Desert Mounted Corps

The Desert Mounted Corps was an army corps of the British Army during the First World War, of three mounted divisions renamed in August 1917 by General Edmund Allenby, from Desert Column. These divisions which served in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign had been formed by Australian light horse, British yeomanry, and New Zealand mounted rifles brigades, supported by horse artillery, infantry and support troops. They were later joined by Indian cavalry and a small French cavalry detachment.

The Desert Mounted Corps (DMC) comprised the ANZAC Mounted Division, the Australian Mounted Division and the Yeomanry Mounted Division, with infantry formations attached when required, as had Desert Column. In the first month of its existence, the corps continued training and patrolling no man's land preparing for manoeuvre warfare. Their first operations would be the attack, along with the XX Corps of the Battle of Beersheba. Having captured their objective they were involved in a series of battles, before the old Gaza to Beersheba line was finally broken a week later. During the pursuit they fought two Turkish armies at the Battle of Mughar Ridge before advancing to capture Jerusalem during the Battle of Jerusalem in December 1917.[lower-alpha 1]

In 1918, units of Desert Mounted Corps participated in the Capture of Jericho in February, the First Transjordan attack on Amman in March and the Second Transjordan attack on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt in April, while occupying the Jordan Valley during the summer. As a result of the German spring offensive on the Western Front the corps went through a reorganisation, when the majority of the British yeomanry regiments were dismounted and sent as infantry reinforcements to France. The Yeomanry Mounted Division and the 5th Mounted Brigade were disbanded, to be replaced by Indian cavalry regiments, which formed the 4th Cavalry Division and 5th Cavalry Division. They arrived in the Jordan Valley in May to join the corps and in September with four divisions, participated in the major offensive operations of the Battle of Sharon, a section of the Battle of Megiddo. The subsequent pursuit to Damascus followed by the Pursuit to Haritan, advances of almost 600 miles (970 km) into Turkish territory, resulted in the capture of 107,000 prisoners and over 500 pieces of artillery. At the end of October, the Armistice of Mudros ended the war against the Ottoman Empire and the corps became an occupation force in Syria. By March 1919 units were patrolling Egypt during the Egyptian Revolution of 1919. The Desert Mounted Corps was disbanded in June 1919.

Background

The main responsibility of the British Empire forces in Egypt was the defence of the Suez Canal. Its passage greatly decreased the time at sea of men and materials from India, Australasia and the Far-East. The loss of the canal to the Ottoman Empire would be a huge propaganda coup for their opponents and increase the probability that Egypt would be reconquered by them.[3]

After previously commanding the Cavalry Corps and the Third Army on the Western Front in France. General Edmund Allenby assumed command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 28 June 1917.[4] At the time the situation in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I was not promising. The British forces had withdrawn in defeat from Gallipoli and in the campaign in Mesopotamia had been surrounded and forced to surrender after the siege of Kut. In the Sinai campaign, the Turks had demonstrated their willingness to take the battle to the British, with their attack on the Suez Canal.[5] Then after some initial British success at Romani, Maghaba and Rafa, they had just suffered two comprehensive defeats in the first and second battle of Gaza.[6] Following which they had remained on the defensive.[7]

Allenby's envisaged the employment of his mounted forces on a much larger scale than his predecessor had.[8] So under the command of Lieutenant-General Harry Chauvel the Desert Mounted Corps was formed on 12 August 1917.[9][10] It had been intended to use the name II Cavalry Corps, but the name was chosen in recognition of its predecessor the Desert Column.[11] Chauvel outlined the reasons on 3 September 1920: "The name of the original Desert Column was preserved as far as possible in the title of the new Cavalry Corps, as most of the troops composing it had fought throughout the Sinai Campaign, and by them much had already been accomplished."[12] The corps initially had three divisions, the Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division (ANZ MTD DIV) with the 1st Light Horse, 2nd Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigades. The Australian Mounted Division (AUS MTD DIV) with the 3rd Light Horse, 4th Light Horse and the 5th Mounted Brigade.[lower-alpha 2] Finally the Yeomanry Mounted Division (YEO MTD DIV) with the 6th Mounted, 8th Mounted and the 22nd Mounted Brigades. Two other brigades the 7th Mounted and the Imperial Camel Corps were the corps reserve.[14][lower-alpha 3] However the dismounted strength of these brigades, of three regiments, was only the equivalent in rifle fire to an infantry battalion, as one men in every four was required to control their horses.[15][lower-alpha 4] Other components in the brigade were a horse artillery battery, a machine gun squadron, a signal troop, a field troop, a mobile veterinary section, a mounted field ambulance and an ammunition column.[17]

Reorganisation

In April 1918 in response to the German spring offensive in France, every available man that could be spared was sent to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. The Desert Mounted Corps lost the majority of its yeomanry regiments, who were dismounted and retrained to serve as infantry or machine-gun companies. This necessitated the disbandment of the Yeomanry Mounted Division. Which could have had serious consequences on the corps future operations. But the yeomanry were replaced in theatre by experienced British Indian Army cavalry regiments, that had been fighting in France since 1914. Allenby used these new regiments to raise two new divisions. The 4th Cavalry Division with the 10th Cavalry, 11th Cavalry and 12th Cavalry Brigades. The 5th Cavalry Division was slightly different having the 13th Cavalry, 14th Cavalry and the 15th (Imperial Service) Cavalry Brigades.[18]

Each of the cavalry brigades had one yeomanry and two Indian regiments, except the 15th (Imperial Service) Cavalry Brigade which had three regiments of Indian Imperial Service Troops.[19] With the move from the Sinai desert into southern Palestine there was now no need for a camel force. In June the Imperial Service Camel Brigade was also disbanded, its battalions were instead mounted on horses and used to form the 5th Light Horse Brigade.[20] Which replaced the yeomanry 5th Mounted Brigade in the Australian Mounted Division, bringing that division back up to full strength.[19] The corps now comprised four divisions but had lost its mounted reserve force, and there was no increase in the ten horse artillery batteries, it did however gain its own infantry sub unit, the 20th Indian Brigade.[19]

Formation

Between General Murray's recall in early June, and the arrival of Allenby late in June 1917, Chetwode as commander of Eastern Force gave Chauvel as commander of Desert Column, oversight for the establishment of the Yeomanry Mounted Division.[21][22][23]

On 21 June, the Imperial Mounted Division became the Australian Mounted Division. On 26 June the 6th Mounted Brigade was transferred from the Australian Mounted Division, and the 22nd Mounted Brigade from the ANZAC Mounted Division, and along with the recently arrived 8th Mounted Brigade, formed the Yeomanry Mounted Division. The 7th Mounted Brigade with the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade were corps troops.[24]

Desert Column was reorganised from two mounted divisions of four brigades, into three mounted divisions of three brigades: The ANZAC Mounted Division, Australian Mounted Division and the Yeomanry Mounted Division.[22][25]

Allenby indicated to Robertson on 12 July, that he planned to reorganise the EEF into two infantry and a mounted corps, directly under General Headquarters.[26] The structure of the EEF, would resemble the organisation of the force Allenby had commanded in France, which had reflected contemporary British combat doctrine, in the middle of 1917.[27][28] Further, in order for him to directly command these corps in the field, Allenby created two EEF headquarters. His battle headquarters was established near Khan Yunis, while the remainder of his headquarters staff stayed in Cairo, so they could deal with the political and administrative aspects of control of Egypt and martial law.[29]

On 12 August a conventional corps headquarters, designated the XX Corps and commanded by Lieutenant General P. W. Chetwode replaced Eastern Force. The headquarters of the XXI Corps commanded by Lieutenant General E. S. Bulfin (arrived from Salonika as officer commanding the 60th (London) Division) was formed, while the headquarters of Desert Column was renamed Desert Mounted Corps commanded by Lieutenant General H. G. Chauvel.[30][31][32]

Service history

1917

The first operation planned for the Desert Mounted Corps was to break through the Turkish lines, in southern Palestine, which stretched for thirty miles (48 km) from Beersheba in the east to the Mediterranean coast at Gaza in the west.[33][lower-alpha 1] Once Beersheba was secured the mounted troops would be concentrated on the British right to cut off and destroy the retreating Turkish forces.[34] Any mounted attack on Beersheba would require a march of seventy miles (110 km) over dry and unknown country. So prior to the attack a reconnaissance of the Turkish positions was carried out mapping tracks and wadi crossings. Chauvel deployed his corps, with one division forward occupying a lightly held line between Shellal and El Gamli. Which was also responsible for short patrols into no man's land and longer patrols to reconnoitre the Turkish defences. A second division supported the front line based around Abasan el Kebir. While the third division was resting at Tel el Marrakeb. Each month the divisions moved around so no one division spent longer at the front than was necessary.[35]

To prepare for the coming offensive each man was issued an officers-style saddle wallet, in which they could carry three days' rations and some spare clothing. Attached to the saddle were two nosebags with nineteen pounds (8.6 kg) or two days of grain for the horse. A third day's grain and two days' rations for the men were carried with the divisional train.[36][37] Every two weeks the forward division would move en masse towards Beersheba; leaving in the afternoon they marched all night to be in a position on the high ground in front of town by dawn the next day. There they remained all day and returned to their base the following night. These long-range patrols got the men and horses used to desert travel, with no water available for the horses from the afternoon they left until they returned.[35] These patrols were not without danger and they were often attacked by Turkish aircraft and artillery which had previously registered approach routes, wadi crossings and the high ground.[38] The patrols accustomed the Turks to the appearance of British troops in front of Beersheba, without them taking any offensive action before withdrawing again.[39] This patrol routine continued until the end of October when the corps moved forward for the coming offensive.[40]

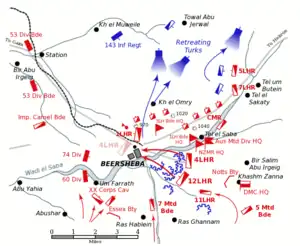

After dark 30 October the ANZ MTD DIV headed for Beersheba securing their first objectives by 08:00 the next morning. The 2nd Brigade moved on Tel el Sakaty hill, the New Zealand Brigade towards Tel el Saba, while the 1st LH Brigade was the reserve. At 10:00 the Australian Division reached their start point the Khashim Zanna hill overlooking Beersheba, sending patrols forward to reconnoitre a way into the town. At the same time the advancing 7th Brigade was forced to dismount in the face of heavy opposition from well constructed Turkish defences.[41] Now the ANZ MTD DIV was also facing heavy resistance and it was not until 13:00 that the 2nd Brigade captured Tel el Sakaty and at 13:30 cut the road north to Jerusalem.[42] Around the same time that XX Corps secured their objectives in the west.[43]

By now the New Zealand Brigade was unable to proceed being pinned down by Turkish artillery and machine-gun fire. The 3rd LH Brigade with the divisional artillery were sent to assist the attack from the south. Major-General Edward Chaytor in command of the ANZ MTD DIV, committed his reserve 1st Light Horse Brigade to support the southern attack.[44] The 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Regiments unable to approach their objectives under cover, charged in the open through artillery and machine-gun fire, until they reached a depression in the ground 1,500 yards (1,400 m) short of their target where they were able to dismount and fight forward on foot.[45] At 14:00 the 2nd Light Horse Regiment captured their objective and relieved the pressure in front of the New Zealanders, who carried out a bayonet charge capturing their own objective, 120 prisoners and several machine-guns. The last defences in front of Beersheba had been taken, but there was still a large expanse of open ground to be crossed in front of the town itself.[46]

The two divisions, less the 5th MTD Brigade, were ordered to mount up and capture Beersheba before dark. The 4th LH Brigade, three miles (4.8 km) away, which until then had seen no fighting received the order at 16:30. Brigadier-General William Grant in command of the brigade, realising that sunset was only half-an-hour away decided to charge the town from the south-east. Asking for artillery support he set out with his two available regiments. The 1/1st Nottinghamshire Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) and 1/A Battery, Honourable Artillery Company (HAC) galloped into the open, halted 2,500 yards (2,300 m) short of the town and opened fire. Which was the signal for Grants brigade to charge the Turkish defences. Jumping the two lines of trenches the brigade dismounted and within ten minutes had captured the position.[46][lower-alpha 5] Grant rallied his brigade, left a small guard force behind and charged into Beersheba and by 18:00 had secured the town, capturing 1,200 prisoners and fourteen artillery guns.[48][lower-alpha 6]

The AUS MTD DIV occupied the town while the ANZ MTD DIV put out a skirmish line to the north and north-west.[51] With Beersheba secure phase two the attack on Gaza began at 23:00 1 November and by 06:30 the next morning the front line had been penetrated and the Turkish defenders withdrawing.[52] Phase three was an attack on the open Turkish left flank, supported by the 53rd (Welsh) Division and the Camel Corps Brigade. The ANZ MTD DIV advanced to the Hebron road, near Bir el Makruneh, capturing 200 prisoners and several machine-guns en route. Operations were curtailed by lack of water in the region which necessitated the corps keeping the AUS MTD DIV in Beersheba. The town did originally have an ample water supply from seven wells but five of them had been destroyed by the Turks during the battle.[53]

Over the next five days the ANZ MTD DIV, the 5th, 7th Mounted and the Camel Corps Brigades and the 53rd Division pushed northwards and held out at Tel Khuweilfeh against a Turkish counter-attack from the 3rd Cavalry Division, the 19th, 27th and part of the 16th Divisions.[54] With all the Turkish reserves concentrated on the Desert Mounted Corps front, on 6 November when XXI Corps attacked in the west they captured all their first day objectives.[55] That evening the AUS MTD DIV moved to the Sharia region in preparation for the expected breakthrough and pursuit of the retreating Turkish forces. The ANZ and AUS MTD DIVs were ordered to move into the Turkish rear area as soon as their path was clear, the ANZ MTD DIV on the right. The YEO MTD DIV would remain behind with the 53rd Division. In part the deployment was influenced by the available water supplies to their front.[56]

On 7 November the AUS MTD DIV was fighting dismounted in support of the 60th (2/2nd London) Division and darkness had fallen before they could mount up and pursue the retreating Turks. The ANZ MTD DIV had better luck and had found a hole in the Turkish front and had advance to the train station at Umm el Ameidat on the Junction Station-Beersheba rail line, capturing 400 prisoners and a large quantity of ammunition and stores. By that night the division had moved forward a further two miles (3.2 km) east and engaged a strong Turkish rearguard position.[57] Elsewhere on 7 November the XXI Corps had eventually succeeded in capturing Gaza.[58]

Pursuit from Gaza

Over the night of 7/8 November there was a general Turkish withdrawal, the Desert Mounted Corps supported by the 60th Division were ordered to advance at dawn 8 November at their best speed to the north-west in an attempt to cut off the retreating Gaza garrison. The ANZ MTD DIV, with the 7th Mounted Brigade attached, were given the objective of Bureir, twelve miles (19 km) north-east of Gaza, to their left was the AUS MTD DIV then the 60th Division. The corps advance was met by pockets of resistance, varying in size from company to several regiments, but the speed of the British advance had prevented them forming any type of organised defences.[59] At 11:00 the Turks managed to gather enough of a force together to counter-attack the 2nd LH Brigade at Tel el Nejile which brought the ANZ MTD DIV to a halt. Chaytor pushed the 7th MTD Brigade through his centre towards Bir el Jemameh, where it was known there was a supply of water. At 13:00 just before they reached the village they also were counter-attacked, which drove back their left flank. The brigade only being saved by the arrival of the 1st LH Brigade from the west, which forced the Turks back. The light horsemen continued into the village, capturing the water pumping station intact and the high ground to the north.[60] The AUS MTD DIV and 60th Divisions were also successful and fought several small battles during which they captured a number of heavy howitzers by the simple tactic of going round and charging the position from the rear. At 15:00 the 60th Division came under heavy artillery fire from the area of Huj and requested help from some passing squadrons of the Warwickshire Yeomanry and Queen's Own Worcestershire Hussars, part of the 5th MTD Brigade. Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Cheape of the Warwicks led the force into dead ground to about 800 yards (730 m) from the Turkish guns unobserved.[61] Huj was the location of the Turkish Headquarters, the terminus of their military rail line from the coast.[62] The position consisted of a battery of field artillery another of mountain artillery and four machine-guns forward with another two artillery batteries and three heavy howitzers in a depth position at the rear. The yeomanry squadrons came out of the dead ground, charged the position from the flank and had almost reached it before the Turks managed to turn their guns around and opened fire at point blank range.[61] The fight was over in minutes the Turkish gunners killed or wounded and the positions twelve guns captured.[63][lower-alpha 7] British loses were heavy of the 170 men that started the charge seventy-five were killed or wounded.[65] With Huj captured the AUS MTD DIV were able to move in and water their horses, the successful charge also captured the main Turkish ammunition depot and their radio code books which were used to decipher Turkish signals until January 1918.[66] That afternoon the 4th Brigade was ordered to turn left and try and link up with XXI Corps advancing along the coast. Moving at their best speed, at times going around instead of fighting through Turkish positions, the brigade linked up with the Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade just before dark near Beit Hanun.[67] Also on 8 November the YEO MTD DIV had moved to the British left, to attack the Turkish right which would force them across the front of the 53rd Division and the Camel Corps Brigade at Tel KhuweiKeh. The 8th MTD Brigade began the attack but were dislodge the Turkish defenders before being ordered back to Sharia, to prepare for a pursuit of the Turkish forces withdrawing on the coastal plain.[68]

The attempt to cut off the Gaza garrison had failed, their strong rearguard resistance and the scarcity of water had both played a part in stopping the corps from fulfilling their objective. The corps instead was ordered to pursue the retreating Turkish forces. The ANZ MTD DIV objectives would be Bureir and then El Mejdel. The AUS MTD DIV on their right had Arak el Menshiye and El Faluje as their objectives. The YEO MTD DIV would advance along the coast. Just after day break on 9 November the ANZ MTD DIV moved out, meeting only light opposition the 1st LH Brigade entered Bureir at 08:30. The 2nd LH Brigade was approaching El Huleikat about an hour later when they come upon a rearguard position on the high ground to the north-west of the village, dismounting the brigade attacked capturing 600 prisoners. The 1st LH Brigade reached El Mejdel at noon, defeating the Turkish defenders in a brief fight taking 170 prisoners and capturing the water supply intact.[69] Orders were received to support the advance of XXI Corps, to do so the ANZ MTD DIV were ordered to press on to Beit Duras in the north-east. By nightfall the 1st LH Brigade had reached Esdud, and the 2nd LH Brigade after capturing a Turkish convoy and 350 prisoners en route captured another 200 prisoners at the villages of Suafir el Sharkiye and Arak Suweidan.[70]

The AUS MTD DIV spent 9 November watering its horse and did not set out until that evening, for their objective Tel el Hesi, Arak el Menshiye and El Faluje. Travelling by night the 3rd LH Brigade with an artillery battery was in front with the 4th LH and 5th MTD Brigades following on behind. At 04:30 they stopped at Tel el Hesi to wait for daylight before continuing.[71] They eventually linked up with the ANZ MTD DIV at 08:00. The YEO MTD DIV arrived some hours later, so by mid-afternoon 10 November the corps less the New Zealand Brigade was in a line from Arak el Menshiy to the coast. The corps had advanced thirty-five miles (56 km) but problems with supplies were becoming acute, the corps horses alone required over 100 tonnes (98 long tons; 110 short tons) of fodder a day. The only supply line was an un-metalled road between Gaza and Junction Station, some of it through deep sand which the army's trucks could not negotiate fully loaded.[72] To continue the advance it was decided that some of the infantry would remain in their present positions. Only the 53rd Division from XX Corps and the 52nd (Lowland) and 75th Divisions from XXI Corps continued with the advance. The Desert Mounted Corps divisions were in a bad shape having fought for several days without any rest and were short of water, some of the horses had been without water for over eighty-four hours, food for the men and forage was also in short supply. The delay allowed the Turkish forces to consolidate and by 10 November they were constructing a new defence line from Tel el Murre on the coast, along the high ground on the right bank of the Nahr Sukereir river, through Burka to Kustine.[73]

Mughar Ridge

On 10 November, the 1st LH Brigade out in front of the corps captured intact a bridge at Jisr Isdud, digging in on the north bank of the river, the brigade held out against a Turkish counter-attack supported by artillery.[74] In the east the YEO and AUS MTD DIVs located Turkish defences from Kustine, to Bayt Jibrin.[75] In order for the infantry to catch up with the corps, Allenby ordered them to hold firm until 13 November. His plan was to attack the centre with his infantry while the mounted troops moved around their open right flank. The YEO MTD DIV which was still in relatively good shape was ordered, along with the Camel Corps Brigade and the New Zealand Brigade, to move to the coast and relieve the Anzac Mounted Division, except the 1st LH Brigade holding the bridgehead. The AUS MTD DIV would remain in the east around Zeita, defending the British right flank.[76] Brigadier-General Charles Cox in command of the 1st LH Brigade was ordered to enlarge their bridgehead. Unable to find a suitable ford, during the night of 11/12 November the 2nd Light Horse Regiment swam their horses across the river, then captured the Turkish position on the Tel el Murre hill with a bayonet charge.[77] Later the same day the 52nd (Lowland) and 75th Divisions crossed the bridgehead and within ninety minutes had captured Burka.[78]

On the right flank the patrolling by the AUS MTD DIV had convinced the Turks that they were confronted there by a much larger force. At 13:00 they sent a force of around 5,000 men in two pincer columns against Balin defended by the 5th MTD Brigade. The manoeuvre almost surrounded the British position, 'B' Battery H.A.C. was forced to withdraw its guns by sections, firing at point blank range, to cover the section pulling back. The brigade had only just managed to extradite itself from the village, when the Turks turned on the 3rd LH Brigade at Berkusie. The situation was critical so Major General H Hodgson ordered the division to withdraw to Bir Summeil and Khurbet Jeladiyeh. As the order was going out a train loaded with Turkish reinforcements arrived and attacked the 5th MTD Brigade.[79] But by now the divisions artillery was in position to intervene and broke up the Turkish attack allowing the 5th MTD and 3rd LH Brigades to withdraw to Summeil, where they were able to hold on against the Turkish offensive.[80]

A new British assault began on 13 November, with the YEO MTD DIV on the left of the two infantry divisions and the AUS MTD DIV to their right. The 7th MTD Brigade replaced the exhausted 5th MTD Brigade in the AUS MTD DIV and the 2nd LH Brigade became the corps reserve.[81] At 08:00 the 8th MTD Brigade had reached the village of Yebnah, which was only held by a small Turkish force. Fighting through they made for the villages of Zernuka and Kubeibe, the last Turkish positions on their right.[82] Both villages were heavily defended with several machine-guns and the brigades progress faltered. Keeping the 6th MTD Brigade as the YEO MTD DIV reserve the 22nd MTD Brigade was dispatched to force a way between Zernuka and El Mughar and occupy Aqir in the Turkish rear, but the 22nd were also stopped by heavy machine-gun fire. The 52nd Division attempting to attack El Mughar were also stopped in their tracks and requested the YEO MTD DIV assist them by attacking the village from the east.[83] The 6th MTD Brigade were given the task, Brigadier-General C.A.C. Godwin ordered the Royal Buckinghamshire Yeomanry and the Queen's Own Dorset Yeomanry to charge across two miles (3.2 km) of open ground, supported by their own artillery and machine-guns, to assault the village.[84] Within minutes the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry had charged through the Turkish lines securing the position. The Dorset's had a more difficult approach but both regiments were successful, for the loss of 129 men and 265 horses killed and wounded, they had killed 600 Turkish soldiers, captured another 1,100 prisoners, three artillery guns and several machine-guns. The 22nd MTD Brigade then pushed on to assault Aqir but was held up by strong Turkish defences, but they did capture another seventy prisoners and some machine-guns.[85]

The 75th Division had also secured their objective and held out against a Turkish night time counter-attack and on the right the AUS MTD DIV captured Tel el Turmus virtually unopposed.[86] The next day the Turkish forces were withdrawing and the corps were once again order in pursuit. Early in the day the AUS MTD DIV captured El Tine train station with large quantities of ammunition and other stores. Pushing on they penetrated behind the previous Turkish front line to a position two miles (3.2 km) east of Junction Station. The YEO MTD DIV, leading the 52nd Division captured Aqir and Naane unopposed except for some artillery shelling.[87] The British attack had divided the Turkish forces in two. The larger contingent headed inland over the hills towards Jerusalem, pursued by the YEO MTD and AUS MTD DIVs. While the smaller force headed up the coast followed by the ANZ MTD DIV. The 1st LH and New Zealand Brigades captured Kubeibe and Zernuka in the morning, and continued towards Ramleh and Khurbet Surafend. While the Camel Corps advanced up the sand dunes on the extreme left. At 14:00 the New Zealand Brigade encountered a Turkish force at Ayun Kara but defeated them without much difficulty. Then half an hour later the brigade was surprised and surrounded only holding out following a bayonet charge. Reinforced by the 1st Light Horse and Camel Corps Brigades the New Zealanders held out for the rest of the day.[88] The advance continued and on 15 November the ANZ MTD DIV captured Ramleh and 350 prisoners with no opposition, followed the next day by the New Zealand Brigade entering Jaffa. By now the Turkish forces were entrenched along the north bank of the Nahr el Auja River and the ANZ MTD DIV was ordered to halt, while the army concentrated on capturing Jerusalem.[89] Since Beersheba the Desert Mounted Corps had advanced eighty-five miles (137 km) captured 5,720 prisoners, sixty artillery guns, fifty machine guns and large stocks of ammunition and other equipment.[90]

Jerusalem

On 17 November the YEO MTD DIV pursuing the retreating Turkish forces through the hills in front of Jerusalem, came upon a strong rearguard position, on the ridge line between the villages of Sidun and Abu Shusheh. A force of 4,000 men supported by artillery and machine-guns the majority of which around Abu Shusheh, with a depth position to its south. Major-General George de S. Barrow ordered the 22nd MTD Brigade to attack the position from the north, the Camel Corps Brigade from the north-west and the 6th MTD Brigade from the south-west.[91] At 07:00 the 22nd MTD and Camel Corps Brigades attacked on foot. Goodwin in command of the 6th MTD Brigade decided to attack mounted. He dispatched half of his machine-gun squadron and a squadron from the Berkshire Yeomanry forward to provide covering fire assisted by the Berkshire Battery R.H.A. located 3,500 yards (3,200 m) south-west of the village. He ordered the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry to charge Abu Shusheh, the remainder of the Berkshire Yeomanry on their left would charge a spur to the north of the village. The Queen's Own Dorset Yeomanry would be the brigade reserve, protecting the brigades right flank. The artillery and machine-guns opened fire as the Berkshire Yeomanry moved into the open towards the village, but confronted by heavy machine-gun fire were forced to take cover in a defile. At the same time the Dorset Yeomanry moved around to the south to take that position from the rear, attracting the attention of the machine-gunners. Seeing this the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry came out of cover and charged the village. The Buckinghamshire Yeomanry and the two squadrons of Berkshire Yeomanry reached the village around the same time as the Dorset Yeomanry charged home on the machine-gun position. The position was secured but while clearing up the brigade was counter-attacked, which was broken up, suffering heavy losses, by the brigades artillery.[92] By 09:00 the position was secured with over 400 Turkish dead, 360 prisoners and several machine-guns captured, British losses were thirty-seven dead and wounded. The Turkish survivors were pursued north by the 22nd MTD Brigade, who caught some prisoners, but an unknown number escaped into the surrounding hills.[93]

By now the corps had been operating for seventeen days, advanced 170 miles (270 km) without rest and had again outstripped it supply lines. The country they were now operating in was unsuitable for horses, but the army's transport vehicles were insufficient to bring the infantry divisions forward quickly.[94] Allenby hoped to surrounded Jerusalem cutting the city off from any reinforcements, forcing its leaders to surrender without a fight. On 18 November the Yeomanry Division then at Ludd, was directed to advance as fast as possible, on a line Berfilya, Beit Ur el Tahta, to Bire. In the difficult terrain the 8th Mounted managed to reach Beit Ur el Tahta and the 22nd Brigade Shilta by that night. At the same time the 3rd LH and 4th LH Brigades from the AUS MTD DIV lead the 52nd and 75th Divisions up the main Jerusalem road to Kuryet el Enab, intending to turn north-east to the Nablus road.[95] The 5th MTD Brigade moved independently along the Wadi Surar, protecting their right flank. The 53rd Division left Hebron to the east of Jerusalem to cut the Jericho road. To ease the supply problem on 19 November, the 75th Division took over from the AUS MTD DIV, which withdrew to El Mejdel.[96] The 8th MTD and 22nd MTD Brigades continued their advance to Beitunia and Ain Arik, but around midday were confronted by a large Turkish force. Unable to make any progress both brigades held firm waiting for the 6th MTD Brigade to catch up with them. The next day (20 November), the 6th MTD and 8th MTD Brigades tried to reach Beitunia but were again held by the Turkish force and had made no headway by nightfall. In a concentrated effort all three brigades tried to take Beitunia on 21 November. The 6th MTD and 8th MTD Brigades in a direct assault from the west, while the 22nd MTD Brigade tried from further north to get around the right flank. The Turkish defenders had been reinforced, and outnumbered the yeomanry by three to one, and the attack failed.[97] Several more attempts to capture the position also failed and the division was finally forced back that afternoon by even more Turkish reinforcements. Their situation now untenable they were ordered to withdraw after dark back to Beit Ur el Foka.[98] Two days later on 23 November a lack of forage forced the division to send all their horses back to Ramleh.[98]

Away from the mountains the ANZ MTD DIV deployed in observation posts along the River Auja, and had located four crossing points across the river. A bridge at Khurbet Hadrah and three fords. One two miles (3.2 km) east of the bridge at Muannis, a second at Jerisheh and the third at the river mouth. On 24 November the division was ordered to establish one of more bridgeheads on the opposing bank. Chaytor decided to force a crossing at the river mouth with diversionary attacks at the other three crossings.[98] The only force he had available was the New Zealand Brigade supported by two infantry battalions from the 54th (East Anglian) Division, that had just arrived at the front.[99] The infantry made the diversionary attacks while the New Zealanders successfully crossed at the river mouth defeating the small guard force. They then turned and charged upriver clearing the Turkish defences. One of the infantry battalions crossed the river forming two bridgeheads at Muannis and at the Khurbet Hadrah bridge. Two New Zealand squadrons were pushed into the high ground to the north as a covering force while a third guarded the crossing at the river mouth. That night the divisions engineers built a pontoon bridge across the river at Jerisheh, which was defended by the second infantry battalion. In daylight the Turks responded with an attack in force driving back the two covering squadrons and attacking the bridgehead at Khurbet Hadrah.[100] The New Zealand squadron holding the ford at the river mouth reinforced by a New Zealand regiment attacked the Turkish right flank, while the divisions third regiment moved to support the Khurbet Hadrah bridgehead. But by 08:30 the Turks had driven the bridgehead at Khurbet Hadrah back over the river, soon after followed by the other bridgeheads. The Turkish assault made no attempt to follow the retreating division back over the river.[101]

By 27 November the YEO MTD DIV in the hills had been reduced to around 800 men, less than an infantry battalion. Unable to hold a strong defensive line the division commenced patrolling between a small number of defended posts. One post near Zeitun composed of three officers and sixty men was attacked that afternoon by a Turkish battalion, supported by artillery and machine-guns. By nightfall they had been reduced to twenty-eight men but still held out.[101] Two understrength troops were sent to reinforce the position, which managed to hold on against several attacks but had to be withdrawn in the morning. The Turks occupied the village which gave them an observation point looking out over the surrounded countryside. The YEO MTD DIV had to withdraw to avoid being overlooked during which it was continuously attacked by the Turks and was in danger of being surrounded. To relieve the situation the reserve AUS MTD DIV Australian Division and 7th MTD Brigade were ordered to march through the night to their assistance. The 7th MTD Brigade arrived at Beit Ur el Tahta at 05:00 28 November just in time to break up an attack on the 22nd MTD Brigade. A brigade from the 52nd Division was sent to cover the yeomanry exposed left flank. Discovering that the Turks had broken through a gap in the yeomanry defences and cut their supply route, the infantry successfully attacked and drove them back but were unable to dislodge a larger force located at Saffa.[101] The AUS MTD DIV arrived at Khurbet Deiran that morning after marching twenty-one miles (34 km), the 4th LH Brigade relieved the 6th MTD at 17:00. The fighting continued on and off throughout the night, often at close range but the yeomanry now supported by the Australians held on. The next day both divisions were withdrawn and replaced by two infantry divisions,[102] Allenbys plan worked Jerusalem surrounded surrendered on 9 December.[103] Between 31 October and 9 December the corps had advanced ninety miles (140 km), captured 9,500 prisoners and eighty artillery guns.[104]

Amman

January 1918 started with the British holding a line of trenches to the north of Jaffa and Jerusalem. The Desert Mounted Corps was withdrawn to Gaza to rest and refit.[104] In February the ANZ MTD DIV and the 60th (London) Divisions were relocated to Bethlehem and on 18 February were given orders to move into the Jordan Valley and capture Jericho. The advance began the next morning and by nightfall the ANZAC Division had reached El Muntar, only four miles (6.4 km) south of the Jericho. Travelling by narrow tracks the 1st LH Brigade reached the Dead Sea at dusk. By dawn 21 February the New Zealand Brigade reached Nebi Musa without opposition, and the 1st LH Brigade entered a deserted Jericho at 08:00. The divisions patrols located the Turkish forces holding a bridgehead on the west bank of the River Jordan at El Ghoraniyeh, to the east of Jericho, and in a position along the Wadi el Auja to the north of the city.[105]

The campaign had settled down into static trench warfare in the west, however in the east Allenby decided to raid the Hedjaz Railway at Amman, to destroy the viaduct and railway tunnel. The ANZ MTD DIV, with the Camel Corps Brigade and 60th Division would carry out the raid.[106] The plan was for 60th Division would force a river crossing, then the mounted force would head for Amman blow up the viaduct, tunnel and as much of the rail line as possible then withdraw, the infantry would remain on the east bank holding the bridgehead.[107] On 21 March by 08:00 the infantry had completed a pontoon bridge across the Jordan six miles (9.7 km) south of El Ghoraniyeh and by 12:00 had a brigade on the eastern bank. Attempts to cross at El Ghoraniyeh failed until 23 March when in the early morning a raft crossing was made and by 04:00 part of the New Zealand Brigade was across the river and heading north.[108] Eight hours later they had seized the high ground above El Ghoraniyeh, capturing seventy prisoners and several machine-guns. By that night a second pontoon bridge had been constructed at Hajlah, and three more at Ghoraniyeh. The whole raiding force were across the river before daylight on 24 March. The 1st Light Horse Brigade moved to El Mandesi three miles (4.8 km) to the north, covering the 60th Divisions attack on El Haud and Shunet Nimrin. After heavy fighting El Haud was captured at 15:00, a New Zealand squadron supporting the infantry, then attacked the Turkish right who retired to Es Salt. The 2nd LH and Camel Corps Brigades advanced up the Wadi Kefrein reaching Rujm el Oshh by 15:30. The remainder of the New Zealand Brigade advanced up the Wadi Jofet to El Sir, but the infantry had only advanced four miles (6.4 km) by nightfall.[109] Rain started that night turning what were marked as tracks on their maps into small rivers. Struggling against the weather the 2nd Brigade travelled all night and reached Ain el Hekr by 04:30, only having covered sixteen miles (26 km) in twenty-fours hours. It was even worse for the Camel Corps Brigade following behind their last unit arrived at Ain el Hekr fifteen hours later.[110] The advance continued and although still raining the terrain was easier to cross and the leading troops of the two brigades linked up with the New Zealand Brigade at 05:30 26 March one mile (1.6 km) to the east of El Sir. The three brigades had been marching for three nights and two days and Chaytor decided to rest, for twenty-four hours, instead of pressing on and assaulting Amman. During the rest period a patrol from the 2nd LH Brigade attacked a Turkish position capturing 170 prisoners while another destroyed thirty German trucks and a car that were stuck in mud. That evening the 1st LH Brigade and 60th Division reached a deserted El Salt. The infantry were as exhausted as the mounted troop having fought for three days and nights to reach their present position and they also rested for twenty-four hours.[111] Overnight Chaytor despatched two small patrols to blow up the rail line to the north and south of Amman. The group from the 2nd LH Brigade heading north come upon a large body of Turkish cavalry and were forced to turn back. The New Zealand party were more successful and destroyed a length or track seven miles (11 km) south of Amman.[112]

The ANZ MTD DIV resumed the raid early on 27 March, with an infantry brigade and two mountain artillery batteries moving in support from Es Salt. The Turks in the meantime had used the respite to bring up reinforcements if their own. Chaytor ordered the New Zealand Brigade to cross the Wadi Amman, south-west of Amman and secure the high ground overlooking the town from the south. A battalion from the Camel Corps Brigade would accompany them to destroy the rail line located there. The 2nd LH Brigade were ordered to move around to the rail line north of Amman and destroy the line there.[113] Once that was done the brigade would attack Amman from the north-west, the remainder of the Camel Corps Brigade would attack from the west, while the infantry would continue to advance in support from Es Salt. The mounted brigades set out at 09:00, struggling through the mud it was not until 15:00 that the New Zealanders reached their objective. Their camel battalion started their demolition work and engaged a Turkish train with their machine-guns forcing it to pull back.[114] The 2nd LH Brigade by 11:00 had got within three miles (4.8 km) of their objective, when they were attacked by a large Turkish force with artillery support. The Camel Corps Brigade heading directly for Amann was engaged by several machine-guns and could make no progress and the New Zealand Brigade was also attacked by increasing numbers of Turkish troops. Chaytor ordered the three brigades to hold firm until the infantry could arrive and support them. That night a small group from the 2nd LH Brigade did manage to infiltrate the Turkish lines and destroyed a rail bridge near Khurbet el Raseife.[115]

Daylight brought down Turkish artillery on the divisions positions, around noon two infantry battalions caught up with the division. Chaytor decided on an immediate attack, with the infantry positioned between the 2nd LH and Camel Corps Brigades.[116] The assault started at 14:00 and got to within 1,000 yards (910 m) of the Turkish lines when the 2nd LH Brigade were counter-attacked. The whole British attack faltered and they withdrew a short distance into a night time defensive position. The remainder of the infantry brigade and two mountain artillery batteries arrived at midday the next day.[115] Turkish reinforcements had also arrived during the day and continued their attack against the 2nd LH Brigades position. To their rear at Es Salt the 1st LH Brigade came under attack from the 3rd Turkish Cavalry Division and two infantry brigades.[117] Chaytor planned a new attack that night, the New Zealand Brigade were tasked to capture a large hill one mile (1.6 km) south-east of Amman. The Camel Corps and infantry would attack the town while the 2nd Brigade was to carry out diversionary operations in the north. The assault started at 02:00 the New Zealanders reached the top of the hill without the Turks firing a shot. But were then engaged by heavy machine-gun fire, followed by an infantry counter-attack at dawn.[118] The attack by the Camel Corps and infantry brigade was initially successful capturing the first line of trenches with 200 prisoners. By 09:00 the Camel Corps Brigade were about 800 yards (730 m) from the main Turkish position when it came under heavy machine-gun fire and an infantry counter-attack was launched against the infantry brigade. The counter-attack was defeated but the British infantry were under an almost constant threat from the Turks and were just able to hold where they were. More Turkish reinforcements arrived at 10:00 and attacked the New Zealanders, which was defeated with support from the Somerset Battery R.H.A which had just arrived after a thirty-hour march. Later in the morning the New Zealanders and Camel Brigade both fought off another direct attack on their positions.[119] That afternoon the infantry tried once again to reach Amman, but machine-gun fire from both flanks forced them to withdraw. In the face of ever increasing Turkish reinforcement Chaytor decided they had no hope of taking Amman. The British were now being attacked at Es Salt and at Amman, with no reserves available Major-General John Shea of 60th Division but in overall command of the raiding force decided to call off the operation. That night the ANZ MTD DIV, Camel Corps Brigade and attached infantry pulled back reaching Ain el Sira the next evening. On 31 March the Turkish attacks at Es Salt continued all day until 23:00 when having made no progress they finally broke off the engagement.[120] The last of the British troops crossed to the west bank of the Jordan late on 2 April. In the twelve days fighting 1,600 men had been killed, wounded or were reported missing.[121] Turkish losses were 1,00 taken prisoner, the stores and ammunition at El Salt and an estimated 1,700 dead and wounded. The infantry had managed to hold a bridgehead at Ghoraniyeh and a second bridge was built four miles (6.4 km) further north at the mouth of the river Auja.[122]

Es Salt

During April the Turkish forces on the east bank had increased to around 8,000 men based on Shunet Nimrin.[18] Allenby proposed a raid in connection with their Arab allies to cut off and destroy them. The raids timing come during the corps reorganisation and the only forces available were the ANZ MTD and AUS MTD DIVs, two infantry brigades from 60th Division, and the Imperial Service Cavalry and Infantry Brigades.[123] The raid commenced 29 April the AUS MTD DIV reinforced with the 1st LH and 2nd LH Brigade crossed the Jordan and moved into the mountains. The 5th MTD and 2nd LH Brigades made for El Haud, the 3rd LH Brigade headed towards El Salt, the 4th LH and the reserve 1st LH Brigade headed for the Turkish controlled bridge at Jisr el Damieh.[123]

The 4th LH Brigade reached the Jisr el Damieh bridge at 06:00, the leading 11th Light Horse Regiment attempted to seize the bridge but the Turkish defenders were well dug in and the attempt failed. A second brigade attempt was also defeated by the strength of the Turkish defenders. Instead the brigade, with the divisions three R.H.A batteries, took up a defensive position covering the track from Jisr el Damieh to El Salt. That afternoon the batteries were used to disperse a large column of Turkish troops that were marching towards them.[124] The infantry attacked the Turks at Shunet Nimrin, but could only occupy the forward positions. The large numbers of defenders preventing any further progress. At 15:00 the corps ordered the reserve 1st LH Brigade to follow the main force towards El Salt. Where the 3rd LH Brigade were already approaching the town but were engaged by a Turkish position to the north-west. A bayonet charge by the 9th and 10th Light Horse Regiments captured the position. The 8th Light Horse Regiment then galloped into the town which was full of Turkish soldiers. By 19:00 the town was secured with 300 prisoners, several machine-guns and the Fourth Army headquarters captured. The AUS MTD DIV, 1st LH, 2nd LH Brigades and two artillery batteries travelling through the night reached Es Salt early on 1 May.[125] The force deployed brigades to the east, north, and west while the 5th MTD Brigade moved on Shunet Nimrin.[126]

At 07:30 around 4,000 Turkish soldier appeared on the east bank of the Jordan and advanced on the 4th LH Brigade position from the east. At the same time another 1,000 infantry and 500 cavalry approached from the west. The three artillery batteries with the brigade opened fire on the approaching Turkish troops and Turkish artillery located on the west bank returned their fire.[126] Around 10:00 they managed to overwhelm a small outpost the survivors from the two squadrons were pulling back to the main position when an all out Turkish assault on the brigade started. Outnumbered by about five to one the brigades right flank was turned. Grant in command of the brigade ordered an immediate withdrawal south. Some Turkish troops had got behind the brigade and were blocking the route south. Now fighting at close quarters the brigade was in danger of being overrun. The New Zealand Brigade fifteen miles (24 km) away dispatched two of its regiments to assist the 4th LH Brigade.[127] On the brigade right flank the 4th Light Horse Regiment was covering the retreat of the three artillery batteries. 'A' Battery H.A.C. was on the right, the Nottinghamshire Battery R.H.A. in the centre and 'B' Battery H.A.C. in the south. The two northern batteries 'A' and the Notts attempted to withdraw by sections covering each other firing over open sights. Gradually the artillerymen and horses were shot down and the guns backed into a position with no exit. Forced to make a stand as the Turks had advanced to within 200 to 300 yards (180 to 270 m) on three sides, the batteries ammunition ran out. The last surviving gunners and light-horsemen abandoned the guns and escaped by climbing into the hills. 'B' Battery H.A.C., less one gun that overturned, did escape being encircled and repositioned further south to cover the brigade withdrawal.[128] By midday the brigade had found a new defensive position in a small wadi. Chaytor now arrived to find out for himself what the situation was and ordered the brigade to withdraw further, to a new position north of the Umm el Shert track. During which the two New Zealand regiments arrived and a new defence line was established from the Jordan to the foothills. The Turks attacked the new defence line three times during the day but were beaten back suffering heavy losses.[129]

Elsewhere at dawn the 5th MTD Brigade had left Es Salt for El Howeij arriving at 13:00 but were unable to dislodge the large Turkish force guarding the road bridge into the town. To assist them the 1st LH Brigade were ordered to attack El Haud in the west. By the end of the day the Turkish defenders were still holding off both brigades. That night the 2nd LH Brigade was also sent to assist the 5th MTD and both were ordered to support 60th Divisions dawn attack on Shunet Nimrin and El Haud on 2 May. With the 4th LH Brigades position in danger the 1st LH Brigade were ordered to support them by defending the track from Umm el Shert. The whole British force was now in danger from the Turkish 3rd Cavalry Division and part of an infantry division moving towards El Salt from the north-west and another detachment heading towards Amman from the east.[130] The attack on Shunet Nimrin by 60th Division began at dawn but they made little progress confronted by a strong Turkish force. At 08:00 5th Brigade attacked their right flank at El Howeij bridge, by 10:30 2nd LH Brigade were still en route to their objective El Hand. At the same time 3rd LH Brigade at Es Salt was attacked by a large Turkish Force. Under heavy pressure their lines were forced back a little and a regiment from the 1st LH Brigade was sent to their aid. This reinforcement made little difference and another 1st Brigade regiment was sent to support them an hour later. The fortunate arrival of a supply column with 100,000 rounds of small-arm ammunition and 300 artillery rounds assisted the 3rd LH Brigade defence. Their machine-guns which until then had been conserving ammunition were able to break up the Turkish assault.[131]

The British advance was floundering the 2nd LH and 5th MTD Brigade commanders informed the divisional commander Major-General Hodgson that they could not reach their objectives by nightfall. He ordered them to continue as good as possible to assist the infantry attacking Shunet Nimrin.

Order of battle

1917

- Desert Mounted Corps Commander Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Chauvel

- General Staff, Brigadier General Richard Howard-Vyse

- Deputy Adjutant and Quartermaster-General, Brigadier General E. F. Trew

- GOC Royal Artillery, Brigadier General A. D'A. King[132]

- Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division commander Major-General Sir Edward Chaytor[133]

- 1st Light Horse Brigade commander Brigadier-General Charles Frederick Cox

- 2nd Light Horse Brigade commander Brigadier-General Granville Ryrie

- New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade commander Brigadier-General William Meldrum

- XVIII Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery (T.F.) (RHA)

- 1/1st Inverness-shire Royal Horse Artillery

- 1/1st Ayrshire Royal Horse Artillery

- 1/1st Somerset Royal Horse Artillery

- Divisional Ammunition Column

- A. and N. Z. Field Squadron[134]

- Australian Mounted Division commander Major-General Sir Henry West Hodgson[135]

- 3rd Light Horse Brigade commander Brigadier-General Lachlan Chisholm Wilson

- 4th Light Horse Brigade commander Brigadier-General William Grant

- 5th Mounted Brigade commander Brigadier-General Percy Desmond FitzGerald (to November 1917) Brigadier-General Philip James Vandeleur Kelly

- XIX Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery (T.F.)

- Yeomanry Mounted Division commander Major-General Sir George de S. Barrow[134][135]

- 6th Mounted Brigade commander Brigadier-General Charles Godwin

- 8th Mounted Brigade commander Brigadier-General C. S. Rome

- 22nd Mounted Brigade commander Brigadier-General Frederick Fryer (to December 1917) Brigadier-General P. D. FitzGerald

- XX Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery (T.F.)

- 1/1st Berkshire Royal Horse Artillery

- 1/1st Hampshire Royal Horse Artillery

- 1/1st Leicestershire Royal Horse Artillery

- Divisional Ammunition Column[135]

- Corps Reserve

- 7th Mounted Brigade commander Brigadier-General John Tyson Wigan (to December 1917) Brigadier-General Goland Vanhalt Clarke

- Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry

- South Nottinghamshire Hussars

- Hertfordshire Yeomanry

- 1/1st Essex Royal Horse Artillery

- Brigade Ammunition Column[136]

- Imperial Camel Corps Brigade commander Brigadier-General Clement Leslie Smith

- 1st (Australian) Battalion

- 2nd (British) Battalion

- 3rd (Australian) Battalion

- 4th (Australian and New Zealand) Battalion

- Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Battery Royal Garrison Artillery[136]

- 7th Mounted Brigade commander Brigadier-General John Tyson Wigan (to December 1917) Brigadier-General Goland Vanhalt Clarke

1918

During the reorganisation in April and May 1918 the Yeomanry Division was disbanded when most of the yeomanry were sent to the western front. They were replaced by the following –

- 4th Cavalry Division commander Major-General Sir George Barrow[136]

- 10th Cavalry Brigade commander Brigadier-General Wilfrith Gerald Key Green

- 11th Cavalry Brigade commander Brigadier-General Charles Levinge Gregory

- 1st County of London Yeomanry

- 29th Lancers

- 36th Jacob's Horse[19][137]

- 12th Cavalry Brigade commander Brigadier-General John Tyson Wigan

- Staffordshire Yeomanry (Queen's Own Royal Regiment)

- 6th King Edward's Own Cavalry

- 19th Lancers (Fane's Horse)[19][137]

- 20th Brigade R.H.A

- 5th Cavalry Division commander Major-General H. J. M. MacAndrew[137]

- 13th Cavalry Brigade commander Brigadier-General P. J. V. Kelly (to September 1918) Brigadier-General George Alexander Weir

- Royal Gloucestershire Hussars

- 9th Hodson's Horse

- 18th King George's Own Lancers[19][137]

- 14th Cavalry Brigade commander Brigadier-General G. V. Clarke

- Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry

- 20th Deccan Horse

- 34th Prince Albert Victor's Own Poona Horse[19][137]

- 15th (Imperial Service) Cavalry Brigade commander Brigadier-General Cyril Rodney Harbord

- Divisional artillery

- 13th Cavalry Brigade commander Brigadier-General P. J. V. Kelly (to September 1918) Brigadier-General George Alexander Weir

- 20th Indian Brigade

- 110th Mahratta Light Infantry

- Alwar Infantry (I.S.)

- 4th Battalion, Gwalior Infantry (I.S.)

- 1st Battalion, Patiala Infantry (I.S.) (Rajindra Sikhs)[19]

During the April and May reorganisation, most of the 5th Mounted Brigade were sent to the Western Front. The brigade was disbanded and replaced by the

- 5th Light Horse Brigade commanded by Brigadier General C. Macarthur Onslow.

- 14th Light Horse Regiment (Australians transferred from the Imperial Camel Brigade)

- 15th Light Horse Regiment (Australians transferred from the Imperial Camel Brigade)

- 16th Regiment consisting of Mixte de Marche de Palestine et Syrie (French Régiment Mixte de Cavalerie) French Chasseurs d’Afrique (two squadrons) and Spahis (one squadron).[138][139][140]

Chaytor's Force commanded by Major General Edward Chaytor, briefly detached for operations in the Jordan Valley and Transjordan,[19] consisted of

- Anzac Mounted Division

- 1st Light Horse Brigade (Brigadier General C. F. Cox)

- 1st, 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Regiments

- 2nd Light Horse Brigade (Brigadier General G. de L. Ryrie)

- 5th, 6th and 7th Light Horse Regiments

- New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade (Brigadier General W. Meldrum)

- Auckland, Canterbury and Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiments

- 18th Brigade RHA

- Inverness-shire, Ayrshire and Somerset Batteries, RHA and Divisional Ammunition Column

- A/263 Battery RFA

- 195th Heavy Battery RGA

- 29th and 32nd Indian Mountain Batteries

- No. 6 (Medium) Trench Mortar Battery

- 3 anti–aircraft sections RA

- Detachment No. 35 AT Company RE

- 1st Light Horse Brigade (Brigadier General C. F. Cox)

- 20th Indian Brigade

- 110th Mahratta Light Infantry

- Alwar Infantry (I.S.)

- 4th Battalion, Gwalior Infantry (I.S.)

- 1st Battalion, Patiala Infantry (I.S.) (Rajindra Sikhs)

- Attached

See also

- Military history of Australia during World War I

- Military history of New Zealand during World War I

- For more on the Desert Mounted Corps Memorial, see Mount Clarence, Western Australia and the Mounted Memorial, Canberra

References

Footnotes

- At the time of the First World War, the modern Turkish state did not exist, and instead it was part of the Ottoman Empire. While the terms have distinct historical meanings, within many English-language sources the term "Turkey" and "Ottoman Empire" are used synonymously, although many academic sources differ in their approach.[2] The sources used in this article predominately use the term "Turkey". There is also a WP:CONSENSUS to use Turkish the full discussion and rational can be seen at Wikipedia talk:WikiProject Military history/Archive 122#Ottoman Turkish Empire wording dispute.

- Originally called the Imperial Mounted Division.[13]

- The Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade was also in Egypt, but it was designated as Army Troops under army command.[14]

- The Camel Corps Brigade was slightly different with four battalions each with an establishment of 770 men.[16]

- Being mounted rifleman the light horse regiments were not issued cavalry swords and during the charge had to use their bayonets instead.[47]

- Allenby gives the totals as about 2,000 prisoners, 500 dead and thirteen guns. While Powles claims it was fifty-eight officers, 1090 other ranks, ten field guns, and four machine guns.[49][50]

- Powles claims the charge captured thirty prisoners, eleven artillery guns and four machine guns.[64]

Citations

- "Informal group portrait of headquarters staff of the Desert Mounted Corps". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Fewster, Basarin, Basarin, 2003, pp.xi–xii

- Mortlock 2010, p.3

- Powles 1922, p.122

- Woodward 2006, p.4

- Preston 1921, p.1

- Gullett 1941, p.354

- Preston 1921, p.7

- Powles 1922, p.12

- Preston 1921, pp.8–9

- Bou 2009, p.166

- Preston 1921 p. viii

- Powles 1922, p.108

- Preston 1921, p.8

- Preston 1921, p.168

- "Imperial Camel Corps organization". New Zealand History. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Powles 1922, p.3

- Preston 1920, p.154

- "No. 31767". The London Gazette (Supplement). 3 February 1920. p. 1529.

- "Imperial Camel Corps". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- Hill 1978 p. 116

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 357

- Keogh 1955 pp. 125–6

- Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 357, Vol. 2 pp. 661–2

- Wavell 1968 pp. 190–1

- Hughes 2004 p. 35

- Erickson 2007 pp. 112–3

- Grainger 2006 pp. 239–40

- Allenby to Robertson 12 July 1917 in Hughes 2004 p. 35

- Cutlack 1941 pp. 63–4

- Hill 1978 p. 118

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 16

- Powles 1922, p. 128

- Preston 1921, p. 11

- Preston 1921, p.12

- Preston 1921, pp. 12–13

- Powles 1922, p. 135

- Preston 1921, p.13

- Gullett 1941, p.375

- Preston 1921, p.17

- Preston 1921, pp.23–24

- Preston 1921, p.24

- Preston 1921, p.25

- Preston 1921, p.26

- Preston 1921, p.27

- Preston 1921, pp.28–29

- Preston 1921, p.29

- Preston 1921, p.30

- "No. 30492". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 January 1918. p. 1189.

- Powles 1922, p.139

- Preston 1921, p.31

- Preston 1921, p.32

- Preston 1921, pp.32–33

- Preston 1921, pp.38–39

- Preston 1921, p.43

- Preston 1921, p.44

- Preston 1921, pp.45–46

- Preston 1921, p.48

- Preston 1921, pp.50–51

- Preston 1921, p.51

- Preston 1921, p.53

- Powles 1922, p.143

- "No. 30492". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 January 1918. p. 1191.

- Powles 1922, p.144

- Preston 1921, p.54

- Preston 1921, p.56

- Preston 1921, p.52

- Preston 1921, p.58

- Preston 1921, p.59

- Preston 1921, p.60

- Preston 1921, p.61

- Preston 1921, p.62

- Preston 1921, pp.64–65

- Preston 1921, p.65

- Preston 1921, p.66

- Preston 1921, pp.68–69

- Preston 1921, p.69

- Preston 1921, p.71

- Preston 1921, pp.72–73

- Preston 1921, p.74

- Preston 1921, p.77

- Preston 1921, pp.78–79

- Preston 1921, p.79

- Preston 1921, p.80

- Preston 1921, pp.82–84

- Preston 1921, p.84

- Preston 1921, p.85

- Preston 1921, p.86

- Preston 1921, p.88

- Powles 1922, p.151

- Preston 1921, p.89

- Preston 1921, pp.90–91

- Preston 1921, p.92

- Preston 1921, pp.93–94

- Preston 1921, p.101

- Preston 1921, p.102

- Preston 1921, p.105

- Preston 1921, p.106

- Preston 1921, p.108

- Preston 1921, p.109

- Preston 1921, pp. 110–114

- Preston 1921, p.115

- Preston 1921, p.121

- Preston 1920, p.122

- Preston 1920, pp.128–129

- Preston 1920, pp.132–133

- Preston 1920, p.133

- Preston 1920, pp.135–136

- Preston 1920, pp.136–137

- Preston 1920, p.137

- Preston 1920, pp.138–139

- Preston 1920, p.139

- Preston 1920, p.140

- Preston 1920, pp.141–142

- Preston 1920, p.142

- Preston 1920, p.144

- Preston 1920, p.146

- Preston 1920, p.147

- Preston 1920, p.148

- Preston 1920, pp.149–150

- Preston 1920, p.151

- Preston 1920, p.153

- Preston 1920, p.155

- Preston 1920, p.157–158

- Preston 1920, p.158–159

- Preston 1920, p.160

- Preston 1920, p.161–162

- Preston 1920, p.162–163

- Preston 1920, p.164

- Preston 1920, p.166

- Preston 1920, pp.166–167

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 660

- Preston 1921, p.331

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 661

- Preston 1921, p.332

- Preston 1921, p.333

- Preston 1921, p.334

- Jones 1987, pp. 146–7

- Preston 1921, p. 335

- Massey 1920, p. 338

- Keogh 1955, p. 240

- Powles 1922, p. 236

- Wavell 1968, p. 219

- Massey 1920, p. 339

- Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. 673

Bibliography

- Bou, Jean (2009). Light Horse: A History of Australia's Mounted Arm. Australian Army History Series. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521197083.

- Falls, Cyril (1996) [1930]. Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from the Outbreak of War with Germany to June 1917. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. Nashville, TN: HMSO. ISBN 1-870423-60-7.

- Fewster, Kevin; Basarin, Vecihi; Basarin, Hatice Hurmuz (2003). Gallipoli: The Turkish Story. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-045-5.

- Fleming, Robert (2012). The Australian Army in World War I. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 9781780964577.

- Gullett, Henry S. (1941). The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. VII (10th ed.). ISBN 9780702217265.

- Jones, Ian (2007). A Thousand Miles of Battle: The Saga of the Australian Light Horse in WWI. Aspley, Queensland: Anzac Day Commemoration Committee. OCLC 27150826.

- Keogh, E. G.; Joan Graham (1955). Suez to Aleppo. Melbourne: Directorate of Military Training by Wilkie & Co. OCLC 220029983.

- Macmunn, G.; Falls, C. (1996) [1928 HMSO]. Military Operations: Egypt and Palestine, From the Outbreak of War with Germany to June 1917. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I. Nashville, TN: Imperial War Museum & Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-241-1.

- Massey, William Thomas (1920). Allenby's Final Triumph. London: Constable. OCLC 345306.

- Mortlock, Michael J. (2010). The Egyptian Expeditionary Force in World War I: A History of the British-Led Campaigns in Egypt, Palestine and Syria. McFarland. ISBN 9780786448715.

- Powles, C. Guy; A. Wilkie (1922). The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine. Official History New Zealand's Effort in the Great War. Vol. III. Auckland: Whitcombe & Tombs. OCLC 2959465.

- Powles, Charles Guy (1922). The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine. Whitcombe and Tombs. ISBN 9781843426530.

- Preston, Richard Martin (1921). The Desert Mounted Corps: An Account of the Cavalry Operations in Palestine and Syria, 1917–1918. London: Constable. ISBN 9781146758833.

- Wavell, Field Marshal Earl (1968) [1933]. "The Palestine Campaigns". In Sheppard, Eric William (ed.). A Short History of the British Army (4th ed.). London: Constable. OCLC 35621223.

- Woodward, David R. (2006). Hell in the Holy Land: World War I in the Middle East. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813123837.