to C&WR shareholders, but did not get parliamentary approval for the necessary Bill, the Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway objecting that the lease would obstruct any movement of ore northwards except over the WJR[24] The WJR then (June 1865) reached agreement with the London and North Western Railway for the LNWR to lease the WJR in perpetuity, paying 10% a year.[25] (The LNWR reached a similar agreement with the Cockermouth and Workington, and the Furness Railway with the W&FJR); the Bill making the amalgamation permanent received its royal assent in July 1886.[26] In the first six months of operation by the LNWR, the profit on the line was said to be 27% a year.[27]

When the Whitehaven – Harrington section was first opened the Carlisle Journal – politically opposed to the Lowther interest – had criticised it : "Zig-zag, zig-zag, zig-zag, perpetually. No serpent wriggles in more contortions than the Whitehaven Junction Railway" and pointed out the horrors of an accident on such a corniche "The poor wretches who fill the train must either have their brains dashed out against the rocks at one side or be pitched head-foremost into the sea on the other"[28] Train crew could never see far ahead, and there was always the possibility of a rockfall onto the track: even after the doubling of the line, the Board of Trade required a speed limit of 15 mph on the section. In 1860, whilst the section was still single-track, a heavy iron-ore train broke down on this section and a mistake by the station-master at Whitehaven led to a low-speed collision between a portion of the train being returned to Whitehaven and a passenger train advancing to push the failed train to Harrington. Sixteen passengers were injured, two seriously;[23] the accident (together with another low-speed collision in 1862)[29] was said to have cost the WJR about £20,000 in compensation alone,[30] and the vulnerability of the WJR dividend to any further accident was one of the arguments adduced in support of the lease to the LNWR.[25][lower-alpha 2]

Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway

Whitehaven to Foxfield[32] (leased by Furness Railway 1865, amalgamated 1866).

The first Earl of Lonsdale had supported the idea of a railway linking Whitehaven to Maryport, but had had no interest in building a railway south of Whitehaven, let alone one linking to the West Coast Main Line : however he died in 1844 and was succeeded by his son William Lowther, 2nd Earl of Lonsdale who supported the scheme and under his chairmanship the Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway obtained its Act in the next session of Parliament.[33] and in 1846 a further Act[34] for extension of the W&FJR to a junction with the WJR near the latter's Whitehaven station. There was little potential local traffic, and the hope was for the through traffic which would flow once the W&FJR was extended to a junction with the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway south of Carnforth. However a Bill for that extension was rejected because of inconsistencies in its documentation [35][lower-alpha 3] and it was left to others to provide a link between Lancaster and Furness, and to Lord Lonsdale to nurse the company until better times arrived.[40]

By 1847, the company was becoming concerned that remaining funds would be insufficient to tackle the remaining expensive engineering (the tunnel to reach the Whitehaven station of the WJR and a 2-km long viaduct across the Duddon estuary to join the Furness Railway near Kirkby Ireleth).[41][lower-alpha 4] In 1848 Bills were brought forward to make the link with the WJR by an elevated railway running to the harbour and then along the harbour front and for abandoning the Duddon crossing to Kirkby Ireleth, the line instead turning back on itself to follow the west bank of the Duddon estuary upstream to a much shorter crossing to a junction with the Broughton-in-Furness branch of the Furness Railway at Foxfield.[44]

The 16 km section of line from Mirehouse (2 km south of Whitehaven) to the River Calder, already used for construction traffic, was used to move coal to depots at Braystones and Sellafield in February 1849,[45] marking its opening for goods traffic. The first passenger services between a temporary station at Preston Street (at the southern edge of Whitehaven) and Ravenglass followed an official opening on 21 July 1849.[46][lower-alpha 5] Bootle became the southern terminus of passenger services in July 1850:[48] the last section between Bootle and Foxfield was opened for passenger services 1 November 1850[49] although trains carrying Lord Lonsdale and invited guests had travelled from Whitehaven to Broughton-in-Furness over the section on at least two previous occasions. The link to the WJR station at the north of the town was made (as originally intended) by a tunnel, completed at the end of September 1852. A tramway through the market place allowing goods waggons to be horse-drawn from Preston Street to the south end of the harbour,[50] authorised by an Act of 1853 was completed in 1854;[51] a joint working agreement with the WJR took effect at the start of 1854.[15] From December 1855 W&FJR passenger trains ran to the WJR station at Bransty;[lower-alpha 6] Preston Street became the goods station for both lines and a passenger station was opened at Corkickle, immediately south of the tunnel.[53] The goods portion of north-bound mixed trains was detached some distance from Corkickle and run into Preston Street under gravity.[54]

The opening of the Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway brought considerable additional mineral traffic onto the W&FJR at its northern end:[55] at the southern end, a through route southward from Whitehaven was finally achieved with the completion of the Ulverstone and Lancaster Railway in 1857,[56] reflecting this an additional curve was laid down at the junction with the Furness Railway and W&FJR trains ran to Foxfield or Ulverston rather than Broughton. To facilitate the export of haematite southwards, in 1864 the W&JR (now paying a previously unheard-of 8% dividend) projected a direct crossing of the Duddon estuary (to eliminate the dog-leg through Foxfield) in competition with a similar proposal by the Furness Railway; disagreement with the Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont as to who should build a line from the WC&ER at Egremont to the W&FJR at Sellafield was deferred by the W&FJR's charges being reduced, and both companies (temporarily) dropping their plans to build the line,[57] subsequently agreeing to promote as a joint line.[58] The WW&FJR got its Bill for the Duddon crossing, but then agreed to be leased by the Furness Railway for a guaranteed 8% a year.[59]

Furness Railway

Foxfield to Barrow-in-Furness.[60]

Incorporated 1844; promoted by Duke of Buccleuch and Earl of Burlington (later Duke of Devonshire) to link iron ore mines (at Dalton-in-Furness) and slate mines (at Kirkby-in-Furness) with Barrow harbour. Open Barrow- Kirkby in 1846, extended to Broughton in Furness 1848.

All the above constituents were absorbed into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway in 1923.

Current passenger services

Train services are operated by Northern. Services stop at all stations (although many are request stops), with the exceptions of Nethertown and Braystones, which are served by four trains a day in each direction and Drigg, Bootle and Silecroft, which are not served by 1 train per day in each direction.

In the December 2022 – May 2023 timetable,[61] the following trains operated on weekdays:

- Southbound – 24 trains per day

- Carlisle to Barrow-in-Furness – 15 trains per day, of which 3 continue to Lancaster and 1 to Preston

- Carlisle to Whitehaven – 4 trains per day

- Maryport to Barrow-in-Furness – 1 train per day

- Sellafield to Barrow-in-Furness – 1 train per day

- Millom to Barrow-in-Furness – 3 trains per day

- Northbound – 26 trains per day

- Barrow-in-Furness to Carlisle – 17 trains per day, of which 4 begin at Lancaster

- Barrow-in-Furness to Millom – 2 trains per day, of which 1 begins at Lancaster

- Barrow-in-Furness to Sellafield – 1 train per day

- Whitehaven to Carlisle – 4 trains per day, of which 1 begins at Workington

- Whitehaven to Maryport – 1 train per day

There are no trains after 19:30 each evening between Millom and Whitehaven, as this section is only open for 12 hours each day due to the high operating costs associated with the large number of signal boxes and staffed level crossings that are present. Services are slightly altered on Saturdays and on Sundays there are less trains.

A new Sunday service was introduced in the May 2018 timetable change[62] over the section south of Whitehaven after the new Northern Rail franchise agreement came into effect in April 2016 – the old operator (Arriva Rail North Ltd) also running an additional six weekday trains each way as part of the 10-year agreement with the Department for Transport.[63]

In the December 2022 – May 2023 timetable,[64] the following trains operated on Sundays:

- Southbound – 14 trains per day

- Carlisle to Barrow-in-Furness – 7 trains per day, of which 2 continue to Lancaster

- Carlisle to Whitehaven – 4 trains per day

- Maryport to Barrow-in-Furness – 1 train per day

- Millom to Barrow-in-Furness – 2 trains per day

- Northbound – 13 trains per day

- Barrow-in-Furness to Carlisle – 7 trains per day, of which 1 begins at Carnforth and 2 begin at Lancaster

- Barrow-in-Furness to Millom – 3 trains per day

- Whitehaven to Carlisle – 3 trains per day

At Carlisle the lines connects to the: West Coast Mainline; the Settle-Carlisle Line; the Tyne Valley Line; the Glasgow South Western Line; and the Caledonian Sleeper service. At Barrow, there are connections to the Furness Line.

Passenger rolling stock

Due to restricted clearances on the section of line between Maryport and Carlisle, as several overbridges were built to narrower than normal dimensions by the M&CR, Class 150's, Class 158's, Class 195's and many other diesel multiple units are banned from the route because of their width. Services are therefore operated by Class 156 units. The line has also been previously operated by Class 142 Pacer units, but these have since been phased out in favour of Class 156 Sprinters cascaded from Abellio ScotRail. Class 153's have also previously worked along the route but these are now off lease from Northern being replaced by Class 156's.

In the past, the Class 108 first generation DMUs, formerly used on the line, were custom-fitted with bars on the drop-light doors for this reason. Since 2006, Network Rail have eased clearance restrictions so as to allow Mark 1, Mark 2 and Mark 3 coaching stock to operate along the full route, although under strict instructions that all drop-light windows must be either stewarded or locked between Maryport and Carlisle to prevent passengers from putting their heads out of the windows. This has allowed many charter services to operate the full length of the Cumbrian Coast. In the May 2015 timetable change, a number of scheduled services between Carlisle & Barrow were operated using Mark 2 coaches, a DBSO and Class 37 diesel locomotives hired in from Direct Rail Services to provide additional seating capacity – these were modified accordingly which included placing bars across the droplight windows.[65] These workings reverted to DMU operation at the end of December 2018.[66]

It is mandatory that passengers remain in their seats whenever steam tours travel between Maryport and Carlisle in both north and southbound directions; this is because most West Coast Railways Mark 1 coaches, which are used by charter companies, don't have bars across the droplight windows. Steam railtours using the route had, until recently, been banned because of the restricted clearances as well as the fear of injury to members of the public. The width of some steam engines prohibits them from working along the routes, steam locos which have travelled along the route in recent years include: LMS Black 5's, LMS 8F's, LMS Jubilee's & LMS Royal Scot's.

The Cumbrian Coast was given Community Rail status in 2008 and has an active Community Rail Partnership working hard to develop the route.

Towns and villages along the route

- Carlisle

- Dalston

- Wigton

- Aspatria

- Maryport

- Flimby

- Workington

- Harrington

- Parton

- Whitehaven

- Corkickle

- St Bees

- Nethertown

- Braystones

- Sellafield

- Seascale

- Drigg

- Ravenglass

- Connection for the Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway (La'al Ratty)

- Bootle

- Silecroft

- Millom

- Green Road

- Foxfield

- Kirkby-in-Furness

- Askam-in-Furness

- Barrow-in-Furness

Route description

Network Rail's route NW 4033 runs for 114.3 mi (183.9 km) from Carnforth North Junction, near Carnforth, to Carlisle South Junction, near Carlisle, by way of Sellafield.

| NW 4033 | M-Ch | km |

|---|---|---|

| Carnforth North Junction | 0-00 | 0.00 |

| Carnforth | 0-12 | 0.25 |

| Carnforth Station Junction | 0-19 | 0.40 |

| Silverdale | 3-36 | 5.55 |

| Arnside | 6-10 | 9.85 |

| Grange-over-Sands | 9-12 | 11.85 |

| Kents Bank | 11-08 | 14.75 |

| Cark and Cartmel | 13-29 | 21.50 |

| Ulverston | 19-09 | 30.75 |

| Dalton | 23-46 | 37.95 |

| Dalton Junction | 24-19 | 39.00 |

| Roose | 26-74 | 43.35 |

| Salthouse Junction | 27-38 | 44.20 |

| Barrow-in-Furness | 28-66 | 46.40 |

| Park South Junction | 32-57 | 52.65 |

| Askam | 34-64 | 56.00 |

| Kirkby-in-Furness | 38-00 | 61.15 |

| Foxfield | 40-21 | 64.80 |

| Green Road | 42-15 | 67.90 |

| Millom | 44-68 | 72.20 |

| Silecroft | 47-73 | 77.10 |

| Bootle | 53-18 | 85.65 |

| Ravenglass | 57-60 | 92.95 |

| Drigg | 59-59 | 96.15 |

| Seascale | 61-73 | 99.65 |

| Sellafield | 63-57 | 102.55 |

| Braystones | 65-57 | 105.75 |

| Nethertown | 67-13 | 108.10 |

| St Bees | 70-03 | 112.70 |

| Corkickle | 73-59 | 118.65 |

| Whitehaven | 74-47 | 120.05 |

| Bransty Junction | 74-54 | 120.15 |

| Parton | 75-79 | 122.30 |

| Harrington | 79-08 | 127.30 |

| Workington | 81-27 | 130.90 |

| Workington North | ||

| Flimby | 85-00 | 136.80 |

| Maryport | 86-64 | 139.70 |

| Aspatria | 94-36 | 152.00 |

| Wigton | 102-63 | 165.40 |

| Dalston | 110-06 | 177.15 |

| Currock Junction | 113-37 | 182.60 |

| Carlisle South Junction | 114-19 | 183.85 |

2009 floods

In the aftermath of the 2009 floods, an extra hourly service between Maryport and Workington operated stopping at all stations in between, including the temporary Workington North. These services were withdrawn in December 2010.

Historical Connecting lines

The following lines all previously connected to the Cumbrian Coast Line, but have mostly now been closed

- Silloth branch, from Aspatria

- Brigham branch, near Maryport

- Cleator and Workington Junction Railway, near Workington

- Cockermouth and Workington Railway, near Workington

- Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway, near Corkickle[67] (this was the main connection: the Gilgarran branch of the WC&ER also connected at Parton).

- Cleator and Furness Railway, near Sellafield

- Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway, at Ravenglass. This is a narrow gauge railway which still runs services for tourists, but there was formerly a standard gauge line from Ravenglass to Murthwaite for freight.

- Coniston Branch, near Foxfield

- Sandscale branch, at Barrow in Furness

Notes

- apparently not so that 'up' and 'down' traffic had separate lines, but so that 'the coal traffic was worked independently of the passenger line': coal traffic had previously been conducted by a single 'coal engine' hauling 'specials' as timetabled traffic permitted [21]

- In 1866, the LNWR paid nearly £120,000 in accident compensation, but this was under half a per-cent of their receipts from passenger traffic.[31]

- The Bill claimed the line crossed various roads by overbridges – the accompanying plans and sections showed level crossings.[36] Joy[37] talks of the W&FJR intending a junction at Carnforth and not with the L&C, but with the "Little" North Western Railway (ie something much like what was eventually built) but this is at odds with the notice given of their 1846 Bills by both the W&FJR[38] and the NWR[39]

- the 'Railway Mania' had now passed, and great difficulty was anticipated in raising fresh capital – in 1848 it was estimated that of the 17,000 shares issued only about 11,000 were in the hands of solvent parties[42] and the part-paid shares were said to be unsaleable.[43]

- Locomotives and other rolling stock were man-hauled to Preston Street from the terminus of the WJR on moveable rails set down in the streets of Whitehaven – in the process a King Street jeweller had his foot trapped under a rail and his left leg nearly amputated by an engine outside his front door, later dying of his injuries[47] – the account in Joy[37] which has the accident occurring on 14 July, and on a link via the harbour clearly has problems. A further fatal accident soon followed; a train approaching Preston Street did not slow adequately, went clean through the railway premises and buried itself in a house beyond,killing a ten-year-old girl

- They had to reverse into it; the current through platform at the north end of the tunnel did not exist until the station was remodelled by the LNWR in 1874, and the original WJR platforms were virtually on Bransty Row[52]

References

- "Maryport and Carlisle Railway". RailScot. 24 March 2012.

- "Whitehaven Junction Railway". RailScot. 2 April 2012.

- "Whitehaven, Maryport and Carlisle Railway (advertisement)". Carlisle Patriot. 12 December 1835. p. 2.

- "Local Intelligence". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 9 July 1844. p. 2.

- "Railway Intelligence – Local – Partial Opening of the Whitehaven Junction Railway". Carlisle Patriot. 14 November 1845. p. 3.

- "Railway News". The Daily News. London. 2 September 1846. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Opening of the Whitehaven Junction Railway". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 24 February 1847. p. 2.

- "Opening of the Whitehaven Junction Railway". Carlisle Patriot. 19 March 1847. p. 2.

- "Whitehaven Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 29 August 1848. p. 4.

- "Whitehaven". Carlisle Journal. 21 February 1851. p. 2.

- "Whitehaven Junction Railway – Half-Yearly Meeting". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 26 August 1851. p. 4. – they had been built using common mortar which did not withstand constant wetting

- "Extraordinary Railway Disaster". Carlisle Patriot. 31 January 1852. p. 3.

- "Whitehaven Junction Railway". Carlisle Patriot. 21 February 1852. p. 3.

- "The Whitehaven Junction Railway Company". Carlisle Patriot. 19 February 1853. p. 4. – Lord Lonsdale said the December 1852 storm was the most severe since 1826

- "Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway Meeting". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 28 February 1854. p. 4.

- "Whitehaven Junction Railway – Notice (advertisement)". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 25 December 1855. p. 8.

- "Whitehaven Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 26 August 1856. p. 5.

- "Local Railway Meetings". Whitehaven News. 1 September 1864. p. 4.

- "Iron Ore Produced in West Cumberland and Furness". Lancaster Gazette. 14 November 1857. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

quoting "from the memoirs of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, by Robert Hunt, F.R.S." – presumably Hunt, Robert (1857). Memoirs of the Geological Survey of Great Britain and of the Museum of Practical Geology: Mining records: Mineral statistics of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for the year 1856. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016 – via USGS Publications Warehouse.

quoting "from the memoirs of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, by Robert Hunt, F.R.S." – presumably Hunt, Robert (1857). Memoirs of the Geological Survey of Great Britain and of the Museum of Practical Geology: Mining records: Mineral statistics of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for the year 1856. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016 – via USGS Publications Warehouse. - "Opening of the New Railway Branch Line at Maryport". Carlisle Journal. 16 September 1859. p. 5.

- Tyler, H.W. (Capt RE) (17 March 1858). "Accident Returns: Extract for the Accident at Flimby Colliery on 1st February 1858" (PDF). Railways Archive. Board of Trade. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "Whitehaven Junction Railway". Carlisle Journal. 11 October 1861. p. 5.

- Tyler, H.W. (Capt RE) (15 December 1860). "Accident at Harrington on 14th August 1860" (PDF). Railways Archive. Board of Trade. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "Whitehaven Junction and Cockermouth and Workington Railway". Carlisle Patriot. 11 March 1865. p. 6.

- "Whitehaven Junction Railway". Whitehaven News. 29 June 1865. p. 6.

- "Local Railways". Carlisle Journal. 27 July 1866. p. 9.

- "A Paying Railway". Carlisle Journal. 31 August 1866. p. 5.

- quoted in "Whitehaven Junction". Morning Post. 23 March 1847. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tyler, H.W. (Capt RE). "Accident at Whitehaven on 6th March 1862" (PDF). Railways Archive. Board of Trade.

- "Compensation Claims Against the Whitehaven Junction Railway". Carlisle Journal. 5 December 1865. p. 2.

- "London and North Western". Whitehaven News. 28 February 1867. p. 5.

- "Whitehaven and Furness Railway". RailScot. 2 April 2012.

- "Imperial Parliament". Carlisle Patriot. 25 July 1845. p. 4.

- "Local Intelligence". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 11 August 1846. p. 2.

- "Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway – Lancashire Extension (advertisement )". Kendal Mercury. 13 June 1846. p. 1.

- "Railway Memoranda". Kendal Mercury. 4 April 1846. p. 2.

- Joy, David (1993). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 14: The Lake Counties. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-946537-02-X.

- "Notice is Hereby Given". Westmorland Gazette. 29 November 1845. p. 4.

- "North Western Railway – Notice is Hereby Given". Westmorland Gazette. 29 November 1845. p. 4.

- his efforts are detailed (with no separate heading) in the editorial column of the (generally anti-Lowther) Whitehaven News: "Whitehaven News – Thursday September 1 1859". Whitehaven News. 1 September 1859. p. 2.

- "Railway Intelligence". Evening Standard. London. 27 August 1847. p. 4.

- "Whitehaven and Furness Junction". Carlisle Journal. 1 September 1848. p. 3.

- "Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway". Westmorland Gazette. 2 December 1848. p. 3.

- "Admiralty Inquiry". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 22 February 1848. pp. 3–4.

- "Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 27 February 1849. p. 3.

- "Opening of the Whitehan and Furness Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 24 July 1849. p. 4.

- "Shocking and Fatal Accident". Morning Post. 12 July 1849. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Opening of the Railway to Bootle". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 9 July 1850. p. 3.

- "Local Intelligence". Carlisle Patriot. 2 November 1850. p. 2.

- "Reports of Select Committees on Railways". Carlisle Journal. 17 June 1853. p. 5.

- "(untitled item in leader column headed) The Pacquet – Whitehaven – Tuesday 21st March 1854". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 21 March 1854. p. 2.

- "England and Wales Six-Inch Series: Cumberland LXVII". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. 1867. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- "Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway – Notice (advertisement)". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 25 December 1855. p. 1. – the advertisement speaks of 'the station at Preston Street' cf's Joy's claim that this name was only adopted c 1860

- "Fatal Accident on the Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 6 January 1857. p. 5.

- "Our Local Railways". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 8 September 1857. p. 4.

- "Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. 1 September 1857. p. 8.

- "Railway Intelligence – Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway". Whitehaven News. 2 March 1865. p. 7.

- "The Whitehaven Railways". Kendal Mercury. 17 March 1866. p. 4.

- "Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway". Whitehaven News. 31 August 1865. p. 8.

- "Furness Railway". RailScot. 11 March 2012.

- "Carlisle to Barrow-in-Furness". 11 December 2022.

- "August News". Copeland Rail Users Group. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "Northern Franchise Improvements – DfT". Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Carlisle to Barrow-in-Furness". 11 December 2022.

- "New Loco-hauled Services for the Cumbrian Coast". Rail Technology Magazine. 19 May 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Special Cumbrian service to commemorate Class 37s". Northern (Press release). 7 January 2019. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway". RailScot. 2 April 2012.