Cyclone Savannah

Severe Tropical Cyclone Savannah was a strong tropical cyclone that brought significant impacts to Java and Bali and minor impacts to Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands during March 2019. It was the sixteenth tropical low, sixth tropical cyclone and third severe tropical cyclone of the 2018–19 Australian region cyclone season. Savannah developed from a tropical low that formed well to the east of Christmas Island on 8 March. The system was slow to develop initially, but reached tropical cyclone intensity on 13 March after adopting a southwesterly track. Savannah underwent rapid intensification and reached peak intensity on 17 March as a Category 4 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian scale. Ten-minute sustained winds were estimated as 175 kilometres per hour (109 mph), with a central barometric pressure of 951 hPa (28.08 inHg). One-minute sustained winds reached 185 kilometres per hour (115 mph) at this time, equivalent to a Category 3 major hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Weakening commenced soon afterwards, and responsibility for the system passed from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology to Météo-France. As it moved into the new region, Savannah became the eighth of a record-breaking ten intense tropical cyclones in the 2018–19 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season. Savannah was downgraded to a tropical depression on 20 March, and its remnants dissipated in the central Indian Ocean on 24 March.

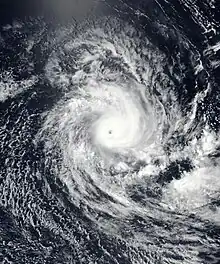

Severe Tropical Cyclone Savannah at peak intensity on 17 March 2019 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 8 March 2019 |

| Remnant low | 20 March 2019 |

| Dissipated | 24 March 2019 |

| Category 4 severe tropical cyclone | |

| 10-minute sustained (BOM) | |

| Highest winds | 175 km/h (110 mph) |

| Highest gusts | 250 km/h (155 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 951 hPa (mbar); 28.08 inHg |

| Category 3-equivalent tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 195 km/h (120 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 957 hPa (mbar); 28.26 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 10 |

| Missing | 1 |

| Damage | >$7.5 million (2019 USD) |

| Areas affected | Bali, Java, Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2018–19 Australian region and South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons | |

Savannah brought significant impacts to Java and Bali early in its lifetime. Prolonged heavy rainfall and river level rise led to widespread flooding and landslides throughout the region. Floodwaters impacted scores of villages, causing damage to thousands of homes, submerging thousands of hectares of agricultural land and cutting off access to key infrastructure and services. Thousands of families were affected during the event, with evacuations occurring both before and after the flooding. According to local media reports, the total damage and economic losses caused by the disaster exceeded Rp106 billion (US$7.5 million).[nb 1] Ten people were reported to have died during the event, making Savannah the deadliest tropical cyclone in the Australian region since Tropical Cyclone Cempaka in 2017. News reports also indicate that at least five people were injured and that one person went missing during the disaster.[nb 2]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

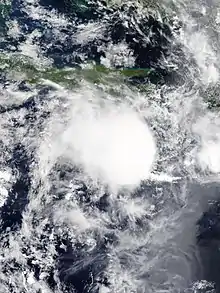

During early March, a moderate strength pulse of the Madden–Julian oscillation tracked eastwards across the tropical Indian Ocean and into the Maritime Continent.[15] The pulse brought with it weak monsoonal conditions to the north of Australia, as well as an atmospheric environment that was favourable for tropical cyclogenesis.[16] On 8 March, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) noted the formation of a weak tropical low (identifier 17U) within a monsoon trough stretching from Java to the Solomon Islands—one of several tropical lows that would develop within this trough.[16] Located south of Bali, Indonesia, and approximately 970 km (600 mi) east of Christmas Island, the nascent tropical low began moving slowly westwards.[17][18] Tracking roughly parallel to the southern coastline of Java, the system passed just to the south of Christmas Island at 06:00 UTC on 11 March, before turning to the northwest.[19]

The tropical low executed a poleward turn on 12 March, assuming a course to the southwest by the following day.[17] Tracking away from Indonesia, the storm began to strengthen in a generally favourable environment. The BOM upgraded the system to a Category 1 tropical cyclone on the Australian scale at 18:00 UTC on 13 March as it was approaching the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and gave it the name Savannah.[17][19] Six hours later, the United States' Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) indicated that the system had reached tropical storm strength on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale.[20] Intensification continued as Savannah passed approximately 110 km (68 mi) to the west of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and the system reached Category 2 late on 14 March.[17][19] Savannah became a Category 3 severe tropical cyclone the following day, and adopted a track to the west-southwest under the influence of a high-pressure ridge in the mid-troposphere further to the south.[17][21] The storm began to strengthen quickly on 16 March, reaching peak intensity as a Category 4 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian scale at 06:00 UTC the following day, making it the then-strongest storm of the 2018–19 Australian region cyclone season. The BOM estimated ten-minute sustained winds to be at 175 kilometres per hour (109 mph), gusting to 250 kilometres per hour (160 mph), with a central barometric pressure of 951 hPa (28.08 inHg).[19] The JTWC analysed the storm to be producing one-minute sustained winds of 185 kilometres per hour (115 mph), making the system equivalent to a Category 3 major hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale.[20]

Savannah soon began to weaken, with ten-minute sustained winds decreasing to 140 kilometres per hour (87 mph) twelve hours later. By 00:00 UTC on 18 March, the system tracked over the 90th meridian east and into the South-West Indian Ocean cyclone region, and hence responsibility for the storm transitioned to Météo-France (MFR) at La Réunion.[19] According to the scale used by MFR, Savannah was reclassified as a tropical cyclone.[22] Immediately upon entering the region, increasing westerly vertical wind shear allowed dry air to become entrained in the storm's circulation. A rapid weakening trend ensued, despite the warm sea surface temperatures in the vicinity.[23] The system's deep convection proceeded to unravel, leaving the low-level circulation centre exposed, and ten-minute sustained winds decreased to 75 kilometres per hour (47 mph) by 00:00 UTC on 19 March.[22][24] As the convective structure weakened further, Savannah was downgraded to a gale-force remnant tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on 20 March. The system turned briefly east-southeastwards before adopting a track towards the west-northwest on 21 March.[22] The JTWC downgraded Savannah below tropical storm status at 12:00 UTC that day.[20] Ex-Tropical Cyclone Savannah was last mentioned by MFR on 23 March, and dissipated by 12:00 UTC the next day in the central Indian Ocean.[25][26]

Impacts

Indonesia

The Indonesian islands of Java and Bali were significantly affected by Savannah's precursor tropical low during the first half of March. Very heavy rainfall occurred across large parts of the islands as the tropical low tracked westwards, causing rapid river level rise, flooding and many landslides. A total of ten people died during the disaster, making Savannah the deadliest tropical cyclone in the Australian region since Tropical Cyclone Cempaka, which killed at least 41 people in Java in November 2017.[10][11][12][13]

The Indonesian Agency for Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics indicated that 148 mm (5.8 in) of precipitation fell in parts of Yogyakarta during 17 March. The regency of Bantul, located downstream from six major rivers, as well as the neighbouring Purworejo Regency, experienced widespread flooding with depths of up to 2 m (6.6 ft). More than 5,000 residents were forced to evacuate, and access to electricity to was cut by the floodwaters. Numerous landslides in Bantul were also triggered by the extreme rainfall, causing damage and hampering rescue and evacuation efforts. One landslide in Bantul's Imogiri district destroyed two houses at the bottom of a cliff, killing three people, and leaving one more missing. Another person was later swept away by floodwaters, and another was killed when a wall collapsed.[10][14]

The economic losses that occurred in Madiun Regency were the worst in two decades, with damages and losses amounting to more than Rp54 billion (US$3.8 million), and more than 5,700 families affected by the disaster. 5,086 houses were damaged by floodwaters throughout the region, and flooding and landslides destroyed three bridges and covered many roads, impeding transportation.[1][27] A car crash occurred on a wet road in Madiun, resulting in the death of a five-year-old boy and serious injuries to two adults.[11] 497 hectares (1230 acres) of rice fields were submerged, causing crops to fail and farmers to harvest early to prevent further damage. Significant livestock losses also occurred, including cows, goats and more than 4,000 chickens.[1] In the nearby village of Klumutan, inundation of up to 5 m (16 ft) in depth damaged hundreds of houses.[28] Two residents in a village in Madiun died of illness during the event, but were unable to be buried initially due to the flooding of the local cemetery.[29]

Further damage and agricultural losses occurred in the regencies of Ngawi, Tulungagung, Bojonegoro and Ponorogo, totalling more than Rp51 billion (US$3.6 million). In Ngawi, flooding caused approximately 1,400 hectares (3,500 acres) of agricultural land to become submerged, and damages and economic losses in that regency alone reached Rp33.2 billion (US$2.35 million).[5] 1,183 hectares (2,920 acres) of agricultural land was damaged by flooding in Tulungagung, with crops of rice, melon, chili, long bean and onion affected.[3] In Bojonegoro, flooding of the Solo River resulted in widespread impacts. Inundation occurred in 48 villages, affecting more than 1,600 families and causing 50 families to evacuate. A total of 2,097 hectares (5,180 acres) of rice fields were submerged by the river water, as well as two kindergartens and three schools.[4] Even after beginning to recede, the level of the Solo River was at above 27.44 m (90.0 ft) in Karangnongko District, causing the Indonesian National Board for Disaster Management to issue red alerts for riverine flooding for areas further downstream.[30] Flooding in Ponorogo from the Solo River caused five bridges to collapse, and submerged 1,700 hectares (4,200 acres) of rice crops.[2]

Combined damage in the regencies of Magetan, Sukoharjo, Klaten and Bulelung exceeded Rp2 billion (US$140,000). In Magetan, flooding of several rivers caused significant damage to infrastructure, agricultural land and residential areas. 100 people were stranded when nearly 500 houses were flooded in two villages, and damage to roads further inhibited access to affected areas. Losses were sustained on agricultural land, and livestock were killed by the flooding.[6] 379 hectares (940 acres) of rice fields were inundates in Sukoharjo,[8] and flooding of the Gamping River in Klaten submerged 738 hectares (1,820 acres) of rice fields.[7] In Bulelung in northern Bali, heavy rainfall caused a river that was clogged with garbage and wood to overflow, damaging roads, bridges and electricity infrastructure. A government-subsidised housing complex sustained damage from the flooding, with one house being swept away by the floodwaters.[9]

Four tourists were killed and three others were injured in Magelang Regency in central Java on 13 March. The victims had been tubing along the rapids in a river when they were overcome by flash flooding.[12] Several villages in the Pasuruan Regency were affected by flooding, with roads and residential areas becoming inundated. Water levels reaching as high as 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in Kebrukan Village.[31]

Australia

The Australian territories of Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands experienced minor impacts as Savannah passed nearby. During 11 March, Savannah's precursor tropical low passed just to the south of Christmas Island.[19] At that time, the system had ten-minute sustained winds of only about 35 kilometres per hour (22 mph). As such, no strong winds were recorded on the island. A maximum gust of 50 kilometres per hour (31 mph) was observed at 20:05 UTC on 12 March once the system had strengthened further after moving away to the west.[32] A total of 60.2 mm (2.37 in) of rainfall was recorded on Christmas Island during the seven days from 8–14 March.[33] The system made its closest approach to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands on 14 March, after intensification into a Category 1 tropical cyclone.[17] In preparation for the system's anticipated impacts on the islands, the BOM began issuing tropical cyclone advice products for residents and local authorities at 06:50 UTC on 13 March. Strong sustained winds were experienced on the islands, peaking at gale-force, and a maximum gust of 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph) was recorded at 21:35 UTC on 13 March.[34] The wind caused defoliation and vegetation damage on the islands, as well as minor damage to property, but no injuries were reported.[17] Tropical cyclone advice publications were discontinued at 06:50 UTC on 14 March as the system tracked further away from the islands.[17] Over the ten days from 9–18 March, 62.6 mm (2.46 in) of rainfall was recorded at the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Airport on West Island, the territory's capital.[35]

Aftermath

Following the significant damage caused by the weather system, the Ponorogo Regency government committed to conduct dredging operations to widen the Solo River in order to mitigate future flooding impacts. The government also indicated that they would attempt to quickly rebuild damaged bridges through a special allocation of budget resources for the disaster response. Additionally, residents were urged to refrain from disposing of rubbish in the river, as it was noted that this could exacerbate the risk and impacts of flooding.[2] Significant rubbish pollution resulting in river clogging was also observed in the Bulelung Regency in Bali, where it was regarded as a contributing factor to the flooding.[9]

The East Java government allocated Rp100 billion (US$7.1 million) in funding for local governments that declared states of emergency in their local regions due to flooding. The money was intended to cover logistics, equipment, human resources and other necessities for disaster relief and cleanup efforts.[36] Farmers who were affected by the disaster were also able to access Rp6 million (US$420) in compensation from local governments for every hectare (2.5 acres) of damaged agricultural land on their property.[2] With approximately 8,000 hectares (20,000 acres) of agricultural land submerged by floodwaters during the disaster, this would have amounted to a total of approximately Rp48 billion (US$3.4 million); however, some farmers were not able to benefit from this assistance as they did not have the necessary agricultural insurance policy provided by the government.[7]

See also

- Weather of 2019

- Tropical cyclones in 2019

- Severe Tropical Cyclone Oscar–Itseng (2004)—originated in the Australian region and took a similar track to Savannah

- Cyclone Cempaka (2017)—a weak tropical cyclone that killed at least 41 people in Java during November 2017

- Severe Tropical Cyclone Ernie (2017)—took a similar track to Savannah

- Intense Tropical Cyclone Kenanga—originated in the Australian region and tracked into the South-West Indian Ocean region

Notes

References

- Mustofa, Ali (6 March 2019). "Kerugian Akibat Banjir Madiun Capai Rp54 Miliar!". Madiunpos (in Indonesian). Kompas. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Pebrianti, Charoline (15 March 2019). "Banjir 2 Hari Rugikan Ponorogo Rp 9 Miliar" (in Indonesian). detikNews. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "Banjir timbulkan kerugian Rp5 miliar lebih di Tulungagung" (in Indonesian). Antara Aceh. 11 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "38 Desa di Bojonegoro Tergenang Banjir, Kerugian Capai Rp 4 Miliar". kumparan (in Indonesian). Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "Banjir di Ngawi, Petani Merugi hingga Rp 33 Miliar". www.jpnn.com (in Indonesian). 11 March 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "BPBD Magetan: Kerugian Akibat Banjir Hampir Rp 1 Miliar". suara.com (in Indonesian). 11 March 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Media, Solopos Digital. "32,75 Ha Sawah Puso Karena Banjir, Petani Klaten Rugi Ratusan Juta Rupiah". Solopos.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- JawaPos.com (8 March 2019). "Banjir Sukoharjo, Kerugian Capai Rp 300 Juta, Sawah Terendam 379 Ha". radarsolo.jawapos.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- JawaPos.com (11 March 2019). "Disapu Air Bah, Rumah Subsidi Seharga Rp 150 Juta Diterjang Banjir". radarbali.jawapos.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- Sucahyo, Nurhadi (18 March 2019). "Badai Tropis Savannah, Sedikitnya 5 Meninggal di DIY" (in Indonesian). VOA Indonesia. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Bagus, Rahadian (7 March 2019). "Kecelakaan Mobil di Jalan Tol Madiun-Surabaya, Bocah 5 Tahun Tewas" (in Indonesian). Tribunnews. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- Mustofa, Ali (13 March 2019). "Empat Wisatawan Tewas Terseret Banjir Bandang" (in Indonesian). Tribun Bali. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "Cyclone Cempaka leaves at least 41 dead". The Jakarta Post. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Five dead, one missing after flooding, landslides in Yogyakarta". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Weekly Tropical Climate Note". Bureau of Meteorology. 5 March 2019. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Weekly Tropical Climate Note". Bureau of Meteorology. 12 March 2019. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Severe Tropical Cyclone Savannah severe weather report". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "South East Asia Gradient Level Wind Analysis (00Z)". Bureau of Meteorology. 8 March 2019. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "BOM Best Track Data". Bureau of Meteorology. 21 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Severe Tropical Cyclone Savannah Track File". National Center for Environmental Prediction. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 22 March 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Tropical Cyclone Savannah Analysis Bulletin #1 (18Z)" (PDF). Météo-France. 17 March 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Intense Tropical Cyclone Savannah Track File". Météo-France (in French). 22 March 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Tropical Cyclone Savannah Analysis Bulletin #2 (00Z)" (PDF). Météo-France. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Tropical Cyclone Savannah Analysis Bulletin #6 (00Z)" (PDF). Météo-France. 19 March 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Tropical Cyclone Activity Bulletin" (PDF). Météo-France. 23 March 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Tropical Cyclone Activity Bulletin" (PDF). Météo-France. 24 March 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Media, Kompas Cyber (6 March 2019). "Diterjang Banjir, Ruas Jalan Nasional Madiun-Ngawi Putus Total". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Media, Kompas Cyber (6 March 2019). "Banjir Terjang 3 Kecamatan di Kabupaten Madiun, Ratusan Rumah Terendam". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Muhlis, Al Alawi (10 March 2019). "Kapolres: Kabar 2 Orang Tewas akibat Banjir di Madiun Hoaks" (in Indonesian). Solopos. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "BPBD Sebut Kerugian Banjir Bengawan Solo Capai Rp1 Miliar" (in Indonesian). CNN Indonesia. 7 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Arifin, Muhajir (21 March 2019). "Desa di Pasuruan Terendam Banjir Lebih 1 Meter, Aktivitas Warga Lumpuh" (in Indonesian). detikNews. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "Christmas Island March 2019 daily weather observations". Bureau of Meteorology. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Christmas Island rainfall data". Bureau of Meteorology. 21 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Cocos (Keeling) Islands March 2019 weather observations". Bureau of Meteorology. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Cocos (Keeling) Islands rainfall data". Bureau of Meteorology. 21 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Pemprov Jatim Anggarkan Rp100 Miliar Untuk Bencana Banjir" (in Indonesian). Medcom. 11 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

External links

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Météo-France at La Réunion (in French)

- Indonesian Agency for Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics (in Indonesian)

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center

- Official severe weather report on Severe Tropical Cyclone Savannah