Ria

A ria (/ˈriːə/;[1] Galician: ría, feminine noun derived from río, river) is a coastal inlet formed by the partial submergence of an unglaciated river valley. It is a drowned river valley that remains open to the sea.

_V2.jpg.webp)

Definitions

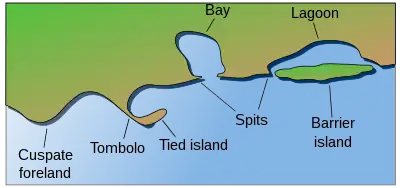

Typically rias have a dendritic, treelike outline although they can be straight and without significant branches. This pattern is inherited from the dendritic drainage pattern of the flooded river valley. The drowning of river valleys along a stretch of coast and formation of rias results in an extremely irregular and indented coastline. Often, there are naturally occurring islands, which are summits of partly submerged, pre-existing hill peaks. (Islands may also be artificial, such as those constructed for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.)

A ria coast is a coastline having several parallel rias separated by prominent ridges, extending a distance inland.[2][3][4] The sea level change that caused the submergence of a river valley may be either eustatic (where global sea levels rise), or isostatic (where the local land sinks). The result is often a very large estuary at the mouth of a relatively insignificant river (or else sediments would quickly fill the ria). The Kingsbridge Estuary in Devon, England, is an extreme example of a ria forming an estuary disproportionate to the size of its river; no significant river flows into it at all, only a number of small streams.[4]

The word ria comes from Galician ría which comes from río (river). Rias are present all along the Galician coast in Spain. As originally defined, the term was restricted to drowned river valleys cut parallel to the structure of the country rock that was at right angles to the coastline. However the definition of ria was later expanded to other flooded river valleys regardless of the structure of the country rock.

For a time European geomorphologists[5] considered rias to include any broad estuarine river mouth, including fjords. These are long narrow inlets with steep sides or cliffs, created in a valley carved by glacial activity. In the 21st century, however, the preferred usage of ria by geologists and geomorphologists is to refer solely to drowned unglaciated river valleys. It therefore excludes fjords by definition, since fjords are products of glaciation.[2][3][4]

Locations

Europe

- Portugal: has no rias as such: the Ria de Aveiro in Aveiro, and Ria Formosa in Eastern Algarve[6] are actually lagoons.

- Atlantic coast of Spain

- Galicia:

- The Rías Baixas, including the Ria of Vigo, Ria of Pontevedra, Ría de Arousa, Ria of Muros and Noia, Ria of Corcubion, Cee and Ría de Aldán.

- The Rías Altas, including the Ria of Corunna, Ria of Camariñas, Ria of Corme, Ria of Lires, Ria of Ares and Betanzos, Ria of Cedeira, Ria of O Barqueiro, Ria of Ferrol, Ria of Ortigueira, Ria of Viveiro, Ria of Foz and Ria of Ribadeo.

- Asturias: Ria of Avilés, Ria of Ribadeo, Ria of Navia, Ria of Villaviciosa, Ria of Ribadesella, Ria of Llanes, Ria of Tina Mayor.

- Cantabria: Ria of Tina Mayor, Ria of Tina Menor, Ría de San Vicente de la Barquera, Ría of la Rabia, Ría of San Martín de la Arena, Ría of Mogro, Ría of Solía, Ría of Carmen, Ría of Boo, Ría of Tijero, Ría of Cubas, Ría de Ajo, Ría of Cabo Quejo, Ría of Treto, Ría of Oriñón.

- Basque Country: Ria of Bilbao, mouth of the rivers Nervión, Ibaizabal, and Cadagua.

- Andalusia: Ria of Carreras, Ria of Huelva at the mouth of the rivers Odiel and Tinto.

- Galicia:

- Brittany: The rias in northern Brittany are called Abers: Aber Wrac'h (48.599807°N 4.549376°W), Aber Benoît (48.562747°N 4.579905°W), Aber Ildut (48.472649°N 4.749602°W) etc. The Roadstead of Brest also includes several rias.

- Ireland: Bantry Bay, on the southwest coast of Ireland, is an example of an Irish ria.

- Wales: Milford Haven Waterway in Pembrokeshire is a ria.

- England: The south coast of England is a submergent coastline which contains many rias, including Southampton Water, Poole Harbour, the estuary of the River Medina on the Isle of Wight, the estuaries of the Exe, Teign and Dart, then Kingsbridge Estuary, Plymouth Sound in Devon, and the estuaries of the River Fowey, River Fal and Helford River in Cornwall. On the north coast is the River Camel and the River Taw. In Essex are the River Blackwater and River Crouch.

- Italy: The Fiordo di Furore on the Amalfi Coast in Campania is a ria, despite its name.

- Malta: Grand Harbour and Marsamxett Harbour

- Croatia: Porto Quieto, Lim, Raša, Novsko Ždrilo, Karinsko Ždrilo, Zrmanja, Krka, Morinje, Ploče, Ston, Slano, Zaton.

- Montenegro: The Bay of Kotor

- Turkey: Bosporus, Golden Horn.

Africa

- Kenya: Kilindini Harbour, which is a deep channel between Mombasa island and South Coast mainland, is a ria.

Asia

- Sanriku Coast: North Japan, east coast of Honshū Island (main island). Sendai city, Miyagi Prefecture and Iwate Prefecture are included.

- Ago Coast in Shima (Mie Prefecture) is a Ria coast, well known for its pearls.

- Seto Inland Sea, seperating Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku.

- Coasts on western, southern sides of the Korean Peninsula: Rias formed by sea level rising after Ice Age.

- The Chinese east coast, from the Guangdong province (Hong Kong coastlines included) to Shanghai.

- The Musandam Peninsula in Oman, comprising the southern shore of the Strait of Hormuz.

Oceania

- Papua New Guinea: Rias formed by eroded volcanic lava flow are found all around the town of Tufi at Cape Nelson, in Papua New Guinea's Oro Province.

- Australia: The east coast of Australia features several rias around Sydney, including Georges River, Port Hacking, and Port Jackson, which includes Sydney Harbour. There are many examples in Western Australia, including the Swan River around Perth and several rivers in the west Kimberley region.

- New Zealand: Rias of various scales abound on the eastern shores of the upper North Island. On the west coast, in contrast, they are fewer but larger. Kaipara Harbour is the country's largest, and the Hokianga Harbour, further north, is of historical significance to the native Māori people. The Marlborough Sounds at the northern tip of the South Island form a large network of rias.

- Hawaii: Pearl Harbor on Oahu is a ria, with the branches of West Loch, Middle Loch, East Loch, and Southeast Loch formed by the submerged drainages of Waikele, Waiau, Waimalu, and Hālawa streams respectively.

North America

- United States: Narragansett Bay, New York Harbor, Delaware Bay, Indian River Bay, the Chesapeake Bay, and Charleston Harbor are rias on the East Coast. Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor in Washington and San Francisco Bay in California on the West Coast are also rias.

- Canada: Charlottetown Harbour, Prince Edward Island

South America

- Argentina: Patagonia has the Deseado ria, on the coast of Santa Cruz Province, on the Atlantic Ocean. Also, the "bay" that is Bahía Blanca is a ría.

Consequences

The funnel-like shape of rias can amplify the effects of tsunamis, as demonstrated in the seismicity of the Sanriku coast, most recently in the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami.

See also

References

- "ria". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Cotton, C.A. (1956). "Rias Sensu Stricto and Sensu Lato". The Geographical Journal. 122 (3): 360–364. doi:10.2307/1791018. JSTOR 1791018.

- Goudie, A. (2004) Encyclopedia of Geomorphology. Routledge. London, England.

- Bird, E.C.F. (2008) Coastal Geomorphology: An Introduction, 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. West Sussex, England.

- Gulliver, F.P. (1899). "Shoreline Topography". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 34 (8): 151–258. doi:10.2307/20020880. JSTOR 20020880.

- Michael J. Kennish; Hans W. Paerl (15 June 2010). Coastal Lagoons: Critical Habitats of Environmental Change. CRC Press. pp. 361–. ISBN 978-1-4200-8831-1.

Further reading

- Perillo, Gerardo, Geomorphology and Sedimentology of Estuaries, Volume 53. pp. 17–47. Elsevier Science (1995) ISBN 9780080532493

- von Richthofen, F. Fuhrer fur Forschungsreisende ("Guide for Explorers"), pp. 308–310. Berlin, Oppenheim (1886)