Dreadlocks

Dreadlocks, also known as locs or dreads, are rope-like strands of hair formed by matting or braiding hair.[2]

Origins

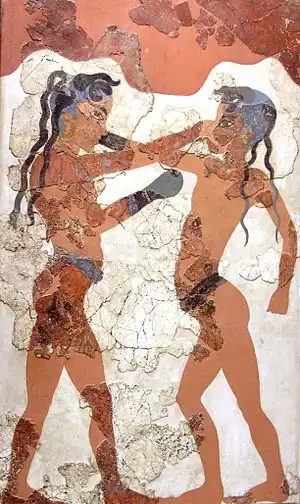

According to Sherrow in Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History, dreadlocks date back to ancient times in various cultures. In ancient Egypt, Egyptians wore locked hairstyles and wigs appeared on bas-reliefs, statuary and other artifacts.[6] Mummified remains of Egyptians with locked wigs have also been recovered from archaeological sites.[7] According to Dr. Delongoria, braided and locked hair was worn by people in the Sahara desert since 3,000 BC. Dreadlocks was also worn by followers of Abrahamic religions. For example, Ethiopian Coptic priests adopted dreadlocks as a hair style before the fifth century BC (400 or 500 BC). Locked hair was practiced by some ethnic groups in East, Central, and Southern Africa.[8][9][10] Other earliest known possible depictions of dreadlocks date back as far as 1600–1500 BCE in the Minoan Civilization, centred in Crete (now part of Greece).[4] Frescoes discovered on the Aegean island of Thera (modern Santorini, Greece) depict individuals with long braided hair or long dreadlocks.[3][4]

During the Bronze and Iron Ages, many peoples in the Near East, Anatolia, Caucasus, East Mediterranean and North Africa were depicted in art with braided, plaited, twisted or curled hair and beards, Similarly in Europe with peoples such as Bronze and Iron Age Greeks, Minoans, Dacians, Celts and Etruscans. However, braids, twists and plaits are not dreadlocks, and it is not always possible to tell from these images which are being depicted.[11][12]

Etymology

The history of the name "dreadlocks" is unclear. Some authors trace the term to the Rastafarians, coining it as a reference to their wearing the hairstyle as a sign of their "dread" (or fear) of God.[13] However, Rastafari did not develop in Jamaica until the 1930s. According to Lori L. Tharps, hair historian and coauthor of Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America, "the modern understanding of dreadlocks is that the British, who were fighting Kenyan warriors (during colonialism in the late 19th century), encountered the warriors' locs and found them 'dreadful', thus coining the term 'dreadlocks'."[14]

History

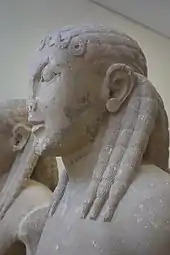

In Ancient Greece, kouros sculptures from the archaic period depict men possibly wearing dreadlocks.[15][16][17][18]

Pre-Columbian Aztec priests were described in Aztec codices (including the Durán Codex, the Codex Tudela and the Codex Mendoza) as wearing their hair untouched, allowing it to grow long and matted.[19] Bernal Diaz del Castillo records:

here were priests with long robes of black cloth ... The hair of these priests was very long and so matted that it could not be separated or disentangled, and most of them had their ears scarified, and their hair was clotted with blood.

In Senegal, the Baye Fall, followers of the Mouride movement, a Sufi movement of Islam founded in 1887 AD by Shaykh Aamadu Bàmba Mbàkke, are famous for growing dreadlocks and wearing multi-colored gowns.[20] Cheikh Ibra Fall, founder of the Baye Fall school of the Mouride Brotherhood, popularized the style by adding a mystic touch to it. Warriors among the Fulani, Wolof and Serer in Mauritania, and Mandinka in Mali were known for centuries to have worn cornrows when young and dreadlocks when old. Larry Wolff in his book Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of Enlightenment mentions that in Poland, for about a thousand years, some people wore a matted hairstyle similar to that of some Iranic Scythians. Zygmunt Gloger in his Encyklopedia staropolska mentions that the Polish plait (plica polonica) hairstyle was worn by some people in the Pinsk region and the Masovia region at the beginning of the 19th century. The Polish plait can vary between one large plait and multiple plaits that resemble dreadlocks.[21]

Dreadlocks are also worn by some Rastafarians from the late 20th century onwards, who believe they represent a biblical hair style worn as a symbol of devotion by the Jewish Nazirites of West Asia, as described in Numbers 6:1–21.[22]

By culture

Locks (like braids and plaits) have been worn for various reasons in many cultures and ethnic groups around the world throughout history. Their use has also been raised in debates about cultural appropriation.[23][24] White people wearing dreadlocks continues to be debated and seen as cultural appropriation. In the book, White Out: A Guidebook for Teaching and Engaging with Critical Whiteness Studies, has several essays written by college students explaining white people utilizing the cultures of people of color. For example, when white people wear Mohawks (a Native American hairstyle) or dreadlocks they do so without understanding the historical and cultural significance a hairstyle has to that culture and the discrimination people of color experience when they practice their culture, and are not allies to the struggles of Brown and Black people.[25] In Texas public schools, dreadlocks and traditional Native American hairstyles are prohibited especially to boy students because long braided hair is considered unmasculine according to white western standards of masculinity which defines masculinity as "short, tidy hair." Black and Brown boys are stereotyped and receive negative treatment and negative labeling for wearing dreadlocks, cornrows, and long braids. Non-white students are prohibited from practicing their traditional hairstyles that are a part of their culture.[26]

The policing of Black hairstyles also occurs in London, England. Black students in England are prohibited from wearing natural hairstyles such as dreadlocks, Afros, braids, twists, and other African and Black hairstyles. Black students are suspended from school, are stereotyped, and receive negative treatment from white teachers.[27]

Africa

In West Africa the water spirit, Mami Wata, is said to have long locked hair.[28] West African spiritual priests called, Dada, that venerated Mami Wata wore dreadlocks in her honor as spiritual consecrations.[29] The word Dada is given to children in Nigeria born with dreadlocks. Some Yoruba people believe children born with dreadlocks have innate spiritual powers, and cutting their hair might cause serious illness. Only the child's mother can touch their hair. "Dada children are believed to be young gods, they are often offered at spiritual alters for chief priests to decide their fate. Some children end up become spiritual healers and serve at the shrine for the rest of their lives." If their hair is cut, it must be cut by a chief priest and placed in a pot of water with herbs, and the mixture is used to heal the child if they get sick.[30] Dada children is a traditional belief in Nigeria, however due to colonialism some Nigerians do not hold positive views about dreadlocks. Dreadlocks are viewed in a negative light due to their stereotypical association with gangs and criminal activity; men with dreadlocks face profiling from Nigerian police.[31][32] In Ghana among the Ashanti people, okomfo priests are identified by their dreadlocks. They are not allowed to cut their hair and must allow the hair to matt and loc naturally.[33][34] Other spiritual people in Southern Africa who wear dreadlocks are Sangomas. Sangomas wear red and white beaded dreadlocks to connect to ancestral spirits. Two African men were interviewed explaining why they chose to wear dreadlocks. "One – Mr Ngqula – said he wore his dreadlocks to obey his ancestors’ call, given through dreams, to become a “sangoma” in accordance with his Xhosa culture. Another – Mr Kamlana – said he was instructed to wear his dreadlocks by his ancestors and did so to overcome 'intwasa', a condition understood in African culture as an injunction from the ancestors to become a traditional healer, from which he had suffered since childhood."[35][36]

Maasai warriors are known for their long, thin, red dreadlocks, dyed with red root extracts or red ochre.[37] The Himba women in Namibia are also known for their red colored dreadlocks. Himba women use red earth clay mixed with butter and roll their hair with the mixture. They use natural moisturizers to maintain the health of their hair. Historians noted West and Central African people braid their hair to signify age, gender, rank and role in society, and ethnic affiliation. It is believed braided and locked hair provides spiritual protection, connects people to the spirit of the earth, bestows spiritual power, and enables people to communicate with the gods and spirits.[38][39][40] During the Atlantic-slave trade, European slave traders shaved the heads of Africans before they boarded slave ships to strip the Africans of their identity.[41] In another source, some Africans heads were not shaved before they boarded slave ships heading to the Americas. Enslaved Africans spent months in slave ships and their hair matted into dreadlocks that European slave traders called "dreadful."[42]

In the Black Diaspora, Black people loc their hair to have a stronger connection to the spirit world and receive messages from spirits. It is believed locked hair are antennas making the wearer receptive to spiritual messages.[43]

Australia

Some Indigenous Australians of North West and North Central Australia, as well as the Gold Coast region of Eastern Australia, have historically worn their hair in a locked style, sometimes also having long beards that are fully or partially locked. Traditionally, some wear the dreadlocks loose, while others wrap the dreadlocks around their heads, or bind them at the back of the head.[44] In North Central Australia, the tradition is for the dreadlocks to be greased with fat and coated with red ochre, which assists in their formation.[45]

Buddhism

Within Tibetan Buddhism and other more esoteric forms of Buddhism, locks have occasionally been substituted for the more traditional shaved head. The most recognizable of these groups are known as the Ngagpas of Tibet. For Buddhists of these particular sects and degrees of initiation, their locked hair is not only a symbol of their vows but an embodiment of the particular powers they are sworn to carry.[46] 1.4.15 of the Hevajra Tantra states that the practitioner of particular ceremonies "should arrange his piled up hair" as part of the ceremonial protocol.[47] Archeologists found a statue of a male deity, Shiva, with dreadlocks in Stung Treng province in Cambodia.[48] In a sect of tantric Buddhism some initiates wear dreadlocks.[49][50] The sect of tantric Buddhism wear initiates wear dreadlocks is called weikza and Passayana or Vajrayana Buddhism. This sect of Buddhism is practiced in Burmese. They spend years in the forest with this practice and when they return to the temples they should not shave their heads to reintegrate.[51]

Hinduism

The practice of Jaṭā (dreadlocks) is practiced in modern day Hinduism,[52][53][54] most notably by Sadhus who follow Śiva.[55][56] The Kapalikas, first commonly referenced in the 6th century CE, were known to wear Jaṭā[57] as a form of deity imitation of the deva Bhairava-Śiva.[58] Shiva is often depicted with dreadlocks.

In a village in Pune, Savitha Uttam Thorat, some women hesitate to cut their long dreadlocks because it is believed it will cause misfortune or bring down divine wrath. Dreadlocks practiced by the women in this region of India are believed to be possessed by the Goddess Yellamma. Cutting off the hair is believed to bring misfortune onto the woman, because having dreadlocks is considered to be a gift from Goddess Yellama (other names for this Goddess is Renuka).[59] Some of the women have long and heavy dreadlocks that puts a lot of weight on their necks causing pain and limited mobility.[60][61] Some in local government and police in the Maharashtra region demand the women to cut their hair, because the religious practice of Yellamma forbids women from washing and cutting their dreadlocks causing health issues.[62]

Rastafari

Rastafari movement dreadlocks are symbolic of the Lion of Judah, and were inspired by the Nazarites of the Bible.[63] When reggae music, which espoused Rastafarian ideals, gained popularity and mainstream acceptance in the 1970s, thanks to Bob Marley's music and cultural influence, dreadlocks (often called "dreads") became a notable fashion statement worldwide, and have been worn by prominent authors, actors, athletes and rappers.[64][65]

In sports

Dreadlocks have become a popular hairstyle among professional athletes. However, some athletes are discriminated against and were forced to cut their dreadlocks. For example, in December of 2018 a Black high school wrestler in New Jersey was forced to cut his dreadlocks 90 seconds before his match that sparked a Civil Rights case leading to passage of the CROWN act in 2019.[66]

In professional American football, the number of players with dreadlocks has increased ever since Al Harris and Ricky Williams first wore the style during the 1990s. In 2012, about 180 National Football League players wore dreadlocks. A significant number of these players are defensive backs, who are less likely to be tackled than offensive players. As per the NFL's rulebook, a player's hair is considered part of their "uniform", meaning the locks are fair game when attempting to bring them down. [67]

In the NBA there has been controversy over the Brooklyn Nets guard Jeremy Lin, an Asian-American who garnered mild controversy over his choice of dreadlocks. Former NBA player Kenyon Martin accused Lin of appropriating African-American culture in a since-deleted social media post, after which Lin pointed out that Martin has multiple Chinese characters tattooed on his body. [68]

David Diamante the American Boxing ring announcer of Italian American heritage sports prominent dreadlocks.

In the US

On 3 July 2019, California became the first US state to prohibit discrimination over natural hair. Governor Gavin Newsom signed the CROWN Act into law, banning employers and schools from discriminating against hairstyles such as dreadlocks, braids, afros, and twists.[69] Likewise, later in 2019, Assembly Bill 07797 became law in New York state; it "prohibits race discrimination based on natural hair or hairstyles".[70][71] The word used to describe discrimination based on hair is called by scholars, hairism. After passage of the CROWN act, hairism continues. Some Black people are fired from work or are not hired because of their dreadlocks.[72]

Guinness Book of World Records

On 10 December 2010, the Guinness Book of World Records rested its "longest dreadlocks" category after investigation of its first and only female title holder, Asha Mandela, with this official statement:

Following a review of our guidelines for the longest dreadlock, we have taken expert advice and made the decision to rest this category. The reason for this is that it is difficult, and in many cases impossible, to measure the authenticity of the locks due to expert methods employed in the attachment of hair extensions/re-attachment of broken off dreadlocks. Effectively the dreadlock can become an extension and therefore impossible to adjudicate accurately. It is for this reason Guinness World Records has decided to rest the category and will no longer be monitoring the category for longest dreadlock.[73]

Notes

- Hair: Styling, Culture and Fashion. University of Michigan [Michigan]: Bloomsbury Academic. 2009. ISBN 9781845207922.

His jata (dreadlocks) are elegantly styled, and the source of the Ganges issues from his topknot. In the background are the Himalayas where Shiva performs his austerities.

- Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (11th ed.). [ ]: Merriam-Webster. 2004. pp. 380. ISBN 9780877798095.

dread-lock \'dred-,lak\ n (I960) 1 : a narrow ropelike strand of hair formed by matting or braiding 2 pi : a hairstyle consisting of dreadlocks — dread-locked \-,lakt\ adj

- Poliakoff, Michael B. (1987). Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture. Yale University Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780300063127.

The boxing boys on a fresco from Thera (now the Greek island of Santorini), also 1500 B.C.E., are less martial with their jewelry and long braids, and it is hard to imagine that they are engaged in a hazardous

- Blencowe, Chris (2013). YRIA: The Guiding Shadow. Sidewalk Editions. p. 36. ISBN 9780992676100.

... Archaeologist Christos Doumas, discoverer of Akrotiri, wrote: "Even though the character of the wall-paintings from Thera is Minoan, ... the boxing children with dreadlocks, and ochre-coloured naked fishermen proudly displaying their abundant hauls of blue and yellow fish.

- Bloomer, W. Martin (2015). A Companion to Ancient Education. John Wiley & Sons. p. 31. ISBN 9781119023890.

Figure 2.1b Two Minoan boys with distinctive hairstyles, boxing. Fresco from West House, Thera (Santorini), ca. 1600–1500 bce (now in the National Museum, Athens).

- "Image of Egyptian with locks". freemaninstitute.com. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Egyptian Museum -"Return of the Mummy. Archived 2005-12-30 at the Wayback Machine Toronto Life - 2002." Retrieved 01-26-2007.

- Sherrow, Victoria (2023). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 140. ISBN 9781440873492.

- Delongoria (2018). "Misogynoir: Black Hair, Identity Politics, and Multiple Black Realities" (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. 12 (8): 40. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Dreads. Artisan Books. 1999. p. 22. ISBN 9781579651503.

- "The history of hair, hair styles through the ages". Archived from the original on 2007-04-26. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- Gabbara, Princess (2016-10-18). "The History of Dreadlocks". EBONY. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- "Twisted Locks of Hair: The Complicated History of Dreadlocks". Esquire. 5 October 2022.

- "Why I Don't Refer to My Hair as 'Dreadlocks'". Vogue. 30 March 2023.

- Steves, Rick (2014). Athens and the Peloponnese. Avalon Travel. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-61238-060-5.

- Jenkins, Ian. "Archaic Kouroi in Naucratis: The Case for Cypriot Origin". The American Journal of Cardiology. [JSTOR Arts & Sciences II Collection]: American Journal of Archaeology, v105 n2 (20010401): 168–175. ISSN 0002-9114.

The hair in both is filleted into a series of fine dreadlocks, tucked behind the ears and falling on each shoulder and down the back. A narrow fillet passes around the forehead and disappears behind the ears. ... Two are in the British Museum (fig. 17) and another in Boston (fig. 18). These three could have been carved by the same hand. Distinctive points of comparison include the dreadlocks; high, prominent chest without division; sloping shoulders; manner of showing the arms by the side...the torso of a kouros, again in Boston (fig. 19), should probably also be assigned to this group.

- Sherrow, Victoria (2023). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781440873492.

- Dreads. Artisan Books. 1999. ISBN 9781579651503.

- Berdán, Frances F. and Rieff Anawalt, Patricia (1997). The Essential Codex Mendoza. London, England: University of California Press. pp 149.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-27. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Zeitreisen - Vom Einimpfen und Auskampeln".

- "Dreadlocks in History - How Dreadlocks Work". HowStuffWorks. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Students are claiming the white man harassed over his dreadlocks isn't telling the full story". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- Ring, Kyle. "Twisted Locks of Hair: The Complicated History of Dreadlocks". Esquire. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Beech, Jennifer (2020). White Out: A Guidebook for Teaching and Engaging with Critical Whiteness Studies. BRILL. p. 92. ISBN 9789004430297.

- Banks, Patricia (2023). "No Dreadlocks Allowed: Race, Hairstyles, and Exclusion in Schools". Multicultural Perspectives. 25 (1). Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- Joseph-Salibury; Connelly (2018). "'If Your Hair Is Relaxed, White People Are Relaxed. If Your Hair Is Nappy, They're Not Happy': Black Hair as a Site of 'Post-Racial' Social Control in English Schools". Social Science. 7 (11). Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- Dreads. Artisan Books. 1999. p. 22. ISBN 9781579651503.

- Kasfir, Sidney (1994). "Reviewed Works: Mammy Water: In Search of the Water Spirits in Nigeria by Sabine Jell-Bahlsen; Mami Wata: Der Geist der Weissen Frau by Tobias Wendl, Daniela Weise". African Arts. 27 (1): 80. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Talks, Abena. "These Special Nigerian Children are Born with Natural Dreadlocks that Must Never be Shaved off These children are believed to be mini gods". Medium. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- "'People with locs are seen as miscreants'". BBC News.

- Agwuele, Augustine (2016). The Symbolism and Communicative Contents of Dreadlocks in Yorubaland. Springer. ISBN 9783319301860.

- Rhodes, Jerusha (1996). "Fufuo, Dreadlocks, Chickens and Kaya: Practical Manifestations of Traditional Ashanti Religion". African Diaspora. 28: 18–19. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Cartwright, Angie. "The Dreadlocks". Afrostyle Magazine. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Ramalapa, Jedidiah (2021). Soweto to Beirut. African Sun Media. p. 119. ISBN 9780620931816.

- De Vos, Pierre. "Putting the 'dread' into 'dreadlocks'". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- Fihlani, Pumza (27 February 2013). "South Africa's dreadlock thieves". BBC News. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Davies, Monika (2017). Surprising Things We Do for Beauty 6-Pack. Teacher Created Materials. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9781493837267.

- "The History of Hair". The African American Museum of Iowa. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Delongoria, Maria (2018). "Misogynoir: Black Hair, Identity Politics, and Multiple Black Realities" (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. 12 (8): 40. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- "Colonialism, Hair, and Enslavement". African American Museum of Iowa. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Sherrow, Victoria (2023). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 140. ISBN 9781440873492.

- Consentino; Fabius (2001). "Body Talk". African Arts. 34 (2): 9. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Withnell, John G. (1901). The Customs And Traditions Of The Aboriginal Natives Of North Western Australia. ROEBOURNE. p. 14.

- Baldwin Spencer and F. J. Gillen (1899). The Native Tribes of North Central Australia. London: Macmillan.

- Bogin, Benjamin (2008). "The Dreadlocks Treatise: On Tantric Hairstyles in Tibetan Buddhism". History of Religions. 48 (2): 85–109. doi:10.1086/596567. JSTOR 10.1086/596567. S2CID 162206598.

- Snellgrove, David. The Hevajra Tantra: A Critical Study. vol 1. Oxford University Press. 1959.

- Saran, Shyam (2018). Cultural and Civilisational Links between India and Southeast Asia: Historical and Contemporary Dimensions. Springer. p. 265. ISBN 9789811073175.

- Wedemeyer, Christian (2014). Making Sense of Tantric Buddhism: History, Semiology, and Transgression in the Indian Traditions. Columbia University Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780231162418.

- Bogin, Benjamin (2018). "The Dreadlocks Treatise: On Tantric Hairstyles in Tibetan Buddhism". History of Religions. 48 (2): 85–95. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- Schmidt-Leukel; Grosshans; Krueger (2021). Ethnic and Religious Diversity in Myanmar: Contested Identities. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 9781350187412.

- "Why Some Indian Women Are Terrified of Chopping off Their Dreadlocks, Even Though They Can't Move Their Necks". Vice. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- Rattanpal, Divyani (2015-10-06). "Hair and Shanti: What Hair Means to Indians". TheQuint. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- "What Sadhus and Sadhvis at Kumbh Told Me About Their Long and Important Dreadlocks". News 18. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- "What Sadhus and Sadhvis at Kumbh Told Me About Their Long and Important Dreadlocks". 3 February 2019.

- Hays, Jeffrey. "SADHUS, HINDU HOLY MEN | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- Lorenzen, David (1972). The Kapalikas and kalamukhas: Two Lost Saivite Sects. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. pp. 4, 6, 14, 21–23, 41–42, 47. ISBN 0-520-01842-7.

- Lorenzen, David (1972). The Kapalikas and kalamukhas: Two Lost Saivite Sects. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. pp. 4, 85. ISBN 0-520-01842-7.

- Varde, Abhijit (1997). Daughters of Maharashtra: Portraits of Women who are Building Maharastra : Interviews and Photographs. University of Virginia. p. 12.

- Chakraborty, Reshmi. "Why Some Indian Women Are Terrified of Chopping off Their Dreadlocks, Even Though They Can't Move Their Necks". Vice. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- Torgaltar, Varsha. "This Maharashtra Group is Cutting off Superstition – One Dreadlock at a Time". The Wire. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- Kassam, Zayn (2017). Women and Asian Religions. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9798216166139.

- "Dare to dread". The Guardian. 2003-08-23. Retrieved 2022-11-11.

- "19 Celebs Slaying In Beautiful Locs". Essence. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- Kuumba, M.; Ajanaku, Femi (1998). "Dreadlocks: The Hair Aesthetics of Cultural Resistance and Collective Identity Formation". Mobilization: An International Quarterly. 3 (2): 227–243. doi:10.17813/maiq.3.2.nn180v12hu74j318.

- Brown, Nadia; Lemi, Danielle (2021). Sister Style: The Politics of Appearance for Black Women Political Elites. Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780197540596.

- "Matz: NFL players embracing long hair". ESPN.com. 29 December 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- "Jeremy Lin's dreadlocks have led to all kinds of comments — even Lil B's support".

- "California bans racial discrimination based on hair in schools and workplaces". JURIST. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- "New York bans discrimination against natural hair". The Hill. 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2019-07-18.

- Lee; Nambudiri (2021). "The CROWN act and dermatology: Taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 84 (4). Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- Donahoo (2021). "Why We Need a National CROWN Act". The Body Politic: Women’s Bodies and Political Conflict. 10 (2). Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- "Longest Dreadlock Record – Rested". Archived from the original on 2011-10-05.

References

- Kroemer, K. (2001). Ergonomics: How to Design for Ease and Efficiency (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0137524781.

- Tacitus, Publius (or Gaius) Cornelius. De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae.

External links

Media related to Dreadlocks at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dreadlocks at Wikimedia Commons- Dreadlocks Story – Documentary by Linda Aïnouche

- Guardian article

The dictionary definition of dreadlocks at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of dreadlocks at Wiktionary

.svg.png.webp)