Military history of Somalia

The military history of Somalia encompasses the major conventional wars, conflicts and skirmishes involving the historic empires, kingdoms and sultanates in the territory of present-day Somalia, through to modern times. It also covers the martial traditions, military architecture and hardware employed by Somali armies and their opponents.

In the early Middle Ages, the Ajuran Empire expanded its territories and established its hegemonic rule through a skillful combination of warfare, trade linkages and alliances,[1] and defeated the Portuguese many times in the Indian Ocean. The Kingdom of Ifat successfully conquered the Kingdom of Shewa in the same time-period. A hundred years later a major conventional war would commence during the Conquest of Abyssinia pitching the Kingdom of Adal allied by the Ottoman Empire against the Solomonic Dynasty supported by the Portuguese Empire. The conflict is the earliest example of cannon and matchlock warfare on the continent.

The early modern period saw the rise and fall of the Gobroon Dynasty, a southern military power that successfully subdued the Bardera militant's and forced the Omanis to pay tribute. This period also saw an increased focus by Global Empires on colonial expansion. The three major imperial powers of Britain, Italy and France consequently sought and signed various protectorate treaties with the ruling Somali Sultans, such as Mohamoud Ali Shire of the Warsangali Sultanate, Osman Mahamuud of the Majeerteen Sultanate and Yusuf Ali Kenadid of the Sultanate of Hobyo. Supplied with military hardware by the European powers, the Ethiopian Empire also sought to expand its own influence in the Horn region. These competing influences gave birth to the Dervish State, a polity wherein the monarch was Diiriye Guure, whilst its emir was Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan ("The Mad Mullah"). The Dervish forces successfully repulsed the British Empire in four military expeditions and forced it to retreat to the coastal region, remaining independent throughout World War I.[2] After a quarter of a century of holding the British at bay, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920, when Britain for the first time in Africa used airplanes to bomb the Dhulbahante garesas[3] at the Dervish capital of Taleh, Somaliland.[4]

World War II saw many Somali men join Italian forces during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War and during the East African Campaign; and later also British forces in the Pacific War. After independence, the Somali Republic adopted an irredentist foreign policy with the intention to reconstruct the pre-WW2 borders (of Somalia Governorate) and establish an all-encompassing Greater Somalia. This culminated in several conventional wars and border skirmishes in the form of the 1964 Border War, the Shifta War, the Ogaden War, the Rhamu Incident, and the 1982 Border war, which pitched the Somali military against other forces. The fallout from these various conflicts also forged new partnerships. By the end of the 1980s, Somalia's initial friendship with the Soviet Union and subsequent partnership with the United States enabled it to build the largest army on the continent.[5] The armed forces largely disbanded with the onset of the civil war in the early 1990s, but were later gradually reconstituted in the 2000s (decade) with the establishment of the Transitional Federal Government.

Ancient and Medieval

| History of Somalia |

|---|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) |

|

|

Ancient Somalia

In the northern Dhambalin region of Somalia, a depiction of a man on a horse is postulated as being one of the earliest known examples of a mounted huntsman.[6] A 17th-century BC text found in a tomb in El Kab, belonging to the local governor, Sobeknakht II, mentions “a huge attack from the south on El Kab and Ancient Egypt by the Kingdom of Kush and its allies from the Land of Punt”.[7][8] In ancient times Somalia was known to the Chinese as the "country of Pi-pa-lo", which had four departmental cities each trying to gain the supremacy over the other. It had twenty thousand troops between them, who wore cuirasses, a protective body armor.[9]

Ifat-Solomonic Wars

In the early Middle Ages, the Muslim and Christian kingdoms of modern Somalia and Ethiopia enjoyed friendly relations for centuries. The conquest of Shewa by the Ifat Sultanate ignited a rivalry for supremacy between the Christian Solomonids and the Muslim Ifatites which resulted in several devastating wars. After the wars, the reigning king had his minstrels compose a song praising his victory, which contains the first written record of the word "Somali". Sa'ad ad-Din II's family was subsequently given safe haven at the court of the King of Yemen, where his sons regrouped and planned their revenge on the Solomonids.

The oldest son Sabr ad-Din II build a new capital eastwards of Zeila known as Dakkar and began referring to himself as the King of Adal. He continued the war against the Solomonic Empire. Despite his army's smaller size, he was able to defeat the Solomonids at the battles of Serjan and Zikr Amhara and consequently pillaged the surrounding areas. Many similar battles were fought between the Adalites and the Solomonids with both sides achieving victory and suffering defeat but ultimately Sultan Sabr ad-Din II successfully managed to drive the Solomonic army out of Adal territory. He died a natural death and was succeeded by his brother Mansur ad-Din who invaded the capital and royal seat of the Solomonic Empire and drove Emperor Dawit II to Yedaya where according to al-Maqrizi, Sultan Mansur destroyed a Solomonic army and killed the Emperor. He then advanced to the mountains of Mokha where he encountered a 30 000 strong Solomonic army. The Adalite soldiers surrounded their enemies and for two months besieged the trapped Solomonic soldiers until a truce was declared in Mansur's favour.

Later on in the campaign, the Adalites were struck by a catastrophe when Sultan Mansur and his brother Muhammad were captured in battle by the Solomonids. Mansur was immediately succeeded by the youngest brother of the family Jamal ad-Din II. Sultan Jamal reorganized the army into a formidable force and defeated the Solomonic armies at Bale, Yedeya and Jazja. Emperor Yeshaq responded by gathering a large army and invaded the cities of Yedeya and Jazja but was repulsed by the soldiers of Jamal. Following this success, Jamal organized another successful attack against the Solomonic forces and inflicted heavy casualties in what was reportedly the largest Adalite army ever fielded. As a result, Yeshaq was forced to withdraw towards the Blue Nile over the next five months, while Jamal ad Din's forces pursued them and looted much gold on the way, although no engagement ensued.

After returning home, Jamal sent his brother Ahmad with the Christian battle-expert Harb Jaush to successfully attack the province of Dawaro. Despite his losses, Emperor Yeshaq was still able to continue field armies against Jamal. Sultan Jamal continued to advance further into the Abyssinian heartland. However Jamal upon hearing of Yeshaq's plan to send several large armies to attack three different areas of Adal, including the capital returned to Adal where he fought the Solomonic forces at Harjai and according to al-Maqrizi this is where the Emperor Yeshaq died in battle. The young Sultan Jamal ad-Din II at the end of his reign had outperformed his brothers and forefathers in the war arena and became the most successful ruler of Adal to date. Within a few years, however, Jamal was assassinated by either disloyal friends or cousins around 1432 or 1433, and was succeeded by his brother Badlay ibn Sa'ad ad-Din. Sultan Badlay continued the campaigns of his younger brother and began several successful expeditions against the Christian empire. He recovered the Kingdom of Bali and began preparations of a major Adalite offensive into the Ethiopian Highlands. He successfully collected funding from surrounding Muslim Kingdoms as far away as the Sultanate of Mogadishu.[10] These ambitious plans however were thrown out the war chamber when King Badlay died during the invasion of Dawaro. He was succeeded by his son Muhammad ibn Badlay who sent envoys to the Sultan of Mamluk Egypt to gather support and arms in the continuing war against the Christian empire. The Adalite ruler Muhammad and the Solomonic ruler Baeda Maryam agreed to a truce and both states in the following decades saw an unprecedent period of peace and stability.

Ethiopian Involvement

Sultan Muhammad was succeeded by his son Shams ad Din while Emperor Baeda Maryam was succeeded by his son Eskender. During this time period warfare broke out again between the two states and Emperor Eskender invaded Dakkar where he was stopped by a large Adalite army who destroyed the Solomonic army to such an extent that no further expeditions were carried out for the remaining of Eskender's reign. Adal however continued to raid the Christian empire unabated under the General Mahfuz, the leader of the Adalite war machine who annually invaded the Christian territories. Eskender was succeeded by Emperor Na'od who tried to defend the Christians from General Mahfuz but he too was also killed in battle by the Adalite army in Ifat.

At the turn of the 15th to 16th centuries, Adal regrouped and around 1527 under the charismatic leadership of Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (Gurey in Somali, Gragn in Amharic, both meaning "left-handed), Adal invaded Ethiopia. Adalite armies with Ottoman support and arms marched into Ethiopia and caused considerable damage to the Highland state. Many historic Churches, manuscripts and settlements were looted and burned during the campaigns.[12] Adal's use of firearms, still only rarely used in Ethiopia, allowed the conquest of well over half of Ethiopia, reaching as far north as Tigray. The complete conquest of Ethiopia was averted by the timely arrival of a Portuguese expedition led by Cristovão da Gama, son of the famed navigator Vasco da Gama.[13] The Portuguese had been in the area earlier in early 16th centuries (in search of the legendary priest-king Prester John), and although a diplomatic mission from Portugal, led by Rodrigo de Lima, had failed to improve relations between the countries, they responded to the Ethiopian pleas for help and sent a military expedition to their fellow Christians. A Portuguese fleet under the command of Estêvão da Gama was sent from India and arrived at Massawa in February 1541. Here he received an ambassador from the Emperor beseeching him to send help against the Muslims, and in July following a force of 400 musketeers, under the command of Christovão da Gama, younger brother of the admiral, marched into the interior, and being joined by Ethiopian troops they were at first successful against the Muslims but they were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Wofla (28 August 1542), and their commander captured and executed. On February 21, 1543, however, a joint Portuguese-Ethiopian force defeated the Muslim army at the Battle of Wayna Daga, in which Ahmed Gurey was killed. Ahmed Gurey's widow married his nephew Nur ibn Mujahid, in return for his promise to avenge Ahmed's death, who succeeded Ahmed Gurey, and continued hostilities against his northern adversaries until he killed the Ethiopian Emperor in his second invasion of Ethiopia.

Ajuran-Portuguese wars

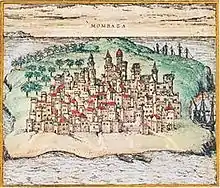

The European Age of discovery brought Europe's then superpower the Portuguese empire to the coast of East Africa, which enjoyed a flourishing trade with foreign nations. The wealthy southeastern city-states of Kilwa, Mombasa, Malindi, Pate and Lamu were all systematically sacked and plundered by the Portuguese. Tristão da Cunha then set his eyes on Ajuran territory, where the battle of Barawa was fought. After a long period of engagement, the Portuguese soldiers burned the city and looted it. Fierce resistance by the local populace and soldiers resulted in the failure of the Portuguese to permanently occupy the city, and the inhabitants who had fled to the interior eventually returned and rebuild the city. After Barawa, Tristão set sail for Mogadishu, the richest city on the East African coast at the time. Word had spread of what had happened in Barawa, and a large troop mobilization took place. Many horsemen, soldiers and battleships in defense positions were guarding the city. Nevertheless, Tristão opted to storm and attempt to conquer the city, although every officer and soldier in his army opposed this, fearing certain defeat if they were to engage their opponents in battle. Tristão heeded their advice and sailed for Socotra instead.[15] After the battle the city of Barawa quickly recovered from the attack.[16]

In 1542, the Portuguese commander João de Sepúvelda led a small fleet on an expedition to the Somali coast. During this expedition he briefly attacked Mogadishu, capturing an Ottoman ship and firing upon the city, which compelled the sultan of Mogadishu to sign a peace treaty with the Portuguese.[17]

Over the next several decades Somali-Portuguese tensions remained high and the increased contact between Somali sailors and Ottoman corsairs worried the Portuguese who sent a punitive expedition against Mogadishu under João de Sepúlveda, which was unsuccessful.[19] Ottoman-Somali cooperation against the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean reached a high point in the 1580s when Ajuran clients of the Somali coastal cities began to sympathize with the Arabs and Swahilis under Portuguese rule and sent an envoy to the Turkish corsair Mir Ali Bey for a joint expedition against the Portuguese. He agreed and was joined by a Somali fleet, which began attacking Portuguese colonies in Southeast Africa.[20]

The Somali-Ottoman offensive managed to drive out the Portuguese from several important cities such as Pate, Mombasa and Kilwa. However, the Portuguese governor sent envoys to Portuguese India requesting a large Portuguese fleet. This request was answered and it reversed the previous offensive of the Muslims into one of defense. The Portuguese armada managed to re-take most of the lost cities and began punishing their leaders, but they refrained from attacking Mogadishu, securing the city's autonomy in the Indian Ocean.[21][22] The Ottoman Empire would remain an economic partner of the Somalis.[23] Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries successive Somali Sultans defied the Portuguese economic monopoly in the Indian Ocean by employing a new coinage which followed the Ottoman pattern, thus proclaiming an attitude of economic independence in regard to the Portuguese.[24]

Early modern

Gobroon-Bardera War

In the early modern period the Gobroon Dynasty, a Somali royal house ruled parts of Horn of Africa as a regional power during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was established by the Ajuran soldier Ibrahim Adeer, who had defeated various vassals of the collapsed Ajuran Empire and established the House of Gobroon. The dynasty reached its apex under the successive reigns of Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, who successfully consolidated Gobroon power during the Bardera wars, and Sultan Ahmed Yusuf, who was considered to be the most powerful king in east Africa in his time. He managed to gather 20 thousand brave & strong Somali troops and invaded the Zanzibar island near Tanzania and he captured the Islands, slaughtered all the Arabic troops and freed the Bantu slaves and through his military dominance, Sultan Yusuf managed to exact tribute from the Omani king in the coastal town of Lamu.[25]

The Gobroon army numbered 20,000 men in times of peace, and could be raised to 50,000 troops in times of war.[26] The supreme commanders of the army were the Sultan and his brother, who in turn had Malaakhs and Garads under them. The military was supplied with rifles and cannons by Somali traders of the coastal regions that controlled the East African arms trade.

Darawiish Wars

At the end of the 19th century, the Berlin conference gathered together Europe's most powerful countries who decided amongst themselves the fate of the African continent. The British, Italians and Ethiopians partitioned Greater Somalia into spheres of influence, cutting into the previous nomadic grazing system and Somali civilizational network that connected port cities with those of the interior. The Ethiopian Emperor Menelik's Somali expedition, consisting of an army of 11,000 men, made a deep push into the vicinity of Luuq in Somalia. However, his troops were soundly defeated by the Gobroon army, with only 200 soldiers returning alive. The Ethiopians subsequently refrained from further expeditions into the interior of Somalia, but continued to oppress the people in the Ogaden by plundering the nomads of their livestock numbering in the hundreds of thousands. The British blockade in firearms to the Somalis rendered the nomads in the Ogaden helpless against the armies of Menelik. With the establishment of important Muslim orders headed by Somali scholars such as Shaykh Abd Al-Rahman bin Ahmad al-Zayla'i and Uways al-Barawi, a rebirth of Islam in East Africa was soon afoot. The resistance against the colonization of Muslim lands in Africa and Asia by the Afghans and Mahdists would inspire a large resistance movement in Somalia. Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, a former nomad boy that had traveled to many Muslim centers in the Islamic world, returned to Somalia as a grown man and began promoting the Salihiya order in the urban cities and the interior where he found major success.

The dervish entity created in 1895 consisted of a haroun (i.e. Darawiish government), the Darawiish king Diiriye Guure and its emir Sayid Mohamed, carved out a powerful state which was subdivided into 13 administrative divisions of which the four largest, Shiikhyaale, Dooxato, Golaweyne, Miinanle were near exclusively Dhulbahante. The other administrative divisions, Taargooye, Dharbash, Indhabadan, Burcadde-Godwein, Garbo (Darawiish), Ragxun, Gaarhaye, Bah-udgoon and Shacni-cali were collectively also overwhelmingly Dhulbahante.[27] The Dervish forces successfully repulsed the British Empire in four military expeditions, and forced it to retreat to the coastal region.[2] The Dervish State was recognized as an ally by the Ottoman Empire and the German Empire.[28][29] It also succeeded at outliving the Scramble for Africa, and remained throughout World War I the only independent Muslim power on the continent. After a quarter of a century of holding the British at bay, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920, when Britain for the first time in Africa used airplanes to bomb the Dhulbahante garesas at the Dervish capital of Taleh.

Italo - Somali War: Campaign of the Sultanates

In 1920, the Dervish state collapsed after intensive British aerial bombardments, and Dervish territories were subsequently turned into a protectorate. The dawn of fascism in the early 1920s heralded a change of strategy for Italy, as the north-eastern sultanates were soon to be forced within the boundaries of La Grande Somalia according to the plan of Fascist Italy. Prominent Somali royal houses at the time were the Majeerteen Sultanate ruled by King Osman Mahamuud, which controlled much of northeast and central Somalia; the Warsangali Sultanate ruled by Sultan Mahmoud Ali Shire; and the Sultanate of Hobyo ruled by Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi on 15 December 1923, things began to change for that part of the Somali territories. Italy had access to these areas under the successive protection treaties, but not direct rule. The Fascist government had direct rule only over the Benadir territory. Given the defeat of the Dervish movement in the early 1920s and the rise of fascism in Europe, on 10 July 1925 Mussolini gave the green light to De Vecchi to start the takeover of the north-eastern sultanates. Everything was to be changed and the treaties abrogated.

Governor De Vecchi's first plan was to disarm the sultanates. But before the plan could be carried out there should be sufficient Italian troops in both sultanates. To make the enforcement of his plan more viable, he began to reconstitute the old Somali police corps, the Corpo Zaptié, as a colonial force. In preparation for the plan of invasion of the sultanates, the Alula Commissioner, E. Coronaro received orders in April 1924 to carry out a reconnaissance on the territories targeted for invasion. In spite of the forty year Italian relationship with the sultanates, Italy did not have adequate knowledge of the geography. During this time, the Stefanini-Puccioni geological survey was scheduled to take place, so it was a good opportunity for the expedition of Coronaro to join with this.

Coronaro's survey concluded that the Ismaan Sultanate depended on sea traffic, therefore, if this were blocked any resistance which could be mounted came after the invasion of the sultanate would be minimal. As the first stage of the invasion plan Governor De Vecchi ordered the two Sultanates to disarm. The reaction of both sultanates was to object, as they felt the policy was in breach of the protectorate agreements. The pressure engendered by the new development forced the two rival sultanates to settle their differences over Nugaal possession, and form a united front against their common enemy.

The Sultanate of Hobyo was different from that of Majeerteen in terms of its geography and the pattern of the territory. It was founded by Yusuf Ali Keenadid in the middle of the 19th century in central Somalia. Its jurisdiction stretched from Ceeldheer through to Dusamareeb in the south-west, from Galladi to Galkacyo in the west, from Jerriiban to Garaad in the north-east, and the Indian Ocean in the east.

By 1 October, De Vecchi's plan was to go into action. The operation to invade Hobyo started in October 1925. Columns of the new Zaptié began to move towards the sultanate. Hobyo, Ceelbuur, Galkayo, and the territory between were completely overrun within a month. Hobyo was transformed from a sultanate into an administrative region. Sultan Yusuf Ali surrendered. Nevertheless, soon suspicions were aroused as Trivulzio, the Hobyo commissioner, reported movement of armed men towards the borders of the sultanate before the takeover and after. Before the Italians could concentrate on the Majeerteen, they were diverted by new setbacks. On 9 November, the Italian fear was realized when a mutiny, led by one of the military chiefs of Sultan Ali Yusuf, Omar Samatar, recaptured El-Buur. Soon the rebellion expanded to the local population. The region went into revolt as El-Dheere also came under the control of Omar Samatar. The Italian forces tried to recapture El-Buur but they were repulsed. On 15 November the Italians retreated to Bud Bud and on the way they were ambushed and suffered heavy casualties.

While a third attempt was in the last stages of preparation, the operation commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Splendorelli, was ambushed between Bud Bud and Buula Barde. He and some of his staff were killed. As a consequence of the death of the commander of the operations and the effect of two failed operations intended to overcome the El-Buur mutiny, the spirit of Italian troops began to wane. The Governor took the situation seriously, and to prevent any more failure he requested two battalions from Eritrea to reinforce his troops, and assumed lead of the operations. Meanwhile, the rebellion was gaining sympathy across the country, and as far afield as Western Somalia.

The fascist government was surprised by the setback in Hobyo. The whole policy of conquest was collapsing under its nose. The El-Buur episode drastically changed the strategy of Italy as it revived memories of the Adwa fiasco when Italy had been defeated by Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Furthermore, in the Colonial Ministry in Rome, senior officials distrusted the Governor's ability to deal with the matter. Rome instructed De Vecchi that he was to receive the reinforcement from Eritrea, but that the commander of the two battalions was to temporarily assume the military command of the operations and De Vecchi was to stay in Mogadishu and confine himself to other colonial matters. In the case of any military development, the military commander was to report directly to the Chief of Staff in Rome.

While the situation remained perplexing, De Vecchi moved the deposed sultan to Mogadishu. Fascist Italy was poised to re-conquer the sultanate by whatever means. To maneuver the situation within Hobyo, they even contemplated the idea of reinstating Ali Yusuf. However, the idea was dropped after they became pessimistic about the results. To undermine the resistance, however, and before the Eritrean reinforcement could arrive, De Vecchi began to instill distrust among the local people by buying the loyalty of some of them. In fact, these tactics had better results than had the military campaign, and the resistance began gradually to wear down. Given the anarchy which would follow, the new policy was a success. On the military front, on 26 December 1925 Italian troops finally overran El-Buur, and the forces of Omar Samatar were compelled to retreat to Western Somaliland.

By neutralising Hobyo, the fascists could concentrate on the Majeerteen. In early October 1924, E. Coronaro, the new Alula commissioner, presented Boqor (king) Osman with an ultimatum to disarm and surrender. Meanwhile, Italian troops began to pour into the sultanate in anticipation of this operation. While landing at Haafuun and Alula, the sultanate's troops opened fire on them. Fierce fighting ensued and to avoid escalating the conflict and to press the fascist government to revoke their policy, Boqor Osman tried to open a dialogue. However, he failed, and again fighting broke out between the two parties. Following this disturbance, on 7 October the Governor instructed Coronaro to order the Sultan to surrender; to intimidate the people he ordered the seizure of all merchant boats in the Alula area. At Hafun, Arimondi bombarded and destroyed all the boats in the area.

On 13 October Coronaro was to meet Boqor Osman at Baargaal to press for his surrender. Under siege already, Boqor Osman was playing for time. However, on 23 October, Boqor Osman sent an angry response to the Governor defying his order. Following this a full-scale attack was ordered in November. Baargaal was bombarded and destroyed to the ground. This region was ethnically compact, and was out of range of direct action by the fascist government of Muqdisho. The attempt of the colonizers to suppress the region erupted into an explosive confrontation. The Italians were meeting fierce resistance on many fronts. In December 1925, led by the charismatic leader Hersi Boqor, son of Boqor Osman, the sultanate forces drove the Italians out of Hurdia and Haafuun, two strategic coastal towns. Another contingent attacked and destroyed an Italian communications centre at Cape Guardafui, at the tip of the Horn. In retaliation, the Bernica and other warships were called on to bombard all main coastal towns of the Majeerteen. After a violent confrontation Italian forces captured Ayl (Eil), which until then had remained in the hands of Hersi Boqor. In response to the unyielding situation, Italy called for reinforcements from their other colonies, notably Eritrea. With their arrival at the closing of 1926, the Italians began to move into the interior where they had not been able to venture since their first seizure of the coastal towns. Their attempt to capture Dharoor Valley was resisted and ended in failure.

De Vecchi had to reassess his plans as he was being partially humiliated on some fronts. After one year of exerting full force, he could not yet manage to gain a total result over the sultanate. In spite of the fact that the Italian navy sealed the sultanate's main coastal entrance, they could not succeed in stopping them from receiving arms and ammunition through it. It was only early 1927 when they finally succeeded in shutting the northern coast of the sultanate, thus cutting arms and ammunition supplies for the Majeerteen. By this time, the balance had tilted to the Italians' side, and in January 1927 they began to attack with a massive force, capturing Iskushuban, at the heart of the Majeerteen. Hersi Boqor unsuccessfully attacked and challenged the Italians at Iskushuban. To demoralize the resistance, ships were ordered to target and bombard the sultanate's coastal towns and villages. In the interior the Italian troops confiscated livestock. By the end of the 1927 the Italians had taken control of all the sultanate. Defeated, Hersi Boqor and his top staff were forced to retreat to Ethiopia in order to rebuild the forces. However, they had an epidemic of cholera which frustrated all attempts to recover his force.

By November 1927, the forces of Sultan Osman Mahamuud of the Majeerteen Sultanate were also defeated. The Dubats colonial troops and the Zaptié gendarmerie were extensively used by De Vecchi during these military campaigns.

Somalis troops in Italian wars

From 5 April 1908 to 5 May 1936, the Royal Corps of Somali Colonial Troops (Regio corpo truppe coloniali della Somalia Italiana), originally called the "Guard Corps of Benadir", served as the territory's formal military corps. At the start of its establishment, the force had 2,600 Italian officers.[30] Between 1911 and 1912, over 1,000 Somalis from Mogadishu served as combat units along with Eritrean and Italian soldiers in the Italo-Turkish War.[31] Most of the troops stationed never returned home until they were transferred back to Italian Somaliland in preparation for the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.[32]

In the early 1930s, the new Italian Governors, Guido Corni and Maurizio Rava, started a policy of assimilation of the Somalis. Many Somalis were enrolled in the Italian colonial troops in the mid-1930s, actively participating in the Italian war against Ethiopia in order to unite the Ogaden region to Somalia.

In October 1935, the southern front of the Second Italo-Abyssinian War was launched into Ethiopia from Italian Somaliland. The Italian General Rodolfo Graziani commanded the invasion forces in the south.[33] Over 40,000 Somali troops served in the war, mostly as combat units (one of them was the Zaptie Siad Barre, future president of Somalia). They backed up the over 80,000 Italians serving alongside them at the start of the offensive.[34][35] Many of the Somalis were veterans from serving in Italian Libya.[32] During the invasion of Ethiopia, Mogadishu served as a chief supply base.[36]

In June 1936, after the war ended, Italian Somaliland became part of Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana) forming the Somalia Governorate. The new colony of the Italian Empire also included Ethiopia and Eritrea.[37] To commemorate the victory, an Arch of Triumph was constructed in Mogadishu and many Somalis celebrated -with a military parade under the Arch- the union of the Ogaden to Somalia[38]

After June 1940, when the Kingdom of Italy declared war on the Allies, two divisions of Somali soldiers were raised in Italian Somaliland. These were designated as the “101 Divisione Somala” and the ”102 Divisione Somala”. The divisions' initial personnel were drawn mainly from some of the colonial brigades that had fought in the conquest of Ethiopia in 1936. But soon after their formation, new recruits were enlisted in order to meet the numbers required for a standard Italian division (around 7,000 soldiers). As a result, at the start of World War II, there were 20,458 Somali soldiers in Italian Somaliland, mostly in these two new divisions.[39]

At the end of 1940, the “1st Somali Division”, commanded by General Carnevali, was sent to defend the Juba river in western Italian Somaliland, in response to Italian concerns of a British attack from British Kenya. The "2nd Somali Division", commanded by General Santini, remained initially in the area of Mogadishu as a possible reserve force, before moving to the Gelib area in February 1941. Both the divisions fought bravely.

Additionally during WW2 many Somali troops fought in the so-called Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali of the Italian Empire. The soldiers were enrolled as Dubats, Zaptié and Bande irregolari. During World War II, these troops were regarded as a wing of an Italian Army's Infantry Division, as was the case in Libya and Eritrea. The Zaptié were considered the best: they provided a ceremonial escort for the Italian Viceroy (Governor) as well as the territorial police. There were already more than one thousand such soldiers in 1922.

In 1941, in Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia, 2,186 Zaptìé plus an additional 500 recruits under training officially constituted a part of the Carabinieri. They were organised into a battalion commanded by Major Alfredo Serranti that defended Culqualber (Ethiopia) for three months until this military unit was destroyed by the Allies.[40] After heavy fighting, all the Italian Carabinieri, including the Somali troops, received full military honors from the British.[41]

Modern

Somali-Ethiopian Border War (1964)

The Somali National Army (SNA) was battle-tested in 1964 when the conflict with Ethiopia over the Somali-inhabited Ogaden erupted into warfare. On 16 June 1963, Somali guerrillas started an insurgency at Hodayo, in eastern Ethiopia, a watering place north of Werder, after Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie rejected their demand for self-government in the Ogaden. The Somali government initially refused to support the guerrilla forces, which eventually numbered about 3,000. However, in January 1964, after Ethiopia sent reinforcements to the Ogaden, Somali forces launched ground and air attacks across the border and started providing assistance to the guerrillas. The Ethiopian Air Force responded with punitive strikes across its southwestern frontier against Feerfeer, northeast of Beledweyne and Galkacyo. On 6 March 1964, Somalia and Ethiopia agreed to a cease-fire. At the end of the month, the two sides signed an accord in Khartoum, Sudan, agreeing to withdraw their troops from the border, cease hostile propaganda, and start peace negotiations.

Shifta War

The Shifta War (1963–1967) was a secessionist conflict in which ethnic Somalis in the Northern Frontier District (NFD) of Kenya (a region that is and has historically been almost exclusively inhabited by ethnic Somalis[42][43][44]) attempted to join with their fellow Somalis in a Greater Somalia. The Kenyan government named the conflict "shifta", after the Somali word for "bandit", as part of a propaganda effort.

The province thus entered a period of running skirmishes between the Kenyan Army and the Northern Frontier District Liberation Movement (NFDLM) insurgents backed by the Somali Republic. One immediate consequence was the signing in 1964 of a Mutual Defense Treaty between Jomo Kenyatta's administration and the government of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie.[45]

In 1967, Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda mediated peace talks between Somali Prime Minister Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal and Kenyatta. These bore fruit in October 1967, when the governments of Kenya and Somalia signed a Memorandum of Understanding (the Arusha Memorandum) that resulted in an official ceasefire, though regional security did not prevail until 1969.[46][47] After a 1969 coup in Somalia, the new military leader Mohamed Siad Barre, abolished this MoU as he claimed it was corrupt and unsatisfactory. The Manyatta strategy is seen as playing a key role in ending the insurgency, though the Somali government may have also decided that the potential benefits of a war simply was not worth the cost and risk. However, Somalia did not renounce its claim to Greater Somalia.[45]

1969 Coup d'état

In 1968, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke narrowly escaped an assassination attempt. A grenade exploded near the car that was transporting him back from the airport, but failed to kill him.[48]

On October 15, 1969, while paying an official visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards.[48][49] On duty outside the guest-house where the president was staying, the officer fired an automatic rifle at close range, instantly killing Shermarke. Observers suggested that the assassination was inspired by personal rather than political motives.[48]

Shermarke's assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on October 21, 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Muhammad Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[49] Barre was installed as president of the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC), the new government of Somalia. Alongside him, the SRC was led by Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Kediye officially held the title of "Father of the Revolution," and Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC.[50] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[51][52] arrested members of the former government, banned political parties,[53] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[54]

In 2005, Cambridge historian Christopher Andrew published The World Was Going Our Way, a comprehensive account of KGB operations in Africa, Asia and Latin America co-authored with the late KGB Major Vasili Mitrokhin. Based on documents drawn from the Mitrokhin Archive, it alleges that Kediye had been a paid KGB agent codenamed "OPERATOR". Ironically, the KGB-trained National Security Service (NSS), the SRC's intelligence wing, had carried out Kediye's initial arrest.[1]

Planned invasion of Uganda

When Idi Amin toppled Ugandan President Milton Obote through a military coup, Somalia and several countries in East Africa refused to recognise the new regime. Behind the scenes the militaries of Tanzania, Sudan and Somalia had co-operated and contemplated to send a joint force of several thousand troops through the Kagera Salient into Uganda to topple Amin. The three countries propped up the exiled President and his forces instead and supported their invasion of Uganda in 1972, but they failed to dislodge Idi Amin. Somalia eventually would play mediator, and through the Mogadishu agreement, more war was averted.

Rhamu Incident

The Rhamu Incident, on 29 June 1977, was a brief armed conflict between Kenya and Somalia, in which the latter invaded the Northern Frontier District on the eve of the Ogaden War. A force of 3000 Somali soldiers attacked a border post, and killed 30 Kenyan police officers and soldiers.[55] The Somali army did not stay as the objective of their mission was to invade Ethiopia from a different side through Kenya. Rhamu situated on the Ethiopian-Kenyan border lay on the road to the Sidamo region, and was considered a strategic point of entrance. The Somali government denied the invasion, and claimed to have no knowledge of the incident.

Lufthansa Flight 181

Lufthansa Flight 181 was a Lufthansa Boeing 737-230 Adv aircraft named Landshut that was hijacked on October 13, 1977, by four members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (who called themselves Commando Martyr Halime). On October 18, in coordination with the Barre administration and supported by the Somali military, the West German counter-terrorism group GSG 9 in Mogadishu, Somalia stormed the aircraft. All 86 passengers were rescued. The rescue operation was codenamed Feuerzauber, the German term for "Fire Magic". The hijacking was carried out in support of the Red Army Faction and is regarded as part of the German Autumn.

Operations in Mozambique, Rhodesia, Zambia and Burundi

During their early communist phase, Siad Barre and his military junta were initially quite supportive of various fledgling administrations and anti-colonial movements. In 1974, the Somali government invited trainee pilots and technicians from Burundi for a two-year-long capacity training programme with the Somali Air Force, which at that time was one of the strongest air powers on the continent. Before their training, the Burundi Air Force consisted of only three pilots who had received training in Egypt and France. This number grew to 18 with the help of Somali pilots and instructors.[56][57]

Barre was also the only head of state to attend Mozambique's independence celebrations. Along with fellow communists the Soviet Union and Cuba, Barre also sent martial reinforcements to assist the government of Samora Machel against Rhodesian and Portuguese forces. Rhodesian guerrillas in Maputo at the time "bragged to Portuguese correspondents that Somali tanks will be used in future operations against Ian Smith’s forces.[58]

In their struggle against the Rhodesians, Zambia appealed to other African countries for military support. On 27 June 1977, President Kenneth David Kaunda speaking to a crowd of Zambians in Lusaka announced that Somalia's armed forces were prepared to aid his country against the Rhodesians.[59] Somali Air Force pilots stood on standby to fly Zambian MiGs in case of a war.[60]

Rebel assistance and government partnership in South Africa

Although Siad Barre's administration was noted throughout its existence for its emphasis on Somalia's traditional ties with the Arab world, eventually joining the Arab League (AL) in 1974,[61] it also initially adhered to a populist communist philosophy. Consequently, Barre's regime lent support to various anti-colonial movements, including the rebellion in South Africa against that country's then-ruling apartheid government. As chairman of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1974, a rotating seat, Barre invited the ANC as an equal member and gave them a platform to have their voices heard. Barre's government also trained South African guerillas and gave them access to military hardware and naval assets.[62]

Paradoxically, however, Barre's administration was also one of the few governments on the continent that maintained regular and extensive contacts with South Africa's apartheid regime. The Somali government would grow increasingly closer with the RSA during the 1980s, as it progressively abandoned its initial communist philosophy. After fallout from the unsuccessful Ogaden War campaign, Mogadishu now sought new allies and approached Pretoria for assistance. Barre viewed the South African government as a potential partner on account of the RSA's own military struggle against communist forces. A South African delegation was subsequently hosted in Somalia's capital in May 1984, where the Somali Defense Minister declared that "RSA and Somalia have the same aggressors". Sharing of military intelligence characterized the two administrations' relationship. The South African government also hoped to secure a position as an armaments supplier for the Somali military, with a view toward using Somalia as an entree into the Middle Eastern weapons market.[63]

Ogaden War

Somalia committed to invade the Ogaden at 0300 13 July 1977 (5 Hamle, 1969), according to Ethiopian documents (some other sources state 23 July).[65] According to Ethiopian sources, the invaders numbered 70,000 troops, 70 fighter planes, 250 tanks, 350 armoured personnel carriers, and 600 artillery.[65] By the end of the month 60% of the Ogaden had been taken by the SNA-WSLF force, including Gode, which was captured by units commanded by Colonel Abdullahi Ahmed Irro. The attacking forces did suffer some early setbacks; Ethiopian defenders at Dire Dawa and Jijiga inflicted heavy casualties on assaulting forces. The Ethiopian Air Force (EAF) also began to establish air superiority using its Northrop F-5s, despite being initially outnumbered by Somali MiG-21s. However, Somalia was easily overpowering Ethiopian military hardware and technology capability. Army General Vasily Petrov of the Soviet Armed Forces had to report back to Moscow the "sorry state" of the Ethiopian army. The 3rd and 4th Ethiopian Infantry Divisions that suffered the brunt of the Somali invasion had practically ceased to exist.[66]

The USSR, finding itself supplying both sides of a war, attempted to mediate a ceasefire. When their efforts failed, the Soviets abandoned Somalia. All aid to Siad Barre's regime was halted, while arms shipments to Ethiopia were increased. Soviet military aid (second in magnitude only to the October 1973 gigantic resupplying of Syrian forces during the Yom Kippur War) and advisors flooded into the country along with around 15,000 Cuban combat troops. Other communist countries offered assistance: the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen offered military assistance and North Korea helped train a "People's Militia"; East Germany likewise offered training, engineering and support troops.[67] As the scale of communist assistance became clear in November 1977, Somalia broke diplomatic relations with the USSR and expelled all Soviet citizens from the country.

Not all communist states sided with Ethiopia. Because of the Sino-Soviet rivalry, China supported Somalia diplomatically and with token military aid. Romania under Nicolae Ceauşescu had a habit of breaking with Soviet policies and maintained good diplomatic relations with Siad Barre. By 17 August, elements of the Somali army had reached the outskirts of the strategic city of Dire Dawa. Not only was the country's second largest military airbase located here, as well as Ethiopia's crossroads into the Ogaden, but Ethiopia's rail lifeline to the Red Sea ran through this city, and if the Somalis held Dire Dawa, Ethiopia would be unable to export its crops or bring in equipment needed to continue the fight. Gebre Tareke estimates the Somalis advanced with two motorized brigades, one tank battalion and one BM battery upon the city; against them were the Ethiopian Second Militia Division, the 201 Nebelbal battalion, 781 battalion of the 78th Brigade, the 4th Mechanized Company, and a tank platoon possessing two tanks.[68] The fighting was vicious as both sides knew what the stakes were, but after two days, despite that the Somalis had gained possession of the airport at one point, the Ethiopians had repulsed the assault, forcing the Somalis to withdraw. Henceforth, Dire Dawa was never at risk of attack.[69]

The greatest single victory of the SNA-WSLF was a second assault on Jijiga in mid-September (the Battle of Jijiga), in which the demoralized Ethiopian troops withdrew from the town. The local defenders were no match for the assaulting Somalis and the Ethiopian military was forced to withdraw past the strategic strongpoint of the Marda Pass, halfway between Jijiga and Harar. By September Ethiopia was forced to admit that it controlled only about 10% of the Ogaden and that the Ethiopian defenders had been pushed back into the non-Somali areas of Harerge, Bale, and Sidamo. However, the Somalis were unable to press their advantage because of the high attrition on its tank battalions, constant Ethiopian air attacks on their supply lines, and the onset of the rainy season which made the dirt roads unusable. During that time, the Ethiopian government managed to raise and train a giant militia force 100,000 strong and integrated it into the regular fighting force. Also, since the Ethiopian army was a client of U.S weapons, hasty acclimatization to the new Warsaw Pact bloc weaponry took place.

From October 1977 until January 1978, the SNA-WSLF forces attempted to capture Harar, where 40,000 Ethiopians had regrouped and re-armed with Soviet-supplied artillery and armor; backed by 1500 Soviet "advisors" and 11,000 Cuban soldiers, they engaged the attackers in vicious fighting. Though the Somali forces reached the city outskirts by November, they were too exhausted to take the city and eventually had to withdraw to await the Ethiopian counterattack.

The expected Ethiopian-Cuban attack occurred in early February; however, it was accompanied by a second attack that the Somalis did not expect. A column of Ethiopian and Cuban troops crossed northeast into the highlands between Jijiga and the border with Somalia, bypassing the SNA-WSLF force defending the Marda Pass. The attackers were thus able to assault from two directions in a "pincer" action, allowing the re-capture of Jijiga in only two days while killing 3,000 defenders. The Somali defense collapsed and every major Ethiopian town was recaptured in the following weeks. Recognizing that his position was untenable, Siad Barre ordered the SNA to retreat back into Somalia on 9 March 1978, although Rene LaFort claims that the Somalis, having foreseen the inevitable, had already withdrawn its heavy weapons.[70] The last significant Somali unit left Ethiopia on 15 March 1978, marking the end of the war.

1982 Ethiopian–Somali Border War

The 1982 Ethiopian–Somali Border War occurred between June and August 1982 when the Ethiopian military, supported by hundreds of SSDF rebels invaded central Somalia and captured several towns. After a SNA force infiltrated the Ogaden, joined with the WSLF and attacked an Ethiopian army unit outside Shilabo, about 150 kilometers northwest of Beled weyne, Ethiopia retaliated by launching an operation against Somalia. On June 30, 1982, Ethiopian army units, together with SSDF guerrillas, struck at several points along Ethiopia's southern border with Somalia. They crushed the SNA unit in Balanbale and then occupied the town and captured Galdogob, about 50 kilometers northwest of Galcaio. After the United States provided emergency military assistance to Somalia, further Ethiopian attacks ceased. However, the Ethiopian/SSDF units remained in Balanbale and Galdogob, which Addis Ababa maintained were part of Ethiopia that had been liberated by the Ethiopian army.

Eritrean War of Independence

The Eritrean War of Independence (1 September 1961 – 24 May 1991) was a conflict fought between the Ethiopian government and Eritrean separatists, both before and during the Ethiopian Civil War. The war started when Eritrea's autonomy within Ethiopia, where troops were already stationed, was unilaterally revoked. Eritrea had become part of Ethiopia after World War II, when both territories were liberated from Italian occupation. Ethiopia claimed that Eritrea was part of Ethiopia, especially wanting to maintain access to the Red Sea. The Military of Somalia supplied the Eritreans with military hardware and provided training. The EPLF leaders and members were given Somali passports to travel the world in search of education and jobs to finance the movement, and to increase political support for their liberation struggle from other countries.[71] Following the Marxist–Leninist coup in Ethiopia in 1974 which toppled its ancient monarchy, the Ethiopians enjoyed Soviet Union support until the end of the 1980s, when glasnost and perestroika started to impact Moscow's foreign policies, resulting in a withdrawal of help. The war went on for 30 years until 1991 when the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF), having defeated the Ethiopian forces in Eritrea, took control of the country.

Architecture

Castles and fortresses

Throughout the medieval era, castles and fortresses known as Qalcads were built by Somali Sultans for protection against both foreign and domestic threats. The major medieval Somali power engaging in castle building was the Ajuran sultanate, and many of the hundreds of ruined fortifications dotting the landscapes of Somalia today are attributed to Ajuran engineers.[72]

Other castle building powers were the Gerad Kingdom and the Bari Sultanate. The many castles and fortresses such as the Sha'a Castle, the Bandar Qassim Castles and the Botiala Fortress Complex and dozens of others in towns such as Qandala, Bosaso and Las Khorey were built under their rule.

The Dervish State in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was another prolific fortress building power in the Somali Peninsula. In 1909, after the British withdrawal to the coast, the permanent capital and headquarters of the Dervishes was constructed at Taleh, a large walled town with fourteen fortresses. The main fortress, Silsilat, included a walled garden and a guard house. It became the residence of members of the Haroun, and also hosted several Turkish, Yemeni and German dignitaries, architects, masons and arms manufacturers.[73] Several dozen other fortresses were built in Illig, Eyl, Shimbiris and other parts of the Horn of Africa.

Citadels and city walls

City walls were established around the coastal cities of Merka, Barawa and Mogadishu during the Ajuran Empire period to defend the Ajuran cities against powers such as the Portuguese Empire. During the Adal Age, many of the inland cities such as Amud and Abasa in the northern part of Somalia were built on hills high above sea level with large defensive stone walls enclosing them and Zeila the Adal capital was protected by Citadels. The Bardera militants during their struggle with the Gobroon Dynasty had their main headquarters in the walled city of Bardera that was reinforced by a large fortress overseeing the Jubba river. In the early 19th century the citadel of Bardera was sacked by Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim and the city became a ghost town.

Somali city walls also acted as a barrier against the proliferation of arms usually carried by the Somali and Horn African nomads entering the cities with their caravan trains. They had to leave behind their weapons at the city gate before they could enter the markets with their goods and trade with the urban Somalis, Middle Easterners and Asian merchants.[74]

References

- Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast, 800-1900 (African Studies) by Pouwels Randall L - pg 15

- Encyclopedia of African history - Page 1406

- Ferro e Fuoco in Somaliland, da Francesco Saverio Caroselli, Rome, 1931; p. 272.

- Said S. Samatar, Oral Poetry and Somali Nationalism (Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 131, 135

- Oliver Ramsbotham, Tom Woodhouse, Encyclopedia of international peacekeeping operations, (ABC-CLIO: 1999), p. 222 ISBN 0-87436-892-8.

- Grotto galleries show early Somali life

- Nevine El-Aref (2003-08-06). "Al-Ahram Weekly | Heritage | Elkab's hidden treasure". Weekly.ahram.org.eg. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- Ancient Egypt's Humiliating Secret

- Eastern African History By Robert O. Collins Pg 53

- pg 155 - The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 4 By Richard Gray

- Jeremy Black, Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare: Renaissance to revolution, 1492–1792, (Cambridge University Press: 1996), p.9.

- pg 90 - The Ethiopians: a history By Richard Pankhurst

- pg 222 - The Portuguese Pioneers By Edgar Prestage

- Maritime Discovery: A History of Nautical Exploration from the Earliest Times pg 198

- The History of the Portuguese, During the Reign of Emmanuel pg.287

- The book of Duarte Barbosa – Page 30

- Schurhammer, Georg (1977). Francis Xavier: His Life, His Times. Volume II: India, 1541–1545. Translated by Costelloe, Joseph. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute. pp. 98–99. See also Strandes, Justus (1968). The Portuguese Period in East Africa. Transactions of the Kenya History Society. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau. OCLC 19225. pp. 111–112.

- Tanzania notes and records: the journal of the Tanzania Society pg 76

- The Portuguese period in East Africa – p. 112

- Welch (1950), p. 25.

- Stanley, Bruce (2007). "Mogadishu". In Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. (eds.). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- Four centuries of Swahili verse: a literary history and anthology – p. 11

- Shelley, Fred M. (2013). Nation Shapes: The Story behind the World's Borders. ABC-CLIO. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-61069-106-2.

- COINS FROM MOGADISHU, c. 1300 to c. 1700 by G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville pg 36

- Sudan Notes and Records - Page 147

- Transactions of the Bombay Geographical Society ..by Bombay Geographical Society pg.392

- Ciise, Jaamac (1976). Taariikhdii daraawiishta iyo Sayid Maxamad Cabdille Xasan. p. 175.

- The modern history of Somaliland: from nation to state - Page 78

- Historical dictionary of Ethiopia - Page 405

- Robert L. Hess (1966). Italian colonialism in Somalia. p. 101. ISBN 9780317113112.

- W. Mitchell. Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Whitehall Yard, Volume 57, Issue 2. p. 997.

- William James Makin (1935). War Over Ethiopia. p. 227.

- Andrea L. Stanton; Edward Ramsamy; Peter J. Seybolt (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. p. 309. ISBN 9781412981767.

- Harold D. Nelson (1982). Somalia, a Country Study. p. 24.

- Hamish Ion; Elizabeth Jane Errington (1993). Great Powers and Little Wars: The Limits of Power. p. 179. ISBN 9780275939656.

- The Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 1. 1972. p. 291. ISBN 9780717201037.

- Ruth N. Cyr; Edgar C. Alward (10 July 2001). Twentieth Century Africa. p. 440. ISBN 9781475920802.

- American Universities Field Staff. Reports Service: Northeast Africa series, Volumes 7-11. p. 112.

- Italian forces deployed in Italian East Africa, 1 June 1940

- Somalian heroism in Culqualber battle (in Italian)]

- "Not everyone knows that ... zaptiehs (in Italian)". Retrieved 2014-04-12.

- Africa Watch Committee, Kenya: Taking Liberties, (Yale University Press: 1991), p.269

- Women's Rights Project, The Human Rights Watch Global Report on Women's Human Rights, (Yale University Press: 1995), p.121

- Francis Vallat, First report on succession of states in respect of treaties: International Law Commission twenty-sixth session 6 May-26 July 1974, (United Nations: 1974), p.20

- "The Somali Dispute: Kenya Beware" by Maj. Tom Wanambisi for the Marine Corps Command and Staff College, April 6, 1984 (hosted by globalsecurity.org)

- Hogg, Richard (1986). "The New Pastoralism: Poverty and Dependency in Northern Kenya". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 56 (3): 319–333. doi:10.2307/1160687. JSTOR 1160687.

- Howell, John (May 1968). "An Analysis of Kenyan Foreign Policy". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 6 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00016657. JSTOR 158675.

- Colin Legum, John Drysdale, Africa contemporary record: annual survey and documents, Volume 2, (Africa Research Limited., 1970), p.B-174.

- Moshe Y. Sachs, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p.290.

- Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Richard Ford (1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 226. ISBN 1-56902-073-6.

- J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 8, (Cambridge University Press: 1985), p.478.

- The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac, Volume 25, (Grolier: 1995), p.214.

- Metz, Helen C., ed. (1992), "Coup d'Etat", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, retrieved October 21, 2009

- Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy, (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p.279.

- Pg 86 - Husein Dualleh - From Barre to Aideed: Somalia : the agony of a nation

- "Nostalgic memories of Burundian officers trained in Somalia".

- AMISOM Issue 25, 31 March 2011

- MOSCOW’S NEXT TARGET IN AFRICA by Robert Moss

- Facts & reports , Volume 7

- World, Volume 2 Pg 20

- Benjamin Frankel, The Cold War, 1945–1991: Leaders and other important figures in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, and the Third World, (Gale Research: 1992), p.306.

- Somalia needs African solidarity

- Roger Pfister, Apartheid South Africa and African states: from pariah to middle power, 1961–1994, Volume 14, (I.B.Tauris, 2005), pp.114-117.

- Oliver Ramsbotham, Tom Woodhouse, Encyclopedia of international peacekeeping operations, (ABC-CLIO: 1999), p.222.

- Gebru Tareke, "Ethiopia-Somalia War," p. 644

- Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978 by Mark Urban pg 42

- "Ethiopia: East Germany". Library of Congress. 2005-11-08. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- Gebru Tareke, "Ethiopia-Somalia War," p. 645.

- Gebru Tareke, "Ethiopia-Somalia War", p. 646

- Rene LaFort, Ethiopia: An Heretical Revolution?, translated by A.M. Berrett (London: Zed Press, 1983), p. 260

- Eritrea and Ethiopia: from conflict to cooperation By Amare Tekle pg 146

- Shaping of Somali Society pg 101

- Taleh W. A. MacFadyen The Geographical Journal, Vol. 78, No. 2 (August, 1931), pp. 125-128

- Tales which persist on the Tongue - Scott S. Reese pg 4