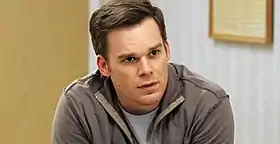

David Fisher (Six Feet Under)

David James Fisher is a fictional character played by Michael C. Hall on the HBO television series Six Feet Under. The character is the middle child of three and is a third-generation funeral director. Initially, the character is portrayed as conservative, dutiful to his family, emotionally repressed, and conflicted about his homosexuality. Over the course of the series, he faces struggles and triumphs both personally and professionally. His most significant challenges are related to keeping his funeral home in business, navigating his relationship with Keith Charles, surviving being carjacked, and coping with the death of his father. By the show's end, he reconciles his religious beliefs, personal goals, and homosexuality, and he and Keith settle down. They adopt two children: eight-year-old Anthony and 12-year-old Durrell. The series finale and official HBO website indicate that Keith is murdered in a robbery in 2029, and that David at some point finds companionship with Raoul Martinez, with whom he remains until David's death at the age of 75.

| David Fisher | |

|---|---|

| Six Feet Under character | |

| |

| Portrayed by | Michael C. Hall |

| In-universe information | |

| Occupation | Funeral director |

| Birth name | David James Fisher |

| Born | January 20, 1969 |

| Died | 2044 (aged 75) |

| Place of origin | Los Angeles, California |

Critics have cited David Fisher as the first realistic portrayal of a gay lead male character on television, and the character is popularly regarded as one of the most beloved of the series. Michael C. Hall was widely praised for his portrayal of the character, and was nominated for and won major awards as a result.[1]

Character conception

There was this stuffed-shirt quality and this vulnerable-little-boy quality at the same time. It wasn't exactly the David I'd envisioned, but it made any other idea about David irrelevant.[2]

—Alan Ball (2003)

The show's creator, Alan Ball, says he based the characters Nate, Claire, and David on himself. About David, he said: "I'm like David in that for years I tried to do everything right, as if that would some way redeem me."[3] Ball said in one interview, when he first conceived the characters: "David was just always gay. He was the brother who was 'the best little boy in the world' who did everything to please everybody, and that's such a classic gay thing."[4]

Jeremy Sisto (who was cast as Billy Chenowith) and Peter Krause (who was cast as Nate Fisher) both originally auditioned for the role of David.[5] However, director Sam Mendes had just finished working with Hall on the Broadway show Cabaret and called him one day at noon to invite him to audition for the role that evening.[6] Ball (who had worked with Mendes on the film American Beauty) said that, after four days of auditions "[Hall] started reading, and I just saw the character come to life. And it was David."[6]

Character progression

Show's outset

For the first season, he was a closeted homosexual middle-son mortician, yet he's the most traditional and conservative-minded of all the Fisher children. He's such a stew of contradiction and conflict.[7]

—Michael C. Hall (2002)

David is the second son (four years younger than Nate and 14 years older than Claire) of Nathaniel Sr. and Ruth Fisher's. The family owns and operates Fisher & Sons Funeral Home which Nathaniel, Sr. inherited from his own father. Some years prior to the pilot episode, David abandoned his desire to become a lawyer and instead, went to mortuary school to assist his father with the business. These decisions cause him to resent his older brother, who left home at 17 and only visits for major holidays. David's relationship with his mother is affectionate, but his relationship with his father is conflicted.[8] His father's death in the show's pilot episode brings their unresolved issues to the fore.

David is in many ways conservative (more so than either of his siblings) and he was even a Young Republican in college. Although he began to suspect he was gay in childhood, Season 3 reveals that he spent "ten years" dating women,[9] going as far as getting engaged to a woman named Jennifer Mason.[10] Their relationship ended when David revealed he was gay, but he remained closeted about his homosexuality. In the pilot, he is in a several-month-long relationship with Keith Charles, a police officer he met at a gay-friendly church.[11]

Season 1

I wouldn't categorize myself as being religious in a denominational sense, but I am a spiritual person. I like to think about these things, and it's curious to me all that's going on in the politics of religion in regard to gays and lesbians.[1]

—Alan Ball (2001)

Soon after his father's death, David becomes angered at Nate's sudden and permanent return home.[8] Worse, their father bequeaths half of the business to Nate,[7] which David takes as a trivialization of the sacrifices he has made for the family business.[10] His anger is complicated when a major funeral home chain called Kroehner Service International, harasses the brothers to sell to them.[8] Nate initially wants to sell and then changes his mind; Ruth backs Nate both times and as a result, David feels even further marginalized.[10]

Meanwhile, he relies emotionally on his boyfriend Keith in private, while he publicly declares them to be racquetball partners.[8] Claire observes them at her father's funeral and deduces that they are a couple.[8] Weeks later, when Nate chances upon the couple having lunch, David tacitly outs himself by taking Keith's hand, which the couple considers a personal triumph. However, moments later David chastises Keith after he angrily confronts a man who called them "fags".[12] Keith accuses David of self-loathing and dumps him.[13][7] David is devastated. In the wake of their break-up, David is offered and accepts his father's deacon position at the Episcopalian Church while secretly engaging in a series of one-night stands and risky sex.[a] He is even arrested for having sex with a prostitute, and is helped out by Keith who uses his position in the LAPD to get the charges dropped.[14] The brutal murder of a young gay man spurs him to clean his life up and come out of the closet.[1] His mother accepts him, but he is asked to resign as deacon, while the Fisher family in turn leave the church in solidarity with David.

Season 2

By the time David comes out, however, Keith is in a relationship with an emergency medical technician named Eddie. However, after Keith kills someone while on duty, he seeks David for comfort and they have sex, but to David's disappointment, Keith considers it a mistake.[15] David begins dating a lawyer named Ben, but cannot shake his love for Keith.[16] When David's and Keith's respective relationships fail, they get back together.[17] Over time, David moves into Keith's apartment. David bonds with Keith's young niece Taylor of whom Keith gets custody after Taylor's mother is incarcerated.[18] The two begin adoption proceedings. The growing pressures on Keith exacerbate his anger management problems, and he becomes increasingly distant and verbally abusive. After getting suspended from work for use of excessive force,[19] Keith sends Taylor to live with his parents without consulting David. David tolerates his behavior until an argument about attending Claire's graduation turns violent and erupts into the two men grappling on the floor before engaging in rough sex that leaves both of them slightly injured.[20]

Season 3

David and Keith decide to start therapy together to help resolve some of their communication issues.[21] When the therapist suggests that David have an independent hobby, David joins the Gay Men's Chorus of Los Angeles.[21][b] The difference between his and Keith's social circles is highlighted when Keith reluctantly plays a game of leading ladies with David's friends at a brunch,[22] and later when Keith invites David to play combat-style paintball with Keith's gay cop friends.[23] When one of the paintball players (named Sarge) is too inebriated to drive home, he stays over, which leads to the men having a three-way sexual experience.[23] A part of David enjoys "being wild," but he feels conflicted about having an open relationship; still, he hesitantly agrees to more such encounters.[24]

When David and Keith travel to San Diego for Keith's aunt's funeral, David defends Keith during an explosive and violent argument between Keith and his father, but Keith rejects his support and David, furious and humiliated, catches the bus back to Los Angeles.[25] His chorus buddy, Patrick, picks him up, and the two have sex.[25] The incident coincides with the disappearance of Nate's wife, Lisa, and David stays with his brother for a time while avoiding Keith. Soon after he returns home, a fight about a telemarketer escalates into another battle about the San Diego incident, so David breaks up with Keith and moves back to the family home.[26] A few weeks later they encounter each other at their church and have a long talk.[27]

Season 4

In the season premiere, after a hard night, Nate tells his family that a body that washed ashore has been identified as Lisa's.[28] After mediating a contentious discussion between Nate and Lisa's family, David handles the bulk of the funeral arrangements.[28] David then assists Nate in deceiving Lisa's family by giving them the unclaimed cremains from storage at the mortuary, while Nate buries Lisa's body in an open field according to her wishes.[28] After the funeral, David and Keith revisit their relationship and decide to "start over," but without therapy and on the condition that Keith quit his job.[28] However, Keith and David's relationship remains open and David receives oral sex from a plumber.[29] Keith finds employment with a private security agency to celebrities, but does not come out at work.[30] Soon, he is assigned to go on a three-month tour with a pop star named Celeste.[31]

While Keith is away, David is kidnapped at gunpoint by a hitchhiker he picks up en route to delivering a dead body to the funeral home.[31] The carjacker robs David, makes him smoke crack cocaine, beats him, and finally douses him in gasoline and puts a gun in his mouth, forcing him to beg for his life.[31] When he finds out what happened, Keith rushes home, but David convinces him to go back on tour.[32] However, David begins to experience crippling panic attacks,[32] which worry Keith from afar. David grows increasingly lonely and emotionally unhinged, starts drinking more and tearfully tells Keith that he wants them to become sexually exclusive.[33] Even so, David sleeps with the paintballer Sarge again.[33] Although Keith eventually "comes out" at work, Celeste seduces him into sleeping with her, and then fires him for the indiscretion.[33] When he comes home, Keith confesses his infidelity, and David begins to worry that Keith will leave him for a woman.[34] David eventually confesses his own tryst with Sarge.[34] The pressure builds until finally, an irrational David assaults a man at a restaurant. The victim implies that he will drop a $500,000 lawsuit if Keith will allow him to perform oral sex on him, and Keith complies.[35] The man then hires Keith for personal security.

David confronts his carjacker in jail to put the trauma behind him.[36]

Season 5

David begins to refer to Keith as his husband. As their lives begin to settle down again, they start making plans in earnest to become parents.[37][38] After a surrogacy attempt fails, the couple adopts two brothers (Durrell and Anthony) after David bonds with Anthony at an adoption fair. The boys suffer from trust issues, and Durrell is particularly rebellious due to their previous experiences in foster care.[39] When Keith considers returning them to the agency, David insists that they keep them.[39] Soon after the adoption is finalized, Nate dies and David begins to fall apart.[40] His panic attacks return along with visions of his carjacker. After six weeks, he's scarcely better and still unready to confer with his business partner (Rico) and Nate's second wife (Brenda) on how to proceed with the business, which the three co-own.[41] After David almost burns down the apartment accidentally, Keith suggests that David live elsewhere until he recovers.[41] After a brief stay with his mother, he and Keith pool their savings to purchase the shares of Fisher & Diaz owned by Brenda and Rico.[42] They redecorate and move into the Fisher home as the new owners, and re-adopt the business' former name, Fisher & Sons.[42]

David's future and death

Between the series finale, "Everyone's Waiting", and the obituaries published at the official HBO website,[42][43] the viewers learn of David's life after the show up until his death. David teaches Durrell how to embalm a body, and Durrell is seen continuing the business up to adulthood.[42] In 2009, David and Keith are legally married,[43] which was the first depicted on a fictional American series; they remain together until Keith is murdered in 2029.[42][43] At Claire's wedding, Durrell is seated with a woman and (presumably) their child, while Anthony is seated next to a man, whose hand he is holding.[42][c] David retires from Fisher & Sons in 2034 (Durrell continues the business),[43] and goes on to star in many local community theater productions.[43] He later enters a relationship with a man named Raoul Martinez, and they are together when David dies at a family function in 2044 at age 75.[43] His final vision is of a young and healthy Keith catching a football and smiling at him.[42]

Legacy

.png.webp)

David Fisher is often referred to as the first realistic gay lead portrayed on television, and the character has been widely praised for the way he was written as well as his portrayal by Michael C. Hall. The Essential HBO Reader noted how Six Feet Under offered "an affirming but alternative version of image of non-traditional families and couples," and concluded that, unlike their heterosexual counterparts on the show (Nate and Brenda), they emerge "as the ideal couple at the end."[44] Sally Munt, in her book Queer Attachments: The Cultural Politics of Shame, said, "For the first time in mass broadcasting, gay David is the 'everyman' whose quest for love and self-acceptance inculcates the viewer."[45] In reference to the scene when David comes out to his mother, Queer TV: Theories, Histories, Politics commented that it "purposefully counters the predictability of most coming out scenes in film and television texts, in which a bold declaration is followed swiftly by angry rejection or emotional acceptance."[46] The book Fade to Black and White: Interracial Images in Popular Culture called the relationships between Keith, David, their niece Taylor and their adopted children a "rare exception" to the interracial relationships on television that advance negative stereotypes.[47] Ellen Lewin, in her book Gay Fatherhood: Narratives of Family and Citizenship in America, cited David and Keith as "realistic, if somewhat parodic" examples of real gay fathers who adopt children that heterosexual couples – with "more attractive options (presumably)" – might not adopt, a trend that contrasts with the typical stereotype of the pleasure-seeking and self-indulgent gay male.[48]

David also was a reference point for cultural studies on trends in gay perception and entertainment of the time. One Temple University publication purported that "Six Feet Under offers a critique of bourgeois selfhood through the gay heroic figure of David Fisher and his psychic states are represented as a logical outcome of his homosexual middle-class identity."[49]

For his part, Hall was nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series and for an AFI Award for Actor of the Year in 2002 for his role as David Fisher. In addition, he shared in the Screen Actors Guild nominations for Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Drama Series all five years that the show was in production, winning the award in 2003 and 2004.[50]

Notes

^ a: Alan Ball said he chose the Episcopalian Church as the Fishers' place of worship because it was, in his view, an "ostensibly 'gay-friendly church,' yet one that remain[ed] deeply divided over just how welcoming it should be toward homosexuals."[1]

^ b: The show's writers drew on the talent of Michael C. Hall based on his previous stage experience. Several real members of the chorus appeared on the show.[51]

^ c: Keith's obituary states that he has one grandchild. David's obituary states that he has three grandchildren, one of whom is named Keith.[42]

Further reading

- Six Feet Under: Better Living Through Death, Edited by Alan Ball and Alan Poul, Published by Melcher Media/Pocket Books

References

- Barnhart, Aaron (July 30, 2001). "Why you should dig HBO's 'Six Feet Under'". Electronic Media. Vol. 20, no. 31. p. 9.

- Snierson, David; Fretts, Bruce; Carvell, Tim; Cannon, Bob; Feitelberg, Amy (March 14, 2003). "BEYOND THE GRAVE". Entertainment Weekly. Vol. 700, no. 16.

- Peyser, Marc; Gordon, Devin; Scelfo, Julie (March 18, 2002), "SIX FEET UNDER OUR SKIN". Newsweek. 139 (11):52

- Podeswa, Jeremy (June 21, 2005), "Six Feet over". Advocate. (941):154–157

- Levin, Gary, (March 01, 2002) "'Six Feet Under' and over the top". USA Today

- Stockwell, Anne (June 8, 2004), "Hall of Love and death". Advocate. (916):36–45

- Levin, Gary (March 01, 2002), "Step into the parlor of 'Six Feet Under'". USA Today

- "Pilot". Six Feet Under. 3 June 2001. No. 1, season 1

- "Making Love Work". Six Feet Under. 6 April 2003. No. 6, season 3

- "The Will". Six Feet Under. 10 June 2001. No. 2, season 1

- Tucker, Ken, (June 01, 2001) "Sunday Best?". Entertainment Weekly. (598):70

- "Familia". Six Feet Under. 24 June 2001. No. 4, Season 1

- "An Open Book". Six Feet Under. 1 July 2001. No. 5, season 1

- "The Trip". Six Feet Under. 12 August 2001. No. 11, season 1

- "The Invisible Woman". 31 March 2002 No. 5, season 2

- "In Place of Anger". Six Feet Under. 7 April 2002. No. 6, season 2

- "Back to the Garden". Six Feet Under. 14 April 2002. No. 7, season 2

- "The Secret:. Six Feet Under. 5 May 2002. No. 10, season 2

- "I'll Take You". Six Feet Under. 19 May 2002. No. 12, season 2

- "The Last Time". Six Feet Under. 2 June 2002. No. 13, season 2

- "Perfect Circles". Six Feet Under. 2 March 2003. No. 1, season 3

- "Timing & Space". Six Feet Under. 13 April 2003. No. 7, season 3

- "Tears, Bones & Desire". Six Feet Under. 20 April 2003. No. 8, season 3

- "The Opening". Six Feet Under. 27 April 2003. No. 9, season 3

- "Everyone Leaves". Six Feet Under. 4 May 2003. No. 10, season 3

- "Twilight". Six Feet Under. 18 May 2003. No. 12, season 3

- "I'm Sorry, I'm Lost." Six Feet Under. 1 June 2003. No. 13, season 3

- "Falling into Place". Six Feet Under. 13 June 2004. No. 1, season 4

- "In Case of Rapture." Six Feet Under. 20 June 2004. No. 2, season 4

- "Can I Come Up Now?" Six Feet Under. 11 July 2004. No. 4, season 4

- "That's My Dog." Six Feet Under. 18 July 2004. No. 5, season 4

- "Terror Starts at Home." Six Feet Under. 25 July 2004. No. 6, season 4

- "Coming and Going." Six Feet Under. 8 August 2004. No. 8, season 4

- "Grinding the Corn." Six Feet Under. 15 August 2004. No. 9, season 4

- "Bomb Shelter." Six Feet Under. 29 August 2004. No. 11, season 4

- "Untitled." 12 Six Feet Under. September 2004. No. 12, season 4

- "The Black Forest". Six Feet Under. 22 August 2004. No. 10, season 4

- "A Coat of White Primer". Six Feet Under. 6 June 2005. No. 1, season 5

- "The Rainbow of Her Reasons". Six Feet Under. 10 July 2005. No. 6, season 5

- "All Alone". Six Feet Under. 7 August 2005. No. 10, season 5

- "Static". Six Feet Under. 14 August 2005No. 11, season 5

- "Everyone's Waiting". Six Feet Under. 21 August 2005. No. 12, season 5

- "Obituary". HBO.com. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- Gary Richard Edgerton, Jeffrey P. Jones (2008) The Essential HBO Reader. University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 0-8131-2452-2, ISBN 978-0-8131-2452-0

- Queer attachments: the cultural politics of shame Queer interventions Sally Munt Publisher Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008 ISBN 0-7546-4921-0, ISBN 978-0-7546-4921-2 page 165

- Queer TV: theories, histories, politics Dr. Glyn Davis, Gary Needham. Taylor & Francis, 2009 ISBN 0-415-45046-2, ISBN 978-0-415-45046-1 page 183

- Fade to Black and White: Interracial Images in Popular Culture Erica Chito Childs ISBN 0-7425-6080-5, ISBN 978-0-7425-6080-2 Rowman & Littlefield, 2009 Page 41

- Ellen Lewin Gay Fatherhood: Narratives of Family and Citizenship in America Publisher University of Chicago Press, 2009 ISBN 0-226-47658-8, ISBN 978-0-226-47658-2 page 25

- Communication abstracts, Volume 30, Issue 3 page Temple University. School of Communications and Theater, OCLC FirstSearch Electronic Collections Online Publisher Sage Publications, 2007 University of Michigan Digitized Apr 25, 2008

- The Hollywood Reporter, Volume 401 Publisher Hollywood Reporter Inc., 2007

- Hernandez, Ernio (11 July 2003), "Gay Men's Chorus of Los Angeles Celebrate Elton John in Rocket Man, July 11–13 Archived 2012-10-16 at the Wayback Machine". Playbill.com. Retrieved on June 24, 2010