Dervish movement (Somali)

The Dervish Movement (Somali: Dhaqdhaqaaqa Daraawiish) was a popular movement between 1896 and 1925, which was led by the Salihiyya Sufi Muslim poet and militant leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, also known as Sayyid Mohamed, who called for independence from the British and Italian colonies and the defeat of Ethiopian forces.[1][2][3][4][5] The Dervish movement aimed to remove the British and Italian influence from the region and restore the "Sufi system of governance with Sufi education as its foundation", according to Mohamed-Rahis Hasan and Salada Robleh.[6]

Dervish Movement Dhaqdhaqaaqa Daraawiish | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1896[1][2][3]–1925 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Nugal, Somalia (1905–1909) Taleh (1913–1920) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Somali | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Somali | ||||||||

| Leader | |||||||||

• 1899–1920 | Mohammed Abdullah Hassan | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1896[1][2][3] | ||||||||

• Capture of Jigjiga region | 1900 | ||||||||

• Signing of Ilig Treaty, Nugaal Valley is ceded to the Dervish | 1905 | ||||||||

• Invasion of British Somaliland Inflicting mass casualties on the British Empire and British Retreat to costal regions | 1909 | ||||||||

| 1914-1918 | |||||||||

• Decline of State | 1919 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 9 February 1925 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• | c. 1,000,000 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Somalia Ethiopia | ||||||||

Hassan established a ruling council called the Khususi consisting of Sufi tribe seniors and spokesman, added an adviser from the Ottoman Empire named Muhammad Ali and thus created a multi-clan Islamic movement in what led to the eventual creation of the state of Somalia.[5][4][7]

The Dervish movement attracted between 25,000 and 26,000 youth from different clans over 1896 and 1905, acquired firearms and then attacked the Ethiopian army in the Jigjiga region. The Ethiopians retreated and then gave the Dervishes their first military victory.[8][note 1] The Dervish movement then declared the colonial administration in British Somaliland as their enemy. To end the movement, the British sought out the competing Somali clans as coalition partners against the Dervish movement. The British provided these clans with firearms and supplies to fight against the Dervishes. Punitive attacks were launched against Dervish strongholds in 1904.[4][5] The Dervish movement suffered losses in the field, regrouped into smaller units and resorted to guerrilla warfare. Hasan and his loyalist Dervishes moved into the Italian-controlled Somaliland in 1905 after Hasan signed the Illig treaty, under which the Dervishes were ceded the Nugaal Valley,[10][11] which strengthened his movement,[4] and Hasan subsequently received an Italian subsidy and autonomous protected status.[12] In 1908, the Dervishes entered the British Somaliland again and began inflicting major losses to the British in the interior regions of the Horn of Africa. The British retreated to the coastal regions, leaving the chaotic interior regions in the hands of the Dervishes. During 1905-1910 the Dervishes lost much of their support due to their indiscriminate raids against allies and enemies alike, with several followers subsequently leaving the Dervishes after Hasan was supposedly excommunicated by the head of the Salihiyyah tariqa in Mecca in a famous letter.[13]

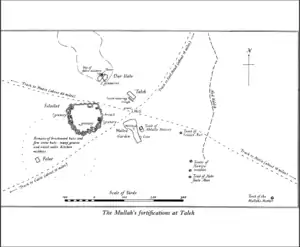

The First World War shifted the attention of the British elsewhere, although upon its conclusion, in 1920 the British launched a massive combined arms offensive on the Taleh forts, strongholds of the Dervish movement.[5][8] The offensive caused significant casualties among the Dervishes, although the Dervish leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan managed to escape. His death in 1921 due to either malaria or influenza ended the Dervish movement.[4][5][14]

The Dervish movement temporarily created a mobile Somali "proto-state" in early 20th-century with fluid boundaries and fluctuating population.[15] It was one of the bloodiest and longest militant movements in sub-Saharan Africa during the colonial era, one that overlapped with World War I. The battles between various sides over two decades killed nearly a third of Somaliland's population and ravaged the local economy.[14][16][17] Scholars variously interpret the emergence and demise of the militant Dervish movement in Somalia. Some consider the "Sufi Islamic" ideology as the driver, others consider economic crisis to the nomadic lifestyle triggered by the occupation and "colonial predation" ideology as the trigger for the Dervish movement, while post-modernists state that both religion and nationalism created the Dervish movement.[5]

History

Origins

According to Abdullah A. Mohamoud, traditional Somali society followed a decentralized structure and a nomadic lifestyle dependent on livestock and pastureland. It was also predominantly Muslim.[4][18] As the European colonial powers expanded their reach in the Horn of Africa, the region of Somalia came under the influence of the Ethiopians, the British and the Italians. Ethiopia on its part, focused more on the Ogaden region as its forces were ambushed and defeated by the Geledi in the Battle of Luuq despite having a large force of riflemen, artillery and horsemen. This caused Ethiopia to rethink its strategy of conquering the coastal southern region and focused on the hinterlands of the Ogaden.[19] With foreign rule came the centralization of the economy, which greatly upset the traditional livestock and pastureland based livelihood of the Somalis. The foreign powers were also all Christians, which created additional suspicions amongst the Somali religious elite.[18] The Ethiopian troops had already proved to be a bane for the Somalis as they were the traditional raiders and plunderers of their grazing herds due to the Dervish raids. The arrival of the colonial powers and the consequent partitioning of Africa greatly affected the Somalis, with Sufi poets such as Faarax Nuur writing poems expressing his opposition to foreign rule.[20] The Dervish movement can thus be seen as a reaction against the establishment of foreign control in Ethiopia.[18]

The Dervish movement was led by a Sufi poet and religious nationalist leader named Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, also known as Sayid Maxamad Cabdulle Xasan.[4] According to Said M. Mohamed, he was born in Sacmadeeqo sometime between 1856 and 1864 to a father who was a religious teacher.[4] He studied in Somali Islamic seminaries and later went on Hajj to Mecca where he met Shaykh Muhammad Salah of the Salihiya Islamic Tariqah, which states The Encyclopedia Britannica was a "militant, reformist, and puritanical Sufi order".[21][4] The preachings of Salah to Hasan had roots in Saudi Wahhabism, and it considered it a religious duty "to wage a holy war (jihad) against all other forms of Islam, the Western and Christian presence in the Muslim world, and a religious revival", state Richard Shultz and Andrea Dew.[14] When Hasan returned to the Horn of Africa, the Somali tradition states that he saw Somali children being converted to Christianity by missionaries in the British colony. Hasan began preaching against this religious conversion and the British presence. He earned the ire of the British colonial administration who termed him the 'mad mullah', and his Sufi teachings were also opposed by the rival Qadiriya Tariqah – another traditional Sufi group of the region, states Said M. Mohamed.[4][22] Another version of the early events link the illegal sale of a gun to Hasan by a corrupt Somali officer in 1899, who reported his gun as stolen rather than purchased by Hasan.[23] The British authorities demanded the gun's return, while Hasan replied that the British should leave the country, a sentiment he had previously claimed in 1897 when he declared himself "the leader of a sovereign nation".[23] Hasan continued to preach against the British introduction of Christianity to Somalia, stating that the "British infidels have destroyed our [Islamic] religion and made our children their children".[23]

Hasan left the urban settlement and moved to preach in the countryside. His influence spread in the rural parts and many elders, as well as youth, became his followers. Hasan converted the influenced youth from different clans into a Muslim brotherhood,[21] rallying to protect Islam from the influence of the Christian missionaries.[24] These formed the Hasan's armed resistance group to confront the colonial powers, and came to be known as Dervishes or Daraawiish, states Said M. Mohamed.[4]

Movement

The Dervish movement temporarily created a Somali "proto-state", according to Markus Hoehne.[15] It was a mobile state with fluid boundaries and fluctuating population given the guerilla style militant approach of Dervishes and their practice of retreating to sparsely inhabited hinterland whenever the colonial forces with superior firearms overwhelmed them. At the head of this state was the Sufi leader Hasan with the power of final decision. Hasan surrounded himself with a group of commanders for the militant operations supported by the khusuusi or the Dervish council. Islamic judges settled disputes and enforced the Islamic law in this Dervish state. According to Robert Hess, two of Hasan's chief advisors were Sultan Nur – previously Habr Yunis chief, and Haji Sudi Shabeel also known as Ahmad Warsama from Adan Madoba Habr Je'lo who was fluent in English.[25][26]

The constituent clans of the Dervish during the formative years belonged to sections of the Ogaden and Dhulbahante.[27] Habr Je'lo and Habr Yunis clans:

He acquired some notoriety by seditious preaching in Berbera in 1895, after which he returned to his tariga in Kob Faradod, in the Dolbahanta. Here he gradually acquired influence by stopping inter-tribal warfare, and eventually started a religious movement in which the Rer Ibrahim (Mukahil Ogaden), Ba Hawadle (Miyirwalal Ogaden) and the Ali Gheri (Dolbahanta) were the first to join. His emissaries also soon succeeded in winning over the Adan Madoba, notable amongst whom was Haji Sudi, his trusted lieutenant, and the Ahmed Farih and Rer Yusuf, all Habr Toljaala, and the Musa Ismail of the Eastern Habr Yunis, Habr Gerhajis, with Sultan Nur.[28]

Between 1900 and 1913, they operated from temporary local centers such as Aynabo in Somaliland and Illig in Puntland.[15] Neville Lyttelton's War Office, and General Egerton described the Nugaal as the "base of operations" against Dervishes.[29]

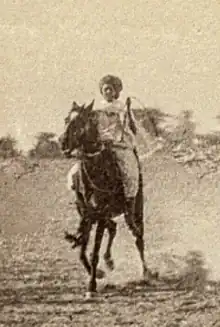

The Dervishes wore white turban and its army utilized horses for movement. They assassinated opposing clan leaders.[15] Dervish soldiers used the dhaanto and geeraar traditional dance-song to raise their esprit de corps and sometimes sang it on horseback.[30] Hasan commanded the Dervish movement soldiers in a martial manner, ensuring that they were religiously committed, powered up for warfare and men of character sworn with an oath of allegiance.[14] To ensure unity among his troops, instead of letting them identify themselves by their different tribes, he made them identify themselves uniformly as Dervish.[31] The movement obtained firearms from Sultan Boqor Osman Mahmud of Majerteen Sultanate, as well as the Ottoman Empire and Sudan. In addition, the Dervishes also obtained significant armaments' from the Adan Madoba section of the Habr Je'lo clan where, according to the contemporary source Official History of the Operations in Somaliland: "Of the former the Adan Madoba were not only responsible for supplying him Abdullah Hassan with arms, but also assisted him on all his raids."[32][23]

The Dervish fought many battles starting in 1899 against the Ethiopian troops.[14] In 1904, the Dervishes were almost annihilated in Jidbaley. Hasan retreated into the Italian Somaliland and entered into a treaty with them, who accepted the control of Eyl port by the Dervishes. This port served as the Dervish headquarters between 1905 and 1909.[15] During this period, Hasan rebuilt the Dervish movement army, the Dervishes raided and plundered their neighboring clans, and in 1909 assassinated their archrival Sufi leader Uways al-Barawi and burnt his settlement, according to Mohamed Mukhtar.[33]

In 1913, after the British withdrawal to the coast, the Dervishes created a walled town with fourteen fortresses in Taleh by importing masons from Yemen. This served as their headquarters.[34][35] The main fortress, Silsilat, included conical tower granaries that opened only at the top, wells with sulfurous water, cattle watering stations, a guard tower, walled garden, and tombs. It became the residence of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, his wives and family.[34] The Taleh structures also included the Hed Kaldig (literally, "place of blood"), where those whom Hasan disliked were executed with or without torture and their bodies left to the hyenas.[34] According to Muktar, Hasan's execution orders also targeted dozens of his former friends and allies.[33] The town of Taleh was mostly destroyed after a RAF aerial bombardment in early February 1920, though Hasan had already left his compound by then.[34][36] In an April 1920 letter transcribed from the original Arabic script into Italian by the incumbent Governatori della Somalia, the British are described taking twenty-seven garesas or 27 houses from the Dhulbahante clan.[37]

Relations with the Biimal

His letter to the Bimal was documented as the most extended exposition of his mind as a Muslim thinker and religious figure. The letter is until this day still preserved. It is said that the Bimal thanks to their size being numerically powerful, traditionally and religiously devoted fierce warriors and having possession of much resources have intrigued Mahamed Abdulle Hassan. But not only that the Bimal themselves mounted an extensive and major resistance against the Italians, especially in the first decade of the 19th century. The Italians carried many expeditions against the powerful Bimal to try and pacify them. Because of this the Bimal had all the reasons to join the Dervish struggle and by doing so to win their support over the Sayyid wrote a detailed theological statement to put forward to the Bimal tribe who dominated the strategic Banaadir port of Merca and its surroundings.[38]

One of the Italian's greatest fears was the spread of 'Dervishism' (had come to mean revolt) in the south and the strong Bimaal tribe of Benadir whom already were at war with the Italians, whom in this case were engaged in supplying arms to the Bimaal.[39] The Italians wanted to bring in an end to the Bimaal revolt and at all cost prevent a Bimal-Dervish alliance, which lead them to use the forces of Obbia as prevention.[39]

In southern Somalia, there was another resistance, the Bimal or Banadir Resistance. This was a large resistance lead by the Bimal clan spanning 3 decades of war. The Bimal being the main element, eventually neighboring adjacent tribes also joined the Bimal in their struggle against the Italians. The Italians feared that the Banadir Resistance would join hands with the Dervishes. During this period, is also when Dervish allies in Benadir had in 1909 assassinated their archrival Sufi leader Uways al-Barawi.[33]

The Dervish movement aimed to remove the British and Italian influence from the region and restore the "Islamic system of government with Islamic education as its foundation", according to Mohamed-Rahis Hasan and Salada Robleh.[6]

Engagements

In August 1899, the Dervish army occupied Burao, an important centre of British Somaliland, giving Muhammad Abdullah Hassan control over the city's watering places.[40] Hassan also succeeded in making peace between the local clans and initiated a large assembly, where the population was urged to join the war against the British. His forces were supplied with the simple uniforms consisting of "a white cotton outer garment (worn by most Somali men of the time anyway), a white turban, a tasbih (or rosary), and a rifle."[41]

In March 1900, Hassan along with his dervish forces attacked an Ethiopian outpost near Jijiga. Capt. Malcolm McNeill who commanded the Somali Field Force against Hassan reported that the Dervish were completely defeated, and that they have suffered a heavy loss amounting to 2,800 killed, according to the Ethiopians.[42] Similar raids by the dervish would continue despite the losses across the Somali peninsula until 1920. McNeill notes that by June 1900, Hassan made his position even stronger than before his March 1900 defeat and had “practically dominated the whole of the southern portion of our Protectorate”.[42]

The British administration started to coordinate with the Italians and Ethiopians, and by 1901 a joint Anglo-Ethiopian force began to coordinate plans to eradicate the jihadists or limit their reach farther west to the Ogaden or borderland of northern Kenya. Lack of supplies and access to fresh drinking water in the large expanse of flat land made this a challenging feat for the British and their allies. In contrast, Hassan and his dervishes adapted harsh conditions of the land by eating carcasses of beasts and drinking water from the dead bellies of animals.[42] Despite possessing superior weapons, including Maxim machine guns, until 1905, the Anglo-Ethiopian forces were still struggling to gain hold on the dervish movement.

Finally, the British Cabinet approved of air operations against the Dervish movement. It is said that the challenge of the Dervishes presented the British with a suitable environment to trial its new doctrine of warfare, which stressed "the use of aircraft as the primary arm, usually supplemented by ground forces, according to particular requirements."[43]

In the Somaliland campaign of 1920, 12 Airco DH.9A aircraft were used to support the British forces. Within a month, the British had occupied the capital of the Dervish State and Hassan had retreated to the west.[43]

Demise

Korahe raid

In the early 20th century during the Dervish wars, the British and Abyssinians came to an agreement that cross border camel raiding between the Somali tribes was to be banned and that the offending tribes would be punished by their respective governments. The Abyssinians only nominally having control over the Haud failed to meet their end of the agreement and this resulted in the Dervish and Ogaden alliance raiding with impunity while the Isaaq and Dhulbahante were unable to avenge the raids due to the British Camel Corps restraining them and returning looted Ogaden livestock. The secretary administrator of British Somaliland, Douglas James Jardine noted that the Isaaq sub clans inhabiting the Haud were in fact militarily superior and stronger than their Ogaden counterparts. After a series of Dervish-Ogaden raids, tribal elders held talks with the British Government, forcing the latter to lift the ban and let the clans deal with the Dervish-Ogaden themselves. The man chosen to lead the tribal forces was Akil (tribal chief) Haji Mohammad Bullaleh (also known as Haji Warabe) who himself had previous quarrels with the Mullah.[44][45]

After the bombing campaign of the Taleh fort the Dervish retreated in to the Ogaden territory in Abyssinia and the Mullah was able to attract followers from his tribe. The catalyst for the Hagoogane raid happened on May 20, 1920, when a Dervish-Ogaden force raided the Ba Hawadle sub clan of the Ogaden who were under the protection of the Isaaq, killing women and children in the process.

Haji Warabe assembled an army composed of 3000 Habr Yunis, Habr Je'lo and Dhulbahante warriors. The army set out from Togdheer, on the dawn of July 20, 1920, Haji's army reached Korahe just west of Shineleh where the Dervish and their tribal allies were camped and commenced to attack with them with force. The Dervish-Ogaden numbering 800 were defeated swiftly and only a 100 survived the onslaught and fled south. Haji and his army looted 60,000 livestock and 700 rifles from their defeated foes. During the midst of the battle Haji Warabe entered the Mullah's tent to face his adversary but found the tent empty with the Mullah's tea still hot.[46] The Mullah had fled to Imi where he would die due to influenza shortly afterwards. Haji Warabe's Habr Yunis and Habr Je'lo warriors divided the livestock and rifles amongst themselves denying the Dhulbahante soldiers their share as mentioned by Salaan Carrabey in his Guba poem addressed to Ali Dhuh.[47] The looting dealt a severe blow to them economically, a blow from which they did not recover.[48][49][50][51]

Religion

The Dervishes had a local religious strand that of the religious teacher Kudquran,[52] and that derived from a Sudanese preacher, the sect Salahiyya,[53] was according to an 1899 letter by James Hayes Sadler established 12 years prior, thus in 1887.[54] In their specific sect, they taught life sobriety and abstemiousness and teetotalism and nephalism pertaining to mind-altering substances.[54] This sect was espoused until 1910 when its founder in Mecca denounced the Dervish via a letter.[53] Nonetheless, some authors trivialized the role of religion: out of the twenty-seven forts built by the Dervish, not a single one of them had a mosque constructed within them, which according to one colonial official placed doubt that there was a religious impulse behind Dervish statehood.[55] The general consul of the Somali Coast Protectorate based in Berbera downplayed the role of antagonism to Christian missionaries to the Dervish that "originated in the Dolbahanta":[56]

I do not consider that the presence of this Mission in Berbera has had anything to do with the movement that originated in the Dolbahanta

— Consul general

Douglas Jardine likewise deemphasized a religious role, rather attributing Dervish motives to "avarice" and them considering tribal confrontations as a "national sport".[57] Hasan left the urban settlement and moved to preach in the countryside. His influence spread in the rural parts and many elders, as well as youth, became his followers. Hasan converted the influenced youth from different clans into a Muslim brotherhood,[21] rallying to protect Islam from the influence of the Christian missionaries.[58] Hassan stated the "British infidels have destroyed our [Islamic] religion and made our children their children".[23] These formed the Hasan's armed resistance group to confront the colonial powers, and came to be known as Dervishes or Daraawiish, states Said M. Mohamed.[4]

Legacy

According to the Somali historian and novelist Farah Awl the Sayyid had a significant influence on Sheikh Bashir through listening to his poetry and conversations, an influence that impelled him to a "war with the British". After studying in the markaz in Beer he opened a Sufi tariqa (order) sometime in the 1930s, where he preached his ideology of anti-imperialism, stressing the evil of colonial rule and the bringing of radical change through war. His ideology was shaped by a millennial bent, which according to Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm is the "hope of a complete and radical change in the world shorn of all its present deficiencies".[59] The Dervish movement would subsequently inspire Sheikh Bashir, the nephew of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan who was named by him, to wage his own 1945 Sheikh Bashir Rebellion together with Habr Je'lo tribesmen against the British authorities in Somaliland.[60][61]

The Dervish legacy in Somalia and Somaliland has been influential. It was the "most important revivalist Islamic movements" in Somalia, state Hasan and Robleh.[62] The movement and particularly its leader has been controversial among Somalis. Some cherish it as the founder of modern Somali nationalism, while some others view it as an ambitious Muslim brotherhood militancy that destroyed Somalia's opportunity to move towards modernization and progress in favor of a puritanical Islamic state embedded with Islamic education – ideas enshrined in the contemporary constitution of Somalia.[62] Yet others such as Aidid consider the Dervish legacy was one of cruelty and violence against those Somalis who disagreed with or refused to submit to Hasan. These Somalis were "declared infidels" and Dervish soldiers were ordered by Hasan to "kill them, their children and women and snatch all their property", according to Shultz and Dew.[14][63] Another legacy that came out of the prolonged struggle and violence between the colonial powers and the Dervish movement, according to Abdullah A. Mohamoud, was the arming of the Somali clans followed by decades of destructive clan-driven militarism, violent turmoil, and high human costs well after the demise of the Dervish movement.[64][65]

Hasan and his Dervish movement have inspired a nationalistic following in contemporary Somalia.[66][67] The military government of Somalia led by Mohamed Siad Barre, for example, erected statues visible between Makka Al Mukarama and Shabelle Roads in the heart of Mogadishu. These were for three major Somali History icons: Mohammed Abdullah Hassan of the Dervish movement, Stone Thrower and Hawo Tako. The Dervish period spawned many war poets and peace poets involved in a struggle known as the Literary war which had a profound effect on Somali poetry and Literature, with Mohammed Abdullah Hassan featuring as the most prominent poet of that Age.[68] The flag of Khatumo, designed by Rooda Xassan features a Dervish cavalryman.[69]

| History of Somalia |

|---|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) |

|

|

| History of Somaliland |

|---|

|

|

|

See also

Notes

- The term Dervish, states Abdullah A. Mohamoud citing Beachey, has origins in the Turkish dervi or Persian darvesh. It means "ardent fighters for Islam" with an austere lifestyle.[9]

References

- Mengisteab, Kidane; Bereketeab, Redie (2012). Regional Integration, Identity & Citizenship in the Greater Horn of Africa. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-84701-058-2.

- Hoehne, Markus V. (2016), "Dervish State (Somali)", The Encyclopedia of Empire, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–2, doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe069, ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4, retrieved 22 February 2022

- Meehan, Erin Elizabeth (2021). Dervish Oral Poetry in Somalia: A Study in Semiotic Chora. Salve Regina University. p. 2.

- Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong; Mr. Steven J. Niven (2012). Dictionary of African Biography. Oxford University Press. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. pp. 60–61, 70–72 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- Hasan, Mohamed-Rashid S., and Salada M. Robleh (2004), "Islamic revival and education in Somalia", Educational Strategies Among Muslims in the Context of Globalization: Some National Case Studies, Volume 3, BRILL Academic, page 147

- Mukhtar, Mohamed (2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 27.

- Abdi Ismail Samatar (1989). The State and Rural Transformation in Northern Somalia, 1884-1986. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-299-11994-2.

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. p. 71 with footnote 81. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- Smtar, Ahmed (1988). Socialist Somalia: Rhetoric and Reality. Zed Books. p. 32.

the allocation of part of the Nugaal valley - in between the British and Italian Somalilands – to Dervish rule

- Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-Clio. p. 78.

- Nelson, Harold (1982). Somalia, a Country Study. Library of Congress. p. 18.

but in 1905 the British accepted Italian mediation in arranging a truce that conferred on the imam an Italian subsidy and autonomous protected status in the Nugaal (Nogal) Valley. Mohamed Abdullah did not gain extensive support in Italian Somaliland, although some clans there declared themselves dervishes and robbed cattle from the herds of other Somalis who were deemed to accommodating to the Italians

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (2003). Historical dictionary of Somalia. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1. OCLC 268778107.

- Richard H. Shultz; Andrea J. Dew (2009). Insurgents, Terrorists, and Militias: The Warriors of Contemporary Combat. Columbia University Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-231-12983-1.

- Markus V. Hoehne (2016). John M Mackenzie (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Empire. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe069. ISBN 978-11184-406-43.

- Michel Ben Arrous; Lazare Ki-Zerbo (2009). African Studies in Geography from Below. African Books. p. 166. ISBN 978-2-86978-231-0.

- Robert L. Hess (1964). "The 'Mad Mullah' and Northern Somalia". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 5 (3): 415–433. doi:10.1017/S0021853700005107. JSTOR 179976. S2CID 162991126.

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960–2001). Purdue University Press. pp. 60–61, 70–72 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- Abdi Abdulqadir Sheik-'Abdi (1993). Divine madness : Mohammed 'Abdulle Hassan (1856-1920). Atlantic Highlands, N.J. p. 69. ISBN 0862324432.

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. pp. 70 with footnote 79. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- Sayyid Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan, Encyclopedia Britannica

- David Motadel (2014). Islam and the European Empires. Oxford University Press. pp. 17–18 with footnotes 49–50, 165–166. ISBN 978-0-19-966831-1.

- Raphael Chijioke Njoku (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-313-37857-7.

- Benjamin Hopkins (2014). David Motadel (ed.). Islam and the European Empires. Oxford University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-19-966831-1., Quote: "Men of religious learning and authority were well-positioned in these societies [Somaliland, Sudan, Northwest Frontier of British India] to straddle the disparate and often conflicting interests of local peoples. The protection of Islam became their rallying cry, providing a coherent narrative of and justification for resistance against the forces of colonialism, as well as a unifying force which superseded particularist tribal identities."

- Robert L. Hess (1968). Norman Robert Bennett (ed.). Leadership in Eastern Africa: Six Political Biographies. Boston University Press. p. 103.

- R. W. Beachey (1990). The warrior mullah: the Horn aflame, 1892-1920. Bellew. pp. 37–44. ISBN 978-0-947792-43-5.

-

- Abdi, Abdulqadir (1993). Divine Madness. Zed Books. p. 101.

to the Dervish cause, such as the Ali Gheri, the Mullah's maternal kinsmen and his first converts. In fact, Swayne had instructions to fine the Ali Gheri 1000 camels for possible use in the upcoming campaign

*Bartram, R (1903). The annihilation of Colonel Plunkett's force. The Marion Star.By his marriage he extended his influence from Abyssinia, on the west, to the borders of Italian Somaliland, on the east. The Ali Gheri were his first followers.

*Hamilton, Angus (1911). Field Force. Hutchinson & Co. p. 50.it appeared for the nonce as if he were content with the homage paid to his learnings and devotional sincerity by the Ogaden and Dolbahanta tribes. The Ali Gheri were his first followers

*Leys, Thomson (1903). The British Sphere. Auckland Star. p. 5.Ali Gheri were his first followers, while these were presently joined by two sections of the Ogaden

- Abdi, Abdulqadir (1993). Divine Madness. Zed Books. p. 101.

- Official History of the Operations in Somaliland, 1901-04. H. M. Stationery office. p. 49.

- War Office, British (1907). Official History of the Operations in Somaliland, 1901-04. p. 315.

situated in every way for a base of operations in the Nogal which it was evident must form the theatre of war

- Johnson, John William (1996). Heelloy: Modern Poetry and Songs of the Somali. Indiana University Press. p. 31. ISBN 1874209812.

- Saadia Touval (1963). Somali nationalism: international politics and the drive for unity in the Horn of Africa. Harvard University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780674818255.

- Official History of the Operations in Somaliland, 1901-04. H. M. Stationery office. p. 41.

- Mohamed Haji Mukhtar (2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- W. A. MacFadyen (1931), Taleh, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 125–128

- Robert L. Hess (1968). Norman Robert Bennett (ed.). Leadership in Eastern Africa: Six Political Biographies. Boston University Press. pp. 90–97.

- Michael Napier (2018). The Royal Air Force: A Centenary of Operations. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-4728-2539-1.

- Ferro e Fuoco in Somalia, da Francesco Saverio Caroselli, Rome, 1931; p. 272. "i Dulbohanta nella maggior parte si sono arresi agli inglesi e han loro consegnato ventisette garese (case) ricolme di fucili, munizioni e danaro." (English: "the Dhulbahante surrendered for the most part to the British and handed twenty-seven garesas (houses) full of guns, ammunition and money over to them."viewable link

- Samatar, Said S. (1992). In the Shadow of Conquest: Islam in Colonial Northeast Africa. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-0-932415-70-7.

- Hess, Robert L. (1 January 1964). "The 'Mad Mullah' and Northern Somalia". The Journal of African History. 5 (3): 415–433, page 422. doi:10.1017/s0021853700005107. JSTOR 179976. S2CID 162991126.

- Teutsch, Friederike (1999). Collapsing Expectation: National Identity and Disintegration of the State of Somalia. Centre of African Studies, Edinburgh University. p. 33.

- Martin, B. G. (13 February 2003). Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521534512.

- Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313378577.

- Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313378577.

- The Mad Mullah Of Somaliland, Douglas Jardine, pp. 306

- Personal and Historical Memoirs of an East Africa Administrator pp.112-113

- Beachey, R. W. (1990). The warrior mullah: the Horn aflame, 1892-1920, by R.W Beachey, p.153. ISBN 9780947792435.

- A Somali Poetic Combat Pt. I, II and III. pp.43

- Irons, Roy (4 November 2013). Churchill and the Mad Mullah of Somaliland, p. 209. ISBN 9781783463800.

- Nicolosi, Gerardo (2002). Imperialismo e resistenza in corno d'Africa: Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, P.305. ISBN 9788849803846.

- "King's College London, King's collection: Ismay's summary as Intelligence Officer (1916-1918) of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan".

- Beachey, R. W. (1990). The warrior mullah: the Horn aflame, 1892-1920, by R.W Beachey, p.153. ISBN 9780947792435.

- Ciise, Jaamac (1976). Taariikhdii daraawiishta iyo Sayid Maxamad Cabdille Xasan. p. 175.

largest and most important division, probably looked upon as the reserve composed of Ba-Ararsama, Aligheri, Kayad, Mahomed Gerad and many Hassan Agaz

- Douglas Jardine, 1923 "the Sheikh despatched a denunciatory letter to the Mullah, reproaching him in no measured terms and pointing out that conduct was not only at variance with the tenets of the sect"

- of Commons, House (1901). Sessional Papers. p. 1.

This sect was established in Berbera about twelve years ago. It preaches more regularity in the hour of prayer, stricter attention to the forms of religion, and the interdiction of Kat — a leaf the Arabs and coast Somalis are much addicted to chewing on account of its strengthening ... This teaching has not found much favour with the people of the town.

- The National Archives UK - CO 1069-8-64

- Omar Issa, Jama (2005). Taariikhdii daraawiishta iyo Sayid Maxamad Cabdille Xasan 1895-1920. p. 45.

I do not consider that the presence of this Mission in Berbera has had anything to do with the movement that originated in the Dolbahanta, though it is doubtless a useful level with which to try and raise disaffection amongst ... I am a Hashimi by descent, Shaffei by doctrine, a Sunni and belonging to the Ahmedieh tarika. This is for my part

- Douglas Jardine, 1923, p. 50 "So few were the followers whom religion or politics attracted to the Mullah's standard, that we must look elsewhere for the motive which inspired the majority of his following; and we find it in the cardinal sin of the Somali, avarice. Inter-tribal fighting and raiding constitute the Somali's national sport"

- Benjamin Hopkins (2014). David Motadel (ed.). Islam and the European Empires. Oxford University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-19-966831-1., Quote: "Men of religious learning and authority were well-positioned in these societies [Somaliland, Sudan, Northwest Frontier of British India] to straddle the disparate and often conflicting interests of local peoples. The protection of Islam became their rallying cry, providing a coherent narrative of and justification for resistance against the forces of colonialism, as well as a unifying force which superseded particularist tribal identities."

- Hobsbawm, Eric (1 June 2017). Primitive Rebels. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-349-14300-2.

- Jama Mohamed, ‘The Evils of Locust Bait’: Popular Nationalism During the 1945 Anti‐Locust Control Rebellion in Colonial Somaliland, Past & Present, Volume 174, Issue 1, February 2002, Pages 201–202

- of Rodd, Lord Rennell (1948). British Military Administration in Africa 1941-1947. HMSO. p. 481.

- Hasan, Mohamed-Rashid S., and Salada M. Robleh (2004), "Islamic revival and education in Somalia", Educational Strategies Among Muslims in the Context of Globalization: Some National Case Studies, Volume 3, BRILL Academic, pages 143, 146-148, 150-152

- Kimberly A. Huisman (2011). Kimberly A. Huisman; Mazie Hough; et al. (eds.). Somalis in Maine: Crossing Cultural Currents. North Atlantic Books. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-55643-926-1.

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. pp. 60–61, 70–72 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- Rebecca Richards (2016). Understanding Statebuilding: Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland. Routledge. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-317-00466-0.

- Lotje de Vries; Pierre Englebert; Mareike Schomerus (2018). Secessionism in African Politics: Aspiration, Grievance, Performance, Disenchantment. Springer International. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-3-319-90206-7.

- Said S. Samatar (1982). Oral Poetry and Somali Nationalism: The Case of Sayid Mahammad 'Abdille Hasan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 20–24, 72–73. ISBN 978-0-521-23833-5.

- SOMALIA: A Nation's Literary Death Tops Its Political Demise by Said S Samatar

- "Calanka Khaatumo: Ha dhicin oo ha dheeliyin". 11 January 2013.