Somali Air Force

The Somali Air Force (SAF; Somali: Ciidamada Cirka Soomaaliyeed, Osmanya: 𐒋𐒕𐒆𐒖𐒑𐒖𐒆𐒖 𐒋𐒘𐒇𐒏𐒖 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒜𐒆, CCS; Arabic: القوات الجوية الصومالية, Al-Qūwāt al-Gawwīyä as-Ṣūmālīyä) is the air force of Somalia. Called the Somali Aeronautical Corps (SAC) during its pre-independence period (1954–1960), the Somali Air Force was renamed as such after Somalia gained independence in 1960. Ali Matan Hashi, Somalia's first pilot and person principally responsible for organizing the SAF, was its founder and served as its first Chief.[1] At one point, the Somali Air Force had the strongest airstrike capability in the Horn of Africa.[2] But by the time President Siad Barre fled Mogadishu in 1991, it had completely collapsed. The SAF headquarters was technically reopened in 2015.[3]

| Somali Air Force | |

|---|---|

| Ciidamada Cirka Soomaaliyeed/القوات الجوية الصومالية | |

Coat of arms of the Somali Air Force | |

| Founded | 1960 |

| Country | |

| Part of | Somali Armed Forces |

| Garrison/HQ | Afsione, Mogadishu |

| Motto(s) | Somali: Isku Tiirsada "Lean Together" |

| Ensign | |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-Chief | President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud |

| Chief of the Armed Forces | Brigadier General Odowaa Yusuf Rageh |

| Chief of the Air Force | Brigadier General Mohamud Sheikh Ali |

| Notable commanders | Brigadier General Ali Matan Hashi |

| Insignia | |

| Roundel |  |

| Fin Flash | .svg.png.webp) |

| Flag of the Air Force |  |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Attack | bayrkter |

| Fighter | s 30 f 16 |

History

Following an agreement signed between the Somali and Italian governments in 1962, Somali airmen began training in Italy with the assistance of Italian technical staff and pilots.[4] At the time, fifty Somali cadets also started training in the Soviet Union as jet pilots, later joined by over two hundred of the nation's elite NCOs and officers for general military training.[5] Most of the newly trained personnel then returned to Somalia.

The Corpo Aeronautico della Somalia was established in the 1950s, and was first equipped with a small number of Western aircraft, including two Douglas C-47 Skytrains, eight Douglas C-53 Skytrooper Dakota paratroop variants, two Beech C-45 Expeditors for transport tasks, two North American T-6 Texans (H model), two Stinson L-5 Sentinels, and six North American P-51 Mustangs for use as fighter aircraft. However, all the surviving Mustangs were returned to Italy before Somalia gained its independence in June 1960.[6] The Aeronautical Corps was officially renamed the Somali Air Force in December 1960.[7] Two Heliopolis Gomhouria light aircraft soon arrived from Egypt (Egyptian-built Zlin 381 Czech licence versions of the German Bücker Bü 181 Bestmann), and eight Piaggio P.148 trainers were donated by Italy in 1962.[7]

On 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Somali President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his bodyguards. A military coup d'état took place on October 21, 1969, the day after his funeral, in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[8] Barre then proclaimed Somalia a socialist state and initiated rapid modernization programs. Numerous Somali airmen were sent abroad to train in countries such as Italy, the United States, Soviet Union, and United Kingdom. After their training, many of these men went on to become the nation's leading instructors and fighter pilots. Fifty MiG MiG-17s were donated by the Soviets, while 29 MiG-21MFs were purchased by the Somali government.

Asli Hassan Abade was the first female pilot in the Somali Air Force. She received training on single-propellor aircraft, and later earned a scholarship to study at the United States Air Force Academy.

In July 1975, according to International Institute for Strategic Studies estimates, the Somali Air Force had three Il-28 bombers (confirmed in 2015 by author Tom Cooper), two fighter-ground attack squadrons with two MiG MiG-15s and a total of 23 MiG-17s and MiG-19s; a fighter squadron with 24 MiG-21s; a transport squadron with three Antonov An-2s and three An-24/26s; a helicopter squadron with Mil Mi-2s, Mi-4s and Mi-8s; other survivors of the early SAF years reportedly included three C-47s, one C-45, and six Italian Piaggio P.148s.[9]

Ogaden War (1977–1978)

The roles of the Air Force in the late 1970s included aerial warfare and air defence.[10][11]

In July 1977, the Ogaden War broke out after Barre's government sought to incorporate the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region in Ethiopia into a pan-Somali Greater Somalia.[11] The Somali Armed Forces invaded the Ogaden and were initially successful, capturing most of the territory. But the tide turned with the Soviet Union's sudden shift of support to Ethiopia, soon followed by nearly the entire Eastern Bloc. The Soviets halted their supplies to Barre's regime and increased distribution of aid, weapons, and training to Ethiopia's newly-communist Derg regime. They also brought approximately 15,000 Cuban troops to assist the Ethiopian military. By 1978, the Somali troops had been pushed out of the Ogaden.

Before the war, Somalia had acquired four Ilyushin Il-28 bombers. Flown by MiG-17 pilots, the aircraft could have played a decisive role in the conflict. Although only three of the Il-28s remained in service by the time war broke out,[12] they supported the initial invasion. But the planes were rendered fairly ineffective because they were used to fly high-altitude bombing missions. Once the Ethiopian Air Force began to contest the skies, the Il-28s were withdrawn from combat, remaining at their airfields until Ethiopian air strikes destroyed them. None of the Il-28s survived the war.

Status in 1980-1981

According to Nelson et al. in 1980, out of approximately twenty-one Somali combat aircraft, less than half a dozen — MiG-17s and MiG-21s — were reportedly kept operational by Pakistani mechanics.[13] Six Italian single-engine SIAI-Marchetti SF.26OW trainer/tactical support aircraft delivered in late 1979 were reportedly grounded the following year because of the lack of 110-octane gasoline in Somalia for the piston-engined aircraft. The shortage of combat aircraft was reportedly being addressed by the planned delivery of thirty Chinese Shenyang J-6 fighter-bombers, which began to arrive in the country in 1981.

The Library of Congress Country Studies wrote in 1992-93 that: "..there [were] numerous unconfirmed reports of Somali-South African military cooperation. The relationship supposedly began on December 18, 1984, when South African Foreign Minister Pik Botha visited Somalia to hold discussions with Barre. The two leaders reportedly signed a secret communiqué granting South African Airways landing rights in Somalia and the South African Navy access to the ports of Kismayo and Berbera. It was said that Somalia also agreed to sell South Africa eight MiG-21 fighters. In exchange, South Africa supposedly arranged to ship spare parts and ammunition for Hawker Hunter fighter aircraft that the United Arab Emirates had supplied to Somalia, and to cover the salaries of ten former Rhodesian Air Force pilots already in Somalia helping to train Somali pilots and technicians and flying combat missions in the north."[14]

On 28 October 1985, a Somali MiG-21 crashed.[15]

Civil war and Issaq genocide

By 1987-88, the Somali armed forces were fragmenting, as were wider state structures, and multiple insurgencies were growing, leading the country into the Somali Civil War.[16]

In response to Somali National Movement (predominantly Issaq clan) attacks on the cities of Hargeisa and Burao, Barre responded by ordering indiscriminate "shelling and aerial bombardment of the major cities in the northwest and the systematic destruction of Isaaq dwellings, settlements and water points".[17] To end what he saw as the "Isaaq problem", Barre's regime specifically targeted civilian members of the clan,[18] especially in Hargeisa and Burao.[19][20] Atrocities his forces committed against the Isaaqs included aerial strafing of fleeing refugees before they could reach the Ethiopian border.[21] Genocide scholar Adam Jones said the following of Barre's campaign against the Isaaq:

In two months, from May to July 1988, between 50,000 and 100,000 people were massacred by the regime's forces. By then, any surviving urban Isaaks – that is to say, hundreds of thousands of members of the main northern clan community – had fled across the border into Ethiopia. They were pursued along the way by British-made fighter-bombers piloted by mercenary South African and ex-Rhodesian pilots, paid $2,000 per sortie.[22]

Despite the government's continued refusal to grant foreigner access to the north to report on the situation,[23] The New York Times reported that Isaaq refugees had been strafed:

Western diplomats here said they believed that the fighting in Somalia... was continuing unabated. More than 10,000 people were killed in the first month after the conflict began in late May, according to reports reaching diplomats here. The Somali Government has bombed towns and strafed fleeing residents and used artillery indiscriminately, according to the officials.[24]

Dissolution

Metz et al. 1993 wrote that in 1990, "the SAF was organized into three fighter ground-attack squadrons equipped with J-6 and Hawker Hunter aircraft; three fighter squadrons equipped with MiG-21MF and MiG-17 aircraft; a counterinsurgency squadron equipped with SF-260W aircraft; a transport squadron equipped with An-2, An-24, An-26, BN-2, C-212, and G-222 aircraft; and a helicopter squadron equipped with Mi-4, Mi-8, and Agusta-Bell aircraft;" it was also equipped with a number of training aircraft.[25] The IISS Military Balance for 1990-91 estimated that the Somali Air Force had 2,500 personnel and a total of 56 combat aircraft, listing four Hunters, 10 MiG-17s, 22 J-6s, eight MiG-21MFs, six SF-260Ws, and a single Hawker Hunter FR.76 reconnaissance aircraft (p. 117).

By the time President Barre fled Mogadishu for his home region of Gedo in late January 1991, the country's air force had effectively ceased to exist amid the Somali Civil War. In 1993, eight MiG-21s (six MiG-21MFs and two MiG-21UMs), three MiG-15UTIs, one SF-260W and an unknown number of MiG-17 wrecks were seen at Mogadishu airport.[26][27] Three Hawker Hunters (serial numbers 704, 705 and 711) were seen at Baidoa Airport by Australian forces during the UNOSOM II intervention, but later removed.[28]

Relaunch in the 2010s

During the decades since the Somali Civil War began, former members of Barre's air force have kept in contact with each other. On October 29, 2012, 40 former senior Somali National Army and Air Force officers participated in a three-day workshop called Improving Understanding and Compliance with International Humanitarian Law (IHL), organized by AMISOM in Djibouti.[29] In October 2014, Somali Air Force cadets underwent additional training in Turkey.[30]

On 1 July 2015, Somali Defence Minister Abdulkadir Sheikh Dini reopened the headquarters of the Somali Air Force in Afisone, Mogadishu, to help re-establish the air force after a quarter century of civil war.[3]

The Somali air force is not currently operational and has no aircraft. It is composed of approximately 170 personnel: 40-50 officers, ranging from second lieutenant to colonel, and 120-130 non-commissioned officers and airmen. Turkey is delivering residential training to a group of young Somali air force personnel and intends to support further development of Somali aviation capabilities. The potential cumulative ten-year cost of redeveloping a Somali air arm is $50 million.[31]

On 6 March 2020, Somali Brigadier General Sheikh Ali met with Pakistani Air Chief Marshal Mujahid Anwar Khan in Islamabad to discuss cooperation efforts and bilateral ties between the Somali Air Force and Pakistani Air Force.[32][33]

Equipment

Somali Air Force servicemen wore green flight suits with shoulderboards indicating their rank, along with a visored pilot mask and helmet when actively flying. The Air Force would traditionally wear a sky blue (in summer) or navy blue service shirt, navy blue trousers, beret or sidecap, shoulderboards and black boots.[34] Dress uniforms consisted of a navy blue peaked cap, blazer, trousers, black formal shoes and tie and sky blue shirt. Servicemen would wear ribbons on their left breast, as well as Air Force insignia.[35]

The following table uses Nelson et al.'s 1981 Somali Air Force's aircraft estimates:

| Aircraft | Type | Country of Manufacture | Inventory | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combat aircraft | ||||

| MiG-17/F "Fresco" | Fighter-bomber | 54(MiG-17×27、MiG-17F×27)[36] | ||

| MiG-21MF "Fishbed J" | Interceptor | 33[15] or 29 | ||

| F-6C | Fighter | 30 | ||

| Aermacchi SF.260W | Light attack | 6 | ||

| Hawker Hunter FGA.76 | Attack / reconnaissance | 9 | ||

| Transport aircraft | ||||

| Antonov An-2 "Colt" | Transport | 3 | ||

| An-24/-26 | Transport | |||

| Douglas C-47 Skytrain | Transport | |||

| C-45 | Light transport | 1 | ||

| Aeritalia G.222 | Transport | 4 | ||

| Helicopters | ||||

| Mil Mi-4 "Hound" | Utility | 4 | ||

| Mil Mi-8 "Hip" | Utility | 8 | ||

| AB-204 | Utility | 1 | ||

| AB-212 | 4 | |||

| Trainers | ||||

| Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15UTI "Fagot" | Jet trainer | 4 | 3 | |

| MiG-21US Mongol B | Jet trainer | 20 | ||

| Yakovlev Yak-11 "Moose" | Trainer | |||

| Piaggio P.148 | Primary trainer | 6 | ||

| SIAI-Marchetti SM.1019 | Training, observation, and light attack aircraft | |||

The SAF purchased two Piaggio P.166-DL3 utility aircraft and two P.166-DL3/MAR maritime patrol aircraft in 1980.[37]

An Air Defence Command - seemingly a fourth service - was formed by the late 1980s. In 1987, according to U.S. DIA records, it was 3,500 strong, headquartered in Mogadishu, with seven AA gun/SAM brigades and one radar brigade.[38] Eight years later, the Somali Air Defence Force operated most of the surface-to-air missiles. As of 1 June 1989, the IISS estimated that Somali surface-to-air defence equipment included 40 SA-2 Guideline missiles (operational status uncertain), 10 SA-3 Goa, and 20 SA-7 surface-to-air missiles.[39]

Ranks of the Somali Air Force

- Officers

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | Officer cadet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lieutenant general Sareeye Guud |

Major general Sareeye Gaas |

Brigadier General Sareeye Guuto |

Colonel Gashaanle Sare |

Lieutenant colonel Gashaanle Dhexe |

Major Gashaanle |

Captain Dhamme |

First Lieutenant Laba Xídígle |

Second Lieutenant Xídígle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

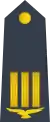

- Enlisted

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

No insignia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief Warrant Officer Musharax Sarkaal |

Warrant Officer Class 1 Sadex Xarígle |

Warrant Officer Class 2 Laba Xarígle |

Warrant Officer Class 3 Xarígle |

Sergeant Sadex Alífle |

Corporal Laba Alífle |

Lance Corporal Alífle |

Aircraftman Dable | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Luigi Pestalozza, The Somalian Revolution, (Éditions Afrique Asie Amérique latine: 1974), p.27.

- The Soviet Union in the Horn of Africa: the diplomacy of intervention and Disengagement by Robert G Patman - p. 184

- "Somalia Reopens Air Force Headquarter". Goobjoog News. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- Italy. Centro di documentazione, Italy. Servizio delle informazioni, Italy; documents and notes, Volume 14, (Centro di documentazione: 1965), p.460.

- John Gordon Stewart Drysdale, The Somali dispute, (Pall Mall Press: 1964)

- Cooper 2015, p. 13.

- Cooper 2015, p. 14.

- Mohamed Haji Ingiriis (2017) Who Assassinated the Somali President in October 1969? The Cold War, the Clan Connection, or the Coup d’État, African Security, 10:2, 131-154, DOI: 10.1080/19392206.2017.1305861

- IISS, The Military Balance 1975-76, IISS, London, 1975, p.43.

- "The Awaden War between Ethiopia and Somalia (1977-1978): Somalia attacks". DIFESA online. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Cooper 2015.

- Cooper 2015, p. 31.

- Nelson 1982, p. 249.

- Metz 1993, p. 213.

- "Mikojan MiG-21 Użytkownicy cz. 2". samolotypolskie.pl. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Robinson 2016, p. 241.

- Richards, Rebecca (24 February 2016). Understanding Statebuilding: Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-00466-0.

- Reinl, James. "Investigating genocide in Somaliland". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Fitzgerald, Nina J. (1 January 2002). Somalia: Issues, History, and Bibliography. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59033-265-8.

- Geldenhuys, p.131

- Ghalīb, Jama Mohamed (1 January 1995). The cost of dictatorship: the Somali experience. L. Barber Press. ISBN 978-0-936508-30-6.

- Jones, Adam (23 July 2004). Genocide, war crimes and the West: history and complicity. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-190-7.

- Lefebvre, Jeffrey A. (15 January 1992). Arms for the Horn: U.S. Security Policy in Ethiopia and Somalia, 1953–1991. University of Pittsburgh Pre. ISBN 978-0-8229-7031-6.

- Times, Jane Perlez, Special to the New York (13 August 1988). "Over 300,000 Somalis, Fleeing Civil War, Cross into Ethiopia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Metz 1993, p. 205.

- "Wrecked aircraft at the airbase formerly used by the Somalian Aeronautical Corps and now by the Unified Task Force in Somalia". awm.gov.au. The Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "The remains of six irreparable Somali Air Force Mig fighter aircraft on the edge of the airport ..." awm.gov.au. The Australian War Memorial. 24 March 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Hawker Hunter squadron left in the dessert. - Aviation - HMVF - Historic Military Vehicles Forum". HMVF. 18 July 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "AMISOM offers IHL training to senior officials of the Somali National Forces". AMISOM. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "Somali air force cadets in Turkey". Somalia Newsroom. 23 October 2013. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "Somalia Security and Justice Public Expenditure Review" (PDF). World Bank. 31 January 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- "Somali Air Force commander visits Air Headquarters". Dailytimes.com.pk. 5 March 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Pakistan offers support to Somalia for military training". Somali National News Agency. 5 March 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.44/tbo.ded.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/taliyaha-ciidanka-cirka-somalia.png?time=1584553927

- https://www.caasimada.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WhatsApp-Image-2020-03-04-at-6.44.46-AM.jpeg

- "Jan J. Safarik: Air Aces Home Page". Aces.safarikovi.org. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Nicolli 2012, p. 89.

- "Defense Intelligence Agency > FOIA > FOIA Electronic Reading Room > FOIA Reading Room: Africa". www.dia.mil.

- IISS Military Balance 1989–90, Brassey's for the IISS, 1989, 113.

- Ehrenreich, Frederick (1982). "National Security". In Nelson, Harold N. (ed.). Somalia: a country study (PDF). Area Handbook (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. 257. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

References

- Cooper, Tom (19 April 2015). Wings over Ogaden: The Ethiopian-Somali War (1978-1979). Africa @ War. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1909982383.

- Metz, Helen (1993). Somalia: A Country Study (PDF) (Fourth ed.). Library of Congress. Retrieved 12 July 2019. Research complete May 1992.

- Nelson, Harold (1982). Somalia: A Country Study (PDF) (Third ed.). Washington DC.: Foreign Area Studies, American University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2012. Research complete October 1981.

- Robinson, Colin D. (2016). "Revisiting the rise and fall of the Somali Armed Forces, 1960–2012". Defense & Security Analysis. 32 (3): 237–252. doi:10.1080/14751798.2016.1199122. S2CID 156874430.

- World Aircraft Information Files Brightstar publishing London File 338 sheet 4

- WorldAirForces.com, Historical Somali Aircraft

External links

- Court Chick & Albert Grandolini, with Tom Cooper & Sander Peeters, Somalia, 1980-1996, Air Combat Information Group, September 2, 2003.

- "/k/ Planes — /k/ Planes Episode 94: Cripple Fight!". Kplanes.tumblr.com. 26 February 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Somali Hunters

- Image of Somali Hunter

- Derelict Somali MiG, 1993

- ASN Aircraft accident Blackburn Beverley C.1 XL151 Aden - Beechcraft missing report 1960

- Siad's Fears: Replacement of Somali Air Force Commander change of air force chief, 1975

.jpg.webp)