Cy Young

Denton True "Cy" Young (March 29, 1867 – November 4, 1955) was an American Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher. Born in Gilmore, Ohio, he worked on his family's farm as a youth before starting his professional baseball career. Young entered the major leagues in 1890 with the National League's Cleveland Spiders and pitched for them until 1898. He was then transferred to the St. Louis Cardinals franchise. In 1901, Young jumped to the American League and played for the Boston Red Sox franchise until 1908, helping them win the 1903 World Series. He finished his career with the Cleveland Naps and Boston Rustlers, retiring in 1911.

| Cy Young | |

|---|---|

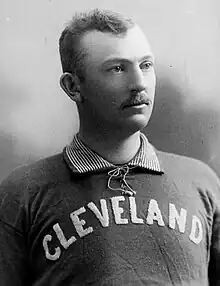

Young with the Cleveland Naps in 1911 | |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: March 29, 1867 Gilmore, Ohio, U.S. | |

| Died: November 4, 1955 (aged 88) Newcomerstown, Ohio, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| August 6, 1890, for the Cleveland Spiders | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 11, 1911, for the Boston Rustlers | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 511–315 |

| Earned run average | 2.63 |

| Strikeouts | 2,803 |

| Teams | |

As player

As manager | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

MLB records

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1937 |

| Vote | 76.12% (second ballot) |

Young was one of the hardest-throwing pitchers in the game early in his career. After his speed diminished, he relied more on his control and remained effective into his forties. By the time Young retired, he had established numerous pitching records, some of which have stood for over a century. He holds MLB records for the most career wins, with 511, along with most career losses, innings pitched, games started, and complete games. He led his league in wins during five seasons and pitched three no-hitters, including a perfect game in 1904.

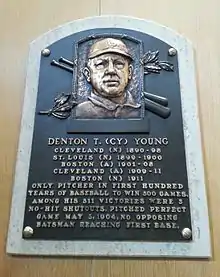

Young was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937. He is often regarded as one of the greatest pitchers of all time, as well as a pioneer of modern pitching. In 1956, one year after his death, the Cy Young Award was created to annually honor the best pitcher in the Major Leagues (later each League) of the previous season, cementing his name as synonymous with excellence in pitching.

Early life

Cy Young was the oldest child born to Nancy (Mottmiller) and McKinzie Young, Jr., and was christened Denton True Young. He was of part German descent. The couple had four more children: Jesse Carlton, Alonzo, Ella, and Anthony. When the couple married, McKinzie's father gave him the 54 acres (220,000 m2) of farm land he owned.[1] Young was born in Gilmore, a tiny farming community located in Washington Township, Tuscarawas County, Ohio. He was raised on one of the local farms and went by the name Dent Young in his early years.[2] Young was also known as "Farmer Young" and "Farmboy Young". Young stopped his formal education after he completed the sixth grade[3] so he could help out on the family's farm. In 1885, Young moved with his father to Nebraska, and in the summer of 1887, they returned to Gilmore.

Young played for many amateur baseball leagues during his youth, including a semi-professional Carrollton team in 1888. Young pitched and played second base. The first box score known containing the name Young came from that season. In that game, Young played first base and had three hits in three at-bats. After the season, Young received an offer to play for the minor league Canton team, which started Young's professional career.[1]

Professional career

Minor leagues

Young began his professional career in 1889 with the Canton, Ohio, team of the Tri-State League, a professional minor league. During his tryout, Young impressed the scouts, recalling years later, "I almost tore the boards off the grandstand with my fast ball."[4] Cy Young's nickname came from the fences that he had destroyed using his fastball. The fences looked like a cyclone had hit them. Reporters later shortened the name to "Cy", which became the nickname Young used for the rest of his life.[5] During his one year with Canton, he was 15-15.[2]

Franchises in the National League, the major professional baseball league at the time, wanted the best players available to them. Therefore, in 1890, Young signed with the Cleveland Spiders, a team which had moved from the American Association to the National League the previous year.

Cleveland Spiders (1890–1898)

On August 6, 1890, Young's major league debut, he pitched a three-hit 8–1 victory over the Chicago Colts.[6] While Young was with the Spiders, Chief Zimmer was his catcher more often than any other player. Bill James, a baseball statistician, estimated that Zimmer caught Young in more games than any other battery in baseball history.[7] Early on, Young established himself as one of the harder-throwing pitchers in the game. Bill James wrote that Zimmer often put a piece of beefsteak inside his baseball glove to protect his catching hand from Young's fastball.[7] In the absence of radar guns, however, it is impossible to say just how hard Young actually threw. Young continued to perform at a high level during the 1890 season. On the last day of the season, Young won both games of a doubleheader.[3] In the first weeks of Young's career, Cap Anson, the player-manager of the Chicago Colts spotted Young's ability. Anson told Spiders manager Gus Schmelz, "He's too green to do your club much good, but I believe if I taught him what I know, I might make a pitcher out of him in a couple of years. He's not worth it now, but I'm willing to give you $1,000 ($32,570 today) for him." Schmelz replied, "Cap, you can keep your thousand and we'll keep the rube."[8]

Two years after Young's debut, the National League moved the pitcher's position back by 5 feet (1.5 m). Since 1881, pitchers had pitched within a "box" whose front line was 50 feet (15 m) from home base, and since 1887 they had been compelled to toe the back line of the box when delivering the ball. The back line was 55 feet 6 inches (16.92 m) away from home. In 1893, 5 feet (1.5 m) was added to the back line, yielding the modern pitching distance of 60 feet 6 inches (18.44 m). In the book The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, sports journalist Rob Neyer wrote that the speed with which pitchers like Cy Young, Amos Rusie, and Jouett Meekin threw was the impetus that caused the move.[9]

The 1892 regular season was a success for Young, who led the National League in wins (36), ERA (1.93), and shutouts (9). Just as many contemporary Minor League Baseball leagues operate today, the National League was using a split season format during the 1892 season.[10] The Boston Beaneaters won the first-half and the Spiders won the second-half, with a best-of-nine series determining the league champion. Despite the Spiders' second-half run, the Beaneaters swept the series, five games to none. Young pitched three complete games: he lost two and one ended in a scoreless tie.

The Spiders faced the Baltimore Orioles in the Temple Cup, a precursor to the World Series, in 1895. Young won three games in the series and Cleveland won the Cup, four games to one. It was around this time that Young added what he called a "slow ball" to his pitching repertoire to reduce stress on his arm. The pitch today is called a changeup.[3] In 1896, Young lost a no-hitter with two outs in the ninth inning when Ed Delahanty of the Philadelphia Phillies hit a single.[11] On September 18, 1897, Young pitched the first no-hitter of his career in a game against the Cincinnati Reds. Although Young did not walk a batter, the Spiders committed four errors while on defense. One of the errors had originally been ruled a hit, but the Cleveland third baseman sent a note to the press box after the eighth inning, saying he had made an error, and the ruling was changed. Young later said that, despite his teammate's gesture, he considered the game to be a one-hitter.[12]

St. Louis Perfectos / Cardinals (1899–1900)

Prior to the 1899 season, Frank Robison, the Spiders owner, bought the St. Louis Browns, thus owning two clubs simultaneously. The Browns were renamed the "Perfectos", and restocked with Cleveland talent. Just weeks before the season opener, most of the better Spiders players were transferred to St. Louis, including three future Hall of Famers: Young, Jesse Burkett, and Bobby Wallace.[13] The roster maneuvers failed to create a powerhouse Perfectos team, as St. Louis finished fifth in both 1899 and 1900. Meanwhile, the depleted Spiders lost 134 games, the most in MLB history, before folding. Young spent two years with St. Louis, which is where he found his favorite catcher, Lou Criger. The two men were teammates for a decade.[3][14]

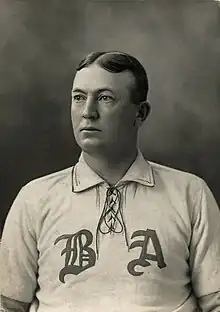

Boston Americans / Red Sox (1901–1908)

In 1901, the rival American League declared major league status and set about raiding National League rosters. Young left St. Louis and joined the American League's Boston Americans for a $3,500 contract ($123,116 today). Young would remain with the Boston team until 1909. In his first year in the American League, Young was dominant. Pitching to Criger, who had also jumped to Boston, Young led the league in wins, strikeouts, and ERA[b], thus earning the colloquial AL Triple Crown for pitchers.[15] Young won almost 42% of his team's games in 1901, accounting for 33 of his team's 79 wins.[16] In February 1902, before the start of the baseball season, Young served as a pitching coach at Harvard University. The sixth-grade graduate instructing Harvard students delighted Boston newspapers.[3] The following year, Young coached at Mercer University during the spring. The team went on to win the Georgia state championship in 1903, 1904, and 1905.[17]

The Boston Americans played the Pittsburgh Pirates in the first modern World Series in 1903. Young, who started Game One against the visiting Pirates, thus threw the first pitch in modern World Series history. The Pirates scored four runs in that first inning, and Young lost the game. Young performed better in subsequent games, winning his next two starts. He also drove in three runs in Game Five. Young finished the series with a 2–1 record and a 1.85 ERA in four appearances, and Boston defeated Pittsburgh, five games to three.

After one-hitting Boston on May 2, 1904, Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Rube Waddell taunted Young to face him so that he could repeat his performance against Boston's ace. Three days later, Young pitched a perfect game against Waddell and the Athletics.[a2] It was the first perfect game in American League history.[a3][18][19] Waddell was the 27th and last batter, and when he flied out, Young shouted, "How do you like that, you hayseed?"

Waddell had picked an inauspicious time to issue his challenge. Young's perfect game was the centerpiece of a pitching streak. Young set major league records for the most consecutive scoreless innings pitched and the most consecutive innings without allowing a hit; the latter record still stands at 25.1 innings, or 76 hitless batters.[20][21] Even after he allowed a hit, Young's scoreless streak reached a then-record 45 shutout innings. Before Young, only two pitchers had thrown perfect games.[a3] This occurred in 1880, when Lee Richmond and John Montgomery Ward pitched perfect games within five days of each other, although under somewhat different rules: the front edge of the pitcher's box was only 45 feet (14 m) from home base (the modern release point is about 10 feet (3.0 m) farther away); walks required eight balls; and pitchers were obliged to throw side-armed. Young's perfect game was the first under the modern rules established in 1893. One year later, on July 4, 1905, Rube Waddell beat Young and the Americans, 4–2, in a 20-inning matchup. Young pitched 13 consecutive scoreless innings before he gave up a pair of unearned runs in the final inning. Young did not walk a batter and was later quoted: "For my part, I think it was the greatest game of ball I ever took part in."[22] In 1907, Young and Waddell faced off in a scoreless 13-inning tie.

In 1908, Young pitched the third no-hitter of his career. Three months past his 41st birthday, he was the oldest pitcher to record a no-hitter, a record which would stand 82 years until 43-year-old Nolan Ryan broke it. Only a walk kept Young from his second perfect game. After that runner was caught stealing, no other batter reached base. At the time, Young was the second-oldest player in either league. In another game one month before his no-hitter, he allowed just one single while facing 28 batters.[16] On August 13, 1908, the league celebrated "Cy Young Day". No American League games were played on that day, and a group of All-Stars from the league's other teams gathered in Boston to play against Young and the Red Sox.[23] When the season ended, he posted a 1.26 ERA, which gave him not only the lowest in his career, but also a major league record of being the oldest pitcher with 150+ innings and an ERA under 1.50.

Cleveland Naps (1909–1911)

Young was traded back to Cleveland, the place where he played over half his career, before the 1909 season, to the Cleveland Naps of the American League. The following season, 1910, he won his 500th career game on July 19 against Washington.[24][25]

Boston Rustlers (1911) and retirement

He split 1911, his final year, between the Naps and the Boston Rustlers. On September 22, 1911, Young shut out the Pittsburgh Pirates, 1–0, for his last career victory.[26] In his final start two weeks later, the last eight batters of Young's career combined to hit a triple, four singles, and three doubles.[27] By the time of his retirement, Young's control had faltered. He had also gained weight.[3] In two of his last three years, he was the oldest player in the league.[15]

Career accomplishments

Young established numerous pitching records, some of which have stood for over a century. Young compiled 511 wins, which is the most in major league history and 94 ahead of Walter Johnson, second on the list.[28] At the time of Young's retirement, Pud Galvin had the second most career wins with 364. In addition to wins, Young still holds the major league records for most career innings pitched (7,356), most career games started (815), and most complete games (749).[29][30][31] He also retired with 316 losses, the most in MLB history.[32] Young's career record for strikeouts was broken by Johnson in 1921.[33] Young's 76 career shutouts are fourth all-time.[34]

Y is for Young

The magnificent Cy;

People batted against him,

But I never knew why.

— Ogden Nash, Sport magazine (January 1949)[35]

Young led his league in wins five times (1892, 1895, and 1901–1903), finishing second twice. His career high was 36 in 1892. He won at least 30 games in a season five times. He had 15 seasons with 20 or more wins, two more than Christy Mathewson and Warren Spahn. Young won two ERA titles during his career, in 1892 (1.93) and in 1901 (1.62), and was three times the runner-up. Young's earned run average was below 2.00 six times, but it was not uncommon during the dead-ball era. Although Young threw over 400 innings in each of his first four full seasons, he did not lead his league until 1902. He had 40 or more complete games nine times. Young also led his league in strikeouts twice (140 in 1896 and 158 in 1901), and in shutouts seven times.[15] Young led his league in fewest walks per nine innings fourteen times and finished second once. Only twice in his 22-year career did he finish lower than 5th in the category. Although the WHIP ratio was not calculated until well after Young's death, he was retroactively league leader seven times and was second or third another seven times.[15]

Young is tied with Roger Clemens for the most career wins by a Boston Red Sox pitcher: they each won 192 games while with the franchise.[36] In addition, Young pitched three no-hitters, including the third perfect game in baseball history, first in baseball's "modern era". Young also was an above average hitting pitcher. He posted a .210 batting average (623-for-2960) with 325 runs, 290 RBIs, 18 home runs, and 81 walks. From 1891 through 1905, he drove in 10 or more runs for 15 straight seasons, with a high of 28 in 1896.[15]

Pitching style

Particularly after his fastball slowed, Young relied upon his control. He was once quoted as saying, "Some may have thought it was essential to know how to curve a ball before anything else. Experience, to my mind, teaches to the contrary. Any young player who has good control will become a successful curve pitcher long before the pitcher who is endeavoring to master both curves and control at the same time. The curve is merely an accessory to control."[8] In addition to his exceptional control, Young was also a workhorse who avoided injury, owing partly to his ability to pitch in different arm positions (overhand, three-quarters, sidearm and even submarine). For 19 consecutive years, from 1891 through 1909, Young was in his league's top 10 for innings pitched; in 14 of the seasons, he was in the top five. Not until 1900, a decade into his career, did Young pitch two consecutive incomplete games.[12] By habit, Young restricted his practice throws in spring training. "I figured the old arm had just so many throws in it," said Young, "and there wasn't any use wasting them." He once described his approach before a game:

I never warmed up ten, fifteen minutes before a game like most pitchers do. I'd loosen up, three, four minutes. Five at the outside. And I never went to the bullpen. Oh, I'd relieve all right, plenty of times, but I went right from the bench to the box, and I'd take a few warm-up pitches and be ready. Then I had good control. I aimed to make the batter hit the ball, and I threw as few pitches as possible. That's why I was able to work every other day.[8]

Managerial record

| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| BOA | 1907 | 6 | 3 | 3 | .500 | resigned* | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 6 | 3 | 3 | .500 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

* Stepped down to a player only role.

Later life

In 1910, it was reported that Young was a vegetarian.[37] Beginning in 1912, Young lived and worked on his farm. In 1913, he served as manager of the Cleveland Green Sox of the Federal League, which was at the time an outlaw league. However, he never worked in baseball after that.

In 1916, he ran for county treasurer in Tuscarawas County, Ohio.[39]

Young's wife, Roba,[40] whom he had known since childhood, died in 1933.[1][3] After she died, Young tried several jobs, and eventually moved in with friends John and Ruth Benedum and did odd jobs for them. Young took part in many baseball events after his retirement.[3] In 1937, 26 years after he retired from baseball, Young was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He was among the first to donate mementos to the Hall.

By 1940, Young's only source of income was stock dividends of $300 per year ($6,267 today).[1][41] On November 4, 1955, Young died on the Benedums' farm at the age of 88.[1] He was buried in Peoli, Ohio.[42]

Legacy

Young's career is seen as a bridge from baseball's earliest days to its modern era; he pitched against stars such as Cap Anson, already an established player when the National League was first formed in 1876, as well as against Eddie Collins, who played until 1930. When Young's career began, pitchers delivered the baseball underhand and fouls were not counted as strikes. The pitcher's mound was not moved back to its present position of 60 feet 6 inches (18.44 m) until Young's fourth season; he did not wear a glove until his sixth season.[3]

Young was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937. In 1956, about one year after Young's death, the Cy Young Award was created to honor the best pitcher in Major League Baseball for each season. The first award was given to Brooklyn's Don Newcombe. Originally, it was a single award covering all of baseball. The honor was divided into two Cy Young Awards in 1967, one for each league.

On September 23, 1993, a statue dedicated to him was unveiled by Northeastern University on the site of the Red Sox's original stadium, the Huntington Avenue Grounds. It was there that Young had pitched the first game of the 1903 World Series, as well as the first perfect game in the modern era of baseball. A home plate-shaped plaque next to the statue reads:

On October 1, 1903 the first modern World Series between the American League champion Boston Pilgrims (later known as the Red Sox) and the National League champion Pittsburgh Pirates was played on this site. General admission tickets were fifty cents. The Pilgrims, led by twenty-eight game winner Cy Young, trailed the series three games to one but then swept four consecutive victories to win the championship five games to three.[43]

In 1999, 88 years after his final major league appearance and 44 years after his death, editors at The Sporting News ranked Young 14th on their list of "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players".[44] That same year, baseball fans named him to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

See also

- 300-win club

- List of Major League Baseball career wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career shutout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hit batsmen leaders

- Triple Crown (baseball)

- List of Major League Baseball annual wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual shutout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual saves leaders

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball no-hitters

- List of Major League Baseball individual streaks

- List of Major League Baseball player-managers

- List of Major League Baseball all-time leaders in home runs by pitchers

- Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame

Notes

- a.^ [a2][a3] Although the phrase "perfect game" appeared in record books as early as 1922, and was a common expression years before that, Major League Baseball did not formalize the definition of a "perfect game" until 1991, long after Young's death. Nonetheless, Young's 1955 obituary also used the phrase.

- "An official perfect game occurs when a pitcher (or pitchers) retires each batter on the opposing team during the entire course of a game, which consists of at least nine innings. In a perfect game, no batter reaches any base during the course of the game."[45]

- b.^ Although it is not an actual award, many baseball fans and experts call a pitcher who leads his league in wins, strikeouts, and ERA the Triple Crown winner in pitching.

References

- Browning, Reed (2003). Cy Young: A Baseball Life. Univ of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-398-0.

- "Cy Young Biography". CMG Worldwide. Archived from the original on June 2, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- "Baseball Book Review: Cy Young : A Life In Baseball". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- "Cy Young Obituary". The New York Times. November 5, 1955. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- "The Ballplayers – Cy Young". Baseball Biography. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- "1890 Chronology". Baseball Library. Archived from the original on May 26, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Abstract (Simon & Schuster, 2001), pp. 410–411

- "Cy Young: Quotes". CMG Worldwide. Archived from the original on December 29, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- Neyer, Rob; Bill James (June 2004). The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. Fireside. pp. 496. ISBN 0-7432-6158-5.

- Gietschier, Steve (November 15, 1993). "Of double seasons, Spiders and no fall stakes". The Sporting News. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2008 – via HighBeam.

- "1896 Chronology". Baseball Library. Archived from the original on May 25, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- "1897 Chronology". Baseball Library. Archived from the original on May 31, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- Fleitz, David. "The 1899 Cleveland Spiders". wcnet. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- "Biography:Cy Young". answers.com. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- "Cy Young Statistics". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- "Cy Young from the Chronology". Baseball Library. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- Spright Dowell, A History of Mercer University, 1833–1953 Archived February 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (Macon, Georgia: Mercer University, [1958]).

- "Hall of Fame profile". Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on December 19, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- "Cy Young Perfect Game Box Score". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- "Clarifying Some of the Records*". Society for American Baseball Research. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011.

- Peticca, Mike (July 27, 2011). "No-hitters: Did you ever attend a record-book type major league game? Tell us your memories". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012.

- "Waddell vs Young". By Daniel O’Brien. Philadelphia Athletics. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- "Cy Young Day". brainyhistory.com. Retrieved November 11, 2006.

- Cleveland Naps Schedule Baseball Almanac. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Cy Young's Great Record" New York Times. July 24, 1910. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Boston Rustlers 1, Pittsburgh Pirates 0". Retrosheet. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- "Brooklyn Superbas 13, Boston Rustlers 3 (2)". Retrosheet. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- "Career Leaders for Wins". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "Innings Pitched Records". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "Games Started Records". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "Complete Games Records". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "Games Lost Records". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- SABR, p.210, ISBN 978-1-4165-3245-3 Retrieved on August 3, 2008

- "Pitching Leaders, Career All Time". mlb.com. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- Ogden Nash. "Line-Up For Yesterday by Ogden Nash". Sport Magazine. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- "Boston Red Sox All-Time Leaders". Boston Red Sox. MLB. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- Shprintzen, Adam D. (2013). The Vegetarian Crusade: The Rise of an American Reform Movement, 1817-1921. University of North Carolina Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-4696-0891-4

- "Masons in Baseball". Lodge No. 43, F. & A. M. August 24, 2014. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- "1916 Cy Young County Treasurer Promotional Card". Pre-War Cards. September 8, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- File:Cy Young, Roba Miller Young Tombstone.JPG

- "1940 United States Census – Denton Young". FamilySearch. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- "Cy Young". Retrosheet. Retrieved November 11, 2006.

- Boston's Pastime. "Huntington Avenue Grounds: The Pre-Fenway Era". Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players". The Sporting News. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "The Official Site of Major League Baseball: Official Info: Rules, regulations and statistics". MLB. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Cy Young managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Cy Young at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Jane Benedum Oral History Interview on Cy Young (1 of 2) - National Baseball Hall of Fame Digital Collection Archived July 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Jane Benedum Oral History Interview on Cy Young (2 of 2) - National Baseball Hall of Fame Digital Collection