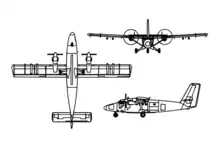

de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter

The de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter is a Canadian STOL (Short Takeoff and Landing) utility aircraft developed by de Havilland Canada in the mid-1960s and still in production today. De Havilland Canada produced it from 1965 to 1988; Viking Air purchased the type certificate, then restarted production in 2008 before re-adopting the DHC name in 2022. The aircraft's fixed tricycle undercarriage, STOL capabilities, twin turboprop engines and high rate of climb have made it a successful commuter airliner, typically seating 18–20 passengers, as well as a cargo and medical evacuation aircraft. In addition, the Twin Otter has been popular with commercial skydiving operations, and is used by the United States Army Parachute Team and the 98th Flying Training Squadron of the United States Air Force.

| DHC-6 Twin Otter | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Winair DHC-6 Twin Otter landing at St Barthélemy Gustaf III Airport. | |

| Role | Utility aircraft |

| Manufacturer | de Havilland Canada Viking Air |

| First flight | 20 May 1965 |

| Introduction | 1966 |

| Status | In production[1] |

| Produced | 1965–1988 (Series 100–300) 2008–present (Series 400) |

| Number built | December 2019: 985 (844 DHC, 141 Viking)[2] |

| Developed from | de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter |

Design and development

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Development of the aircraft began in 1964, with the first flight on 20 May 1965. A twin-engine replacement for the single-engine DHC-3 Otter retaining DHC's STOL qualities, its design features included double-slotted trailing-edge flaps and ailerons that work in unison with the flaps to boost STOL performance. The availability of the 550 shaft horsepower (410 kW) Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-20 turboprop in the early 1960s made the concept of a twin more feasible. A DHC-3 Otter with its piston engine replaced with two PT6A-4[3] engines had already flown in 1963. It had been extensively modified for STOL research.[4] To bush plane operators, the improved reliability of turboprop power and the improved performance of a twin-engine configuration made it an immediately popular alternative to the piston-powered Otter which had been flying since 1951.

The first six aircraft produced were designated Series 1, indicating that they were prototype aircraft. The initial production run consisted of Series 100 aircraft, serial numbers seven to 115 inclusive. In 1968, Series 200 production began with serial number 116. Changes made at the beginning of Series 200 production included improving the STOL performance, adding a longer nose that was equipped with a larger baggage compartment (except for aircraft fitted with floats), and fitting a larger door to the rear baggage compartment. All Series 1, 100, and 200 aircraft and their variants (110, 210) were fitted with the 550 shp (410 kW) PT6A-20 engines.

In 1969, the Series 300 was introduced, beginning with serial number 231. Both aircraft performance and payload were improved by fitting more powerful PT6A-27 engines. This was a 680 hp (510 kW) engine that was flat rated to 620 hp (460 kW) for use in the Series 300 Twin Otter. The Series 300 proved to be the most successful variant by far, with 614 Series 300 aircraft and their subvariants (Series 310 for United Kingdom operators, Series 320 for Australian operators, etc.) sold before production in Toronto by de Havilland Canada ended in 1988.

In 1972, its unit cost was US$680,000,[5] In 1976, a new -300 would have cost $700,000 ($3 million 31 years later) and is still worth more than $2.5 million in 2018 despite the -400 introduction, many years after the -300 production ceased.[6]

New production

After Series 300 production ended, the remaining tooling was purchased by Viking Air of Victoria, British Columbia, which manufactures replacement parts for all of the out-of-production de Havilland Canada aircraft. On 24 February 2006, Viking purchased the type certificates from Bombardier Aviation for all the out-of-production de Havilland Canada aircraft (DHC-1 through DHC-7).[7] The ownership of the certificates gives Viking the exclusive right to manufacture new aircraft.

On 17 July 2006, at the Farnborough Airshow, Viking Air announced its intention to offer a Series 400 Twin Otter. On 2 April 2007, Viking announced that with 27 orders and options in hand, it was restarting production of the Twin Otter, equipped with more powerful Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-34 engines.[8] As of November 2007, 40 firm orders and 10 options had been taken and a new final assembly plant was established in Calgary, Alberta.[9][10] Zimex Aviation of Switzerland received the first new production aircraft, serial number 845, in July 2010.[11][12] By mid-2014, Viking had built 55 new aircraft at its Calgary facility. The production rate as of summer 2014 was about 24 aircraft per year. In April 2015, Viking announced a reduction of the production rate to 18 aircraft per year.[13] On 17 June 2015, Viking further announced a partnership with a Chinese firm, Reignwood Aviation Group. The group will purchase 50 aircraft and become the exclusive representatives for new Series 400 Twin Otters in China.

Major changes introduced with the Series 400 include Honeywell Primus Apex fully integrated avionics, deletion of the AC electrical system, deletion of the beta backup system, modernization of the electrical and lighting systems, and use of composites for non load-bearing structures such as doors.[14]

The 100th Series 400 Twin Otter (MSN 944) was displayed at the July 2017 EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. Currently, 38% are operated as regional airliners, 31% in military aviation or special missions, 26% in industrial support and 5% in private air charter. Additionally, 70 are on regular landing gear wheels, 18 are configured as straight or amphibious floatplanes, 10 have tundra tires and 2 have wheel skis.[15]

In 2019, Viking started making plastic components for the Twin Otter by 3D printer to help reduce cost.[16] Twin Otter production was suspended in 2019 during the COVID-19 pandemic. In July 2022, DHC announced that it was reviewing the program and supply chain, with a decision on when to resume production expected "in the near future".[17] In 2023, its equipped price was $7.25M.[18]

Operational history

Twin Otters could be delivered directly from the factory with floats, skis, or tricycle landing gear fittings, making them adaptable bush planes for remote and northern areas. Areas including Canada and the United States, (specifically Alaska) had much of the demand. Many Twin Otters still serve in the Arctic and subarctic, but they can also be found in Africa, Australia, Asia, Antarctica, and other regions where bush planes are the optimum means of travel. Their versatility and manoeuvrability have made them popular in areas with difficult flying environments such as Papua New Guinea. In Norway, the Twin Otter paved the way for the network of short-field airports, connecting rural areas with larger towns. The Twin Otter showed outstanding reliability, and remained in service until 2000 on certain routes. Widerøe of Norway was, at one time, the world's largest operator of Twin Otters. During one period of its tenure in Norway, the Twin Otter fleet achieved over 96,000 cycles (take-off, flight, and landing) per year.

A number of commuter airlines in the United States got their start by operating Twin Otters in scheduled passenger operations. Houston Metro Airlines (which later changed its name to Metro Airlines) constructed their own STOLport airstrip with a passenger terminal and maintenance hangar in Clear Lake City, Texas, near the Johnson Space Center. The Clear Lake City STOLport was specifically designed for Twin Otter operations. According to the February 1976 edition of the Official Airline Guide, Houston Metro operated 22 round-trip flights every weekday at this time between Clear Lake City (CLC) and Houston Intercontinental Airport, now George Bush Intercontinental Airport, in a scheduled passenger airline shuttle operation.[19] Houston Metro had agreements in place for connecting passenger feed services with Continental Airlines and Eastern Air Lines at Houston Intercontinental, with this major airport having a dedicated STOL landing area at the time specifically for Twin Otter flight operations. The Clear Lake City STOLport is no longer in existence.

The Walt Disney World resort in Florida was also served with scheduled airline flights operated with Twin Otter aircraft. The Walt Disney World Airport, also known as the Lake Buena Vista STOLport, was a private airfield constructed by The Walt Disney Company with Twin Otter operations in mind. In the early 1970s, Shawnee Airlines operated scheduled Twin Otter flights between the Disney resort and nearby Orlando Jetport, now Orlando International Airport, as well as to Tampa International Airport. This service by Shawnee Airlines is mentioned in the "Air Commuter Section" of the 6 September 1972 Eastern Air Lines system timetable as a connecting service to and from Eastern flights.[20] This STOL airfield is no longer in use.

Another commuter airline in the United States, Rocky Mountain Airways, operated Twin Otters from the Lake County Airport in Leadville, Colorado. At an elevation of 3,026 m (9,927 ft) above mean sea level, this airport is the highest airfield in the United States ever to have received scheduled passenger airline service, thus demonstrating the wide-ranging flight capabilities of the Twin Otter. Rocky Mountain Airways went on to become the worldwide launch customer for the larger, four-engine de Havilland Canada Dash 7 STOL turboprop, but continued to operate the Twin Otter, as well.

Larger scheduled passenger airlines based in the United States, Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean and Australia, particularly jetliner operators, also flew Twin Otters, with the aircraft providing connecting feeder service for these airlines. Jet aircraft operators which also flew the Twin Otter included Aeronaves de Mexico, Air BC, Alaska Airlines, ALM Antillean Airlines, Ansett Airlines, Cayman Airways, Frontier Airlines, LIAT, Norcanair, Nordair, Ozark Air Lines, Pacific Western Airlines, Quebecair, South Pacific Island Airways, Time Air, Transair, Trans Australia Airlines (TAA), Wardair and Wien Air Alaska.[21][22] In many cases, the excellent operating economics of the Twin Otter allowed airlines large and small to provide scheduled passenger flights to communities that most likely would otherwise never have received air service.

Twin Otters are also a staple of Antarctic transportation.[23] Four Twin Otters are employed by the British Antarctic Survey on research and supply flights, and several are employed by the United States Antarctic Program via contract with Kenn Borek Air. On 24–25 April 2001, two Twin Otters performed the first winter flight to Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station to perform a medical evacuation.[24][25][26][27]

On 21–22 June 2016, Kenn Borek Air's Twin Otters performed the third winter evacuation flight to Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station to remove two people for medical reasons.[28]

The Argentine Air Force has used the Twin Otter in Antarctica[29] since the 1970s, with at least one of them deployed year-round at Marambio Base.[30] The Chilean Air Force has operated the type since 1980, usually having an example based at Presidente Frei Antarctic base of the South Shetland Islands.

As of August 2006, a total of 584 Twin Otter aircraft (all variants) remained in service worldwide. Major operators at the time included: Libyan Arab Airlines, Maldivian Air Taxi, Trans Maldivian Airways, Kenn Borek Air, and Grand Canyon Scenic Airlines. Some 115 airlines operated smaller numbers of the aircraft including Yeti Airlines in Nepal, Malaysia Airlines (which used the Twin Otter exclusively for passenger and freight transportation to the Kelabit Highlands region in Sarawak), and in the United Kingdom, the Scottish airline, Loganair which uses the aircraft to service the island of Barra in the Outer Hebrides. This daily scheduled service is unique as the aircraft lands on the beach and the schedule is partly influenced by the tide tables. Trials at Barra Airport with heavier planes than the Twin Otter, like the Short 360, failed because they sank in the sand. The Twin Otter is also used for landing at Juancho E. Yrausquin Airport, the world's shortest commercial runway, on the Caribbean island of Saba, Netherlands Antilles.

The Twin Otter has been popular with commercial skydiving operations. It can carry up to 22 skydivers to over 5,200 m (17,000 ft) (a large load compared to most other aircraft in the industry); presently, the Twin Otter is used in skydiving operations in many countries. The United States Air Force operates three Twin Otters for the United States Air Force Academy's skydiving team.

On 26 April 2001, the first ever air rescue during polar winter from the South Pole occurred with a ski-equipped Twin Otter operated by Kenn Borek Air.[31][32][33]

On 25 September 2008, the Series 400 Technology Demonstrator achieved "power on" status in advance of an official rollout.[34][35] The first flight of the Series 400 technical demonstrator, C-FDHT, took place 1 October 2008, at Victoria International Airport.[36][37]

Two days later, the aircraft departed Victoria, British Columbia for a ferry flight to Orlando, Florida, site of the 2008 National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) Conference and exhibition. The first new build Series 400 Twin Otter (SN 845) made its first flight on 16 February 2010, in Calgary, Alberta.[38] Transport Canada presented Viking Air Limited with an amended DHC-6 Type Certificate including the Series 400 on 21 July 2010.[10] Six years after, in July 2016, 100 series 400 have been delivered to 34 customers operating in 29 countries.[39]

In June 2017, 125 have been made since restarting production in 2010.[40]

Variants

- DHC-6 Series 100

- Twin-engine STOL utility transport aircraft, powered by two 550 shp (410 kW) Pratt & Whitney PT6A-20 turboprop engines.

- DHC-6 Series 110

- Variant of the Series 100 built to conform to BCAR (British Civil Air Regulations).

- DHC-6 Series 200

- Improved version.

- DHC-6 Series 300

- Twin-engine STOL utility transport aircraft, powered by two 680 shp (510 kW) (715 ESHP) Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-27 turboprop engines.

- DHC-6 Series 300M

- Multi-role military transport aircraft. Two of these were produced as "proof-of-concept" demonstrators. Both have since been reverted to Series 300 conformity.

- DHC-6 Series 310

- Variant of the Series 300 built to conform to BCAR (British Civil Air Regulations).

- DHC-6 Series 320

- Variant of the Series 300 built to conform to Australian Civil Air Regulations.

- DHC-6 Series 300S

- Six demonstrator aircraft fitted with eleven seats, wing spoilers and an anti-skid braking system. All have since been reverted to Series 300 conformity.

- Viking Air DHC-6 Series 400

- Viking Air production, first delivered in July 2010, powered by two Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-34 engines, and available on standard landing gear, straight floats, amphibious floats, skis, wheel skis, or intermediate flotation landing gear ("tundra tires").

- Viking Air DHC-6 Series 400S Seaplane

- Viking Air seventeen-seat seaplane version of the Series 400 with twin floats and corrosion-resistance measures for the airframe, engines and fuels system. Customer deliveries planned from early 2017.[41] 500 lb (230 kg) lighter than the 400.[42]

- DHC-6 Classic 300-G

- Updated DHC-6 Series 400, with an all-new interior and new flight deck featuring a glass cockpit.[43]

- CC-138

- Twin-engine STOL utility transport, search and rescue aircraft for the Canadian Armed Forces Search and Rescue operations. Based on the Series 300 aircraft.

- UV-18A

- Twin-engine STOL utility transport aircraft for the Alaska National Guard. Six built. It has been replaced by the Short C-23 Sherpa in United States Army service. In 2019 the United States Naval Research Laboratory added a UV-18A to the Scientific Development Squadron One (VXS-1) inventory.[44]

- UV-18B

- Parachute training aircraft for the United States Air Force Academy. The United States Air Force Academy's 98th Flying Training Squadron maintains three[45] UV-18s in its inventory as free-fall parachuting training aircraft,[46] and by the Academy Parachute Team, the Wings of Blue, for year-round parachuting operations. Based on the Series 300 aircraft.

- UV-18C

- United States Army designation for three Viking Air Series 400s delivered in 2013.[47]

Operators

In 2016, there were 281 Twin Otters in airline service with 26 new aircraft on order: 112 in North/South America, 106 in Asia Pacific and Middle East (16 orders), 38 in Europe (10 orders) and 25 in Africa.[48]

In 2018, a total of 270 Twin Otters were in airline service, and 14 on order: 111 in North/South America, 117 in the Asia Pacific and Middle East (14 orders), 26 in Europe and 13 in Africa.[49]

In 2020, there were a total of 315 Twin Otters worldwide with 220 in service, 95 in storage and 8 on order. By region there were 22 in Africa, 142 in Asia Pacific (8 orders), 37 in Europe, 4 in the Middle East and 110 in the Americas.[50]

The Twin Otter has been popular not only with bush operators as a replacement for the single-engine de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter but also with other civil and military customers, with over 890 aircraft built. Many commuter airlines in the United States got their start by flying the Twin Otter in scheduled passenger operations.

| Operator | Total | In service | Storage | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans Maldivian Airways | 56 | 21 | 35 | Maldives |

| Kenn Borek Air | 15 | 11 | 4 | Canada |

| Grand Canyon Airlines | 13 | 6 | 7 | United States |

| Maldivian | 11 | 10 | 1 | Maldives |

| Transwest Air | 9 | 9 | 0 | Canada |

| Zimex Aviation | 9 | 7 | 2 | Switzerland |

| AeroGeo | 8 | 0 | 8 | Russia |

| Air Borealis (PAL Airlines) | 8 | 8 | 0 | Canada |

| Air Adelphi | 7 | 6 | 1 | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

| Air Inuit | 7 | 7 | 0 | Canada |

| LADE | 7 | 5 | 2 | Argentina |

| AIRFAST Indonesia | 6 | 6 | 0 | Indonesia |

| Aviastar Mandiri | 6 | 5 | 1 | Indonesia |

| Manta Air | 6 | 5 | 1 | Maldives |

| MASwings | 6 | 2 | 4 | Malaysia |

| Merpati | 6 | 0 | 6 | Indonesia |

| Air Tuvalu | 1 | 0 | 1 | Tuvalu |

Accidents and incidents

| Date | Flight | Fat. | Location | Country | Event | Surv. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 November 1968 | Cable Commuter Airlines | 9 | Santa Ana, California | United States | While landing, impacted light pole in fog, 1.8 mi (2.9 km) short of John Wayne Airport.[52] | |

| 29 June 1972 | Air Wisconsin Flight 671 | 5 | Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin | United States | Collided mid-air with a North Central Airlines Convair 580 carrying five, killing all.[53] | |

| 5 January 1975 | Argentine Army Aviation | 13 | Tucumán Province | Argentina | Crashed due to bad weather and lack of a flight plan.[54] | |

| 9 January 1975 | Golden West Airlines Flight 261 | 12 | Whittier, California | United States | Collided with a Cessna 150, also killing its two occupants | |

| 3 May 1976 | Demonstration | 11 | Monze Air Force Base, Monze | Zambia | Crashed on take off[55] | |

| 12 December 1976 | Allegheny Commuter Flight 977 | 3 | Cape May Airport, Erma, New Jersey | United States | Crashed short of the runway | |

| 18 January 1978 | Frontier Airlines | 3 | Pueblo, Colorado | United States | Crashed during a training flight[56] | |

| 2 September 1978 | Airwest Airlines | 11 | Coal Harbour, Vancouver, British Columbia | Canada | Approach loss of control after a corroded rod failed and a flap retracted[57] | 2 |

| 18 November 1978 | Jonestown cult rescue | Port Kaituma | Guyana | Attacked by cultists while rescuing people; aircraft managed to successfully escape. Another aircraft did not leave and the occupants were shot dead[58][59] | ||

| 4 December 1978 | Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217 | 2 | Buffalo Pass, Colorado | United States | Survivable impact on snow, severe icing and mountain-wave downdraft[60] | |

| 30 May 1979 | Downeast Airlines Flight 46 | 17 | Rockland, Maine | United States | Departed from Boston, crashed 1.2 mi (1.9 km) away from Knox County Regional Airport | 1 |

| 24 July 1981 | Air Madagascar Flight 112 | 19 | Maroantsetra | Madagascar | Controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) into a mountain in cloudy conditions[61] | |

| 31 July 1981 | Panamanian Air Force FAP-205 | 7 | Coclé Province | Panama | Killed President Omar Torrijos,[62] cause disputed | |

| 21 February 1982 | Pilgrim Airlines Flight 458 | 1 | Scituate Reservoir Rhode Island | United States | Emergency landing after a fire broke out on board[63] | 10 |

| 11 March 1982 | Widerøe Flight 933 | 15 | Barents Sea near Gamvik | Norway | A mechanical fault in the elevator control system caused the pilots to lose control of pitch | |

| 18 June 1986 | Grand Canyon Airlines Flight 6 | 20 | Grand Canyon, Arizona | United States | Collided with a Helitech Bell 206, also killing its five occupants | |

| 28 October 1989 | Aloha Island Air Flight 1712 | 20 | Molokai, Hawaii | United States | Crashed into a mountain on approach to Molokai Airport.[64] | |

| 12 April 1990 | Widerøe Flight 839 | 5 | outside Værøy | Norway | Crashed in the ocean due to wind | |

| 22 April 1992 | Perris Valley Aviation | 16 | Perris Valley Airport, Perris, California | United States | Fuel contamination, lost power and crashed near the runway end[65] | 6 |

| 27 October 1993 | Widerøe Flight 744 | 6 | east of Namsos | Norway | Controlled flight into terrain into forest on a hill during approach at night in bad weather | 13 |

| 17 December 1994 | Mission Aviation Fellowship | 28 | Papua New Guinea | Crashed en route,[66] striking a mountain at 6,400 ft (2,000 m).[67] | ||

| 10 January 1995 | Merpati Nusantara Airlines Flight 6715 | 14 | Molo Strait | Indonesia | Disappeared in bad weather from Sultan Muhammad Salahudin Airport to Frans Sales Lega Airport, Ruteng.[68] | |

| 30 November 1996 | ACES Colombia Flight 148 | 15 | near Medellín | Colombia | Crashed 8 km (5.0 mi) from Olaya Herrera Airport[69] | |

| 7 January 1997 | Polynesian Airlines Flight 211 | 3 | Mount Vaea | Samoa | Controlled flight into terrain in bad weather while diverting to Faleolo International Airport from Pago Pago to Apia | 2 |

| 24 March 2001 | Air Caraïbes Flight 1501 | 19 | Saint Barthélemy | French West Indies | Crashed near Gustaf III Airport, killing one on ground.[70] | |

| 26 May 2006 | Air São Tomé and Príncipe training flight | 4 | Ana Chaves Bay, São Tomé Island | São Tomé and Príncipe | Airline's sole aircraft, registered S9-BAL, crashed during training flight.[71] | |

| 9 August 2007 | Air Moorea Flight 1121 | 20 | Mo'orea | French Polynesia | Bound for Tahiti, crashed shortly after takeoff near Moorea Airport[72] | |

| 6 May 2007 | French Air and Space Force | 9 | Sinai Peninsula | Egypt | Crashed while supporting the Multinational Force and Observers[73] | |

| 8 October 2008 | Yeti Airlines Flight 101 | 18 | Lukla | Nepal | Destroyed on landing at Tenzing-Hillary Airport[74] | 1 |

| 2 August 2009 | Merpati Nusantara Airlines Flight 9760D | 16 | near Oksibil | Indonesia | Crashed about 22 km (14 mi) north of Oksibil.[75] | |

| 11 August 2009 | Airlines PNG Flight 4684 | 13 | Kokoda Valley | Papua New Guinea | Crashed on a mountain whilst en route from Port Moresby to Kokoda.[76] | |

| 15 December 2010 | 2010 Tara Air Twin Otter crash | 22 | Bilandu Forest | Nepal | A Tara Air Twin Otter crashed after take-off on a domestic flight from Lamidanda to Kathmandu, Nepal[77] | |

| 20 January 2011 | Ecuadorian Air Force | 6 | El Capricho | Ecuador | En route from Río Amazonas Airport to Mayor Galo de la Torre Airport[78] | |

| 22 September 2011 | Arctic Sunwest Charters | 2 | Yellowknife, Northwest Territories | Canada | Float plane crashed in the street, injuring seven.[79] | |

| 23 January 2013 | Kenn Borek Air | 3 | Mount Elizabeth | Antarctica | Skiplane lost en route from the South Pole to Terra Nova Bay.[80][81][82][83] | |

| 10 October 2013 | MASwings Flight 3002 | 2 | Kudat | Malaysia | Crashed on landing at Kudat Airport[84] | 14 |

| 16 February 2014 | Nepal Airlines Flight 183 | 18 | Arghakhanchi District | Nepal | En route to Jumla from Pokhara.[85] | |

| 20 September 2014 | Hevilift | 4 | near Port Moresby | New Guinea | Crashed on landing[86] | 5 |

| 24 February 2016 | Tara Air Flight 193 | 23 | Pokhara | Nepal | Tara Air crashed after takeoff[87] | |

| 2 October 2015 | Aviastar Flight 7503 | 10 | Luwu Regency | Indonesia | Aviastar pilot deviated from his route to Makassar | |

| 30 August 2018 | Ethiopian Air Force | 18 | near Mojo | Ethiopia | From Dire Dawa, crashed at a place called Nannawa[88] | |

| 18 September 2019 | PT Carpediem Aviasi Mandiri | 4 | Papua | Indonesia | From Timika, crashed at Hoeya district[89] | |

| 29 May 2022 | Tara Air Flight 197 | 22 | Mustang District | Nepal | Crashed after takeoff from Pokhara Airport | |

| 20 May 2023 | [not listed] | 2 | Half Moon Bay, CA | United States | Crashed into Half Moon Bay, California | |

| 4 August 1986 | LIAT Flight 319 | 13 | St. Vincent and the Grenadines | St. Vincent | Crashed into the Caribbean Sea. The aircraft was en route between St. Lucia and St. Vincent when it crashed due to poor weather conditions, while on approach. | 0 |

Specifications

| Series | 100[90] | 300[90] | 400[91] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | 1–2 | ||

| Seating | 20 | 19 | |

| Length | 49 ft 6 in (15.09m) | 51 ft 9 in (15.77 m) | |

| Height | 19 ft 6 in / 5.94 m | ||

| Wing | 65 ft 0 in (19.81 m) span, 420 sq ft (39 m2) area (10.05 AR) | ||

| Empty weight | 5,850l lb / 2,653 kg | 7,415 lb / 3,363 kg | 7,100 lb / 3,221 kg (no accommodation) |

| MTOW | 10,500 lb / 4763 kg | 12,500 lb / 5,670 kg[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Payload | 975 kg (2150 lb) over 1344 km (727 nm) | 1135 kg (2500 lb) over 1297 km (700 nm) 860 kg (1900 lb) over 1705 km (920 nm)[lower-alpha 2] |

1842 kg (4061 lb) over 185 km (100 nm) 1375 kg (3031 lb) over 741 km (400 nm) |

| Fuel capacity | 378 US gal / 1466 L,[lower-alpha 2] 2,590 lb / 1,175 kg | ||

| Turboprops (×2) | P&WC PT6A-20 | PT6A-27 | PT6A-34 |

| Unit Power | 431 kW / 578shp | 460 kW / 620shp | 559 kW (750 hp) |

| Max. Cruise | 297 km/h / 160kn | 338 km/h / 182kn | 337 km/h (182 kn) (FL100) |

| Takeoff to 50 ft | 1,200 ft / 366 m | ||

| Landing from 50 ft | 1,050 ft / 320 m | ||

| Stall Speed | 65 mph | ||

| Ferry Range | 771 nmi / 1,427 km | 799 nmi / 1480 km[lower-alpha 3] | |

| Endurance | 6.94 h[lower-alpha 3] | ||

| Ceiling | 25,000 ft / 7,620 m | ||

| Climb rate | 1,600 ft/min (8.1 m/s) | ||

| FL100 fuel burn 146 kn (270 km/h) |

468.2 lb (212.4 kg)/hour 0.311 nmi/lb (1.27 km/kg) | ||

| Power/mass | 0.11 hp/lb (0.18 kW/kg) | 0.1 hp/lb (0.16 kW/kg) | 0.12 hp/lb (0.20 kW/kg) |

Table notes

- military -400: 14,000 lb / 6350 kg

- 89 US Gal / 336 L optional wingtip tank for 3,190 lb 1,447 kg of fuel

- 989 nmi / 1832 km ferry range or 8.76 h of endurance with optional wingtip tanks

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Antonov An-28

- Britten-Norman Trislander

- CASA C-212 Aviocar

- Dornier 228

- Embraer EMB 110 Bandeirante

- GAF Nomad N24

- Harbin Y-12

- IAI Arava

- Let L-410 Turbolet

- PZL M28 Skytruck

- Short SC.7 Skyvan

References

Notes

- "Viking restarts Twin Otter production". flightglobal.com. 2 April 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Mike Ody; Erik Johannesson; Ian Macintosh; Neil Aird (August 2019). "Twin Otter Archive".

- Power – The Pratt & Whitney Canada Story, Kenneth H. Sullivan and Larry Milberry, CANAV Books 1989, ISBN 0-921022-01-8, p.146

- "De havilland | 1963 | 0071 | Flight Archive".

- "Airliner price index". Flight International. 10 August 1972. p. 183.

- Aircraft Value News (26 November 2018). "Dash8-400 Values Face Some Uncertainty as Viking Takes Over".

- "Viking Acquires De Havilland Type Certificates." Archived 24 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine aiabc.com, 24 February 2006. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "Viking restarts Twin Otter production." flightglobal.com, 2 April 2007. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- Sarsfield, Kate. "Viking Twin Otter Series 400 certification approaches." Flightglobal, 3 February 2010. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "News releases." Archived 8 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Viking Air. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "Twin Otter – Zimex Aviation." Archived 1 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine zimex.ch. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- Jang, Brent (14 May 2010). "The rebirth of a Canadian icon". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- "Viking Air Slashes Twin Otter Production, Lays Off 116". Aviation International News. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- Phelps, Mark. "Updated Twin Otter Takes Off." flyingmag.com, 16 October 2008. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "100th Viking Production Series 400 Twin Otter on Display at EAA Airventure 2017" (Press release). Viking Air. 21 July 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

- Ballah, Brett (28 August 2019). "De Havilland owner believes renewed focus will increase Dash 8 market share". Western Aviation News. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Hemmerdinger, Jon (19 July 2022). "De Havilland reviewing Twin Otter and Dash 8 programmes, considering updates". Flight Global.

- "Purchase planning handbook - turboprops table". Business & Commercial Aviation. Second Quarter 2023.

- North American Official Airline Guide (OAG), February 1976 edition

- "index". Departedflights.com. 14 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- airline system timetables

- airline system timetables & OAG flight guides

- "NSF PR 01-29 — Civilian Aircraft to Evacuate South Pole Patient." nsf.gov. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "2001—Doctor Evacuated from the South Pole." Archived 15 March 2006 at archive.today www.70south.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- Williams, Jeff. "Pilot says pole flight wasn't his most challenging." usatoday.com.

- "Pilots return after historic South Pole rescue." cbc.ca/news. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "Aircraft in Antarctica: British Antarctic Survey." Archived 29 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine antarctica.ac.uk. Retrieved: 31 December 2007.

- "Calgary crew evacuates pair from South Pole in daring Antarctic rescue". CBC News. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "Official picture." Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine fuerzaaerea.mil. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- Hulcazuk, Sergio. "Twin Otter: El castor patagonico." Archived 13 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine aeroespacio.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- Bob Antol (April 2001). "The Rescue of Dr. Ron Shemenski from the South Pole". Bob Antol's Polar Journals. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "Doctor rescued from Antarctica safely in Chile". New Zealand Herald. 27 April 2001. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- Transcript (26 April 2001). "Plane With Dr. Shemenski Arrives in Chile". CNN. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "Viking Twin Otter Series 400 Achieves Power On." Archived 11 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine vikingair.com, 25 September 2008. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "Twin Otter Shakes Its Wings Over Victoria Skies." Archived 11 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine canada.com, 2 October 2008. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- Padfield, R. Randall and Matt Thurber. "Revived Twin Otter Makes First Flight." Archived 11 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine ainonline.com, 8 October 2008. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "First Flight For New Twin Otter A "Boring" Success." Archived 2 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine canada.com, 1 October 2008. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "Twin Otter Series 400 completes maiden sortie." flightglobal.com, 17 February 2010. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- "Viking Readies 100th Production Series 400 Twin Otter for Delivery" (Press release). Viking Air. 12 July 2016.

- Jon Hemmerdinger (21 June 2017). "Viking targets China, Russia with Twin Otter". Flightglobal.

- "New Twin Otter Seaplane launched". Pilot. Archant Specialist. April 2016. p. 8.

- "A Visit with Viking". Air Insight. 1 November 2016.

- "De Havilland Canada launches the DHC-6 Twin Otter Classic 300-G". De Havilland Aircraft of Canada. 19 June 2023.

- Richard Scott (3 June 2019). "NRL introduces UV-18 Twin Otter aircraft into test fleet". Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "94 FTS Fact Sheet." Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine afhra.af.mil. Retrieved: 12 August 2009.

- "UV-18." globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 12 August 2009.

- Kris Osborn (1 October 2012). "Army developing new fixed-wing aircraft". army.mil. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "World Airliner Census". Flight Global. 8 August 2016. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016.

- "World Airline Census 2018". Flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "World Airliner Census 2020" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- "406 occurrences in the ASN safety database". Flight Safety Foundation. 30 August 2018.

- Accident description for de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 200 N7666 Santa Ana-Orange County Airport, CA (SNA) at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 30 May 2022.

- "National Transportation Safety Board "Aircraft Accident Report North Central Airlines, Inc., Allison Convair 340/440 (CV-580), N90858, and Air Wisconsin, Inc., DHC-6, N4043B, Near Appleton, Wisconsin, June 29, 1972, adopted April 25, 1973" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board Report Number NTSB-AAR-73-09. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "A 36 años de un fatal accidente en los cerros tucumanos" (in Spanish). 4 April 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Accident description for ASN Aircraft accident de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 C-GDHA Monze at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 16 February 2023.

- "Pilots, Dispatchers and Flight Operations". Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- Accident description for de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 200 C-FAIV Vancouver-Coal Harbour SPB, BC (CXH) at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 30 August 2018.

- "Escape from Jonestown". 12 November 2014.

- "Surviving the Heart of Darkness / Twenty years later, Jackie Speier remembers how her companions and rum helped her endure the night of the Jonestown massacre". 13 November 1998.

- Katz, Peter (7 January 2019). "After the Accident: Twin Otter Crash In The Rockies From 40 Years Ago". Plane & Pilot Magazine.

- Accident description for de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 5R-MGB Maroantsetra Airport (WMN) at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 6 July 2019.

- "24 years after the accident". Prensa.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2005.

- "National Transportation Safety Board Aircraft Accident Report NTSB-AAR-82-7" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 20 July 1982. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "National Transportation Safety Board Aircraft Accident Report NTSB/AAR-90/05" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 25 September 1990. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "National Transportation Safety Board Aviation Accident Final Report Accident Number: LAX92MA183". National Transportation Safety Board. 5 August 1993. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "Airplane Crash Kills 28 In Papua New Guinea". World News Briefs. New York Times. 19 December 1994. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012.

- Accident description for de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 200 P2-MFS Olsobip at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 16 February 2023.

- Accident description for de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 PK-NUK Molo Strait at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 27 June 2011.

- "Informe de accidente De Havilland DHC 300 – ACES HK2602" (PDF). Aeronautica civil de Colombia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2014. (in Spanish)

- "Accident survenu le 24 mars 2001 sur l'île de Saint-Barthélemy (971) au DHC-6-300 « Twin-Otter » immatriculé F-OGES exploité par Caraïbes Air Transpor" (PDF) (in French). Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile). 7 October 2001.

- "Jornal de São Tomé". 2 September 2006. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- Clark, Amy S. (9 August 2007). "20 Thought Dead In Pacific Plane Crash". CBS News. Archived from the original on 12 November 2010.

- Accident description for L'Armée de L'Air 742/CB at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 15 December 2009.

- "Tourists die in Nepal air crash". BBC News. 8 October 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- Hradecky, Simon (16 October 2009). "Crash: Merpati DHC6 enroute on Aug 2nd 2009, aircraft impacted mountain". Aviation Herald. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Mixed weather reported before PNG plane crashed". The Australian. 2 August 2009. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Shrestha, Manesh (15 December 2010). "22 dead in Nepal plane crash". CNN. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Accident description for de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 FAE449 El Capricho area at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 30 August 2018.

- "Yellowknife plane crash kills 2 people". CBC. 22 September 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- CTV News (23 January 2013). "Kenn Borek plane carrying three Canadians missing in Antarctica". CTV. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- Accident description for de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 C-GKBC Mount Elizabeth at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 25 January 2013.

- Radio-Canada (23 January 2013). "Un avion transportant trois Canadiens est disparu en Antarctique" (in French). Station Radio-Canada. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- CTV News (26 January 2013). "Wreckage of missing plane found, crash deemed 'not survivable'". CTV News. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- Accident description for de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 310 9M-MDM Kudat Airport (KUD) at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 16 February 2023.

- "Crash: Nepal DHC6 near Khidim on Feb 16th 2014, aircraft impacted terrain". Avherald.com. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- "Accident: Hevilift DHC6 near Port Moresby on Sep 20th 2014, impact with terrain". Avherald.com. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Sugam Pokharel; Holly Yan; Greg Botelho (24 February 2016). "Nepal plane crash: Tara Air plane goes down, 23 feared dead". CNN.

- Sisay, Andualem (30 August 2018). "17 killed in Ethiopia military plane crash". The EastAfrican. Nairobi. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Aditra, Irsul (25 September 2019). "Jenazah Korban Pesawat Twin Otter yang Jatuh di Papua Berhasil Dievakuasi". Kompas. Timika. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- Gerard Frawley. "De Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter". The International Directory of Civil Aircraft – via Airliners.net.

- "Twin Otter Series 400" (PDF). Viking Aircraft. 7 July 2015.

Bibliography

- Harding, Stephen (November–December 1999). "Canadian Connection: US Army Aviation's Penchant for Canadian Types". Air Enthusiast (84): 72–74. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Hotson, Fred W. The de Havilland Canada Story. Toronto: CANAV Books, 1983. ISBN 0-07-549483-3.

- Rossiter, Sean. Otter & Twin Otter: The Universal Airplanes. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1998. ISBN 1-55054-637-6.