Crescent

A crescent shape (/ˈkrɛsənt/, UK also /ˈkrɛzənt/)[1] is a symbol or emblem used to represent the lunar phase in the first quarter (the "sickle moon"), or by extension a symbol representing the Moon itself.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

In Hinduism, Shiva is often shown wearing a crescent moon on his head symbolising that he is the master of time and is himself timeless.

It is used as the astrological symbol for the Moon, and hence as the alchemical symbol for silver. It was also the emblem of Diana/Artemis, and hence represented virginity. In veneration of Mary in the Catholic Church, it is associated with Mary, mother of Jesus.

From its use as roof finial in Ottoman mosques, it has also become associated with Islam, and the crescent was introduced as chaplain badge for Muslim United States military chaplains in 1993.[2]

Symbolism

The crescent symbol is primarily used to represent the Moon, not necessarily in a particular lunar phase. When used to represent a waxing or waning lunar phase, "crescent" or "increscent" refers to the waxing first quarter, while the symbol representing the waning final quarter is called "decrescent".

The crescent symbol was long used as a symbol of the Moon in astrology, and by extension of Silver (as the corresponding metal) in alchemy.[3] The astrological use of the symbol is attested in early Greek papyri containing horoscopes.[4] In the 2nd-century Bianchini's planisphere, the personification of the Moon is shown with a crescent attached to her headdress.[5]

Its ancient association with Ishtar/Astarte and Diana is preserved in the Moon (as symbolised by a crescent) representing the female principle (as juxtaposed with the Sun representing the male principle), and (Artemis-Diana being a virgin goddess) especially virginity and female chastity. In Christian symbolism, the crescent entered Marian iconography, by the association of Mary with the Woman of the Apocalypse (described with "the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars" in Revelation) The most well known representation of Mary as the Woman of the Apocalypse is the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Shape

|

|

|

|

|

|

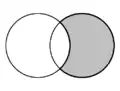

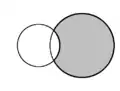

| Examples of lunes in planar geometry (shaded areas). Examples in the top row can be considered crescent shapes, because the lune does not contain the center of the original (right-most) circular disk. | ||

The crescent shape is a type of lune, the latter consisting of a circular disk with a portion of another disk removed from it, so that what remains is a shape enclosed by two circular arcs which intersect at two points. In a crescent, the enclosed shape does not include the center of the original disk.

The tapered regions towards the points of intersection of the two arcs are known as the "horns" of the crescent. The classical crescent shape has its horns pointing upward (and is often worn as horns when worn as a crown or diadem, e.g. in depictions of the lunar goddess, or in the headdress of Persian kings, etc.[6]

The word crescent is derived etymologically from the present participle of the Latin verb crescere "to grow", technically denoting the waxing moon (luna crescens). As seen from the northern hemisphere, the waxing Moon tends to appear with its horns pointing towards the left, and conversely the waning Moon with its horns pointing towards the right; the English word crescent may however refer to the shape regardless of its orientation, except for the technical language of blazoning used in heraldry, where the word "increscent" refers to a crescent shape with its horns to the left, and "decrescent" refers to one with its horns to the right, while the word "crescent" on its own denotes a crescent shape with horns pointing upward.[7]

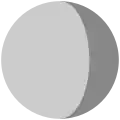

The shape of the lit side of a spherical body (most notably the Moon) that appears to be less than half illuminated by the Sun as seen by the viewer appears in a different shape from what is generally termed a crescent in planar geometry: Assuming the terminator lies on a great circle, the crescent Moon will actually appear as the figure bounded by a half-ellipse and a half-circle, with the major axis of the ellipse coinciding with a diameter of the semicircle.

Unicode encodes a crescent (increscent) at U+263D (☽) and a decrescent at U+263E (☾). The Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs block provides variants with faces: U+1F31B 🌛 FIRST QUARTER MOON WITH FACE and U+1F31C 🌜 LAST QUARTER MOON WITH FACE.

History

Early history

The crescent shape is used to represent the Moon, and the Moon deity Nanna/Sin from an early time, visible in Akkadian cylinder seals as early as 2300 BC.

The Egyptian logograph representing the Moon also had a crescent shape

(Gardiner N11, ı͗ꜥḥ "moon" (with increscent and decrescent variants); variant N12

). In addition, there is a 19th-dynasty hieroglyph representing the "moon with its lower half obscured (N9

psḏ, with a variant with a crescent shape N10

).[8]

The crescent was well used in the iconography of the ancient Near East and was used by the Phoenicians in the 8th century BC as far as Carthage and Numidia in modern Tunisia and Algeria. The crescent and star also appears on pre-Islamic coins of South Arabia.[9]

The combination of star and crescent also arises in the ancient Near East, representing the Moon and Ishtar (the planet Venus), often combined into a triad with the solar disk.[10] It was inherited both in Sassanian and Hellenistic iconography.

Classical antiquity

Selene, the moon goddess, was depicted with a crescent upon her head, often referred to as her horns, and a major identifying feature of hers in ancient works of art.[11][12]

In the iconography of the Hellenistic period, the crescent became the symbol of Artemis-Diana, the virgin hunter goddess associated with the Moon. Numerous depictions show Artemis-Diana wearing the crescent Moon as part of her headdress. The related symbol of the star and crescent was the emblem of the Mithradates dynasty in the Kingdom of Pontus and was also used as the emblem of Byzantium.

Bust of Selene on a Roman sarcophagus (3rd century)

Bust of Selene on a Roman sarcophagus (3rd century)

Middle Ages

The crescent remained in use as an emblem in the Sasanian Empire, used as a Zoroastrian regal or astrological symbol. In the Crusades it came to be associated with the Orient (the Byzantine Empire, the Levant and Outremer in general) and was widely used (often alongside a star) in Crusader seals and coins. It was used as a heraldic charge by the later 13th century. Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus, the claimant to the Byzantine Empire who ruled Cyprus until overthrown by the crusading King Richard I of England, used arms with "a crescent of gold on a shade of azure, with a blazing star of eight points". Later, King Richard granted the same as the coat of arms of the city of Portsmouth, in recognition of the significant involvement of soldiers, sailors, and vessels from Portsmouth in the conquest of Cyprus.[13] This remains Portsmouth's coat of arms up to the present.

Anna Notaras, daughter of the last megas doux of the Byzantine Empire Loukas Notaras, after the fall of Constantinople and her emigration to Italy, made a seal with her coat of arms which included "two lions holding above the crescent a cross or a sword".[14]

From its use in the Sasanian Empire, the crescent also found its way into Islamic iconography after the Muslim conquest of Persia. Umar is said to have hung two crescent-shaped ornaments captured from the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon in the Kaaba.[15] The crescent appears to have been adopted as an emblem on military flags by the Islamic armies from at least the 13th century, although the scholarly consensus holds that the widespread use of the crescent in Islam develops later, during the 14th to 15th century.[16] The use of such flags is reflected in the 14th-century Libro del Conoscimiento and the Catalan Atlas. Examples include the flags attributed to Gabes, Tlemcen, Tunis and Buda,[17] Nubia/Dongola (documented by Angelino Dulcert in 1339) and the Mamluks of Egypt.[18]

The Roman Catholic fashion of depicting Madonna standing or sitting on a crescent develops in the 15th century.

Early modern and modern

The goddess Diana was associated with the Moon in classical mythology. In reference to this, feminine jewelry representing crescents, especially diadems, became popular in the early modern period. The tarot card of the "Popess" also wears a crescent on her head.

Conrad Grünenberg in his Pilgrimage to the Holy Land (1486) consistently depicts cities in the Holy Land with crescent finials.[19] Flags with crescents appear to have been used on Ottoman vessels since at least the 16th century.

Prints depicting the Battle of Lepanto (1571), including the print by Agostino Barberigo of Rome made just a few weeks after the battle,[20] and the Martino Rota of Venice in the following year, show the Ottoman vessels displaying flags with one or several crescents in various orientations (as do the monumental paintings commissioned later based on these prints). Rota also shows numerous crescent finials, both on ships and on fortresses depicted in the background, as well as some finials with stars or suns radiant, and in some cases a sun radiant combined with a crescent in the star-and-crescent configuration.

The official adoption of star and crescent as the Ottoman state symbol started during the reign of Sultan Mustafa III (1757–1774) and its use became well-established during Sultan Abdul Hamid I (1774–1789) and Sultan Selim III (1789–1807) periods. A buyruldu (decree) from 1793 states that the ships in the Ottoman navy have that flag.[21]

Muhammad Ali, who became Pasha of Egypt in 1805, introduced the first national flag of Egypt, red with three white crescents, each accompanied by a white star.

The association of the crescent with the Ottoman Empire appears to have resulted in a gradual association of the crescent shape with Islam in the 20th century. A Red Crescent appears to have been used as a replacement of the Red Cross as early as in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/8, and it was officially adopted in 1929.

While some Islamic organisations since the 1970s have embraced the crescent as their logo or emblem (e.g. Crescent International magazine, established 1980), some Muslim publications tend to emphasize that the interpretation of the crescent, historically used on the banners of Muslim armies, as a "religious symbol" of Islam was an error made by the "Christians of Europe".[22] The identification of the crescent as an "Islamic symbol" is mentioned by James Hastings as a "common error" to which "even approved writers on Oriental subjects" are prone as early as 1928.[23]

The crescent was used on a flag of the American Revolutionary War and was called the Liberty (or Moultrie) Flag.

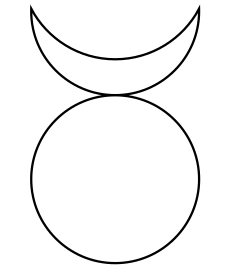

The symbol of the Triple Goddess is a circle flanked by a left facing and right facing crescent, which represents a maiden, mother and crone archetype.[24] The biohazard symbol bears peculiar resemblance to it.

Triple crescent badge of Henry II of France (Château d'Écouen)

Triple crescent badge of Henry II of France (Château d'Écouen) Mamluk lancers, early 16th century (etching by Daniel Hopfer)

Mamluk lancers, early 16th century (etching by Daniel Hopfer) The painting of the 1571 Battle of Lepanto by Tommaso Dolabella (c. 1632) shows a variety of naval flags with crescents attributed to the Ottoman Empire.

The painting of the 1571 Battle of Lepanto by Tommaso Dolabella (c. 1632) shows a variety of naval flags with crescents attributed to the Ottoman Empire. A naval battle painting of the Barbary state of Ottoman Algiers titled A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsairs by Laureys a Castro, c. 1681

A naval battle painting of the Barbary state of Ottoman Algiers titled A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsairs by Laureys a Castro, c. 1681 Madonna on the crescent, Bad Waldsee church (17th century)

Madonna on the crescent, Bad Waldsee church (17th century) Portrait of a Lady as Diana by Pompeo Batoni (1760s)

Portrait of a Lady as Diana by Pompeo Batoni (1760s) Symbol of the Triple Goddess

Symbol of the Triple Goddess A circle with an upward facing crescent representing the Wiccan Horned God

A circle with an upward facing crescent representing the Wiccan Horned God

Heraldry

The crescent has been used as a heraldic charge since the 13th century. In heraldic terminology, the term "crescent" when used alone refers to a crescent with the horns pointing upward. A crescent with the horns pointing left (dexter) is called "a crescent increscent" (or simply "an increscent"), and when the horns are pointing right (sinister), it is called "a crescent decrescent" (or "a decrescent"). A crescent with horns pointing down is called "a crescent reversed". Two crescents with horns pointing away from each other are called "addorsed".[25] Siebmachers Wappenbuch (1605) has 48 coats of arms with one or more crescents, for example:[26]

- Azure, a crescent moon argent pierced by an arrow fesswise Or all between in chief three mullets of six points and in base two mullets of six points argent (von Hagen, p. 176);

- Azure, an increscent and a decrescent addorsed Or (von Stoternheim, p. 146);

- Per pale Or and sable, a crescent moon and in chief three mullets of six points counterchanged (von Bodenstein, p. 182).

In English heraldry, the crescent is used as a difference denoting a second son.[25]

Three examples of coats of arms with crescents from the Dering Roll (c. 1270): No. 118: Willem FitzLel (sable crusily and three crescents argent); no. 120: John Peche (gules, a crescent or, on a chief argent two mullets gules); no. 128: Rauf de Stopeham (argent, two (of three) crescents and a canton gules).

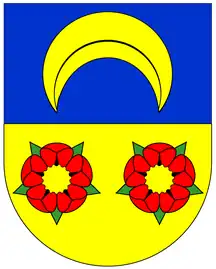

Three examples of coats of arms with crescents from the Dering Roll (c. 1270): No. 118: Willem FitzLel (sable crusily and three crescents argent); no. 120: John Peche (gules, a crescent or, on a chief argent two mullets gules); no. 128: Rauf de Stopeham (argent, two (of three) crescents and a canton gules). Coat of arms of the Neuamt bailiwick of Zürich (16th century).[27] Its reversed crescent was taken up in the 20th-century municipal coats of arms of Niederglatt, Neerach and Stadel (canton of Zürich).

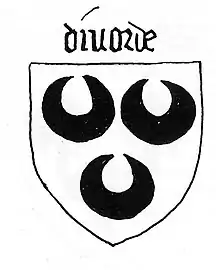

Coat of arms of the Neuamt bailiwick of Zürich (16th century).[27] Its reversed crescent was taken up in the 20th-century municipal coats of arms of Niederglatt, Neerach and Stadel (canton of Zürich). This coat of arms of the Divorde family (Holland and Brabant), around 1440, shows three crescents.

This coat of arms of the Divorde family (Holland and Brabant), around 1440, shows three crescents. Inverted crescent on Polish coat of arms.

Inverted crescent on Polish coat of arms.

Contemporary use

The crescent remains in use as astrological symbol and astronomical symbol representing the Moon. Use of a standalone crescent in flags is less common than the star and crescent combination. Crescents without stars are found in the South Carolina state flag (1861), All India Muslim League (1906-1947), the flag of Maldives (1965), the flag of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (1981)[28] and the flag of the Arab League.

New Orleans is nicknamed "the Crescent City", and a crescent (or crescent and star) is used to represent the city in official emblems.[29]

Crescents, often with faces, are found on numerous modern municipal coats of arms in Europe, e.g. Germany: Bönnigheim, Dettighofen, Dogern, Jesenwang, Karstädt, Michelfeld (Angelbachtal), Waldbronn; Switzerland: Boswil, Dättlikon, Neerach (from the 16th-century Neuamt coat of arms); France: Katzenthal, Mortcerf; Malta: Qormi; Sweden: Trosa.

The crescent printed on military ration boxes is the US Department of Defense symbol for subsistence items. The symbol is used on packaged foodstuffs but not on fresh produce or on items intended for resale.[30]

Since 1993, the crescent has also been in use as chaplain badge for Muslim chaplains in the US military.[2]

Flag of South Carolina (1861)

Flag of South Carolina (1861) Flag of Maldives (1965)

Flag of Maldives (1965) The emblem of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement around the world

The emblem of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement around the world Symbol of the Nationalist Movement Party of Turkey

Symbol of the Nationalist Movement Party of Turkey The Dreamliner logo is painted on many Boeing 787s

The Dreamliner logo is painted on many Boeing 787s Coat of arms of the 1st-54 Regulares Battalion "Tetuán" (Spanish Army)

Coat of arms of the 1st-54 Regulares Battalion "Tetuán" (Spanish Army)

Other things called "crescent"

The term crescent may also refer to objects with a shape reminiscent of the crescent shape, such as houses forming an arc, a type of solitaire game, Crescent Nebula, glomerular crescent (crescent shaped scar of the glomeruli of the kidney),[31][32] the Fertile Crescent (the fertile area of land between Mesopotamia and Egypt roughly forming a crescent shape), and the croissant (the French form of the word) for the crescent-shaped pastry.

See also

Notes

- from Middle English cressaunt 'crescent-shaped ornaments'; from Old French creissant 'crescent shape'; from Latin crēscēns 'growing, waxing'.

See e.g. the following:- "crescent". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- "crescent". CollinsDictionary.com. HarperCollins.

- "crescent". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-10-22. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- On December 14, 1992, the Army Chief of Chaplains requested that an insignia be created for future Muslim chaplains, and the design (a crescent) was completed January 8, 1993. Emerson, William K., Encyclopedia of United States Army Insignia and Uniforms (1996), p. 269f. Prior to its association with Islam, a crescent badge had already been used in the US military for the rank of commissary sergeant (Emerson 1996:261f).

- Alchemy and Symbols, By M. E. Glidewell, Epsilon.

- Neugebauer, Otto; Van Hoesen, H. B. (1987). Greek Horoscopes. pp. 1, 159, 163.

- "Bianchini's planisphere". Florence, Italy: Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza (Institute and Museum of the History of Science). Archived from the original on 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2010-03-19. Maunder, A. S. D. (1934). "The origin of the symbols of the planets". The Observatory. 57: 238–247. Bibcode:1934Obs....57..238M.

- The new Moon at sunset and the old Moon at sunrise, when observed with horns pointing upward, is also known as "wet moon" in English, in an expression loaned from Hawaiian culture.

- Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry (1909), p. 289. Online texts at https://archive.org/details/completeguidetoh00foxduoft or http://www7b.biglobe.ne.jp/~bprince/hr/foxdavies/index.htm .

- A.H. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs. 3rd Ed., pub. Griffith Institute, Oxford, 1957 (1st edition 1927), p. 486.

- Tombs and Moon Temple of Hureidah, Gertrude Caton Thompson, p.76

- "the three celestial emblems, the sun disk of Shamash (Utu to the Sumerians), the crescent of Sin (Nanna), and the star of Ishtar (Inanna to the Sumerians)". Irving L. Finkel, Markham J. Geller, Sumerian Gods and Their Representations, Styx, 1997, p71.

- Bell, s.v. Selene; Roman Sarcophagi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978, p. 35

- British Museum 1923,0401.199; LIMC 13213 (Selene, Luna 21); LIMC 13181 (Selene, Luna 4)

- Quail 1994, pp. 14–18.

- Tipaldos, G. E., Great Greek Encyclopedia, Vol. XII, page 292, Athens, 1930

- Oleg Grabar, "Umayyad Dome," Ars orientalis (1959), p. 50, cited after Berger (2012:164).

- Pamela Berger, The Crescent on the Temple: The Dome of the Rock as Image of the Ancient Jewish Sanctuary (2012), p. 164f

- Znamierowski Flags through the ages: A guide to the world of flags, banners, standards and ensigns, (2000) section 'the Muslim crescent', cited by Ivan Sache, FOTW Archived 2016-03-22 at the Wayback Machine, 11 March 2001

- "After king Nasr ad din had fled to Cairo in 1397 to beg assistance against his cousin, the King of Nubia is depicted with a yellow flag with a white crescent but also with a yellow shield with a white crescent. At the same time the yellow crescented flag waves over all the Mameluk Empire. The flag of the Sultan of Egypt is yellow with three white crescents. From this we may conclude that any autonomy of the Nubian king was over at the time." Hubert de Vries, Muslim Nubia (hubert-herald.nl).

- so for Jaffa (29r), Raman (31v-32r), Jerusalem (35v-36r). Grünenberg's pilgrimage took place still during the late Mamluk era (Burji dynasty) of control over the Holy Land.

- Agostino Barberigo, L' ultimo Et vero Ritrato Di la vitoria de L'armata Cristiana de la santissima liga Contre a L'armata Turcheschà [...], 1571. Antonio Lafreri , L’ordine tenuto dall’armata della santa Lega Christiana contro il Turcho [...], n'e seguita la felicissima Vittoria li sette d'Ottobre MDLXXI [...], Rome, 1571

- İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Vol. 4. Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı. 1991. p. 298.

- "Like the Crusaders, the Christians of Europe were misled into a belief that the crescent was the religious symbol of Islam" Islamic Review 30 (1942), p. 70., "many Muslim scholars reject using the crescent moon as a symbol of Islam. The faith of Islam historically had no symbol, and many refuse to accept it.", Fiaz Fazli, Crescent magazine, Srinagar, September 2009, p. 42.

- "There is no more common error than the supposition that the crescent (or rather crescent and star) is an Islamic symbol, and even approved writers on Oriental subjects are apt to fall into it." James Hastings, Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, Volumes 11-12 (1928), p. 145.

- Gilligan, Stephen G., and Simon, Dvorah (2004). Walking in Two Worlds: The Relational Self in Theory, Practice, and Community. Zeig Tucker & Theisen Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 1-932462-11-2, ISBN 978-1-932462-11-1. Retrieved 03 January 2022.

- Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, A complete guide to heraldry (1909), p. 289.

- Sara L. Uckelman, An Ordinary of Siebmacher's Wappenbuch (ellipsis.cx) (2014)

- geteilt von Blau mit gestürztem goldenem Halbmond und von Gold mit zwei roten Rosen ("per fess azure a crescent reversed or and of the second two roses gules") Historisch-Biographisches Lexikon der Schweiz, vol. V, p. 243.

- In 2011 replaced with a logo showing a crescent engulfing the globe. "Ihsanoglu urges international community to recognize state of Palestine at the United Nations, historic change of OIC logo and name to Organisation of the Islamic Cooperation". Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. 28 June 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- "History of the NOPD Badge". Archived from the original on 2013-07-24. The origin is the crescent shape of the old city, hugging the East Bank of the Mississippi River.

- MIL STD 129, FM 55-17

- . It is a sign of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (also called crescentic glomerulonephritis). "iROCKET Learning Module: Glomerular Pathology, Case I". Archived from the original on December 12, 2012.

- "Renal Pathology".

References

- Bell, Robert E., Women of Classical Mythology: A Biographical Dictionary, ABC-CLIO 1991, ISBN 0-87436-581-3. Internet Archive.

- Quail, Sarah (1994). The Origins of Portsmouth and the First Charter. City of Portsmouth. ISBN 0-901559-92-X.