Stephanorhinus

Stephanorhinus is an extinct genus of two-horned rhinoceros native to Eurasia and North Africa that lived during the Late Pliocene to Late Pleistocene. Species of Stephanorhinus were the predominant and often only species of rhinoceros in much of temperate Eurasia, especially Europe, for most of the Pleistocene. The last two species of Stephanorhinus – Merck's rhinoceros (S. kirchbergensis) and the narrow-nosed rhinoceros (S. hemitoechus) – went extinct during the last glacial period.

| Stephanorhinus Temporal range: Late Pliocene to Late Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stephanorhinus etruscus skeleton | |

_(16144915223).jpg.webp) | |

| Stephanorhinus hundsheimensis skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Tribe: | Dicerorhinini |

| Genus: | †Stephanorhinus Kretzoi, 1942 |

| Type species | |

| †Rhinoceros etruscus Falconer, 1868 | |

| Species | |

| |

Etymology

The first part of the name, Stephano-, honours Stephen I, the first king of Hungary.[1] (The genus name was coined by Kretzoi, a Hungarian.) The second part is from rhinos (Greek for "nose"), a typical suffix of rhinoceros genus names.

Taxonomy

The taxonomic history of Stephanorhinus is long and convoluted, as many species are known by numerous synonyms and different genera – typically Rhinoceros and Dicerorhinus – for the 19th and most of the early 20th century. The genus was named by Miklós Kretzoi in 1942.[2] It is thought that Stephanorhinus is more closely related to the Sumatran rhinoceros and woolly rhinoceros than to all other living rhino species. A complete mitochondrial genome of S. kirchbergensis obtained from a 70,000–48,000-year-old skull preserved in permafrost in arctic Yakutia showed that it was more closely related to the woolly rhinoceros than the Sumatran rhinoceros, with the three species forming a clade to the exclusion of other living rhinoceros species.[3] In 2019 a study of dental proteomes proposed that Stephanorhinius was paraphyletic as currently defined, with the proteome sequence obtained from the enamel of a 1.77 million year old Stephanorhinus tooth from Dmanisi belonging to an indeterminate species found outside the clade containing the woolly rhinoceros and S. kirchbergensis, with the authors positing that the genus Coelodonta was derived from an early diverging lineage within Stephanorhinus.[4] A 2021 study based on nuclear genomes including those of S. kirchbergensis found the same result as the mitochondrial genome study, with strong support, with the estimated split between the woolly rhinoceros and S. kirchbergensis occurring around 5.5 million years ago, with their closest living relatives being Dicerorhinus.[5] A 2023 morphological study recovered Stephanorhinus as monophyletic.[6]

Placement of Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis among recent and subfossil rhinoceros species based on nuclear genomes (Liu, 2021):[5]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bayesian morphological phylogeny (Pandolfi, 2023) Note: This excludes living African rhinoceros species.[6]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Species and evolution

The oldest known species of the genus are from the Pliocene of Europe, the species "S." pikermiensis and "S." megarhinus that were formerly considered to belong to Stephanorhinus are currently considered to belong to Dihoplus, and/or Pliorhinus in the case of "S." megarhinus[7][8][9] while the positions of “Stephanorhinus” miguelcrusafonti from the Early Pliocene of Western Europe and Stephanorhinus? africanus from the Middle Pliocene of Tunisia and Chad are uncertain,[10] with "S.” miguelcrusafonti also having assigned to Pliorhinus in recent studies.[8] Some authors have suggested that Stephanorhinus likely originated from members of the genus Pliorhinus.[6]

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti, also known as S. elatus[11] is known from the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene of Europe. Its remains are relatively rare in comparison to other Stephanorhinus species. Specimens are known from the Late Pliocene of Germany,[12] France, Italy,[13] Slovakia[14] and Greece,[15] and the Early Pleistocene of Romania,[16] with its temporal span being around 3.4 to 2 million years ago.[6]

Stephanorhinus etruscus first appears in the latest Pliocene in the Iberian Peninsula, around 3.3 million years ago (Ma) at Las Higueruelas in Spain and before 3 Ma at Piedrabuena, and during the latest Pliocene at Villafranca d’Asti and Castelnuovo di Berardenga in Italy and is abundant during most of the Villafranchian period in Europe, and is the sole rhinoceros species in Europe between 2.5 and around 1.3 Ma. A specimen is known from the Early Pleistocene (1.6-1.2 Ma) Ubeidiya locality in Israel. During the late Early Pleistocene, it is largely replaced by S. hundsheimensis. The last known records of the species are from the latest Early Pleistocene of the Iberian peninsula, around 0.9-0.8 Ma.[17] Stephanorhinus etruscus is thought to have had a browsing based diet.[18]

Stephanorhinus migrated from its origin in western Eurasia into eastern Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene.[6] Stephanorhinus yunchuchenensis is known from a single specimen in probably late Early Pleistocene aged deposits in Yushe, Shaanxi, China, while Stephanorhinus lantianensis is also known from a single specimen from late Early Pleistocene (1.15 Ma) deposits in Lantian, also in Shaanxi.[19] These may be synonymous with other named Stephanorhinus species, with a 2022 study suggesting that they were likely synonyms of S. kirchbergensis and S. etruscus respectively.[20]

The first definitive record of Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Merck's rhinoceros) is in China at Zhoukoudian (Choukoutien; near Beijing), around the Early–Mid-Pleistocene transition at 0.8 Ma.[19]

Stephanorhinus hundsheimensis first definitively appears in the fossil record in Europe and Anatolia at around 1.2 Ma, with possible records in Iberia around 1.6 Ma and 1.4-1.3 Ma. The earliest confirmed appearance in Italy around 1 Ma.[21] The diet of S. hundsheimensis was flexible and ungeneralised, with two different early Middle Pleistocene populations under different climatic regimes (having tooth wear analyses suggesting contrasting browsing and grazing habits).[22] The more specialised S. kirchbergensis and S. hemitoechus, appear in Europe between 0.7-6 Ma and 0.6-0.5 Ma respectively, and replace S. hundsheimensis. S. kirchbergensis and S. hemitoechus are typically interpreted mixed feeders tending towards browsing and grazing, respectively. The evolution of more specialized diets is possibly due to the change to the 100 Kyr cycle after the Mid-Pleistocene Transition, which resulted in environmental stability allowing the development of more specialized forms.[23]

From the late Middle Pleistocene onwards, the large Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis and Stephanorhinus hemitoechus (each estimated at 2 t (4,400 lb) and 1.6 t (3,500 lb) in weight, respectively[24]) were the only species of Stephanorhinus. S. kirchbergensis was broadly distributed over northern Eurasia from Western Europe to East Asia and the Russian Far East, while S. hemitoechus was generally confined to the western Palearctic, including Europe and North Africa.[25][26][10]

In Europe, S. kirchbergensis disappeared during the earliest Late Pleistocene.[25] The last records of S. hemitoechus in Italy date to around 41,000 years ago.[27] A late record of S. hemitoechus is known from 40,000 years ago in Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria.[28] Remains of S. kirchbergensis in the Russian Far East and South China are suggested to date to marine isotope stage 3 (~60-27,000 years ago) and 2 (~29-14,000 years ago), respectively.[29][30]

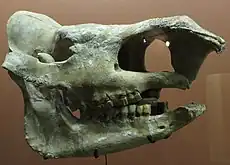

Skull of Stephanorhinus jeanvireti

Skull of Stephanorhinus jeanvireti Skull of Stephanorhinus etruscus

Skull of Stephanorhinus etruscus Skull of Stephanorhinus hundsheimensis

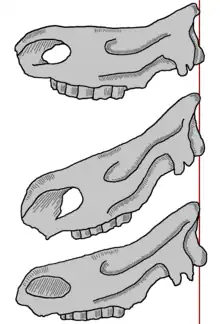

Skull of Stephanorhinus hundsheimensis Skulls from top to bottom. S. kirchbergensis, S. hemitoechus and the woolly rhinoceros, showing the difference in head angle

Skulls from top to bottom. S. kirchbergensis, S. hemitoechus and the woolly rhinoceros, showing the difference in head angle Drawing of Stephanorhinus hemitoechus

Drawing of Stephanorhinus hemitoechus

Relationship with humans

Remains of several Stephanorhinus species, including S. kirchbergensis and S. hemitoechus, have been found in sites across Europe with break or cut marks indicating that they were butchered by archaic humans.[31][32][33][34][35]

References

- Tong, HaoWen; Wu, XianZhu (April 2010). "Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) from the Rhino Cave in Shennongjia, Hubei". Chinese Science Bulletin. 55 (12): 1157–1168. Bibcode:2010ChSBu..55.1157T. doi:10.1007/s11434-010-0050-5. ISSN 1001-6538. S2CID 67828905.

- Miklós Kretzoi: Bemerkungen zur System der Nachmiozänen Nashorn-Gattungen (Comments on the system of the post Miocene rhinoceros genera) Földtani Közlöni, Budapest 72 (4-12), 1942, S. 309–318

- Kirillova, Irina V.; Chernova, Olga F.; van der Made, Jan; Kukarskih, Vladimir V.; Shapiro, Beth; van der Plicht, Johannes; Shidlovskiy, Fedor K.; Heintzman, Peter D.; van Kolfschoten, Thijs; Zanina, Oksana G. (November 2017). "Discovery of the skull of Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Jäger, 1839) above the Arctic Circle". Quaternary Research. 88 (3): 537–550. Bibcode:2017QuRes..88..537K. doi:10.1017/qua.2017.53. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 45478220.

- Cappellini, Enrico; Welker, Frido; Pandolfi, Luca; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Samodova, Diana; Rüther, Patrick L.; Fotakis, Anna K.; Lyon, David; Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Bukhsianidze, Maia; et al. (October 2019). "Early Pleistocene enamel proteome from Dmanisi resolves Stephanorhinus phylogeny". Nature. 574 (7776): 103–107. Bibcode:2019Natur.574..103C. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1555-y. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 6894936. PMID 31511700.

- Liu, Shanlin; Westbury, Michael V.; Dussex, Nicolas; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Heintzman, Peter D.; Duchêne, David A.; Kapp, Joshua D.; von Seth, Johanna; Heiniger, Holly; Sánchez-Barreiro, Fátima (August 2021). "Ancient and modern genomes unravel the evolutionary history of the rhinoceros family". Cell. 184 (19): 4874–4885.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.032. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 34433011. S2CID 237273079.

- Pandolfi, Luca (2023-01-19). "Reassessing the phylogeny of Quaternary Eurasian Rhinocerotidae". Journal of Quaternary Science: jqs.3496. doi:10.1002/jqs.3496. ISSN 0267-8179.

- Pandolfi, Luca; Rivals, Florent; Rabinovich, Rivka (January 2020). "A new species of rhinoceros from the site of Bethlehem: 'Dihoplus' bethlehemsis sp. nov. (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae)". Quaternary International. 537: 48–60. Bibcode:2020QuInt.537...48P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.01.011. S2CID 213080180.

- Pandolfi, Luca; Sendra, Joaquín; Reolid, Matías; Rook, Lorenzo (June 2022). "New Pliocene Rhinocerotidae findings from the Iberian Peninsula and the revision of the Spanish Pliocene records". PalZ. 96 (2): 343–354. doi:10.1007/s12542-022-00607-9. ISSN 0031-0220.

- Pandolfi, Luca; Pierre-Olivier, Antoine; Bukhsianidze, Maia; Lordkipanidze, David; Rook, Lorenzo (2021-08-03). "Northern Eurasian rhinocerotines (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) by the Pliocene–Pleistocene transition: phylogeny and historical biogeography". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 19 (15): 1031–1057. doi:10.1080/14772019.2021.1995907. ISSN 1477-2019.

- Pandolfi, Luca (2018), "Evolutionary history of Rhinocerotina (Mammalia, Perissodactyla)", Fossilia - Reports in Palaeontology, Saverio Bartolini Lucenti, pp. 27–32, doi:10.32774/fosreppal.20.1810.102732, ISBN 979-12-200-3408-1

- Ballatore, Manuel; Breda, Marzia (December 2016). "Stephanorhinus elatus (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia): proposal for the conservation of the earlier specific name and designation of a lectotype". Geodiversitas. 38 (4): 579–594. doi:10.5252/g2016n4a7. ISSN 1280-9659. S2CID 90370988.

- Lacombat, Frédéric; Mörs, Thomas (2008-08-01). "The northernmost occurrence of the rare Late Pliocene rhinoceros Stephanorhinus jeanvireti (Mammalia, Perissodactyla)". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 249 (2): 157–165. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2008/0249-0157.

- Pandolfi, Luca (October 2013). "New and revised occurrences of Dihoplus megarhinus (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) in the Pliocene of Italy". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 132 (2): 239–255. doi:10.1007/s13358-013-0056-0. ISSN 1664-2376. S2CID 140547755.

- Šujan, M., Rybár, S., Šarinová, K., Kováč, M., Vlačiky, M., Zervanová, J., 2013. Uppermost Miocene to Quaternary accumulation history at the Danube Basin eastern flanks, in: Fodor, L., Kövér, Sz. (eds.), 11th Meeting of the Central European Tectonic Studies Group (CETeG). Abstract book, Geol. Geophys. Inst. of Hungary, Budapest, pp. 66-68.

- Guérin, Claude; Tsoukala, Evangelia (June 2013). "The Tapiridae, Rhinocerotidae and Suidae (Mammalia) of the Early Villafranchian site of Milia (Grevena, Macedonia, Greece)". Geodiversitas. 35 (2): 447–489. doi:10.5252/g2013n2a7. ISSN 1280-9659. S2CID 129164720.

- Pandolfi, Luca; Codrea, Vlad A.; Popescu, Aurelian (December 2019). "Stephanorhinus jeanvireti (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) from the early Pleistocene of Colțești (southwestern Romania)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 18 (8): 1041–1056. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2019.07.004.

- Pandolfi, Luca; Cerdeño, Esperanza; Codrea, Vlad; Kotsakis, Tassos (September 2017). "Biogeography and chronology of the Eurasian extinct rhinoceros Stephanorhinus etruscus (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 16 (7): 762–773. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.06.004.

- Pandolfi, Luca; Bartolini-Lucenti, Saverio; Cirilli, Omar; Bukhsianidze, Maia; Lordkipanidze, David; Rook, Lorenzo (July 2021). "Paleoecology, biochronology, and paleobiogeography of Eurasian Rhinocerotidae during the Early Pleistocene: The contribution of the fossil material from Dmanisi (Georgia, Southern Caucasus)". Journal of Human Evolution. 156: 103013. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2021.103013.

- Tong, Hao-wen (November 2012). "Evolution of the non-Coelodonta dicerorhine lineage in China". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (8): 555–562. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.06.002.

- Pandolfi, Luca (December 2022). "A critical overview on Early Pleistocene Eurasian Stephanorhinus (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae): Implications for taxonomy and paleobiogeography". Quaternary International: S1040618222003780. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2022.11.008.

- Pandolfi, Luca; Erten, Hüseyin (January 2017). "Stephanorhinus hundsheimensis (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) from the late early Pleistocene deposits of the Denizli Basin (Anatolia, Turkey)". Geobios. 50 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2016.10.002.

- Kahlke, Ralf-Dietrich; Kaiser, Thomas M. (August 2011). "Generalism as a subsistence strategy: advantages and limitations of the highly flexible feeding traits of Pleistocene Stephanorhinus hundsheimensis (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (17–18): 2250–2261. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.2250K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.12.012.

- van Asperen, Eline N.; Kahlke, Ralf-Dietrich (January 2015). "Dietary variation and overlap in Central and Northwest European Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis and S. hemitoechus (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) influenced by habitat diversity" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 107: 47–61. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.10.001. S2CID 83801422.

- Hans-Dieter Sues, Ross D.E. MacPhee (June 30, 1999). Extinctions in Near Time. Causes, Contexts, and Consequences. Springer US. p. 262. ISBN 9780306460920. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- Diana Pushkina: The Pleistocene easternmost distribution in Eurasia of the species associated with the Eemian Palaeoloxodon antiquus assemblage. Mammal Review, 2007. Volume 37 Issue 3, Pages 224 - 245

- Pierre Olivier Antoine: Pleistocene and holocene rhinocerotids (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Indochinese Peninsula. In: Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2011, S. 1–10.

- PANDOLFI, LUCA; BOSCATO, PAOLO; CREZZINI, JACOPO; GATTA, MAURIZIO; MORONI, ADRIANA; ROLFO, MARIO; TAGLIACOZZO, ANTONIO (2017-04-13). "LATE PLEISTOCENE LAST OCCURRENCES OF THE NARROW-NOSED RHINOCEROS STEPHANORHINUS HEMITOECHUS (MAMMALIA, PERISSODACTYLA) IN ITALY". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia (Research in Paleontology and Stratigraphy). 123: N. 2 (2017). doi:10.13130/2039-4942/8300.

- Stuart, A.J., Lister, A.M., 2007. Patterns of Late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions in Europe and northern Asia. In: Kahlke, R.-D., Maul, L.C., Mazza, P. (Eds.), Late Neogene and Quaternary Biodiversity and Evolution: Regional Developments and Interregional Correlations Vol. II, Proceedings of the 18th International Senckenberg Conference (VI International Palaeontological Colloquium in Weimar). Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 259, pp. 287-297.

- Kosintsev, P. A.; Zykov, S. V.; Tiunov, M. P.; Shpansky, A. V.; Gasilin, V. V.; Gimranov, D. O.; Devjashin, M. M. (March 2020). "The First Find of Merck's Rhinoceros (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae, Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis Jäger, 1839) Remains in the Russian Far East". Doklady Biological Sciences. 491 (1): 47–49. doi:10.1134/S0012496620010032. ISSN 0012-4966. PMID 32483707. S2CID 219156923.

- Pang, Libo; Chen, Shaokun; Huang, Wanbo; Wu, Yan; Wei, Guangbiao (April 2017). "Paleoenvironmental and chronological analysis of the mammalian fauna from Migong Cave in the Three Gorges Area, China". Quaternary International. 434: 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.11.039.

- Bratlund, B. 1999. Taubach revisited. Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 46: 61-174.

- Berruti, Gabriele Luigi Francesco; Arzarello, Marta; Ceresa, Allison; Muttillo, Brunella; Peretto, Carlo (December 2020). "Use-Wear Analysis of the Lithic Industry of the Lower Palaeolithic Site of Guado San Nicola (Isernia, Central Italy)". Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology. 3 (4): 794–815. doi:10.1007/s41982-020-00056-3. ISSN 2520-8217.

- Chen, Xi; Moigne, Anne-Marie (November 2018). "Rhinoceros ( Stephanorhinus hemitoechus ) exploitation in Level F at the Caune de l'Arago (Tautavel, Pyrénéés-Orientales, France) during MIS 12". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 28 (6): 669–680. doi:10.1002/oa.2682. S2CID 80923883.

- Baquedano, Enrique; Arsuaga, Juan L.; Pérez-González, Alfredo; Laplana, César; Márquez, Belén; Huguet, Rosa; Gómez-Soler, Sandra; Villaescusa, Lucía; Galindo-Pellicena, M. Ángeles; Rodríguez, Laura; García-González, Rebeca; Ortega, M.-Cruz; Martín-Perea, David M.; Ortega, Ana I.; Hernández-Vivanco, Lucía (March 2023). "A symbolic Neanderthal accumulation of large herbivore crania". Nature Human Behaviour. 7 (3): 342–352. doi:10.1038/s41562-022-01503-7. ISSN 2397-3374. PMC 10038806. PMID 36702939.

- Smith, Geoff M. (October 2013). "Taphonomic resolution and hominin subsistence behaviour in the Lower Palaeolithic: differing data scales and interpretive frameworks at Boxgrove and Swanscombe (UK)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (10): 3754–3767. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.05.002.