Diffusion of innovations

Diffusion of innovations is a theory that seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread. The theory was popularized by Everett Rogers in his book Diffusion of Innovations, first published in 1962.[1] Rogers argues that diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated over time among the participants in a social system. The origins of the diffusion of innovations theory are varied and span multiple disciplines.

Rogers proposes that five main elements influence the spread of a new idea: the innovation itself, adopters, communication channels, time, and a social system. This process relies heavily on social capital. The innovation must be widely adopted in order to self-sustain. Within the rate of adoption, there is a point at which an innovation reaches critical mass. In 1989, management consultants working at the consulting firm Regis Mckenna Inc. theorized that this point lies at the boundary between the early adopters and the early majority. This gap between niche appeal and mass (self-sustained) adoption was originally labeled "the marketing chasm"[2]

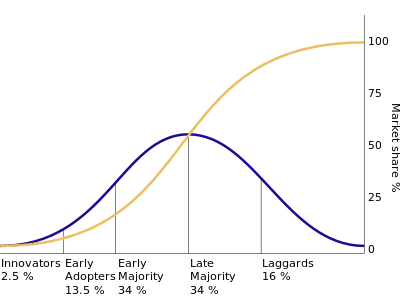

The categories of adopters are innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.[3] Diffusion manifests itself in different ways and is highly subject to the type of adopters and innovation-decision process. The criterion for the adopter categorization is innovativeness, defined as the degree to which an individual adopts a new idea.

History

The concept of diffusion was first studied by the French sociologist Gabriel Tarde in late 19th century[4] and by German and Austrian anthropologists and geographers such as Friedrich Ratzel and Leo Frobenius. The study of diffusion of innovations took off in the subfield of rural sociology in the midwestern United States in the 1920s and 1930s. Agriculture technology was advancing rapidly, and researchers started to examine how independent farmers were adopting hybrid seeds, equipment, and techniques.[5] A study of the adoption of hybrid corn seed in Iowa by Ryan and Gross (1943) solidified the prior work on diffusion into a distinct paradigm that would be cited consistently in the future.[5][6] Since its start in rural sociology, Diffusion of Innovations has been applied to numerous contexts, including medical sociology, communications, marketing, development studies, health promotion, organizational studies, knowledge management, conservation biology[7] and complexity studies,[8] with a particularly large impact on the use of medicines, medical techniques, and health communications.[9] In organizational studies, its basic epidemiological or internal-influence form was formulated by H. Earl Pemberton,[10][11] such as postage stamps and standardized school ethics codes.

In 1962, Everett Rogers, a professor of rural sociology at Ohio State University, published his seminal work: Diffusion of Innovations. Rogers synthesized research from over 508 diffusion studies across the fields that initially influenced the theory: anthropology, early sociology, rural sociology, education, industrial sociology and medical sociology. Rogers applied it to the healthcare setting to address issues with hygiene, cancer prevention, family planning, and drunk driving. Using his synthesis, Rogers produced a theory of the adoption of innovations among individuals and organizations.[12] Diffusion of Innovations and Rogers' later books are among the most often cited in diffusion research. His methodologies are closely followed in recent diffusion research, even as the field has expanded into, and been influenced by, other methodological disciplines such as social network analysis and communication.[13][14]

Elements

The key elements in diffusion research are:

| Element | Definition |

|---|---|

| Innovation | Innovation is a broad category, relative to the current knowledge of the analyzed unit. Any idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption could be considered an innovation available for study.[15] |

| Adopters | Adopters are the minimal unit of analysis. In most studies, adopters are individuals, but can also be organizations (businesses, schools, hospitals, etc.), clusters within social networks, or countries.[16] |

| Communication channels | Diffusion, by definition, takes place among people or organizations. Communication channels allow the transfer of information from one unit to the other.[17] Communication patterns or capabilities must be established between parties as a minimum for diffusion to occur.[18] |

| Time | The passage of time is necessary for innovations to be adopted; they are rarely adopted instantaneously. In fact, in the Ryan and Gross (1943) study on hybrid corn adoption, adoption occurred over more than ten years, and most farmers only dedicated a fraction on their fields to the new corn in the first years after adoption.[6][19] |

| Social system | The social system is the combination of external influences (mass media, surfactants, organizational or governmental mandates) and internal influences (strong and weak social relationships, distance from opinion leaders).[20] There are many roles in a social system, and their combination represents the total influences on a potential adopter.[21] |

Characteristics of innovations

Studies have explored many characteristics of innovations. Meta-reviews have identified several characteristics that are common among most studies.[22] These are in line with the characteristics that Rogers initially cited in his reviews.[23]

Rogers describes five characteristics that potential adopters evaluate when deciding whether to adopt an innovation:[23]

- Compatibility: How well does this innovation fit with existing values, patterns of behavior, or tools?

- Trialability: Can you try it before you buy it?

- Relative advantage: In what way is this innovation better than the alternatives?

- Observability: Are its benefits noticeable? If someone else is using the innovation, can I see it being used?

- Simplicity / Complexity: The easier it is to learn or grasp, the faster it diffuses.

These qualities interact and are judged as a whole. For example, an innovation might be extremely complex, reducing its likelihood to be adopted and diffused, but it might be very compatible with a large advantage relative to current tools. Even with this high learning curve, potential adopters might adopt the innovation anyway.

Studies also identify other characteristics of innovations, but these are not as common as the ones that Rogers lists above.[24] The fuzziness of the boundaries of the innovation can impact its adoption. Specifically, innovations with a small core and large periphery are easier to adopt.[25] Innovations that are less risky are easier to adopt as the potential loss from failed integration is lower.[26] Innovations that are disruptive to routine tasks, even when they bring a large relative advantage, might not be adopted because of added instability. Likewise, innovations that make tasks easier are likely to be adopted.[27] Closely related to relative complexity, knowledge requirements are the ability barrier to use presented by the difficulty to use the innovation. Even when there are high knowledge requirements, support from prior adopters or other sources can increase the chances for adoption.[28]

Characteristics of individual adopters

Like innovations, adopters have been determined to have traits that affect their likelihood to adopt an innovation. A bevy of individual personality traits have been explored for their impacts on adoption, but with little agreement.[29] Ability and motivation, which vary on situation unlike personality traits, have a large impact on a potential adopter's likelihood to adopt an innovation. Unsurprisingly, potential adopters who are motivated to adopt an innovation are likely to make the adjustments needed to adopt it.[30] Motivation can be impacted by the meaning that an innovation holds; innovations can have symbolic value that encourage (or discourage) adoption.[31] First proposed by Ryan and Gross (1943), the overall connectedness of a potential adopter to the broad community represented by a city.[6] Potential adopters who frequent metropolitan areas are more likely to adopt an innovation. Finally, potential adopters who have the power or agency to create change, particularly in organizations, are more likely to adopt an innovation than someone with less power over his choices.[32]

Complementary to the diffusion framework, behavioral models such as Technology acceptance model (TAM) and Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) are frequently used to understand individual technology adoption decisions in greater details.

Characteristics of organizations

Organizations face more complex adoption possibilities because organizations are both the aggregate of its individuals and its own system with a set of procedures and norms.[33] Three organizational characteristics match well with the individual characteristics above: tension for change (motivation and ability), innovation-system fit (compatibility), and assessment of implications (observability). Organizations can feel pressured by a tension for change. If the organization's situation is untenable, it will be motivated to adopt an innovation to change its fortunes. This tension often plays out among its individual members. Innovations that match the organization's pre-existing system require fewer coincidental changes and are easy to assess and more likely to be adopted.[34] The wider environment of the organization, often an industry, community, or economy, exerts pressures on the organization, too. Where an innovation is diffusing through the organization's environment for any reason, the organization is more likely to adopt it.[26] Innovations that are intentionally spread, including by political mandate or directive, are also likely to diffuse quickly.[35][36]

Unlike individual decisions where behavioral models (e.g. TAM and UTAUT) can be used to complement the diffusion framework and reveal further details, these models are not directly applicable to organizational decisions. However, research suggested that simple behavioral models can still be used as a good predictor of organizational technology adoption when proper initial screening procedures are introduced.[37]

Process

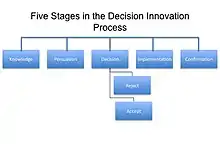

Diffusion occurs through a five–step decision-making process. It occurs through a series of communication channels over a period of time among the members of a similar social system. Ryan and Gross first identified adoption as a process in 1943.[38] Rogers' five stages (steps): awareness, interest, evaluation, trial, and adoption are integral to this theory. An individual might reject an innovation at any time during or after the adoption process. Abrahamson examined this process critically by posing questions such as: How do technically inefficient innovations diffuse and what impedes technically efficient innovations from catching on? Abrahamson makes suggestions for how organizational scientists can more comprehensively evaluate the spread of innovations.[39] In later editions of Diffusion of Innovation, Rogers changes his terminology of the five stages to: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation. However, the descriptions of the categories have remained similar throughout the editions.

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| Knowledge / Awareness | The individual is first exposed to an innovation, but lacks information about the innovation. During this stage the individual has not yet been inspired to find out more information about the innovation. |

| Persuasion | The individual is interested in the innovation and actively seeks related information/details. |

| Decision | The individual takes the concept of the change and weighs the advantages/disadvantages of using the innovation and decides whether to adopt or reject the innovation. Due to the individualistic nature of this stage, Rogers notes that it is the most difficult stage on which to acquire empirical evidence.[12] |

| Implementation | The individual employs the innovation to a varying degree depending on the situation. During this stage the individual also determines the usefulness of the innovation and may search for further information about it. |

| Confirmation / Continuation | The individual finalizes their decision to continue using the innovation. This stage is both intrapersonal (may cause cognitive dissonance) and interpersonal, confirmation the group has made the right decision. This stage allows the adopter to seek reassurance that the decision and implementation are beneficial. Adopters typically experience cognitive dissonance without this final confirmation. Dissonance could be heightened by negative information about the innovation, and if dissonance is not relieved, the innovation may be discounted to restore balance. Change agents help adopters in this stage feel comfortable with their decision. |

Decisions

Two factors determine what type a particular decision is:

- Whether the decision is made freely and implemented voluntarily

- Who makes the decision

Based on these considerations, three types of innovation-decisions have been identified.[40]

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Optional Innovation-Decision | made by an individual who is in some way distinguished from others. |

| Collective Innovation-Decision | made collectively by all participants. |

| Authority Innovation-Decision | made for the entire social system by individuals in positions of influence or power. |

Rate of adoption

The rate of adoption is defined as the relative speed at which participants adopt an innovation. Rate is usually measured by the length of time required for a certain percentage of the members of a social system to adopt an innovation.[41] The rates of adoption for innovations are determined by an individual's adopter category. In general, individuals who first adopt an innovation require a shorter adoption period (adoption process) when compared to late adopters.

Within the adoption curve at some point the innovation reaches critical mass. This is when the number of individual adopters ensures that the innovation is self-sustaining.

Adoption strategies

Rogers outlines several strategies in order to help an innovation reach this stage, including when an innovation adopted by a highly respected individual within a social network and creating an instinctive desire for a specific innovation. Another strategy includes injecting an innovation into a group of individuals who would readily use said technology, as well as providing positive reactions and benefits for early adopters.

Diffusion vis-à-vis adoption

Adoption is an individual process detailing the series of stages one undergoes from first hearing about a product to finally adopting it. Diffusion signifies a group phenomenon, which suggests how an innovation spreads.

Adopter categories

Rogers defines an adopter category as a classification of individuals within a social system on the basis of innovativeness. In the book Diffusion of Innovations, Rogers suggests a total of five categories of adopters in order to standardize the usage of adopter categories in diffusion research. The adoption of an innovation follows an S curve when plotted over a length of time.[42] The categories of adopters are: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards[3] In addition to the gatekeepers and opinion leaders who exist within a given community, change agents may come from outside the community. Change agents bring innovations to new communities– first through the gatekeepers, then through the opinion leaders, and so on through the community.

| Adopter category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Innovators | Innovators are willing to take risks, have the highest social status, have financial liquidity, are social and have closest contact to scientific sources and interaction with other innovators. Their risk tolerance allows them to adopt technologies that may ultimately fail. Financial resources help absorb these failures.[43] |

| Early adopters | These individuals have the highest degree of opinion leadership among the adopter categories. Early adopters have a higher social status, financial liquidity, advanced education and are more socially forward than late adopters. They are more discreet in adoption choices than innovators. They use judicious choice of adoption to help them maintain a central communication position.[44] |

| Early Majority | They adopt an innovation after a varying degree of time that is significantly longer than the innovators and early adopters. Early Majority have above average social status, contact with early adopters and seldom hold positions of opinion leadership in a system (Rogers 1962, p. 283) |

| Late Majority | They adopt an innovation after the average participant. These individuals approach an innovation with a high degree of skepticism and after the majority of society has adopted the innovation. Late Majority are typically skeptical about an innovation, have below average social status, little financial liquidity, in contact with others in late majority and early majority and little opinion leadership. |

| Laggards | They are the last to adopt an innovation. Unlike some of the previous categories, individuals in this category show little to no opinion leadership. These individuals typically have an aversion to change-agents. Laggards typically tend to be focused on "traditions", lowest social status, lowest financial liquidity, oldest among adopters, and in contact with only family and close friends. |

Failed diffusion

Failed diffusion does not mean that the technology was adopted by no one. Rather, failed diffusion often refers to diffusion that does not reach or approach 100% adoption due to its own weaknesses, competition from other innovations, or simply a lack of awareness. From a social networks perspective, a failed diffusion might be widely adopted within certain clusters but fail to make an impact on more distantly related people. Networks that are over-connected might suffer from a rigidity that prevents the changes an innovation might bring, as well.[45][46] Sometimes, some innovations also fail as a result of lack of local involvement and community participation.

For example, Rogers discussed a situation in Peru involving the implementation of boiling drinking water to improve health and wellness levels in the village of Los Molinas. The residents had no knowledge of the link between sanitation and illness. The campaign worked with the villagers to try to teach them to boil water, burn their garbage, install latrines and report cases of illness to local health agencies. In Los Molinas, a stigma was linked to boiled water as something that only the "unwell" consumed, and thus, the idea of healthy residents boiling water prior to consumption was frowned upon. The two-year educational campaign was considered to be largely unsuccessful. This failure exemplified the importance of the roles of the communication channels that are involved in such a campaign for social change. An examination of diffusion in El Salvador determined that there can be more than one social network at play as innovations are communicated. One network carries information and the other carries influence. While people might hear of an innovation's uses, in Rogers' Los Molinas sanitation case, a network of influence and status prevented adoption.[47][48]

Heterophily and communication channels

Lazarsfeld and Merton first called attention to the principles of homophily and its opposite, heterophily. Using their definition, Rogers defines homophily as "the degree to which pairs of individuals who interact are similar in certain attributes, such as beliefs, education, social status, and the like".[49] When given the choice, individuals usually choose to interact with someone similar to themselves. Homophilous individuals engage in more effective communication because their similarities lead to greater knowledge gain as well as attitude or behavior change. As a result, homophilous people tend to promote diffusion among each other.[50] However, diffusion requires a certain degree of heterophily to introduce new ideas into a relationship; if two individuals are identical, no diffusion occurs because there is no new information to exchange. Therefore, an ideal situation would involve potential adopters who are homophilous in every way, except in knowledge of the innovation.[51]

Promotion of healthy behavior provides an example of the balance required of homophily and heterophily. People tend to be close to others of similar health status.[52] As a result, people with unhealthy behaviors like smoking and obesity are less likely to encounter information and behaviors that encourage good health. This presents a critical challenge for health communications, as ties between heterophilous people are relatively weaker, harder to create, and harder to maintain.[53] Developing heterophilous ties to unhealthy communities can increase the effectiveness of the diffusion of good health behaviors. Once one previously homophilous tie adopts the behavior or innovation, the other members of that group are more likely to adopt it, too.[54]

The role of social systems

Opinion leaders

Not all individuals exert an equal amount of influence over others. In this sense opinion leaders are influential in spreading either positive or negative information about an innovation. Rogers relies on the ideas of Katz & Lazarsfeld and the two-step flow theory in developing his ideas on the influence of opinion leaders.[55]

Opinion leaders have the most influence during the evaluation stage of the innovation-decision process and on late adopters.[56] In addition opinion leaders typically have greater exposure to the mass media, more cosmopolitan, greater contact with change agents, more social experience and exposure, higher socioeconomic status, and are more innovative than others.

Research was done in the early 1950s at the University of Chicago attempting to assess the cost-effectiveness of broadcast advertising on the diffusion of new products and services.[57] The findings were that opinion leadership tended to be organized into a hierarchy within a society, with each level in the hierarchy having most influence over other members in the same level, and on those in the next level below it. The lowest levels were generally larger in numbers and tended to coincide with various demographic attributes that might be targeted by mass advertising. However, it found that direct word of mouth and example were far more influential than broadcast messages, which were only effective if they reinforced the direct influences. This led to the conclusion that advertising was best targeted, if possible, on those next in line to adopt, and not on those not yet reached by the chain of influence.

Research on actor-network theory (ANT) also identifies a significant overlap between the ANT concepts and the diffusion of innovation which examine the characteristics of innovation and its context among various interested parties within a social system to assemble a network or system which implements innovation.[58]

Other research relating the concept to public choice theory finds that the hierarchy of influence for innovations need not, and likely does not, coincide with hierarchies of official, political, or economic status.[59] Elites are often not innovators, and innovations may have to be introduced by outsiders and propagated up a hierarchy to the top decision makers.

Electronic communication social networks

Prior to the introduction of the Internet, it was argued that social networks had a crucial role in the diffusion of innovation particularly tacit knowledge in the book The IRG Solution – hierarchical incompetence and how to overcome it.[60] The book argued that the widespread adoption of computer networks of individuals would lead to much better diffusion of innovations, with greater understanding of their possible shortcomings and the identification of needed innovations that would not have otherwise occurred. The social model proposed by Ryan and Gross[38] is expanded by Valente who uses social networks as a basis for adopter categorization instead of solely relying on the system-level analysis used by Ryan and Gross. Valente also looks at an individual's personal network, which is a different application than the organizational perspective espoused by many other scholars.[61]

Recent research by Wear shows, that particularly in regional and rural areas, significantly more innovation takes place in communities which have stronger inter-personal networks.[62]

Organizations

Innovations are often adopted by organizations through two types of innovation-decisions: collective innovation decisions and authority innovation decisions. The collective decision occurs when adoption is by consensus. The authority decision occurs by adoption among very few individuals with high positions of power within an organization.[63] Unlike the optional innovation decision process, these decision processes only occur within an organization or hierarchical group. Research indicated that, with proper initial screening procedures, even simple behavioral model can serve as a good predictor for technology adoption in many commercial organizations.[37] Within an organization certain individuals are termed "champions" who stand behind an innovation and break through opposition. The champion plays a very similar role as the champion used within the efficiency business model Six Sigma. The process contains five stages that are slightly similar to the innovation-decision process that individuals undertake. These stages are: agenda-setting, matching, redefining/restructuring, clarifying and routinizing.

Extensions of the theory

Policy

Diffusion of Innovations has been applied beyond its original domains. In the case of political science and administration, policy diffusion focuses on how institutional innovations are adopted by other institutions, at the local, state, or country level. An alternative term is 'policy transfer' where the focus is more on the agents of diffusion and the diffusion of policy knowledge, such as in the work of Diane Stone.[64] Specifically, policy transfer can be defined as "knowledge about how policies administrative arrangements, institutions, and ideas in one political setting (past or present) is used in the development of policies, administrative arrangements, institutions, and ideas in another political setting".[65]

The first interests with regards to policy diffusion were focused in time variation or state lottery adoption,[66] but more recently interest has shifted towards mechanisms (emulation, learning and coercion)[67][68] or in channels of diffusion[69] where researchers find that regulatory agency creation is transmitted by country and sector channels. At the local level, examining popular city-level policies make it easy to find patterns in diffusion through measuring public awareness.[70] At the international level, economic policies have been thought to transfer among countries according to local politicians' learning of successes and failures elsewhere and outside mandates made by global financial organizations.[71] As a group of countries succeed with a set of policies, others follow, as exemplified by the deregulation and liberalization across the developing world after the successes of the Asian Tigers. The reintroduction of regulations in the early 2000s also shows this learning process, which would fit under the stages of knowledge and decision, can be seen as lessons learned by following China's successful growth.[72]

Technology

Peres, Muller and Mahajan suggested that diffusion is "the process of the market penetration of new products and services that is driven by social influences, which include all interdependencies among consumers that affect various market players with or without their explicit knowledge".[73]

Eveland evaluated diffusion from a phenomenological view, stating, "Technology is information, and exists only to the degree that people can put it into practice and use it to achieve values".[74]

Diffusion of existing technologies has been measured using "S curves". These technologies include radio, television, VCR, cable, flush toilet, clothes washer, refrigerator, home ownership, air conditioning, dishwasher, electrified households, telephone, cordless phone, cellular phone, per capita airline miles, personal computer and the Internet. These data[75] can act as a predictor for future innovations.

Diffusion curves for infrastructure[76] reveal contrasts in the diffusion process of personal technologies versus infrastructure.

Consequences of adoption

Both positive and negative outcomes are possible when an individual or organization chooses to adopt a particular innovation. Rogers states that this area needs further research because of the biased positive attitude that is associated with innovation.[77] Rogers lists three categories for consequences: desirable vs. undesirable, direct vs. indirect, and anticipated vs. unanticipated.

In contrast Wejnert details two categories: public vs. private and benefits vs. costs.[78]

Public vis-à-vis private

Public consequences comprise the impact of an innovation on those other than the actor, while private consequences refer to the impact on the actor. Public consequences usually involve collective actors, such as countries, states, organizations or social movements. The results are usually concerned with issues of societal well-being. Private consequences usually involve individuals or small collective entities, such as a community. The innovations are usually concerned with the improvement of quality of life or the reform of organizational or social structures.[79]

Benefits vis-à-vis costs

Benefits of an innovation obviously are the positive consequences, while the costs are the negative. Costs may be monetary or nonmonetary, direct or indirect. Direct costs are usually related to financial uncertainty and the economic state of the actor. Indirect costs are more difficult to identify. An example would be the need to buy a new kind of pesticide to use innovative seeds. Indirect costs may also be social, such as social conflict caused by innovation.[79] Marketers are particularly interested in the diffusion process as it determines the success or failure of a new product. It is quite important for a marketer to understand the diffusion process so as to ensure proper management of the spread of a new product or service.

Intended vis-à-vis Unintended

The diffusion of innovations theory has been used to conduct research on the unintended consequences of new interventions in public health. In the book multiple examples of the unintended negative consequences of technological diffusion are given. The adoption of automatic tomato pickers developed by Midwest agricultural colleges led to the adoption of harder tomatoes (disliked by consumers) and the loss of thousands of jobs leading to the collapse of thousands of small farmers. In another example, the adoption of snowmobiles in Saami reindeer herding culture is found to lead to the collapse of their society with widespread alcoholism and unemployment for the herders, ill-health for the reindeer (such as stress ulcers, miscarriages) and a huge increase in inequality.

Mathematical treatment

The diffusion of an innovation typically follows an S shaped curve which often resembles a logistic function. Roger's diffusion model concludes that the popularity of a new product will grow with time to a saturation level and then decline, but it cannot predict how much time it will take and what the saturation level will be. Bass (1969)[80] and many other researchers proposed modeling the diffusion based on parametric formulas to fill this gap and to provide a means for a quantitative forecast of adoption timing and levels. The Bass model focuses on the first two (Introduction and Growth). Some of the Bass-Model extensions present mathematical models for the last two (Maturity and Decline). MS-Excel or other tools can be used to solve the Bass model equations, and other diffusion models equations, numerically. Mathematical programming models such as the S-D model apply the diffusion of innovations theory to real data problems.[81] In addition to that, agent-based models follow a more intuitive process by designing individual-level rules to model the diffusion of ideas and innovations.[82]

Complex systems models

Complex network models can also be used to investigate the spread of innovations among individuals connected to each other by a network of peer-to-peer influences, such as in a physical community or neighborhood.[83]

Such models represent a system of individuals as nodes in a network (or graph). The interactions that link these individuals are represented by the edges of the network and can be based on the probability or strength of social connections. In the dynamics of such models, each node is assigned a current state, indicating whether or not the individual has adopted the innovation, and model equations describe the evolution of these states over time.[84]

In threshold models,[85] the uptake of technologies is determined by the balance of two factors: the (perceived) usefulness (sometimes called utility) of the innovation to the individual as well as barriers to adoption, such as cost. The multiple parameters that influence decisions to adopt, both individual and socially motivated, can be represented by such models as a series of nodes and connections that represent real relationships. Borrowing from social network analysis, each node is an innovator, an adopter, or a potential adopter. Potential adopters have a threshold, which is a fraction of his neighbors who adopt the innovation that must be reached before he will adopt. Over time, each potential adopter views his neighbors and decides whether he should adopt based on the technologies they are using. When the effect of each individual node is analyzed along with its influence over the entire network, the expected level of adoption was seen to depend on the number of initial adopters and the network's structure and properties. Two factors emerge as important to successful spread of the innovation: the number of connections of nodes with their neighbors and the presence of a high degree of common connections in the network (quantified by the clustering coefficient). These models are particularly good at showing the impact of opinion leaders relative to others.[86] Computer models are often used to investigate this balance between the social aspects of diffusion and perceived intrinsic benefit to the individuals.[87]

Criticism

Even though there have been more than four thousand articles across many disciplines published on Diffusion of Innovations, with a vast majority written after Rogers created a systematic theory, there have been few widely adopted changes to the theory.[8] Although each study applies the theory in slightly different ways, this lack of cohesion has left the theory stagnant and difficult to apply with consistency to new problems.[88][89]

Diffusion is difficult to quantify because humans and human networks are complex. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to measure what exactly causes adoption of an innovation.[90] This is important, particularly in healthcare. Those encouraging adoption of health behaviors or new medical technologies need to be aware of the many forces acting on an individual and his or her decision to adopt a new behavior or technology. Diffusion theories can never account for all variables, and therefore might miss critical predictors of adoption.[91] This variety of variables has also led to inconsistent results in research, reducing heuristic value.[92]

Rogers placed the contributions and criticisms of diffusion research into four categories: pro-innovation bias, individual-blame bias, recall problem, and issues of equality. The pro-innovation bias, in particular, implies that all innovation is positive and that all innovations should be adopted.[1] Cultural traditions and beliefs can be consumed by another culture's through diffusion, which can impose significant costs on a group of people.[92] The one-way information flow, from sender to receiver, is another weakness of this theory. The message sender has a goal to persuade the receiver, and there is little to no reverse flow. The person implementing the change controls the direction and outcome of the campaign. In some cases, this is the best approach, but other cases require a more participatory approach.[93] In complex environments where the adopter is receiving information from many sources and is returning feedback to the sender, a one-way model is insufficient and multiple communication flows need to be examined.[94]

See also

- Collaborative innovation network

- Critical mass (sociodynamics)

- Delphi technique

- Frugal innovation

- Hierarchical organization

- Information revolution

- Lateral communication

- Lateral diffusion

- Lazy user model

- Memetics

- Opinion leadership

- Pace of innovation

- Pro-innovation bias

- Public choice theory

- Sociological theory of diffusion

- Tacit knowledge

- Technological revolution

- The Wisdom of Crowds

References

- Stone, Diane (January 2004). "Transfer agents and global networks in the 'transnationalization' of policy" (PDF). Journal of European Public Policy (Submitted manuscript). 11 (3): 545–566. doi:10.1080/13501760410001694291. S2CID 153837868.

- Stone, Diane (January 2000). "Non-governmental policy transfer: the strategies of independent policy institutes". Governance. 13 (1): 45–70. doi:10.1111/0952-1895.00123.

- Stone, Diane (February 1999). "Learning lessons and transferring policy across time, space and disciplines". Politics. 19 (1): 51–59. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.00086. S2CID 143819195.

- Noel, Hayden (2009). Consumer behaviour. Lausanne, Switzerland La Vergne, TN: AVA Academia Distributed in the USA by Ingram Publisher Services. ISBN 9782940439249.

- Loudon, David L.; Bitta, Albert J. Della (1993). Consumer behavior: concepts and applications. McGraw-Hill Series in Marketing (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070387584.

- Rogers, Everett M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations (1st ed.). New York: Free Press of Glencoe. OCLC 254636.

- Rogers, Everett M. (1983). Diffusion of innovations (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press of Glencoe. ISBN 9780029266502.

- Wejnert, Barbara (August 2002). "Integrating models of diffusion of innovations: a conceptual framework". Annual Review of Sociology. 28: 297–326. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141051. JSTOR 3069244. S2CID 14699184.

Notes

- Rogers, Everett (16 August 2003). Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5823-4.

- Schirtzinger, Warren (1989-08-22). "Crossing the Chasm Summary". High Tech Strategies. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- Rogers 1962, p. 150.

- Kinnunen, J. (1996). "Gabriel Tarde as a Founding Father of Innovation Diffusion Research". Acta Sociologica. 39 (4): 431–442. doi:10.1177/000169939603900404. S2CID 145291431.

- Valente, T.; Rogers, E. (1995). "The Origins and Development of the Diffusion of Innovations Paradigm as an Example of Scientific Growth". Science Communication. 16 (3): 242–273. doi:10.1177/1075547095016003002. PMID 12319357. S2CID 24497472.

- Ryan, B.; Gross, N. (1943). "The diffusion of hybrid seed corn in two Iowa communities". Rural Sociology. 8 (1).

- Mascia, Michael B.; Mills, Morena (2018). "When conservation goes viral: The diffusion of innovative biodiversity conservation policies and practices". Conservation Letters. 11 (3): e12442. doi:10.1111/conl.12442. ISSN 1755-263X.

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O.; Peacock, R. (2005). "Storylines of Research in Diffusion of Innovation: A Meta-narrative Approach to Systematic Review". Social Science & Medicine. 61 (2): 417–430. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001. PMID 15893056.

- Berwick, DM. (2003). "Disseminate Innovations in Health Care". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 289 (15): 1969–1975. doi:10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. PMID 12697800. S2CID 26283930.

- Pemberton, H. Earl (1936). "The Curve of Culture Diffusion Rate". American Sociological Review. 1 (4): 547–556. doi:10.2307/2084831. JSTOR 2084831.

- "institutional diffusion | World Bank Blogs". Blogs.worldbank.org. 2009-11-16. Archived from the original on 2014-08-04. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- Rogers 1962, p. 83.

- Rogers, E.; Shoemaker, F. (1971). Communication of innovations: a cross-cultural approach. Free Press.

- Easley, D.; Kleinberg, J. (2010). Networks, Crowds and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 497–535. ISBN 9780521195331.

- Rogers 1983, p. 11.

- Meyer, G. (2004). "Diffusion Methodology: Time to Innovate?". Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives. 9 (S1): 59–69. doi:10.1080/10810730490271539. PMID 14960404. S2CID 20932024.

- Rogers 1983, p. 17.

- Ghoshal, DS.; Bartlett, C. (1988). "Creation, Adoption and Diffusion of Innovations by Subsidiaries of Multinational Corporations". The Journal of International Business Studies. 19 (3): 372. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490388. S2CID 167588113.

- Rogers 1983, p. 21, 23.

- Strang, D.; Soule, Sarah (1998). "Diffusion in Organizations and Social Movements: From Hybrid Corn to Poison Pills". Annual Review of Sociology. 24: 265–290. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.265.

- Rogers 1983, p. 24.

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. (2004). "Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations". The Milbank Quarterly. 82 (4): 581–629. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378x.2004.00325.x. PMC 2690184. PMID 15595944.

- Rogers 1962.

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. (2004). "Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations". The Milbank Quarterly. 82 (4): 597–598. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378x.2004.00325.x. PMC 2690184. PMID 15595944.

- Denis, JL; Herbert, Y; Langley, A; Lozeau, D; Trottier, LH (2002). "Explaining Diffusion Patterns for Complex Health Care Innovations". Health Care Management Review. 27 (3): 60–73. doi:10.1097/00004010-200207000-00007. PMID 12146784. S2CID 6388134.

- Meyer, AD; Goes, JB (1988). "Organizational Assimilation of Innovations: A multi-Level Contextual Analysis". Academy of Management Review. 31 (4): 897–923. doi:10.5465/256344. JSTOR 256344. S2CID 17430228.

- Dobbins, R; Cockerill, R; Barnsley, J (2001). "Factors Affecting the Utilization of Systematic Reviews". International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 17 (2): 203–14. doi:10.1017/s0266462300105069. PMID 11446132. S2CID 25109112.

- Aubert, BA; Hamel, G (2001). "Adoption of Smart Cards in the Medical Sector: The Canadian Experience". Social Science & Medicine. 53 (7): 879–94. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00388-9. PMID 11522135.

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. (2004). "Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations". The Milbank Quarterly. 82 (4): 599–600. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378x.2004.00325.x. PMC 2690184. PMID 15595944.

- Ferlie, E; Gabbay, L; Fitzgerald, L; Locock, L; Dopson, S (2001). "Organisational Behaviour and Organisational Studies in Health Care: Reflections on the Future". In Ashburner, L (ed.). Evidence-Based Medicine and Organisational Change: An Overview of Some Recent Qualitiative Research. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Eveland, JD (1986). "Diffusion, Technology Transfer and Implementation". Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization. 8 (2): 303–322. doi:10.1177/107554708600800214. S2CID 143645140.

- Rogers, EM (1995). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. (2004). "Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations". The Milbank Quarterly. 82 (4): 607–610. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378x.2004.00325.x. PMC 2690184. PMID 15595944.

- Gustafson, DH; F Sanfort, M; Eichler, M; ADams, L; Bisognano, M; Steudel, H (2003). "Developing and Testing a Model to Predict Outcomes of Organizational Change". Health Services Research. 38 (2): 751–776. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.00143. PMC 1360903. PMID 12785571.

- Øvretveit, J; Bate, P; Cleary, P; Cretin, S; Gustafson, D; McInnes, K; McLeod, H; Molfenter, T; Plsek, P; Robert, G; Shortell, S; Wilson, T (2002). "Quality Collaboratives: Lessons from Research". Quality and Safety in Health Care. 11 (4): 345–51. doi:10.1136/qhc.11.4.345. PMC 1757995. PMID 12468695.

- Exworthy, M; Berney, L; Powell, M (2003). "How Great Expectations in Westminster May Be Dashed Locally: The Local Implementation of National Policy on Health Inequalities". Policy & Politics. 30 (1): 79–96. doi:10.1332/0305573022501584.

- Li, Jerry (2020), "Blockchain technology adoption: Examining the Fundamental Drivers", Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Management Science and Industrial Engineering, ACM Publication, April 2020, pp. 253–260. doi:10.1145/3396743.3396750

- Rogers 1962, p. 79.

- Newell, S. (2001). "Management Fads and Fashions". Organization. 8 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1177/135050840181001.

- Rogers, EM (1995). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press. p. 372.

- Rogers 1962, p. 134.

- Fisher, J.C. (1971). "A simple substitution model of technological change". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 3: 75–88. doi:10.1016/S0040-1625(71)80005-7.

- Rogers 1962, p. 282.

- Rogers 1962, p. 283.

- Gibbons, D (2004). "Network Structure and Innovation Ambiguity Effects on Diffusion in Dynamic Organizational Fields" (PDF). The Academy of Management Journal (Submitted manuscript). 47 (6): 938–951. doi:10.2307/20159633. hdl:10945/46065. JSTOR 20159633.

- Choi, H; Kim, S-H; Lee, J (2010). "Role of Network Structure and Network Effects in Diffusion of Innovations". Industrial Marketing Management. 39 (1): 170–177. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.08.006. S2CID 61392977.

- Burt, R. S. (1973). "The differential impact of social integration on participation in the diffusion of innovations". Social Science Research. 2 (2): 125–144. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(73)90015-X.

- Rogers, E (1995). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

- Rogers 1983, p. 18.

- McPherson, M; Smith-Lovin, L; Cook, JM (2001). "Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks". Annual Review of Sociology. 27: 415–44. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415. S2CID 2341021.

- Rogers 1983, p. 19.

- Rostila, M (2010). "Birds of a feather flock together - and fall ill? Migrant Homophily and health in Sweden". Sociology of Health & Illness. 32 (3): 382–399. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01196.x. PMID 20415788.

- Rogers, E; Bhowmik, D (1970). "Homophily-Heterophily: Relational Concepts for Communication Research". Public Opinion Quarterly. 34 (4): 523–538. doi:10.1086/267838.

- Centola, D (2011). "An Experimental Study of Homophily in the Adoption of Health Behavior". Science. 334 (6060): 1269–1272. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1269C. doi:10.1126/science.1207055. PMID 22144624. S2CID 44322077.

- Katz, Elihu; Lazarsfeld, Paul (1970). Personal Influence, the Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-3070-6.

- Rogers 1962, p. 219.

- Radford, Scott K. (2011). "Linking Innovation to Design: Consumer Responses to Visual Product Newness". Journal of Product Innovation Management. 28 (s1): 208–220. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2011.00871.x.

- Carroll, N. (2014). Actor-Network Theory: A Bureaucratic View of Public Service Innovation, Chapter 7, Technological Advancements and the Impact of Actor-Network Theory, pp. 115-144, Publisher IGI Global, Hershey, PA

- Economic policy making in evolutionary perspective Archived 2011-09-20 at the Wayback Machine, by Ulrich Witt, Max-Planck-Institute for Research into Economic Systems.

- Andrews, David (1 January 1984). The IRG Solution: Hierarchical Incompetence and how to Overcome it. Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0-285-62662-1.

- Valente, T. W. (1996). "Social network thresholds in the diffusion of innovations". Social Networks. 18: 69–89. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(95)00256-1.

- Wear, Andrew (2008). "Innovation and community strength in Provincial Victoria" (PDF). Australasian Journal of Regional Studies. 14 (2): 195.

- Rogers 2003, p. 403.

- Stone, Diane (2012). "Transfer and Translation of Policy". Policy Studies. 33 (4): 483–499. doi:10.1080/01442872.2012.695933. S2CID 154487482.

- Marsh, D; Sharman, JC (2009). "Policy Diffusion and Policy Transfer". Policy Studies. 30 (3): 269–288. doi:10.1080/01442870902863851. S2CID 154771344.

- Berry, Frances Stokes (1990). "State Lottery Adoptions as Policy Innovations: An Event History Analysis". The American Political Science Review. 84 (2): 395–415. doi:10.2307/1963526. JSTOR 1963526. S2CID 143942476.

- Simmons, B. A.; Elkins, Z. (2004). "The Globalization of Liberalization: Policy Diffusion in the International Political Economy" (PDF). American Political Science Review (Submitted manuscript). 98: 171–189. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.459.2364. doi:10.1017/S0003055404001078. S2CID 13872025.

- Fabrizio Gilardi (July 2010). "Who Learns from What in Policy Diffusion Processes?". American Journal of Political Science. 54 (3): 650–666. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00452.x. S2CID 54851191.

- Jordana, J. (2011). "The Global Diffusion of Regulatory Agencies: Channels of Transfer and Stages of Diffusion". Comparative Political Studies. 44 (10): 1343–1369. doi:10.1177/0010414011407466. S2CID 157148193.

- Shipan, C; Volden, C (2008). "The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion". American Journal of Political Science (Submitted manuscript). 52 (4): 840–857. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.204.6531. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00346.x.

- Way, Christopher (2005). "Political Insecurity and the Diffusion of Financial Market Regulation". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 598: 125–144. doi:10.1177/0002716204272652. S2CID 154759501.

- Meseguer, Covadonga (2005). "Policy Learning, Policy Diffusion, and the Making of a New Order". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 598: 67–82. doi:10.1177/0002716204272372. S2CID 154401428.

- Peres, Renana (2010). "Innovation diffusion and new product growth models: A critical review and research directions". International Journal of Research in Marketing. 27 (2): 91–106. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2009.12.012.

- Eveland, J. D. (1986). "Diffusion, Technology Transfer, and Implementation: Thinking and Talking About Change". Science Communication. 8 (2): 303–322. doi:10.1177/107554708600800214. S2CID 143645140.

- Moore, Stephen; Simon, Julian (Dec 15, 1999). "The Greatest Century That Ever Was: 25 Miraculous Trends of the last 100 Years" (PDF). Policy Analysis. The Cato Institute (364).

- Grübler, Arnulf (1990). The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures: Dynamics of Evolution and Technological Change in Transport (PDF). Heidelberg and New York: Physica-Verlag. ISBN 3-7908-0479-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2011.

- Rogers 2003, p. 470.

- Wejnert 2002, p. 299.

- Wejnert 2002, p. 301.

- Bass, Frank M. (1969). "A New Product Growth for Model Consumer Durables". Management Science. 15 (5): 215–227. doi:10.1287/mnsc.15.5.215. ISSN 0025-1909.

- Hochbaum, Dorit S. (2011). "Rating Customers According to Their Promptness to Adopt New Products". Operations Research. 59 (5): 1171–1183. doi:10.1287/opre.1110.0963. S2CID 17397292.

- Nasrinpour, Hamid Reza; Friesen, Marcia R.; McLeod, Robert D. (2016-11-22). "An Agent-Based Model of Message Propagation in the Facebook Electronic Social Network". arXiv:1611.07454 [cs.SI].

- What Math Can Tell Us About Technology's Spread Through Cities.

- How does innovation take hold in a community? Math modeling can provide clues

- Watts, D. J. (2002). "A simple model of global cascades on random networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (9): 5766–5771. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.5766W. doi:10.1073/pnas.082090499. PMC 122850. PMID 16578874.

- Easley, D; Kleinberg, J (2010). Networks, Crowds and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 497–531. ISBN 9780521195331.

- McCullen, N. J. (2013). "Multiparameter Models of Innovation Diffusion on Complex Networks". SIAM Journal on Applied Dynamical Systems. 12 (1): 515–532. arXiv:1207.4933. doi:10.1137/120885371.

- Meyers, P; Sivakumar, K; Nakata, C (1999). "Implementation of Industrial Process Innovations: Factors, Effects, and Marketing Implications". The Journal of Product Innovation Management. 16 (3): 295–311. doi:10.1111/1540-5885.1630295.

- Katz, E; Levin, M; Hamilton, H (1963). "Traditions of Research on the Diffusion of Innovation". American Sociological Review. 28 (2): 237–252. doi:10.2307/2090611. JSTOR 2090611.

- Damanpour, F (1996). "Organizational Complexity and Innovation: Developing and Testing Multiple Contingency Models". Management Science. 42 (5): 693–716. doi:10.1287/mnsc.42.5.693.

- Plsek, P; Greenhalgh, T (2001). "The challenge of complexity in health care". BMJ. 323 (7313): 625–628. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625. PMC 1121189. PMID 11557716.

- Downs, GW; Mohr, LB (1976). "Conceptual Issues in the Study of Innovation". Administrative Science Quarterly. 21 (4): 700–714. doi:10.2307/2391725. JSTOR 2391725.

- Giesler, Markus (2012). "How Doppelgänger Brand Images Influence the Market Creation Process: Longitudinal Insights from the Rise of Botox Cosmetic". Journal of Marketing. 76 (6): 55–68. doi:10.1509/jm.10.0406. S2CID 167319134.

- Robertson, M; Swan, Jacky; Newell, Sue (1996). "The Role of Networks in the Diffusion of Technological Innovation". Journal of Management Studies. 33 (3): 333–359. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.1996.tb00805.x.

External links

- The Diffusion Simulation Game, about adopting an innovation in education.

- The Pencil Metaphor on diffusion of innovation.

- Diffusion of Innovations, Strategy and Innovations. The D.S.I Framework by Francisco Rodrigues Gomes, Academia.edu share research.