Sumatran rhinoceros

The Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), also known as the Sumatran rhino, hairy rhinoceros or Asian two-horned rhinoceros, is a rare member of the family Rhinocerotidae and one of five extant species of rhinoceros; it is the only extant species of the genus Dicerorhinus. It is the smallest rhinoceros, although it is still a large mammal; it stands 112–145 cm (44–57 in) high at the shoulder, with a head-and-body length of 2.36–3.18 m (7 ft 9 in – 10 ft 5 in) and a tail of 35–70 cm (14–28 in). The weight is reported to range from 500–1,000 kg (1,100–2,200 lb), averaging 700–800 kg (1,500–1,800 lb). Like both African species, it has two horns; the larger is the nasal horn, typically 15–25 cm (5.9–9.8 in), while the other horn is typically a stub. A coat of reddish-brown hair covers most of the Sumatran rhino's body.

| Sumatran rhinoceros Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sumatran rhinoceros at Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary in Lampung, Indonesia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genus: | Dicerorhinus |

| Species: | D. sumatrensis[2] |

| Binomial name | |

| Dicerorhinus sumatrensis[2] | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

Current Sumatran rhinoceros range | |

The Sumatran rhinoceros once inhabited rainforests, swamps and cloud forests in India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and southwestern China, particularly in Sichuan.[4][5] It is now critically endangered, with only five substantial populations in the wild: four in Sumatra and one in Borneo, with an estimated total population of fewer than 80 mature individuals.[6][7] The species was extirpated in Malaysia in 2019, and one of the Sumatran populations may already be extinct. In 2015, researchers announced that the Bornean rhinoceros had become extinct in the northern part of Borneo in Sabah, Malaysia.[8] A tiny population was discovered in East Kalimantan in early 2016.[9]

The Sumatran rhino is a mostly solitary animal except for courtship and offspring-rearing. It is the most vocal rhino species and also communicates through marking soil with its feet, twisting saplings into patterns, and leaving excrement. The species is much better studied than the similarly reclusive Javan rhinoceros, in part because of a program that brought 40 Sumatran rhinos into captivity with the goal of preserving the species. There was little or no information about procedures that would assist in ex situ breeding. Though a number of rhinos died once at the various destinations and no offspring were produced for nearly 20 years, the rhinos were all doomed in their soon-to-be-logged forest.[10] In March 2016, a Sumatran rhinoceros (of the Bornean rhinoceros subspecies) was spotted in Indonesian Borneo.[11]

The Indonesian ministry of Environment, began an official counting of the Sumatran rhino in February 2019, planned to be completed in three years.[12] Malaysia's last known bull and cow Sumatran rhinos died in May and November 2019, respectively. The species is now considered to be locally extinct in that country, and only survives in Indonesia. There are fewer than 80 left in existence.[13]

Taxonomy and naming

The first documented Sumatran rhinoceros was shot 16 km (9.9 mi) outside Fort Marlborough, near the west coast of Sumatra, in 1793. Drawings of the animal, and a written description, were sent to the naturalist Joseph Banks, then president of the Royal Society of London, who published a paper on the specimen that year.[14] In 1814, the species was given a scientific name by Johann Fischer von Waldheim.[15][16]

The specific epithet sumatrensis signifies "of Sumatra", the Indonesian island where the rhinos were first discovered.[17] Carl Linnaeus originally classified all rhinos in the genus, Rhinoceros; therefore, the species was originally identified as Rhinoceros sumatrensis or sumatranus.[18] Joshua Brookes considered the Sumatran rhinoceros with its two horns a distinct genus from the one-horned Rhinoceros, and gave it the name Didermocerus in 1828. Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger proposed the name Dicerorhinus in 1841. In 1868, John Edward Gray proposed the name Ceratorhinus. Normally, the oldest name would be used, but a 1977 ruling by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature established the proper genus name as Dicerorhinus.[3][19] Dicerorhinus comes from the Greek terms di (δι, meaning "two"), cero (κέρας, meaning "horn"), and rhinos (ρινος, meaning "nose").[20]

The three subspecies are:

D. s. sumatrensis, known as the western Sumatran rhinoceros, which has only 75 to 85 rhinos remaining, mostly in the national parks of Bukit Barisan Selatan and Kerinci Seblat, Gunung Leuser in Sumatra, but also in Way Kambas National Park in small numbers.[1] They have recently gone extinct in Peninsular Malaysia. The main threats against this subspecies are habitat loss and poaching. A slight genetic difference is noted between the western Sumatran and Bornean rhinos.[1] The rhinos in Peninsular Malaysia were once known as D. s. niger, but were later recognized to be a synonym of D. s. sumatrensis.[3] Three bulls and five cows currently live in captivity at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary at Way Kambas, the youngest bull having been bred and born there in 2012.[21] Another calf, a female, was born at the sanctuary in May 2016.[22] The sanctuary's two bulls were born at the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden.[23] A third calf female was born in March 2022.

D. s. harrissoni, known as the Bornean rhinoceros or eastern Sumatran rhinoceros, which was once common throughout Borneo; now only about 15 individuals are estimated to survive.[9] The known population lives in East Kalimantan, with them having recently gone extinct in Sabah.[24] Reports of animals surviving in Sarawak are unconfirmed.[1] This subspecies is named after Tom Harrisson, who worked extensively with Bornean zoology and anthropology in the 1960s.[25] The Bornean subspecies is markedly smaller in body size than the other two subspecies.[3] The captive population consisted of one bull and two cows at the Borneo Rhinoceros Sanctuary in Sabah; the bull died in 2019 and the cows died in 2017 and 2019 respectively.[26][27]

D. s. lasiotis, known as the northern Sumatran rhinoceros or Chittagong rhinoceros, which once roamed India and Bangladesh, has been declared extinct in these countries. Unconfirmed reports suggest a small population may still survive in Myanmar, but the political situation in that country has prevented verification.[1] The name lasiotis is derived from the Greek for "hairy-ears". Later studies showed that their ear hair was not longer than other Sumatran rhinos, but D. s. lasiotis remained a subspecies because it was significantly larger than the other subspecies.[3]

Evolution

Ancestral rhinoceroses first diverged from other perissodactyls in the Early Eocene. Mitochondrial DNA comparison suggests the ancestors of modern rhinos split from the ancestors of Equidae around 50 million years ago.[28][29] The extant family, the Rhinocerotidae, first appeared in the Late Eocene in Eurasia, and the ancestors of the extant rhino species dispersed from Asia beginning in the Miocene.[30]

Sumatran rhinoceros is considered the least derived of the extant species, as it shares more traits with its Miocene ancestors.[31]: 13 Paleontological evidence in the fossil record dates the genus Dicerorhinus to the Early Miocene, 23–16 million years ago. Many fossils have been classified as members of Dicerorhinus, but no other recent species are in the genus.[32] Molecular dating suggests the split of Dicerorhinus from the four other extant species as far back as 25.9 ± 1.9 million years. Three hypotheses have been proposed for the relationship between the Sumatran rhinoceros and the other living species. One hypothesis suggests the Sumatran rhinoceros is closely related to the black and white rhinos in Africa, evidenced by the species having two horns, instead of one.[28] Other taxonomists regard the Sumatran rhinoceros as a sister taxon of the Indian and Javan rhinoceros because their ranges overlap so closely.[28][33] A third hypothesis, based on more recent analyses, however, suggests that the two African rhinos, the two Asian rhinos, and the Sumatran rhinoceros represent three essentially separate lineages that split around 25.9 million years ago; which group diverged first remains unclear.[28][34] Recent studies suggest that many specimens attributed to Dicerorhinus from the Pleistocene of China actually belong to Stephanorhinus, a closely related genus.[35] The earliest fossil record of the species is from the Early Pleistocene Liucheng Gigantopithecus Cave in Guangxi, China, which consists of a nearly complete mandible with preserved cheek teeth and various isolated teeth.[36] Fossil material of the Sumatran rhinoceros also found in the Middle Pleistocene of Thailand.[37]

Because of morphological similarities, the Sumatran rhinoceros is believed to be closely related to the extinct woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) and Stephanorhinus. The woolly rhinoceros, so named for the coat of hair it shares with the Sumatran rhinoceros, first appeared in China; by the Upper Pleistocene, it ranged across the Eurasian continent from Korea to Spain. The woolly rhinoceros survived the last ice age, but, like the woolly mammoth, most or all became extinct around 10,000 years ago. Stephanorhinus species are well known in Europe from the Late Pliocene through the Pleistocene, and China from the Pleistocene, with two species, Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis and the Stephanorhinus hemitoechus surviving into the last glacial period. Although some morphological studies questioned the relationship,[34] recent molecular analysis has supported the close relationship.[38]

Pairwise sequential Markovian coalescent (PSMC) analysis of a complete nuclear genome of a Sumatran specimen suggested strong fluctuations in population size, with a general trend of decline over the course of the Middle to Late Pleistocene with an estimated peak effective population size of 57,800 individuals 950,000 years ago, declining to around 500–1,300 individuals at the start of the Holocene, with a slight rebound during the Eemian Interglacial. This was likely due to climate change causing limiting suitable habitat for the Rhinoceros, causing severe population fluctuations as well as population fragmentation due to the flooding of Sundaland. Human induced habitat change and hunting may have played a role in the Late Pleistocene.[39] The study was later criticised for not including DNA from extinct mainland populations, which would have provided a holistic account.[40] A Bayesian skyline plot of complete Mitochondrial genomes from multiple individuals from across the range of the species suggested that the population had been relatively stable with an effective population size of 40,000 individuals over the last 400,000 years, with a sharp decline starting around 25,000 years ago.[41]

Cladogram showing the relationships of recent and Late Pleistocene rhinoceros species (minus Stephanorhinus hemitoechus) based on whole nuclear genomes, after Liu et al, 2021:[42]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

A mature Sumatran rhino stands about 120–145 cm (3.94–4.76 ft) high at the shoulder, has a body length of around 250 cm (8.2 ft), and weighs 500–800 kg (1,100–1,760 lb),[43] though the largest individuals in zoos have been known to weigh as much as 2,000 kg (4,410 lb).[44] Like the two African species, it has two horns. The larger is the nasal horn, typically only 15–25 cm (5.9–9.8 in), though the longest recorded specimen was much longer at 81 cm (32 in).[43] The posterior horn is much smaller, usually less than 10 cm (3.9 in) long, and often little more than a knob. The larger nasal horn is also known as the anterior horn; the smaller posterior horn is known as the frontal horn.[32] The horns are dark grey or black in color. The bulls have larger horns than the cows, though the species is not otherwise sexually dimorphic. The Sumatran rhino lives an estimated 30–45 years in the wild, while the record time in captivity is a female D. lasiotis, which lived for 32 years and 8 months before dying in the London Zoo in 1900.[32]

Two thick folds of skin encircle the body behind the front legs and before the hind legs. The rhino has a smaller fold of skin around its neck. The skin itself is thin, 10–16 mm (0.39–0.63 in), and in the wild, the rhino appears to have no subcutaneous fat. Hair can range from dense (the most dense hair in young calves) to scarce, and is usually a reddish brown. In the wild, this hair is hard to observe because the rhinos are often covered in mud. In captivity, however, the hair grows out and becomes much shaggier, likely because of less abrasion from walking through vegetation. The rhino has a patch of long hair around its ears and a thick clump of hair at the end of its tail. Like all rhinos, they have very poor vision. The Sumatran rhinoceros is fast and agile; it climbs mountains easily and comfortably traverses steep slopes and riverbanks.[17][32][43]

Distribution and habitat

The Sumatran rhinoceros lives in both lowland and highland secondary rainforest, swamps, and cloud forests. It inhabits hilly areas close to water, particularly steep upper valleys with copious undergrowth. The Sumatran rhinoceros once inhabited a continuous range as far north as Myanmar, eastern India, and Bangladesh. Unconfirmed reports also placed it in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. All known living animals occur in the island of Sumatra. Some conservationists hope Sumatran rhinos may still survive in Burma, though it is considered unlikely. Political turmoil in Burma has prevented any assessment or study of possible survivors.[45] The last reports of stray animals from Indian limits were in the 1990s.[46]

The Sumatran rhino is widely scattered across its range, much more so than the other Asian rhinos, which has made it difficult for conservationists to protect members of the species effectively.[45] Only four areas are known to contain Sumatran rhinoceros: Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, Gunung Leuser National Park, and Way Kambas National Park on Sumatra; and on Indonesian Borneo west of Samarindah.[47]

The Kerinci Seblat National Park, Sumatra's largest, was estimated to contain a population of around 500 rhinos in the 1980s,[48] but due to poaching, this population is now considered extinct. The survival of any animals in Peninsular Malaysia is extremely unlikely.[49]

Genetic analysis of Sumatran rhino populations has identified three distinct genetic lineages.[16] The channel between Sumatra and Malaysia was not as significant a barrier for the rhinos as the Barisan Mountains along the length of Sumatra, for rhinos in eastern Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia are more closely related than the rhinos on the other side of the mountains in western Sumatra. In fact, the eastern Sumatra and Malaysia rhinos show so little genetic variance, the populations were likely not separate during the Pleistocene, when sea levels were much lower and Sumatra formed part of the mainland. Both populations of Sumatra and Malaysia, however, are close enough genetically that interbreeding would not be problematic. The rhinos of Borneo are sufficiently distinct that conservation geneticists have advised against crossing their lineages with the other populations.[16] Conservation geneticists have recently begun to study the diversity of the gene pool within these populations by identifying microsatellite loci. The results of initial testing found levels of variability within Sumatran rhino populations comparable to those in the population of the less endangered African rhinos, but the genetic diversity of Sumatran rhinos is an area of continuing study.[50]

Although the rhino had been thought to be extinct in Kalimantan since the 1990s, in March 2013 World Wildlife Fund (WWF) announced that the team when monitoring orangutan activity found in West Kutai Regency, East Kalimantan, several fresh rhino foot trails, mud holes, traces of rhino-rubbed trees, traces of rhino horns on the walls of mud holes, and rhino bites on small branches. The team also identified that rhinos ate more than 30 species of plants.[51] On 2 October 2013, video images made with camera traps showing the Sumatran rhino in Kutai Barat, Kalimantan, were released by the World Wildlife Fund. Experts assume the videos show two different animals, but aren't quite certain. According to the Indonesia's Minister of Forestry, Zulkifli Hasan called the video evidence "very important" and mentioned Indonesia's "target of rhino population growth by three percent per year".[16][52] On 22 March 2016 it was announced by the WWF that a live Sumatran rhino was found in Kalimantan; it was the first contact in over 40 years. The rhino, a female, was captured and transported to a nearby sanctuary to ensure her survival.[53]

Iman, the last known Sumatran rhino in Malaysia, died in November 2019; stem cell technology is being used in an attempt to revitalize the rhino's population and reverse extinction in the country.[54]

Behavior and ecology

Sumatran rhinos are solitary creatures except for pairing before mating and during offspring rearing. Individuals have home ranges; bulls have territories as large as 50 km2 (19 sq mi), whereas cows' ranges are 10–15 km2 (3.9–5.8 sq mi).[17] The ranges of cows appear to be spaced apart; bulls' ranges often overlap. No evidence indicates Sumatran rhinos defend their territories through fighting. Marking their territories is done by scraping soil with their feet, bending saplings into distinctive patterns, and leaving excrement. The Sumatran rhino is usually most active when eating, at dawn, and just after dusk. During the day, they wallow in mud baths to cool down and rest. In the rainy season, they move to higher elevations; in the cooler months, they return to lower areas in their range.[17] When mud holes are unavailable, the rhino will deepen puddles with its feet and horns. The wallowing behaviour helps the rhino maintain its body temperature and protect its skin from ectoparasites and other insects. Captive specimens, deprived of adequate wallowing, have quickly developed broken and inflamed skins, suppurations, eye problems, inflamed nails, and hair loss, and have eventually died. One 20-month study of wallowing behavior found they will visit no more than three wallows at any given time. After two to 12 weeks using a particular wallow, the rhino will abandon it. Typically, the rhino will wallow around midday for two to three hours at a time before venturing out for food. Although in zoos the Sumatran rhino has been observed wallowing less than 45 minutes a day, the study of wild animals found 80–300 minutes (an average of 166 minutes) per day spent in wallows.[56]

There has been little opportunity to study epidemiology in the Sumatran rhinoceros. Ticks and gyrostigma were reported to cause deaths in captive animals in the 19th century.[43] The rhino is also known to be vulnerable to the blood disease surra, which can be spread by horse-flies carrying parasitic trypanosomes; in 2004, all five rhinos at the Sumatran Rhinoceros Conservation Center died over an 18-day period after becoming infected by the disease.[57] The Sumatran rhino has no known predators other than humans. Tigers and wild dogs may be capable of killing a calf, but calves stay close to their mothers, and the frequency of such killings is unknown. Although the rhino's range overlaps with elephants and tapirs, the species do not appear to compete for food or habitat. Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) and Sumatran rhinos are even known to share trails, and many smaller species such as deer, boars, and wild dogs will use the trails the rhinos and elephants create.[17][58]

The Sumatran rhino maintains trails across its range. These trails fall into two types. Main trails will be used by generations of rhinos to travel between important areas in the rhino's range, such as between salt licks, or in corridors through inhospitable terrain that separates ranges. In feeding areas, the rhinos will make smaller trails, still covered by vegetation, to areas containing food the rhino eats. Sumatran rhino trails have been found that cross rivers deeper than 1.5 m (4.9 ft) and about 50 m (160 ft) across. The currents of these rivers are known to be strong, but the rhino is a strong swimmer.[32][43] A relative absence of wallows near rivers in the range of the Sumatran rhinoceros indicates they may occasionally bathe in rivers in lieu of wallowing.[58]

Diet

Most feeding occurs just before nightfall and in the morning. The Sumatran rhino is a folivore,[60] with a diet of young saplings, leaves, twigs, and shoots.[32] The rhinos usually consume up to 50 kg (110 lb) of food a day.[17] Primarily by measuring dung samples, researchers have identified more than 100 food species consumed by the Sumatran rhinoceros. The largest portion of the diet is tree saplings with a trunk diameter of 1–6 cm (0.39–2.36 in). The rhinoceros typically pushes these saplings over with its body, walking over the sapling without stepping on it, to eat the leaves. Many of the plant species the rhino consumes exist in only small portions, which indicates the rhino is frequently changing its diet and feeding in different locations.[58] Among the most common plants the rhino eats are many species from the Euphorbiaceae, Rubiaceae, and Melastomataceae families. The most common species the rhino consumes is Eugenia.[59]

The vegetal diet of the Sumatran rhinoceros is high in fiber and only moderate in protein.[61] Salt licks are very important to the nutrition of the rhino. These licks can be small hot springs, seepages of salty water, or mud-volcanoes. The salt licks also serve an important social purpose for the rhinos—bulls visit the licks to pick up the scent of cows in oestrus. Some Sumatran rhinos, however, live in areas where salt licks are not readily available, or the rhinos have not been observed using the licks. These rhinos may get their necessary mineral requirements by consuming plants rich in minerals.[58][59]

Communication

The Sumatran rhinoceros is the most vocal of the rhinoceros species.[62] Observations of the species in zoos show the animal almost constantly vocalizing, and it is known to do so in the wild, as well.[43] The rhino makes three distinct noises: eeps, whales, and whistle-blows. The eep, a short, one-second-long yelp, is the most common sound. The whale, named for its similarity to vocalizations of the humpback whale, is the most song-like vocalization and the second-most common. The whale varies in pitch and lasts from four to seven seconds. The whistle-blow is named because it consists of a two-second-long whistling noise and a burst of air in immediate succession. The whistle-blow is the loudest of the vocalizations, loud enough to make the iron bars in the zoo enclosure where the rhinos were studied vibrate. The purpose of the vocalizations is unknown, though they are theorized to convey danger, sexual readiness, and location, as do other ungulate vocalizations. The whistle-blow could be heard at a great distance, even in the dense brush in which the Sumatran rhino lives. A vocalization of similar volume from elephants has been shown to carry 9.8 km (6.1 mi) and the whistle-blow may carry as far.[62] The Sumatran rhinoceros will sometimes twist the saplings they do not eat. This twisting behavior is believed to be used as a form of communication, frequently indicating a junction in a trail.[58]

Reproduction

Cows become sexually mature at the age of six to seven years, while bulls become sexually mature at about 10 years old. The gestation period is around 15–16 months. The calf, which typically weighs 40–60 kg (88–132 lb), is weaned after about 15 months and stays with its mother for the first two to three years of its life. In the wild, the birth interval for this species is estimated to be four to five years; its natural offspring-rearing behavior is unstudied.[17]

The reproductive habits of the Sumatran rhinoceros have been studied in captivity. Sex relationships begin with a courtship period characterized by increased vocalization, tail raising, urination, and increased physical contact, with both bull and cow using their snouts to bump the other in the head and genitals. The pattern of courtship is most similar to that of the black rhinoceros. Young Sumatran rhino bulls are often too aggressive with cows, sometimes injuring and even killing them during the courtship. In the wild, the cow could run away from an overly aggressive bull, but in their smaller captive enclosures, they cannot; this inability to escape aggressive bulls may partly contribute to the low success rate of captive-breeding programs.[63][64][65]

The period of oestrus itself, when the cow is receptive to the bull, lasts about 24 hours, and observations have placed its recurrence between 21 and 25 days. Sumatran rhinos in the Cincinnati Zoo have been observed copulating for 30–50 minutes, similar in length to other rhinos; observations at the Sumatran Rhinoceros Conservation Centre in Malaysia have shown a briefer copulation cycle. As the Cincinnati Zoo has had successful pregnancies, and other rhinos also have lengthy copulatory periods, a lengthy rut may be the natural behavior.[63] Though researchers observed successful conceptions, all these pregnancies ended in failure for a variety of reasons until the first successful captive birth in 2001; studies of these failures at the Cincinnati Zoo discovered the Sumatran rhino's ovulation is induced by mating and it had unpredictable progesterone levels.[66] Breeding success was finally achieved in 2001, 2004, and 2007 by providing a pregnant rhino with supplementary progestin.[67] In 2016, a calf was born in captivity in western Indonesia, only the fifth such birth in a breeding facility.[68] In March 2022, and again on 1 October 2023, female calves were born at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary (SRS), Way Kambas National Park, Lampung province, Indonesia.[69][70]

Conservation

In the wild

Sumatran rhinos were once quite numerous throughout Southeast Asia. Fewer than 100 individuals are now estimated to remain.[1][7] The species is classed as critically endangered (primarily due to illegal poaching) while the last survey in 2008 estimated that around 250 individuals survived.[71][72] From the early 1990s, the population decline was estimated at more than 50% per decade, and the small, scattered populations now face high risks of inbreeding depression.[1] Most remaining habitat is in relatively inaccessible mountainous areas of Indonesia.[73][74]

Poaching of Sumatran rhinos is a cause for concern, due to the high market price of its horns.[31]: 31 This species has been overhunted for many centuries, leading to the current greatly reduced and still declining population.[1] The rhinos are difficult to observe and hunt directly (one field researcher spent seven weeks in a treehide near a salt lick without ever observing a rhino directly), so poachers make use of spear traps and pit traps. In the 1970s, uses of the rhinoceros's body parts among the local people of Sumatra were documented, such as the use of rhino horns in amulets and a folk belief that the horns offer some protection against poison. Dried rhinoceros meat was used as medicine for diarrhea, leprosy, and tuberculosis. "Rhino oil", a concoction made from leaving a rhino's skull in coconut oil for several weeks, may be used to treat skin diseases. The extent of use and belief in these practices is not known.[43][45][58] Rhinoceros horn was once believed to be widely used as an aphrodisiac; in fact traditional Chinese medicine never used it for this purpose.[31]: 29 Nevertheless, hunting in this species has primarily been driven by a demand for rhino horns with unproven medicinal properties.[1]

The rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia, which the Sumatran rhino inhabits, are also targets for legal and illegal logging because of the desirability of their hardwoods. Rare woods such as merbau, meranti and semaram are valuable on the international markets, fetching as much as $1,800 per m3 ($1,375 per cu yd). Enforcement of illegal-logging laws is difficult because humans live within or near many of the same forests as the rhino. The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake has been used to justify new logging. Although the hardwoods in the rainforests of the Sumatran rhino are destined for international markets and not widely used in domestic construction, the number of logging permits for these woods has increased dramatically because of the tsunami.[47] However, while this species has been suggested to be highly sensitive to habitat disturbance, apparently it is of little importance compared to hunting, as it can withstand more or less any forest condition.[1] Nevertheless, the main cause of drastic reduction of the species is likely caused by the Allee effect.[75]

The Bornean rhino in Sabah was confirmed to be extinct in the wild in April 2015, with only 3 individuals left in captivity.[76] The mainland Sumatran rhino in Malaysia was confirmed to be extinct in the wild in August 2015.[77] In March 2016 there was a rare sighting of a Sumatran rhino in Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo. The last time there was a Sumatran rhino in the Kalimantan area was approximately 40 years ago. This optimism was met with despair as the same rhino was found dead several weeks after the sighting. The cause of death is unknown.[78]

In captivity

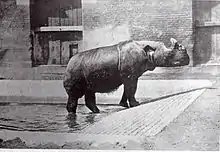

Sumatran rhinos do not thrive outside of their ecosystem. London Zoo acquired a bull and cow in 1872 that had been captured in Chittagong in 1868. The female named "Begum" survived until 1900, the record lifetime for a captive rhino.[79] Begum was one of at least seven specimens of the extinct subspecies D. s. lasiotis that were held in zoos and circuses.[43] In 1972, Subur, the only Sumatran rhino remaining in captivity, died at the Copenhagen Zoo.[43]

Despite the species' persistent lack of reproductive success, in the early 1980s, some conservation organizations began a captive-breeding program for the Sumatran rhinoceros. Between 1984 and 1996, this ex situ conservation program transported 40 Sumatran rhinos from their native habitats to zoos and reserves across the world. While hopes were initially high, and much research was conducted on the captive specimens, by the late 1990s, not a single rhino had been born in the program, and most of its proponents agreed the program had been a failure. In 1997, the IUCN's Asian rhino specialist group, which once endorsed the program, declared it had failed "even maintaining the species within acceptable limits of mortality", noting that, in addition to the lack of births, 20 of the captured rhinos had died.[45] In 2004, a surra outbreak at the Sumatran Rhinoceros Conservation Centre killed all the captive rhinos in Peninsular Malaysia, reducing the population of captive rhinos to eight.[57][74]

Seven of these captive rhinos were sent to the United States, and three to Port Lympne Zoo in the United Kingdom (the other was kept in Southeast Asia), but by 1997, their numbers had dwindled to three: a cow in the Los Angeles Zoo, a bull in the Cincinnati Zoo, and a cow in the Bronx Zoo. In a final effort, the three rhinos were united in Cincinnati. After years of failed attempts, the cow from Los Angeles, Emi, became pregnant for the sixth time, with the zoo's bull Ipuh. All five of her previous pregnancies ended in failure. Reproductive physiologist at the Cincinnati Zoo, Terri Roth, had learned from previous failures, though, and with the aid of special hormone treatments, Emi gave birth to a healthy male calf named Andalas (an Indonesian literary word for Sumatra) in September 2001.[80] Andalas's birth was the first successful captive birth of a Sumatran rhino in 112 years. A female calf, named "Suci" (Indonesian for "pure"), followed on 30 July 2004.[81] On 29 April 2007, Emi gave birth a third time, to her second male calf, named Harapan (Indonesian for "hope") or Harry.[67][82] In 2007, Andalas, who had been living at the Los Angeles Zoo, was returned to Sumatra to take part in breeding programs with healthy females,[65][83] leading to the siring and 23 June 2012 birth of male calf Andatu, the fourth captive-born calf of the era; Andalas had been mated with Ratu, a wild-born cow living in the Rhino Sanctuary at Way Kambas National Park.[84]

Despite the recent successes in Cincinnati, the captive-breeding program has remained controversial. Proponents argue that the zoos have not only aided the conservation effort by studying the reproductive habits, raising public awareness and education about the rhinos, helping raise financial resources for conservation efforts in Sumatra but, moreover, to have established a small captive breeding group.[85] Opponents of the captive breeding program argue that the losses are too great; the program is too expensive; removing rhinos from their habitat, even temporarily, alters their ecological role; and captive populations cannot match the rate of recovery seen in well-protected native habitats.[65] In October 2015, Harapan, the last rhino in the Western Hemisphere, left the Cincinnati Zoo to Indonesia.[86]

In August 2016, there were only three Sumatran rhinos left in Malaysia, all in captivity in the eastern state of Sabah: A bull named Tam and two cows named Puntung and Iman.[87] In June 2017, Puntung was put down due to skin cancer.[88] Tam died on 27 May 2019 and Iman died of cancer on 23 November 2019 at the Borneo Rhino Sanctuary.[89][90][91][92] The species became extinct in Malaysia, its native land in 2019.[93]

In Indonesia, meanwhile, a seventh rhino increased the group at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary, in Way Kambas NP. A female was born on 12 May 2016.[94] Another female, daughter of Andatu and Rosa, was born on 24 March 2022.[95]

Cultural depictions

Aside from those few individuals kept in zoos and pictured in books, the Sumatran rhinoceros has remained little known, overshadowed by the more common Indian, black and white rhinos. Recently, however, video footage of the Sumatran rhinoceros in its native habitat and in breeding centers has been featured in several nature documentaries. Extensive footage can be found in an Asia Geographic documentary The Littlest Rhino. Natural History New Zealand showed footage of a Sumatran rhino, shot by freelance Indonesian-based cameraman Alain Compost, in the 2001 documentary The Forgotten Rhino, which featured mainly Javan and Indian rhinos.[96][97]

Though they were documented by droppings and tracks, pictures of the Bornean rhinoceros were first taken and widely distributed by modern conservationists in April 2006, when camera traps photographed a healthy adult in the jungles of Sabah in Malaysian Borneo.[98] On 24 April 2007, it was announced that cameras had captured the first-ever video footage of a wild Bornean rhino. The night-time footage showed the rhino eating, peering through jungle foliage, and sniffing the film equipment. The World Wildlife Fund, which took the video, has used it in efforts to convince local governments to turn the area into a rhino conservation zone.[99][100] Monitoring has continued; 50 new cameras have been set up, and in February 2010, what appeared to be a pregnant rhino was filmed.[101]

A number of folk tales about the Sumatran rhino were collected by colonial naturalists and hunters from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century. In Burma, the belief was once widespread that the Sumatran rhino ate fire. Tales described the fire-eating rhino following smoke to its source, especially campfires, and then attacking the camp. There was also a Burmese belief that the best time to hunt was every July, when the Sumatran rhinos would congregate beneath the full moon. In Malaya, it was said that the Sumatran rhino's horns was hollow and could be used as a sort of hose for breathing air and squirting water. In Malaya and Sumatra, it was once believed that the rhino shed its horns every year and buried them under the ground. In Borneo, the rhino was said to have a strange carnivorous practice: after defecating in a stream, it would turn around and eat fish that had been stupefied by the excrement.[43]

References

- Ellis, S. & Talukdar, B. (2020). "Dicerorhinus sumatrensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T6553A18493355. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T6553A18493355.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Species Dicerorhinus sumatrensis". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 635. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Rookmaaker, L. C. (1984). "The taxonomic history of the recent forms of Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis)". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 57 (1): 12–25. JSTOR 41492969.

- Chapman, J. (1999). The Art of Rhinoceros Horn Carving in China. London: Christie's Books. p. 27. ISBN 0-903432-57-9.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T'ang Exotics. University of California Press. Berkeley and Los Angeles. p. 83

- "Rhino population figures". SaveTheRhino.org. 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Pusparini, W.; Sievert, P.R.; Fuller, T.K.; Randhir, T.O. & Andayani, N. (2015). "Rhinos in the parks: An island-wide survey of the last wild population of the Sumatran Rhinoceros". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0139982. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1036643P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136643. PMC 4574046. PMID 26376453.

- Havmøller, R.G.; Payne, J.; Ramono, W.; Ellis, S.; Yoganand, K.; Long, B.; Dinerstein, E.; Williams, A.C.; Putra, R.H.; Gawi, J.; Talukdar, B.K. & Burgess, N. (2015). "Will current conservation responses save the Critically Endangered Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis?". Oryx. 50 (2): 355–359. doi:10.1017/S0030605315000472.

- "15 Bornean rhinos discovered in Kalimantan?". Mongabay. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Nardelli, F. 2014 The last chance for the Sumatran rhinoceros?. Pachyderm 55: 43–53 http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/index.php?s=1&act=refs&CODE=ref_detail&id=1411778068

- "Rare Sumatran rhino sighted in Indonesian Borneo". Fox News. 23 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "To rescue Sumatran rhinos, Indonesia starts by counting them first". Mongabay Environmental News. 15 April 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Williams, David; Ko, Stella (24 November 2019). "The last Sumatran rhino in Malaysia has died and there are less than 80 left in the world". CNN. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Banks, J.; Bell, W. (1793). "Description of the Double Horned Rhinoceros of Sumatra". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 83: 3–6. doi:10.1098/rstl.1793.0003.

- Rookmaaker, K. (2005). "First sightings of Asian rhinos". In Fulconis, R. (ed.). Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. London: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. p. 52.

- Morales, J.C.; Andau, P.M.; Supriatna, J.; Zainal-Zahari, Z.; Melnick, D.J. (April 1997). "Mitochondrial DNA Variability and Conservation Genetics of the Sumatran Rhinoceros". Conservation Biology. 11 (2): 539–543. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.96171.x. S2CID 55337818.

- van Strien, N. (2005). "Sumatran rhinoceros". In Fulconis, R. (ed.). Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. London: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. pp. 70–74.

- "Burmah", Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., vol. Vol. IV, 1876, p. p. 552.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1977). "Opinion 1080. Didermocerus Brookes, 1828 (Mammalia) suppressed under the plenary powers". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 34: 21–24.

- Liddell, H.G.; Scott, Robert (1980). Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- International_Rhino_Foundation#Sumatran_Rhino_Sanctuary

- Cota Larson, Rhishja (12 May 2016). "It's a Girl! Critically Endangered Sumatran Rhino Born at Sanctuary in Indonesia". annamiticus.com. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Sheridan, Kerry (22 September 2015). "Critically endangered Sumatran rhino pregnant: conservationists". phys.org. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Hance, Jeremy (23 April 2015). "Officials: Sumatran rhino is extinct in the wild in Sabah". Mongabay. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Groves, C. P. (1965). "Description of a new subspecies of Rhinoceros, from Borneo, Didermocerus sumatrensis harrissoni". Saugetierkundliche Mitteilungen. 13 (3): 128–131.

- Jeremy Hance (23 April 2015), Officials: Sumatran rhino is extinct in the wild in Sabah, Mongabay

- Woodyatt, Amy (27 May 2019). "Malaysia's last male Sumatran rhino dies". CNN. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Tougard, C.; T. Delefosse; C. Hoenni; C. Montgelard (2001). "Phylogenetic relationships of the five extant rhinoceros species (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12s rRNA genes" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 19 (1): 34–44. doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0903. PMID 11286489.

- Xu, Xiufeng; Axel Janke; Ulfur Arnason (1996). "The Complete Mitochondrial DNA Sequence of the Greater Indian Rhinoceros, Rhinoceros unicornis, and the Phylogenetic Relationship Among Carnivora, Perissodactyla, and Artiodactyla (+ Cetacea)". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 13 (9): 1167–1173. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025681. PMID 8896369.

- Lacombat, F. (2005). "The evolution of the rhinoceros". In Fulconis, R. (ed.). Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. London: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. pp. 46–49.

- Dinerstein, Eric (2003). The Return of the Unicorns; The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08450-1.

- Groves, Colin P.; Kurt, Fred (1972). "Dicerorhinus sumatrensis". Mammalian Species. American Society of Mammalogists (21): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503818. JSTOR 3503818.

- Groves, C. P. (1983). "Phylogeny of the living species of rhinoceros" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung. 21 (4): 293–313. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1983.tb00297.x.

- Cerdeño, E. (1995). "Cladistic Analysis of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla)" (PDF). Novitates (3143).

- Tong, H. (2012). "Evolution of the non-Coelodonta dicerorhine lineage in China". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (8): 555–562. Bibcode:2012CRPal..11..555T. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.06.002.

- Tong, H. & Guérin, C. (2009). "Early Pleistocene Dicerorhinus sumatrensis remains from the Liucheng Gigantopithecus Cave, Guangxi, China". Geobios. 42 (4): 525–539. Bibcode:2009Geobi..42..525T. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2009.02.001.

- K. Suraprasit, J.-J. Jaegar, Y. Chaimanee, O. Chavasseau, C. Yamee, P. Tian, and S. Panha (2016). "The Middle Pleistocene vertebrate fauna from Khok Sung (Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand): biochronological and paleobiogeographical implications". ZooKeys (613): 1–157. doi:10.3897/zookeys.613.8309. PMC 5027644. PMID 27667928.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Orlando, L.; Leonard, J.A.; Thenot, A.; Laudet, V.; Guerin, C. & Hänni, C. (2003). "Ancient DNA analysis reveals woolly rhino evolutionary relationships" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 28 (2): 485–499. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00023-X. PMID 12927133.

- Mays, H.L.; Hung, C.-M.; Shaner, P.-J.; Denvir, J.; Justice, M.; Yang, S.-F.; Roth, T.L.; Oehler, D.A.; Fan, J.; Rekulapally, S. & Primerano, D.A. (2018). "Genomic analysis of demographic history and ecological niche modeling in the endangered Sumatran Rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis". Current Biology. 28 (1): 70–76.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.11.021. PMC 5894340. PMID 29249659.

- Lander, B.; Brunson, K. (2018). "The Sumatran rhinoceros was extirpated from mainland East Asia by hunting and habitat loss". Current Biology. 28 (6): R252–R253. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.012. PMID 29558637.

- Steine, C.C.; Houck, M.L. & Ryder, O.A. (2018). "Genetic variation of complete mitochondrial genome sequences of the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis)". Conservation Genetics. 19 (2): 397–408. doi:10.1007/s10592-017-1011-1. S2CID 4301239.

- Liu, S.; Westbury, M.V.; Dussex, N.; Mitchell, K.J.; Sinding, M.-H.S.; Heintzman, P.D.; Duchêne, D.A.; Kapp, J.D.; von Seth, J.; Heiniger, H. & Sánchez-Barreiro, F. (2021). "Ancient and modern genomes unravel the evolutionary history of the rhinoceros family". Cell. 184 (19): 4874–4885.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.032. PMID 34433011. S2CID 237273079.

- van Strien, N. J. (1974). "Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (Fischer), the Sumatran or two-horned rhinoceros: a study of literature". Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen. 74 (16): 1–82.

- Groves, C. P.; Kurt, F. (1972). "Dicerorhinus sumatrenis" (PDF). Mammalian Species (21): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503818. JSTOR 3503818. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2012.

- Foose, Thomas J.; van Strien, Nico (1997). Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 2-8317-0336-0.

- Choudhury, A. U. (1997). "The status of the Sumatran rhinoceros in north-eastern India" (PDF). Oryx. 31 (2): 151–152. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3008.1997.d01-9.x.

- Dean, Cathy; Tom Foose (2005). "Habitat loss". In Fulconis, R. (ed.). Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. London: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. pp. 96–98.

- "Rhino population at Indonesian reserve drops by 90 percent in 14 years". SOS Rhino. 18 March 2012

- "Sumatran rhino numbers revised downwards". Save The Rhino. 18 March 2012.

- Scott, C.; Foose, T.; Morales, J. C.; Fernando, P.; Melnick, D. J.; Boag, P. T.; Davila, J. A.; Van Coeverden de Groot, P. J. (2004). "Optimization of novel polymorphic microsatellites in the endangered Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis)" (PDF). Molecular Ecology Notes. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 4 (2): 194–196. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00611.x.

- "Traces of Sumatran rhino found in Kalimantan". 29 March 2013. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013.

- Erwida Maulia (2 October 2013). "Sumatran Rhino Caught on Camera in East Kalimantan". The Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- "New hope for Sumatran rhino in Borneo". 22 March 2016.

- Jessie Yeung (14 August 2020). "Every Sumatran rhino has died in Malaysia. Scientists want to bring them back with cloning technology". CNN. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- Rookmaaker, L. C. (1998). "London, UK". The rhinoceros in captivity: a list of 2439 rhinoceroses kept from Roman times to 1994. The Hague: Kugler Publications. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-90-5103-134-8.

- Ng, J.S.C.; Zainal-Zahari, Z.; Nordin, A. (2001). "Wallows and wallow utilization of the Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus Sumatrensis) in a natural enclosure in Sungai Dusun Wildlife Reserve, Selangor, Malaysia" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife and Parks. 19: 7–12.

- Mohamad, Aidi; Vellayan, S.; Radcliffe, Robin W.; Lowenstine, Linda J.; Epstein, Jon; Reid, Simon A.; Paglia, Donald E.; Radcliffe, Rolfe M.; Roth, Terri L.; Foose, Thomas J.; Mohamad Khan bin Momin Khan (2006). "Trypanosomiasis (surra) in the captive Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis sumatrensis) in Peninsular Malaysia" (PDF). Proceedings of the Fourth Rhino Keepers Workshop 2005 at Columbus, Ohio.

- Borner, M. (1979). A field study of the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis Fischer, 1814: Ecology and behaviour conservation situation in Sumatra. Zurich: Juris Druck & Verlag. ISBN 3-260-04600-3.

- Lee, Y.H.; Stuebing, R.B.; Ahmad, A.H. (1993). "The mineral content of food plants of the Sumatran Rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) in Danum Valley, Sabah, Malaysia" (PDF). Biotropica. 3 (5): 352–355. doi:10.2307/2388795. JSTOR 2388795.

- Nardelli, F. (2013). "The mega-folivorous mammals of the rainforest: feeding ecology in nature and in a controlled environment: A contribution to their conservation". International Zoo News. 60 (5): 323–339.

- Dierenfeld, E. S.; Kilbourn, A.; Karesh, W.; Bosi, E.; Andau, M.; Alsisto, S. (2006). "Intake, utilization, and composition of browses consumed by the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni) in captivity in Sabah, Malaysia". Zoo Biology. 25 (5): 417–431. doi:10.1002/zoo.20107.

- von Muggenthaler, Elizabeth; Paul Reinhart; Brad Limpany; R. Barton Craft (2003). "Songlike vocalizations from the Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis)" (PDF). Acoustics Research Letters Online. 4 (3): 83. doi:10.1121/1.1588271.

- Zainal Zahari, Z.; Rosnina, Y.; Wahid, H.; Yap, K. C.; Jainudeen, M. R. (2005). "Reproductive behaviour of captive Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis)" (PDF). Animal Reproduction Science. 85 (3–4): 327–335. doi:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.04.041. PMID 15581515.

- Zainal-Zahari, Z.; Rosnina, Y.; Wahid, H.; Jainudeen, M. R. (2002). "Gross Anatomy and Ultrasonographic Images of the Reproductive System of the Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis)" (PDF). Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 31 (6): 350–354. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0264.2002.00416.x. PMID 12693754. S2CID 19009013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2018.

- Roth, Terri L.; Radcliffem, Robin W.; van Strien, Nico J. (2006). "New hope for Sumatran rhino conservation" (PDF). International Zoo News (abridged from Communiqué ed.). 53 (6): 352–353.

- Roth, T. L.; O'Brien, J. K.; McRae, M. A.; Bellem, A. C.; Romo, S. J.; Kroll, J. L.; Brown, J. L. (2001). "Ultrasound and endocrine evaluation of the ovarian cycle and early pregnancy in the Sumatran rhinoceros, Dicerorhinus sumatrensis" (PDF). Reproduction. 121 (1): 139–149. doi:10.1530/rep.0.1210139. hdl:10088/324. PMID 11226037.

- Roth, T. L. (2003). "Breeding the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) in captivity: behavioral challenges, hormonal solutions" (PDF). Hormones and Behavior. 44: 31. doi:10.1016/S0018-506X(03)00068-0. S2CID 54311703.

- "Sumatran rhino birth hailed as major boost for the critically endangered species". ABC News. 14 May 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "'Happy news' as endangered Sumatran rhino, the smallest and hairiest species, is born in Indonesia". ABC News. 2 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- Budiman, Budisantoso (14 June 2022). "Mengenali nama-nama badak bercula dua di Taman Nasional Way Kambas". ANTARA News Lampung (in Indonesian). Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- "Last chance for the Sumatran rhino". IUCN. 4 April 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- "Sumatran rhino population plunges, down to 100 animals". News.mongabay.com. 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Rabinowitz, A. (1995). "Helping a species go extinct: the Sumatran Rhino in Borneo" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 9 (3): 482–488. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.09030482.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2014.

- van Strien, N. J. (2001). "Conservation programs for Sumatran and Javan Rhino in Indonesia and Malaysia". In Schwammer, H.N.; Foose, T.J.; Fouraker, M.; Olson, D. (eds.). Proceedings of the International Elephant and Rhino Research Symposium, Vienna, 7–11 June 2001. Scientific Progress Reports.

- Payne J. 2016. https://wildtech.mongabay.com/2016/01/reproductive-technology-and-understanding-of-experimental-psychology-needed-to-save-a-critically-endangered-rhino/

- Hance, J. (2015). "Officials: Sumatran rhino is extinct in the wild in Sabah". Mongabay. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Officials:Sumatran rhino now extinct in Malaysian wild". Free Malaysia Today. 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- "Sumatran rhino dies weeks after rare sighting". CNN. 6 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- Lydekker, Richard (1900). The great and small game of India, Burma, and Tibet. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1162-7.

- "Andalas – A Living Legacy". Cincinnati Zoo. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- "It's a Girl! Cincinnati Zoo's Sumatran Rhino Makes History with Second Calf". Cincinnati Zoo. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- "Meet "Harry" the Sumatran Rhino!". Cincinnati Zoo. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- Watson, Paul (26 April 2007). "Come into my mud pool". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- "Rare baby Sumatra rhinoceros named a 'gift from God'". Jakarta Globe. Agence France-Presse. 26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Nardelli F. 2016. Do we really want to save the Sumatran rhinoceros? (commentary). mongabay.com April 2016 http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/index.php?s=1&act=refs&CODE=ref_detail&id=1469019235

- US-born endangered Sumatran rhino arrives in ancestral home of Indonesia on mating mission. Associated Press. (1 November 2015)

- "Only three Sumatran Rhino left in Malaysia". New Straits Times. 26 August 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "Puntung euthanised leaves Malaysia with just two Sumatran rhinos". The Malay Mail Online. 4 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- "Malaysia's last Sumatran rhino Iman dies, species now extinct in the country". Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Malaysia's last male Sumatran rhino Tam dies". The Malay Mail Online. 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Malaysia's last known Sumatran rhino dies". 23 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Last male Sumatran rhino in Malaysia dies". Animals. 27 May 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "Sumatran rhinos are extinct in their native Malaysia after last living female dies". 23 November 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Rare Sumatran rhino calf born in Indonesia". phys.org.

- "A story of hope | Sumatran rhino born | News". Save The Rhino. 28 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- "The Littlest Rhino". Asia Geographic. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- "The Forgotten Rhino". NHNZ. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- "Rhinos alive and well in the final frontier". New Straits Times (Malaysia). 2 July 2006.

- "Rhino on camera was rare sub-species: wildlife group". Agence France Presse. 25 April 2007.

- Video of the Sumatran rhinoceros is available at "Asian rhinos". World Wildlife Fund.

- "Endangered pregnant Borneo rhino caught on camera". The Telegraph. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 24 April 2010.