Disfranchisement after the Reconstruction era

Disfranchisement after the Reconstruction era[2] in the United States, especially in the Southern United States, was based on a series of laws, new constitutions, and practices in the South that were deliberately used to prevent black citizens from registering to vote and voting. These measures were enacted by the former Confederate states at the turn of the 20th century. Efforts were also made in Maryland, Kentucky, and Oklahoma.[3] Their actions were designed to thwart the objective of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1870, which prohibited states from depriving voters of their voting rights on the basis of race.[4] The laws were frequently written in ways to be ostensibly non-racial on paper (and thus not violate the Fifteenth Amendment), but were implemented in ways that selectively suppressed black voters apart from other voters.[5]

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

Beginning in the 1870s, white racists had used violence by domestic terrorism groups (such as the Ku Klux Klan), as well as fraud, to suppress black voters. After regaining control of the state legislatures, Southern Democrats were alarmed by a late 19th-century alliance between Republicans and Populists that cost them some elections. After achieving control of state legislatures, white conservatives added to previous efforts and achieved widespread disfranchisement by law: from 1890 to 1908, Southern state legislatures passed new constitutions, constitutional amendments, and laws that made voter registration and voting more difficult, especially when administered by white staff in a discriminatory way. They succeeded in disenfranchising most of the black citizens, as well as many poor whites in the South, and voter rolls dropped dramatically in each state. The Republican Party was nearly eliminated in the region for decades, and the Southern Democrats established one-party control throughout the Southern United States.[6]

In 1912, the Republican Party was split when Theodore Roosevelt ran against William Howard Taft, the party nominee. In the South by this time, the Republican Party had been hollowed out by the disfranchisement of African Americans, who were mostly excluded from voting. Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected as the first southern President since 1848. He was re-elected in 1916, in a much closer presidential contest. During his first term, Wilson satisfied the request of Southerners in his cabinet and instituted overt racial segregation throughout federal government workplaces, as well as racial discrimination in hiring. During World War I, American military forces were segregated, with black soldiers poorly trained and equipped.

Disfranchisement had far-reaching effects in the United States Congress, where the Democratic Solid South enjoyed "about 25 extra seats in Congress for each decade between 1903 and 1953".[nb 1][7] Also, the Democratic dominance in the South meant that southern senators and representatives became entrenched in Congress. They favored seniority privileges in Congress, which became the standard by 1920, and Southerners controlled chairmanships of important committees, as well as the leadership of the national Democratic Party.[7] During the Great Depression, legislation establishing numerous national social programs were passed without the representation of African Americans, leading to gaps in program coverage and discrimination against them in operations. In addition, because black Southerners were not listed on local voter rolls, they were automatically excluded from serving in local courts. Juries were all white across the South.

Political disfranchisement did not end until after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which authorized the federal government to monitor voter registration practices and elections where populations were historically underrepresented and to enforce constitutional voting rights. The challenge to voting rights has continued into the 21st century, as shown by numerous court cases in 2016 alone, though attempts to restrict voting rights for political advantage have not been confined to the Southern United States. Another method of seeking political advantage through the voting system is the gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, as was the case of North Carolina, which in January 2018 was declared by a federal court to be unconstitutional.[8] Such cases are expected to reach the Supreme Court of the United States.[9]

Background

The American Civil War ended in 1865, marking the start of the Reconstruction era in the eleven former[10] Confederate states. Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts, starting in 1867, establishing military districts to oversee the affairs of these states pending reconstruction.

During the Reconstruction era, blacks constituted absolute majorities of the populations in Mississippi and South Carolina, were equal to the white population in Louisiana, and represented more than 40 percent of the population in four other former Confederate states. In addition, the Reconstruction Acts and state Reconstruction constitutions and law barred many ex-Confederate Southern whites from holding office and, in some states, disenfranchised them unless they took a loyalty oath. Southern whites, fearing black domination, resisted the freedmen's exercise of political power.[11] In 1867, black men voted for the first time. By the 1868 presidential election, Texas, Mississippi, and Virginia had still not been re-admitted to the Union. General Ulysses S. Grant was elected as president thanks in part to 700,000 black voters. In February 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified; it was designed to protect blacks' right to vote from infringement by the states. At the same time, by 1870 all Southern states had dropped enforcement of disfranchisement of ex-Confederates with the exception of Arkansas, where disfranchisement of ex-Confederates was dropped in the aftermath of the Brooks-Baxter War in 1874.

White supremacist paramilitary organizations, allied with Southern Democrats, used intimidation, violence and even committed assassinations in order to repress blacks and prevent them from exercising their civil and political rights in elections from 1868 until the mid-1870s. The insurgent Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was formed in 1865 in Tennessee (as a backlash to defeat in the war) and it quickly became a powerful secret vigilante group, with chapters across the South. The Klan initiated a campaign of intimidation directed against blacks and sympathetic whites. Their violence included vandalism and destruction of property, physical attacks and assassinations, and lynchings. Teachers who came from the North to teach freedmen were sometimes attacked or intimidated as well. In 1870, the attempt of North Carolina's Republican Governor William W. Holden to suppress the Klan, known as the Kirk-Holden War, led to a backlash by whites, the election of a Democratic General Assembly in August 1870, and his impeachment and removal from office.

The toll of Klan murders and attacks led Congress to pass laws to end the violence. In 1870, the strongly Republican Congress passed the Enforcement Acts, imposing penalties for conspiracy to deny black suffrage.[12] The Acts empowered the President to deploy the armed forces to suppress organizations that deprived people of rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Organizations whose members appeared in arms were considered in rebellion against the United States. The President could suspend habeas corpus under those circumstances. President Grant used these provisions in parts of the Carolinas in late 1871. United States marshals supervised state voter registrations and elections and could summon the help of military or naval forces if needed.[12] These measures led to the demise of the first Klan by the early 1870s.

New paramilitary groups quickly sprang up, as tens of thousands of veterans belonged to gun clubs and similar groups. A second wave of violence began, resulting in over 1,000 deaths, usually black or Republican. The Supreme Court ruled in 1876 in United States v. Cruikshank, arising from trials related to the Colfax Massacre, that protections of the Fourteenth Amendment, which the Enforcement Acts were intended to support, did not apply to the actions of individuals, but only to the actions of state governments. They recommended that persons seek relief from state courts, which had not been supportive of freedmen's rights.

The paramilitary organizations that arose in the mid to late 1870s were part of continuing insurgency in the South after the Civil War, as armed veterans in the South resisted social changes, and worked to prevent black Americans and other Republicans from voting and running for office. Such groups included the White League, formed in Louisiana in 1874 from white militias, with chapters forming in other Southern states; the Red Shirts, formed in 1875 in Mississippi but also active in North Carolina and South Carolina; and other "White Liners," such as rifle clubs and the Knights of the White Camellia. Compared to the Klan, they were open societies, better organized and devoted to the political goal of regaining control of the state legislatures and suppressing Republicans, including most blacks. They often solicited newspaper coverage for publicity to increase their threat. The scale of operations was such that in 1876, North Carolina had 20,000 men in rifle clubs. Made up of well-armed Confederate veterans, a class that covered most adult men who could have fought in the war, the paramilitary groups worked for political aims: to turn Republicans out of office, disrupt their organizing, and use force to intimidate and terrorize freedmen to keep them away from the polls. Such groups have been described as "the military arm of the Democratic Party".[13]

They were instrumental in many Southern states in driving blacks away from the polls and ensuring a white Democratic takeover of legislatures and governorships in most Southern states in the 1870s, most notoriously during the controversial 1876 elections. As a result of a national Compromise of 1877 arising from the 1876 presidential election, the federal government withdrew its military forces from the South, formally ending the Reconstruction era. By that time, Southern Democrats had effectively regained control in Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida – they identified as the Redeemers. In the South, the process of white Democrats regaining control of state governments has been called "the Redemption". African-American historians sometimes call the Compromise of 1877 "The Great Betrayal".[14]

Post-Reconstruction disfranchisement

Following continuing violence around elections as insurgents worked to suppress black voting, the Democratic-dominated Southern states passed legislation to create barriers to voter registrations by blacks and poor whites, starting with the Georgia poll tax in 1877. Other measures followed, particularly near the end of the century, after a Republican-Populist alliance caused the Democrats to temporarily lose some Congressional seats and control of some gubernatorial positions.

To secure their power, the Democrats worked to exclude blacks (and most Republicans) from politics. The results could be seen across the South. After Reconstruction, Tennessee initially had the most "consistently competitive political system in the South".[15] A bitter election battle in 1888, marked by unmatched corruption and violence, resulted in white Democrats taking over the state legislature. To consolidate their power, they worked to suppress the black vote and sharply reduced it through changes in voter registration, requiring poll taxes, as well as changing election procedures to make voting more complex.

In 1890, Mississippi adopted a new constitution, which contained provisions for voter registration that required voters to pay poll taxes and pass a literacy test. The literacy test was subjectively applied by white administrators, and the two provisions effectively disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. The constitutional provisions survived a Supreme Court challenge in Williams v. Mississippi (1898). Other southern states quickly adopted new constitutions and what they called the "Mississippi plan". By 1908, all states of the former Confederacy had passed new constitutions or suffrage amendments, sometimes bypassing general elections to achieve this. Legislators created a variety of barriers, including longer residency requirements, rule variations, literacy and understanding tests, which were subjectively applied against minorities, or were particularly hard for the poor to fulfill.[16] Such constitutional provisions were unsuccessfully challenged at the Supreme Court in Giles v. Harris (1903). In practice, these provisions, including white primaries, created a maze that blocked most blacks and many poor whites from voting in Southern states until after the passage of federal civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s.[17] Voter registration and turnout dropped sharply across the South, as most blacks and many poor whites were excluded from the political system.

Senator and former South Carolina Governor Benjamin Tillman defended this on the floor of the Senate:

In my State there were 135,000 negro voters, or negroes of voting age, and some 90,000 or 95,000 white voters.... Now, I want to ask you, with a free vote and a fair count, how are you going to beat 135,000 by 95,000? How are you going to do it? You had set us an impossible task.

We did not disfranchise the negroes until 1895. Then we had a constitutional convention convened which took the matter up calmly, deliberately, and avowedly with the purpose of disfranchising as many of them as we could under the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. We adopted the educational qualification as the only means left to us, and the negro is as contented and as prosperous and as well protected in South Carolina to-day as in any State of the Union south of the Potomac. He is not meddling with politics, for he found that the more he meddled with them the worse off he got. As to his “rights”—I will not discuss them now. We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will.... I would to God the last one of them was in Africa and that none of them had ever been brought to our shores.[18]

The disfranchisement of a large proportion of voters attracted the attention of Congress, and as early as 1900 some members proposed stripping the South of seats, related to the number of people who were barred from voting. Apportionment of seats was still based on total population (with the assumption of the usual number of voting males in relation to the residents); as a result, white Southerners commanded a number of seats far out of proportion to the voters they represented.[19] In the end, Congress did not act on this issue, as the Southern bloc of Democrats had sufficient power to reject or stall such action. For decades, white Southern Democrats exercised Congressional representation derived from a full count of the population, but they disfranchised several million black and white citizens. Southern white Democrats comprised the "Solid South", a powerful voting bloc in Congress until the mid-20th century. Their representatives, re-elected repeatedly by one-party states, exercised the power of seniority, controlling numerous chairmanships of important committees in both houses. Their power allowed them to have control over rules, budgets and important patronage projects, among other issues, as well as to defeat bills to make lynching a federal crime.[17]

New state constitutions, 1890 to 1908

Despite white Southerners' complaints about Reconstruction, several Southern states kept most provisions of their Reconstruction constitutions for more than two decades, until late in the 19th century.[20] In some states, the number of blacks elected to local offices reached a peak in the 1880s although Reconstruction had ended. They had an influence at the local level, where much of government took place, although they did not win many statewide or national seats. Subsequently, state legislatures passed restrictive laws or constitutions that made voter registration and election rules more complicated. As literacy tests and other restrictions could be applied subjectively, these changes sharply limited the vote by most blacks and, often, many poor whites; voter rolls dropped across the South into the new century.

Florida approved a new constitution in 1885 that included provisions for poll taxes as a prerequisite for voter registration and voting. From 1890 to 1908, ten of the eleven Southern states rewrote their constitutions. All included provisions that effectively restricted voter registration and suffrage, including requirements for poll taxes, increased residency, and subjective literacy tests.[21]

With educational improvements, blacks had markedly increased their rate of literacy. By 1891, their illiteracy had declined to 58 percent, while the rate of white illiteracy in the South at that time was 31 percent.[22] Some states used grandfather clauses to exempt white voters from literacy tests altogether. Other states required otherwise eligible black voters to meet literacy and knowledge requirements to the satisfaction of white registrars, who applied subjective judgment and, in the process, rejected most black voters. By 1900, the majority of blacks were literate, but even many of the best-educated of these men continued to "fail" the literacy tests administered by white registrars.

The historian J. Morgan Kousser noted, "Within the Democratic party, the chief impetus for restriction came from the black belt members," whom he identified as "always socioeconomically privileged." In addition to wanting to affirm white supremacy, the planter and business elite were concerned about voting by lower-class and uneducated whites. Kousser found, "They disfranchised these whites as willingly as they deprived blacks of the vote."[23] Perman noted the goals of disfranchisement resulted from several factors. Competition between white elites and white lower classes, for example, and a desire to prevent alliances between lower-class white and black Americans, as had been seen in Populist-Republican alliances, led white Democratic legislators to restrict voter rolls.[21]

With the passage of new constitutions, Southern states adopted provisions that caused disfranchisement of large portions of their populations by skirting US constitutional protections of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. While their voter registration requirements applied to all citizens, in practice they disenfranchised most blacks. As in Alabama, they also "would remove [from voter registration rolls] the less educated, less organized, more impoverished whites as well – and that would ensure one-party Democratic rules through most of the 20th century in the South".[17][24]

The new provisions of the state constitutions almost entirely eliminated black voting. Although nothing approaching precise data exists, it is estimated that in the late 1930s less than one percent of blacks in the Deep South and around five percent in the Rim South were registered to vote,[25] and that the proportion actually voting even in general elections, which were of no consequence due to complete Democratic dominance, was much smaller still. Secondly, the Democratic legislatures passed Jim Crow laws to assert white supremacy, establish racial segregation in public facilities, and treat blacks as second-class citizens. The landmark court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) held that "separate but equal" facilities, as on railroad cars, were constitutional. The new constitutions passed numerous Supreme Court challenges. In cases where a particular restriction was overruled by the Supreme Court in the early 20th century, states quickly devised new methods of excluding most blacks from voting, such as the white primary. Democratic Party primaries became the only competitive contests in southern states.

For the national Democratic Party, the alignment after Reconstruction resulted in a powerful Southern region that was useful for congressional clout. Nevertheless, prior to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the "Solid South" inhibited the national party from fulfilling center-left initiatives desired since the days of William Jennings Bryan. Woodrow Wilson, one of two Democrats elected to the presidency between Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt, was the first Southerner elected after 1856.[nb 2] He benefited by the disfranchisement of blacks and crippling of the Republican Party in the South.[7] Soon after taking office, Wilson directed the segregation of federal facilities in the District of Columbia, which had been integrated during Reconstruction.

Case studies

Southern black populations in 1900

| Population of African Americans in Southern states, 1900 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of African Americans[26] | % of Population[26] | Year of law or constitution[27] | |

| Alabama | 827,545 | 45.26 | 1901 |

| Arkansas | 366,984 | 27.98 | 1891 |

| Florida | 231,209 | 43.74 | 1885–1889 |

| Georgia | 1,045,037 | 46.70 | 1908 |

| Louisiana | 652,013 | 47.19 | 1898 |

| Mississippi | 910,060 | 58.66 | 1890 |

| North Carolina | 630,207 | 33.28 | 1900 |

| South Carolina | 782,509 | 58.38 | 1895 |

| Tennessee | 480,430 | 23.77 | 1889 laws |

| Texas | 622,041 | 20.40 | 1901 / 1923 laws |

| Virginia | 661,329 | 35.69 | 1902 |

| Total | 7,199,364 | 37.94 | — |

Louisiana

With a population evenly divided between races, in 1896 there were 130,334 black voters on the Louisiana registration rolls and about the same number of whites.[28] Louisiana State legislators passed a new constitution in 1898 that included requirements for applicants to pass a literacy test in English or his native language in order to register to vote or to certify owning $300 worth of property, known as a property requirement. The literacy test was administered by the voting registrar; in practice, they were white Democrats. Provisions in the constitution also included a grandfather clause, which provided a loophole to enable illiterate whites to register to vote. It said that "Any citizen who was a voter on January 1, 1867, or his son or grandson, or any person naturalized prior to January 1, 1898, if applying for registration before September 1, 1898, might vote, notwithstanding illiteracy or poverty." Separate registration lists were kept for whites and blacks, making it easy for white registrars to discriminate against blacks in literacy tests. The constitution of 1898 also required a person to satisfy a longer residency requirement in the state, county, parish, and precinct before voting than did the constitution of 1879. This worked against the lower classes, who were more likely to move frequently for work, especially in agricultural areas where there were many migrant workers and sharecroppers.

The effect of these changes on the population of black voters in Louisiana was devastating; by 1900 black voters were reduced from 130,334 to 5,320 on the rolls. By 1910, only 730 blacks were registered, less than 0.5% of eligible black men. "In 27 of the state's sixty parishes, not a single black voter was registered any longer; in nine more parishes, only one black voter was."[28]

North Carolina

In 1894, a coalition of Republicans and the Populist Party won control of the North Carolina state legislature (and with it, the ability to elect two US Senators) and were successful in electing several US Representatives elected through electoral fusion.[29] The fusion coalition made impressive gains in the 1896 election when their legislative majority expanded. Republican Daniel Lindsay Russell won the gubernatorial race in 1897, the first Republican governor of the state since the end of Reconstruction in 1877. The election also resulted in more than 1,000 elected or appointed black officials, including the election in 1897 of George Henry White to Congress, as a member of the House of Representatives.

At the 1898 election, the Democrats ran on White Supremacy and disfranchisement in a bitter race-baiting campaign led by Furnifold McLendel Simmons and Josephus Daniels, editor and publisher of The Raleigh News & Observer. The Republican/Populist coalition disintegrated, and the Democrats won the North Carolina 1898 election and the following 1900 election. Simmons was elected as the state's US senator in 1900, holding office until 1931 through multiple re-elections by the state legislature and by popular vote after 1920.

The Democrats used their power in the state legislature to disenfranchise minorities, primarily blacks, and ensure that Democratic Party and white power would not be threatened again.[15][29][30] They passed laws restricting voter registration. In 1900 the Democrats adopted a constitutional suffrage amendment which lengthened the residence period required before registration and enacted both an educational qualification (to be assessed by a registrar, which meant that it could be subjectively applied) and prepayment of a poll tax. A grandfather clause exempted from the poll tax those entitled to vote on January 1, 1867.[31] The legislature also passed Jim Crow laws establishing racial segregation in public facilities and transportation.

The effect in North Carolina was the complete elimination of black voters from voter rolls by 1904. Contemporary accounts estimated that seventy-five thousand black male citizens lost the vote.[32][33] In 1900 blacks numbered 630,207 citizens, about 33% of the state's total population.[34] The growth of the thriving black middle class was slowed. In North Carolina and other Southern states, there were also the insidious effects of invisibility: "[w]ithin a decade of disfranchisement, the white supremacy campaign had erased the image of the black middle class from the minds of white North Carolinians."[35]

Virginia

In Virginia, Democrats sought disfranchisement in the late 19th century after a coalition of white and black Republicans with populist Democrats had come to power; the coalition had been formalized as the Readjuster Party. The Readjuster Party held control from 1881 to 1883, electing a governor and controlling the legislature, which also elected a US Senator from the state. As in North Carolina, state Democrats were able to divide Readjuster supporters through appeals to White Supremacy. After regaining power, Democrats changed state laws and the constitution in 1902 to disenfranchise blacks. They ratified the new constitution in the legislature and did not submit it to popular vote. Voting in Virginia fell by nearly half as a result of the disfranchisement of blacks.[36][37] The eighty-year stretch of white Democratic control ended only in the late 1960s after passage and enforcement of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the collapse of the Byrd Organization machine.

Border states: failed disfranchisement

The five border states of Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky and Missouri, had legacies similar to the Confederate slave states from the Civil War. The border states, all slave states, also established laws requiring racial segregation between the 1880s and 1900s; however, disfranchisement of blacks was never attained to any significant degree. Most Border States did attempt such disfranchisement during the 1900s.

The causes of failure to disenfranchise blacks and poor whites in the Border States, as compared to their success for well over half a century in former Confederate states, were complicated. During the 1900s Maryland was vigorously divided between supporters and opponents of disfranchisement, but it had a large and increasingly educated black community concentrated in Baltimore. This city had many free blacks before the Civil War and they had established both economic and political power.[38] The state legislature passed a poll tax in 1904, but incurred vigorous opposition and repealed it in 1911. Despite support among conservative whites in the conservative Eastern Shore, referendums for bills to disenfranchise blacks failed three times in 1905, 1908, and 1910, with the last vote being the most decisive.[38] The existence of substantial Italian immigration completely absent from the Confederacy meant that these immigrants were exposed to the possibility of disfranchisement, but much more critically allowed for much stronger resistance amongst the white population.[39]

In Kentucky, Lexington's city government had passed a poll tax in 1901, but it was declared invalid in state circuit courts.[40] Six years later, a new state legislative effort to disenfranchise blacks failed because of the strong organization of the Republican Party in pro-Union regions of the state.[40]

Methods of disfranchisement

Poll taxes

Proof of payment of a poll tax was a prerequisite to voter registration in Florida, Alabama, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia (1877), North and South Carolina, Virginia (until 1882 and again from 1902 with its new constitution),[36][37] Texas (1902)[41] and in some northern and western states. The Texas poll tax "required otherwise eligible voters to pay between $1.50 and $1.75 to register to vote – a lot of money at the time, and a big barrier to the working classes and poor".[41] Georgia created a cumulative poll tax requirement in 1877: men of any race 21 to 60 years of age had to pay a sum of money for every year from the time they had turned 21, or from the time that the law took effect.[42]

The poll tax requirements applied to whites as well as blacks, and also adversely affected poor citizens. Many states required payment of the tax at a time separate from the election, and then required voters to bring receipts with them to the polls. If they could not locate such receipts, they could not vote. In addition, many states surrounded registration and voting with other complex record-keeping requirements.[12] These were particularly difficult for sharecropper and tenant farmers to comply with, as they moved frequently.

The poll tax was sometimes used alone or together with a literacy qualification. In a kind of grandfather clause, North Carolina in 1900 exempted from the poll tax those men entitled to vote as of January 1, 1867. This excluded all blacks in the State, who did not have suffrage before that date.[31]

Educational and character requirements

Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee, created an educational requirement, with review by a local registrar of a voter's qualifications. In 1898 Georgia rejected such a device.

Alabama delegates at first hesitated, out of concern that illiterate whites would lose their votes. After the legislature stated that the new constitution would not disenfranchise any white voters and that it would be submitted to the people for ratification, Alabama passed an educational requirement. It was ratified at the polls in November 1901. Its distinctive feature was the "good character clause" (also known as the "grandfather clause"). An appointment board in each county could register "all voters under the present [previous] law" who were veterans or the lawful descendants of such, and "all who are of good character and understand the duties and obligations of citizenship". This gave the board discretion to approve voters on a case-by-case basis. In practice, they enfranchised many whites but rejected both poor whites and blacks. Most of the latter had been slaves and unable to attain military service.[12]

South Carolina, Louisiana (1889), and later, Virginia incorporated an educational requirement in their new constitutions. In 1902 Virginia adopted a constitution with the "understanding" clause as a literacy test to use until 1904. In addition, the application for registration had to be in the applicant's handwriting and written in the presence of the registrar. Thus, someone who could not write, could not vote.[12]

Eight Box Law

By 1882, the Democrats were firmly in power in South Carolina. Republican voters were mostly limited to the majority-black counties of Beaufort and Georgetown. Because the state had a large black-majority population (nearly sixty percent in 1890),[43] white Democrats had narrow margins in many counties and feared a possible resurgence of black Republican voters at the polls. To remove the black threat, the General Assembly created an indirect literacy test, called the "Eight Box Law".

The law required a separate box for ballots for each office; a voter had to insert the ballot into the corresponding box or it would not count. The ballots could not have party symbols on them. They had to be of the correct size and type of paper. Many ballots were arbitrarily rejected because they slightly deviated from the requirements. Ballots could also randomly be rejected if there were more ballots in a box than registered voters.[44]

The multiple-ballot box law was challenged in court. On May 8, 1895, Judge Nathan Goff of the United States Circuit Court declared the provision unconstitutional and enjoined the state from taking further action under it. But in June 1895, the US Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed Goff and dissolved the injunction,[45] leaving the way open for a convention.

The constitutional convention met on September 10 and adjourned on December 4, 1895. By the new constitution, South Carolina adopted the Mississippi Plan until January 1, 1898. Any male citizen could be registered who was able to read a section of the constitution or to satisfy the election officer that he understood it when read to him. Those thus registered were to remain voters for life. Under the new constitution and application of literacy practices, black voters were dropped in great number from the registration rolls: by 1896, in a state where according to the 1890 census blacks numbered 728,934 and comprised nearly sixty percent of the total population,[43] only 5,500 black voters had succeeded in registering.[28]

Grandfather clause

States also used grandfather clauses to enable illiterate whites who could not pass a literacy test to vote. It allowed a man to vote if his grandfather or father had voted prior to January 1, 1867; at that time, most African Americans had been slaves, while free people of color, even if property owners, and freedmen were ineligible to vote until 1870.[nb 3]

Justice Benjamin Curtis' dissent in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) had noted that free people of color in numerous states had the right to vote at the time of the Articles of Confederation (as part of the argument about whether people of African descent could be citizens of the new United States):

Of this, there can be no doubt. At the time of the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, all free native-born inhabitants of the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina, though descended from African slaves, were not only citizens of those States, but much of them as had the other necessary qualifications possessed the franchise of electors, on equal terms with other citizens.[46]

North Carolina's constitutional amendment of 1900 exempted from the poll tax those men entitled to vote as of January 1, 1867, another type of use of a grandfather clause.[31] Virginia also used a type of grandfather clause.[36][37]

In Guinn v. United States (1915), the Supreme Court invalidated the Oklahoma Constitution's "old soldier" and "grandfather clause" exemptions from literacy tests. In practice, these had disenfranchised blacks, as had occurred in numerous Southern states. This decision affected similar provisions in the constitutions of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia election rules. Oklahoma and other states quickly reacted by passing laws that created other rules for voter registration that worked against blacks and minorities.[47] Guinn was the first of many cases in which the NAACP filed a brief challenging discriminatory electoral rules.

In Lane v. Wilson (1939), the Supreme Court invalidated an Oklahoma provision designed to disenfranchise blacks. It had replaced the clause struck down in Guinn. This clause permanently disenfranchised everyone qualified to vote who had not registered to vote in a twelve-day window between April 30 and May 11, 1916, except for those who had voted in 1914. While designed to be more resistant to challenges based on discrimination, as the law did not specifically mention race, the Court struck it down partially because it relied on the 1914 election, when voters had been discriminated against under the rule invalidated in Guinn.[48]

White primaries

About the turn of the 20th century, white members of the Democratic Party in some Southern states devised rules that excluded blacks and other minorities from participating in party primaries. These became common for all elections. As the Democratic Party was dominant and the only competitive voting was in the primaries, barring minority voters from the primaries was another means of excluding them from politics. Court challenges overturned the white primary system, but many states then passed laws that authorized political parties to set up the rules for their own systems, such as the white primary. Texas, for instance, passed such state law in 1923. It was used to bar Mexican Americans as well as black Americans from voting; it survived challenges to the US Supreme Court until the 1940s.[49]

Congressional response

The North had heard the South's version of Reconstruction abuses, such as financial corruption, high taxes, and incompetent freedmen. Industry wanted to invest in the South and not worry about political problems. In addition, reconciliation between white veterans of the North and South reached a peak in the early 20th century. As historian David Blight demonstrated in Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, reconciliation meant the pushing aside by whites of the major issues of race and suffrage. Southern whites were effective for many years at having their version of history accepted, especially as it was confirmed in ensuing decades by influential historians of the Dunning School at Columbia University and other institutions.

Disfranchisement of black Americans in the South was covered by national newspapers and magazines as new laws and constitutions were created, and many Northerners were outraged and alarmed. The Lodge Bill or Federal Elections Bill or Lodge Force Bill of 1890 was a bill drafted by Representative Henry Cabot Lodge (R) of Massachusetts and sponsored in the Senate by George Frisbie Hoar. It would have authorized federal electors to supervise elections under certain conditions. Due to a Senate filibuster, as well as a trade-off of support with Democrats by western Silver Republicans, the bill failed to pass.[50][51]

In 1900 the Committee of Census of Congress considered proposals for adding more seats to the House of Representatives because of the increased population. Proposals ranged for a total number of seats from 357 to 386. Edgar D. Crumpacker (R-IN) filed an independent report urging that the Southern states be stripped of seats due to the large numbers of voters they had disfranchised. He noted this was provided for in Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided for stripping representation from states that reduced suffrage due to race.[7] The Committee and House failed to agree on this proposal.[19] Supporters of black suffrage worked to secure Congressional investigation of disfranchisement, but concerted opposition of the Southern Democratic bloc was aroused, and the efforts failed.[12]

From 1896 to 1900, the House of Representatives with a Republican majority had acted in more than thirty cases to set aside election results from Southern states where the House Elections Committee had concluded that "black voters had been excluded due to fraud, violence, or intimidation." Nevertheless, in the early 20th century, it began to back off from its enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment and suggested that state and federal courts should exercise oversight of this issue. The Southern bloc of Democrats exercised increasing power in the House.[52] They had no interest in protecting suffrage for blacks.

In 1904 Congress administered a coup de grâce to efforts to investigate disfranchisement in its decision in the 1904 South Carolina election challenge of Dantzler v. Lever. The House Committee on Elections upheld Lever's victory. It suggested that citizens of South Carolina who believed their rights were denied should take their cases to the state courts, and ultimately, the US Supreme Court.[53] Blacks had no recourse through the Southern state courts, which would not uphold their rights. Because they were disfranchised, blacks could not serve on juries, and whites were clearly aligned against them on this and other racial issues.

Despite the Lever decision and domination of Congress by Democrats, some Northern Congressmen continued to raise the issue of black disfranchisement and resulting malapportionment. For instance, on December 6, 1920, Representative George H. Tinkham (R-MA) offered a resolution for the Committee of Census to investigate the alleged disfranchisement of blacks. His intention was to enforce the provisions of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments.[54]

In addition, he believed there should be reapportionment in the House related to the voting population of southern states, rather than the general population as enumerated in the census.[54] Such reapportionment was authorized by the Constitution and would reflect reality so that the South should not get credit for people and voters it had disfranchised. Tinkham detailed how outsized the South's representation was related to the total number of voters in each state, compared to other states with the same number of representatives:[54][nb 4]

- States with four representatives:

- Florida, with a total vote of 31,613.

- Colorado, with a total vote of 208,855.

- Maine, with a total vote of 121,836.

- States with six representatives:

- Nebraska, with a total vote of 216,014.

- West Virginia, with a total vote of 211,643.

- South Carolina, given seven representatives because of its total population (which was majority black), counted only 25,433 voters.

- States with eight representatives:

- Louisiana, with a total vote of 44,794.

- Kansas, with a total vote of 425,641.

- States with ten representatives:

- Alabama, with a total vote of 62,345.

- Minnesota, with a total vote of 299,127.

- Iowa, with a total vote of 316,377.

- California, with eleven representatives, had a total vote of 644,790.

- States with twelve representatives:

- Georgia, with a total vote of 59,196.

- New Jersey, with a total vote of 338,461.

- Indiana, with thirteen representatives, had a total vote of 565,216.

Tinkham was defeated by the Democratic Southern Bloc, and also by fears amongst the northern business elites of increasing the voting power of Northern urban working classes,[55] whom both northern business and Southern planter elites believed would vote for large-scale income redistribution at a Federal level.[56]

After Herbert Hoover was elected in a landslide in 1928, gaining support from five southern states, Tinkham renewed his effort in the spring of 1929 to persuade Congress to penalize southern states under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments for their racial discrimination. He suggested the reduction of their congressional delegations in proportion to the populations they had disenfranchised. He was defeated again by the Solid South. Its representatives had rallied in outrage that the First Lady had invited Jessie De Priest for tea to the White House with other congressional wives. She was the wife of Oscar Stanton De Priest from Chicago, the first African-American elected to Congress in the 20th century.[57]

Segregation of the federal service began under President Woodrow Wilson, ignoring complaints by the NAACP, which had supported his election in 1912.[58] The NAACP lobbied for the commissioning of African Americans as officers in World War I. It was arranged for W.E.B. Du Bois to receive an Army commission, but he failed his physical. In 1915 the NAACP organized public education and protests in cities across the nation against D.W. Griffith's film The Birth of a Nation, a film that glamorized the Ku Klux Klan and shown in the Wilson White House as a personal favor to its author, a college roommate of President Wilson. Boston and a few other cities refused to allow the film to open.

Legislative and cultural effects

20th-century Supreme Court decisions

Black Americans and their allies worked hard to regain their ability to exercise the constitutional rights of citizens. Booker T. Washington, widely known for his accommodationist approach as the leader of the Tuskegee Institute, called on northern backers to help finance legal challenges to disfranchisement and segregation. He raised substantial funds and also arranged for representation on some cases, such as the two for Giles in Alabama. He challenged the state's grandfather clause and a citizenship test required for new voters, which was administered in a discriminatory way against blacks.[59]

In its ruling in Giles v. Harris (1903), the United States Supreme Court under Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. effectively upheld such southern voter registration provisions in dealing with a challenge to the Alabama constitution. Its decision said the provisions were not targeted at blacks and thus did not deprive them of rights. This has been characterized as the "most momentous ignored decision" in constitutional history.[60]

Trying to deal with the grounds of the Court's ruling, Giles mounted another challenge. In Giles v. Teasley (1904), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Alabama's disenfranchising constitution. That same year the Congress refused to overturn a disputed election, and essentially sent plaintiffs back to the state courts. Even when black plaintiffs gained rulings in their favor from the Supreme Court, states quickly devised alternative ways to exclude them from the political process. It was not until later in the 20th century that such legal challenges on disfranchisement began to meet more success in the courts.

With the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909, the interracial group based in New York began to provide financial and strategic support to lawsuits on voting issues. What became the NAACP Legal Defense Fund organized and mounted numerous cases in repeated court and legal challenges to the many barriers of segregation, including disfranchisement provisions of the states. The NAACP often represented plaintiffs directly or helped raise funds to support legal challenges. The NAACP also worked at public education, lobbying of Congress, demonstrations, and encouragement of theater and academic writing as other means to reach the public. NAACP chapters were organized in cities across the country, and membership increased rapidly in the South. The American Civil Liberties Union also represented plaintiffs in some disfranchisement cases.

Successful challenges

In Smith v. Allwright (1944), the Supreme Court reviewed a Texas case and ruled against the white primary; the state legislature had authorized the Democratic Party to devise its own rules of operation. The 1944 court ruling was that this was unconstitutional, as the state had failed to protect the constitutional rights of its citizens.

Following the 1944 ruling, civil rights organizations in major cities moved quickly to register black voters. For instance, in Georgia, in 1940 only 20,000 blacks had managed to register to vote. After the Supreme Court decision, the All-Citizens Registration Committee (ACRC) of Atlanta started organizing. By 1947 they and others had succeeded in getting 125,000 black Americans registered, 18.8 percent of those of eligible age.[61] Over the South as a whole, black voter registration steadily increased from less than 3 percent in 1940 to 29 percent in 1960 and over 40 percent in 1964.[62] Nevertheless, gains even in 1964 were minimal in Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana outside Acadiana and southern parts of Georgia, and were limited in most other rural areas.[63]

Each legal victory was followed by white-dominated legislatures' renewed efforts to control black voting through different exclusionary schemes. In the 1940s, Alabama passed a law to give white registrars more discretion in testing applicants for comprehension and literacy. In 1958 Georgia passed a new voter registration act that required those who were illiterate to satisfy "understanding tests" by correctly answering 20 of 30 questions related to citizenship posed by the voting registrar. Blacks had made substantial advances in education, but the individual white registrars were the sole persons to determine whether individual prospective voters answered correctly. In practice, registrars disqualified most black voters, whether they were educated or not. In Terrell County, for instance, which was 64% black in population, after the passage of the act, only 48 black Americans were able to register to vote in 1958.[64]

Civil Rights Movement

The NAACP's steady progress with individual cases was thwarted by southern Democrats' continuing resistance and passage of new statutory barriers to blacks' exercising the franchise. Through the 1950s and 1960s, private citizens enlarged the effort by becoming activists throughout the South, led by many black churches and their leaders, and joined by both young and older activists from northern states. Nonviolent confrontation and demonstrations were mounted in numerous Southern cities, often provoking a violent reactions by white bystanders and authorities. The moral crusade of the Civil Rights Movement gained national media coverage, attention across the country, and growing national demand for change.

Widespread violence against the Freedom Riders in 1961, which was covered by television and newspapers, the murders of activists in Alabama in 1963 gained support for the activists' cause at the national level. President John F. Kennedy introduced civil rights legislation to Congress in 1963 before he was assassinated.

President Lyndon B. Johnson took up the charge. In January 1964, Johnson met with civil rights leaders. On January 8, during his first State of the Union address, Johnson asked Congress to "let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined." On January 23, 1964, the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, prohibiting the use of poll taxes in national elections, was ratified with the approval of South Dakota, the 38th state to do so.

On June 21, 1964, civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi. The three were volunteers aiding in the registration of black voters as part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project. Forty-four days later the Federal Bureau of Investigation recovered their bodies from an earthen dam where they were buried. The Neshoba County deputy sheriff Cecil Price and 16 others, all Ku Klux Klan members, were indicted for the murders; seven were convicted. The investigation also revealed the bodies of several black men, whose deaths had never been revealed or prosecuted by white law enforcement officials.

When the Civil Rights Bill came before the full Senate for debate on March 30, 1964, the "Southern Bloc" of 18 southern Democratic Senators and one Republican Senator, led by Richard Russell (D-GA), launched a filibuster to prevent its passage.[65] Russell said:

We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would have a tendency to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our (Southern) states.[66]

After 57 working days of filibuster, and several compromises, the Senate had enough votes (71 to 29) to end the debate and the filibuster. It was the first time that Southern senators had failed to win with such tactics against civil rights bills. On July 2, President Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[67] The Act prohibited segregation in public places and barred unequal application of voter registration requirements. It did not explicitly ban literacy tests, which had been used to disqualify blacks and poor white voters.

As the United States Department of Justice has stated:

By 1965 concerted efforts to break the grip of state disenfranchisement (sic) had been underway for some time, but had achieved only modest success overall and in some areas had proved almost entirely ineffectual. The murder of voting-rights activists in Philadelphia, Mississippi, gained national attention, along with numerous other acts of violence and terrorism. Finally, the unprovoked attack on March 7, 1965, by state troopers on peaceful marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, en route to the state capitol in Montgomery, persuaded the President and Congress to overcome Southern legislators' resistance to effective voting rights legislation. President Johnson issued a call for a strong voting rights law and hearings began soon thereafter on the bill that would become the Voting Rights Act.[68]

Passed in 1965, this law prohibited the use of literacy tests as a requirement to register to vote. It provided for recourse for local voters to federal oversight and intervention, plus federal monitoring of areas that historically had low voter turnouts to ensure that new measures were not taken against minority voters. It provided for federal enforcement of voting rights. African Americans began to enter the formal political process, most in the South for the first time in their lives. They have since won numerous seats and offices at local, state and federal levels.

See also

- Disfranchisement

- Voter suppression in the United States

- African-American history

- Black suffrage in the United States

- Civil rights movement (1865–1896)

- Civil rights movement (1896–1954)

- List of 19th-century African-American civil rights activists

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

- Jim Crow laws

- Nadir of American race relations

- Judicial aspects of race in the United States

- White backlash

Notes

- Despite the South's excessive representation relative to voting population, the Great Migration resulted in Mississippi losing seats in Congress due to reapportionment following the 1930 and 1950 Censuses, while South Carolina and Alabama also lost Congressional seats after the former Census and Arkansas following the latter.

- Wilson began his political career as Governor of New Jersey in 1910 and remained Governor until he was elected President, but he grew up in a slaveholding family in Virginia.

- Free men of color could vote in North Carolina prior to 1831 if they met property qualifications, but they were barred from voting in 1835 there and elsewhere after fears raised by the Nat Turner slave rebellion of 1831.

- These figures are correct as of the 1900 Presidential election

References

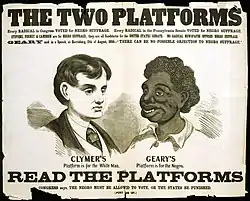

- "The two platforms: About this item". www.loc.gov. Library of Congress. 1866. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Disenfranchise vs. disfranchise". Grammarist. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- World, Debbie Jackson and Hilary Pittman (November 3, 2016). "Throwback Tulsa: Black Oklahomans denied voting rights for decades". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021.

- Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908 (U of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Keele, Luke; Cubbison, William; White, Ismail (2021). "Suppressing Black Votes: A Historical Case Study of Voting Restrictions in Louisiana". American Political Science Review. 115 (2): 694–700. doi:10.1017/S0003055421000034. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 232422468.

- Valelly, Richard M.; The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 134-139 ISBN 9780226845302

- Valelly; The Two Reconstructions; pp. 146-147

- Blinder, Alan; Wines, Michael (9 January 2018). "North Carolina Is Ordered to Redraw Its Congressional Map". The New York Times.

- Wines, Michael (11 January 2018). "Is Partisan Gerrymandering Legal? Why the Courts Are Divided". The New York Times.

- "Chronology of Emancipation during the Civil War". University of Maryland: Department of History.

- Gabriel J. Chin & Randy Wagner, "The Tyranny of the Minority: Jim Crow and the Counter-Majoritarian Difficulty," 43 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 65 (2008)

- Andrews, E. Benjamin (1912). History of the United States. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- "Key Events in the Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes". American President: A Reference Resource. Miller Center. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880–1910, p.104

- Richard H. Pildes, ‘Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon’, Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- Richard H. Pildes, 'Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon', Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, p. 10, Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- Tillman, Benjamin (March 23, 1900). "Speech of Senator Benjamin R. Tillman". Congressional Record, 56th Congress, 1st Session. (Reprinted in Richard Purday, ed., Document Sets for the South in U. S. History [Lexington, MA.: D.C. Heath and Company, 1991], p. 147.). pp. 3223–3224.

- ‘COMMITTEE AT ODDS ON REAPPORTIONMENT’, The New York Times, 20 Dec 1900, accessed 10 Mar 2008

- W.E.B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1868–1880, New York: Oxford University Press, 1935; reprint, New York: The Free Press, 1998

- Michael Perman.Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908. Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press, 2001, Introduction

- 1878–1895: Disenfranchisement (sic), Southern Education Foundation Archived 2008-06-07 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 16 Mar 2008

- J. Morgan Kousser.The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974

- Glenn Feldman, The Disfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136

- Mickey, Robert; Paths Out of Dixie: The Democratization of Authoritarian Enclaves in America's Deep South, 1944-1972, p. 87 ISBN 1400838789

- Historical Census Browser, 1900 Federal Census, University of Virginia Archived 2007-08-23 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 15 Mar 2008

- Monnet, Julien C. (1912). "The Latest Phase of Negro Disfranchisement". Harvard Law Review. 26 (1): 42–63. doi:10.2307/1324271. JSTOR 1324271.

- Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", 2000, p.12, accessed 10 Mar 2008

- "Fusion Politics". northcarolinahistory.org. North Carolina History Project. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- "The North Carolina Election of 1898 · UNC Libraries". www.lib.unc.edu. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Richard H. Pildes, 'Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon', 2000, pp.12 and 27 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- Albert Shaw, The American Monthly Review of Reviews, Vol.XXII, Jul-Dec 1900, p.274

- Richard H. Pildes, ‘Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon’, Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, pp. 12-13

- Historical Census Browser, 1900 US Census, University of Virginia Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, accessed 15 Mar 2008

- Richard H. Pildes, 'Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon', 2000, p.12 and 27, Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- "Virginia's Constitutional Convention of 1901–1902". Virginia Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2006-10-02. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- Dabney, Virginius (1971). Virginia, The New Dominion. University Press of Virginia. pp. 436–437. ISBN 978-0-8139-1015-4.

- Smith, C. Fraser; Here Lies Jim Crow: Civil Rights in Maryland; p. 66 ISBN 0801888077

- Shufelt, Gordon H.; 'Jim Crow among strangers: The growth of Baltimore's Little Italy and Maryland's disfranchisement campaigns'; Journal of American Ethnic History; vol. 19, issue 4 (Summer 2000), pp. 49-78

- Klotter, Jeames C.; Kentucky: Portrait in Paradox, 1900-1950; pp. 196-197 ISBN 0916968243

- "Historical Barriers to Voting", in Texas Politics, University of Texas, accessed 4 November 2012.

- "Atlanta in the Civil Rights Movement". www.atlantahighered.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Rogers, George C. and C. James Taylor Jr. (1994). A South Carolina Chronology 1497–1992. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-87249-971-3.

- Holt, Thomas (1979). Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- "Judge Goff Reversed". Richmond Planet. Richmond, Virginia. June 22, 1895. p. 2. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- Curtis, Benjamin Robbins (Justice). "Dred Scott v. Sandford, Curtis dissent". Legal Information Institute at Cornell Law School. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- Richard M. Valelly, The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004, p.141

- "Lane v. Wilson 307 U.S. 268 (1939)". justia.com. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Texas Politics: Historical Barriers to Voting, accessed 11 Apr 2008 Archived April 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Keyssar, Alexander; The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States, Basic Books, 2000/2009, p. 86 ISBN 0465005020

- Wendy Hazard, 'Thomas Brackett Reed, Civil Rights, and the Fight for Fair Elections,' Maine History, March 2004, Vol. 42 Issue 1, pp 1–23

- Richard H. Pildes, 'Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon', Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, pp.19-20, Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- Richard H. Pildes, ‘Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon’, Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, pp.20-21 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- Times, Special to The New York (December 6, 1920). "DEMANDS INQUIRY ON DISFRANCHISING; Representative Tinkham Aims to Enforce 14th and 15th Articles of Constitution. ASKS REAPPORTIONMENT House Resolution Will Point Out Disparity Between Southern Membership and Votes Cast". The New York Times. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- Smith, J. Douglas; On Democracy's Doorstep: The Inside Story of How the Supreme Court Brought "One Person, One Vote" to the United States; pp. 4-18 ISBN 0809074249

- See Rodden, Jonathan A.; ‘The Long Shadow of the Industrial Revolution: Political Geography and the Representation of the Left’

- Day, Davis S. (Winter 1980). "Herbert Hoover and Racial Politics: The De Priest Incident". Journal of Negro History. 65 (1): 6–17. doi:10.2307/3031544. JSTOR 3031544. S2CID 149611666.

- August Meier, August, and Elliott Rudwick. 'The Rise of Segregation in the Federal Bureaucracy, 1900–1930.' Phylon (1960) 28.2 (1967): 178-184. in JSTOR

- Richard H. Pildes, ‘Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon’, Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, p. 21 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- Richard H. Pildes, 'Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon', Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, 2000, p.32 Accessed 10 Mar 2008

- Chandler Davidson and Bernard Grofman, Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994, p.70

- Beyerlein, Kraig and Andrews, Kenneth T.; ‘Black Voting during the Civil Rights Movement: A Micro-Level Analysis’; Social Forces, volume 87, No. 1 (September 2008), pp. 65-93

- See Subcommittee No. 5; Committee on the Judiciary. House of Representatives; 1965 Voting Rights Act, pp. 4, 139-201

- Davidson and Grofman (1994), Quiet Revolution in the South, p. 71

- "Major Features of the Civil Rights Act of 1964". Congresslink.org. Archived from the original on 2014-12-06. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- "Civil Rights Act of 1964". Spartacus-Educational.com. Archived from the original on 2010-05-16. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- "Civil Rights during the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson". LBJ Library and Museum. Archived from the original on 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- "Introduction To Federal Voting Rights Laws". United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 2007-03-04. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

Further reading

- Brown, Nikki L.M., and Barry M. Stentiford, eds. The Jim Crow Encyclopedia (Greenwood, 2008)

- Feldman, Glenn. The disfranchisement myth: Poor whites and suffrage restriction in Alabama (U of Georgia Press, 2004).

- Grantham, Dewey W. 'Tennessee and Twentieth-Century American Politics,' Tennessee Historical Quarterly 54, no 3 (Fall 1995): 210+ online

- Grantham, Dewey W. "Georgia Politics and the Disfranchisement of the Negro." Georgia Historical Quarterly 32.1 (1948): 1-21. online

- Graves, John William. "Negro Disfranchisement in Arkansas." Arkansas Historical Quarterly 26.3 (1967): 199-225. online

- Korobkin, Russell. "The Politics of Disfranchisement in Georgia." Georgia Historical Quarterly 74.1 (1990): 20-58.

- Moore, James Tice. "From Dynasty to Disfranchisement: Some Reflections about Virginia History, 1820-1902." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 104.1 (1996): 137-148. online

- Perman, Michael. Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908 (2001).

- Rable, George C. 'The South and the Politics of Antilynching Legislation, 1920–1940.' Journal of Southern History 51.2 (1985): 201-220.

- Redding, Kent. Making Race, Making Power: North Carolina's Road to Disfranchisement (U of Illinois Press, 2003).

- Shufelt, Gordon H. "Jim Crow among strangers: The growth of Baltimore's Little Italy and Maryland's disfranchisement campaigns." Journal of American Ethnic History (2000): 49-78. online

- Valelly, Richard M. The two reconstructions: The struggle for black enfranchisement (U of Chicago Press, 2009).

- Woodward, C. Vann. "Tom Watson and the Negro in agrarian politics." Journal of Southern History 4.1 (1938): 14-33. online