Deferasirox

Deferasirox, sold under the brand name Exjade & Asunra (in injectable form) & Oleptiss (Tablet formulation) both by Novartis among others, is an oral iron chelator. Its main use is to reduce chronic iron overload in patients who are receiving long-term blood transfusions for conditions such as beta-thalassemia and other chronic anemias.[2][3] It is the first oral medication approved in the United States for this purpose.[4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | de FER a sir ox |

| Trade names | Exjade, Jadenu |

| Other names | CGP-72670, ICL-670A, IC L670 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 70% |

| Protein binding | 99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic glucuronidation |

| Elimination half-life | 8 to 16 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal (84%) and renal (8%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.211.077 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H15N3O4 |

| Molar mass | 373.368 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.4±0.1 g/cm3 [1] |

| |

| |

| | |

It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in November 2005.[2][4] According to the FDA (May 2007), kidney failure and cytopenias have been reported in patients receiving deferasirox tablets for oral suspension. It is approved in the European Union by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for children six years and older for chronic iron overload from repeated blood transfusions.[5][6][7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8]

In July 2020, Teva decided to discontinue deferasirox.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[10]

Properties

_complex.png.webp)

The half-life of deferasirox is between 8 and 16 hours allowing once a day dosing. Two molecules of deferasirox are capable of binding to 1 atom of iron which are subsequently eliminated by fecal excretion. Its low molecular weight and high lipophilicity allows the drug to be taken orally unlike deferoxamine which has to be administered by IV route (intravenous infusion). Together with deferiprone, deferasirox seems to be capable of removing iron from cells (cardiac myocytes and hepatocytes) as well as removing iron from the blood.

Synthesis

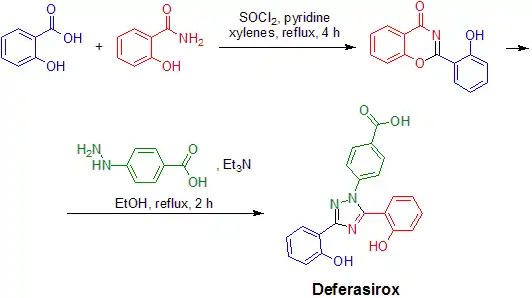

Deferasirox can be prepared from simple commercially available starting materials (salicylic acid, salicylamide and 4-hydrazinobenzoic acid) in the following two-step synthetic sequence:

The condensation of salicyloyl chloride (formed in situ from salicylic acid and thionyl chloride) with salicylamide under dehydrating reaction conditions results in formation of 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1,3(4H)-benzoxazin-4-one. This intermediate is isolated and reacted with 4-hydrazinobenzoic acid in the presence of base to give 4-(3,5-bis(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)benzoic acid (deferasirox).[11]

Risks

Deferasirox ranked second on the list of drugs most frequently suspected in reported patient deaths compiled for 2019 by the Institute for Safe Medical Practices, with 1320 suspected deaths.[12] A boxed warning was added in the same year with regard to kidney failure, liver failure and gastrointestinal bleeding.[13] It is suspected that the main driver of this spike in suspected deaths relates to the re-analysis of adverse event data by Novartis.[12]

References

- "Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS): Deferasirox". ChemSrc. 2018.

- Choudhry VP, Naithani R (August 2007). "Current status of iron overload and chelation with deferasirox". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 74 (8): 759–64. doi:10.1007/s12098-007-0134-7. PMID 17785900. S2CID 19930076. Free full text Archived 2014-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Yang LP, Keam SJ, Keating GM (2007). "Deferasirox : a review of its use in the management of transfusional chronic iron overload". Drugs. 67 (15): 2211–30. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767150-00007. PMID 17927285.

- "FDA Approves First Oral Drug for Chronic Iron Overload" (Press release). United States Food and Drug Administration. November 9, 2005. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- "Exjade – deferasirox" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 2018.

- Kontoghiorghes GJ (April 2013). "Turning a blind eye to deferasirox's toxicity?". Lancet. 381 (9873): 1183–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60799-0. PMID 23561999. S2CID 27794849.

- "Review: Exjade side effects".

- World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- "Deferasirox Discontinuation". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Steinhauser S, Heinz U, Bartholomä M, Weyhermüller T, Nick H, Hegetschweiler K (2004). "Complex Formation of ICL670 and Related Ligands with FeIII and FeII". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2004 (21): 4177–4192. doi:10.1002/ejic.200400363.]

- "QuarterWatch™ (Quarter 4 and 2009 totals): Reported Patient Deaths Increased by 14% in 2009". Institute For Safe Medication Practices. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- Pediatrics, American Academy of (2010-02-19). "Black box warning added to Exjade". AAP News. doi:10.1542/aapnews.20100219-1 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 1073-0397. Archived from the original on 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link)