Dubin–Johnson syndrome

Dubin–Johnson syndrome is a rare, autosomal recessive, benign disorder that causes an isolated increase of conjugated bilirubin in the serum. Classically, the condition causes a black liver due to the deposition of a pigment similar to melanin.[2] This condition is associated with a defect in the ability of hepatocytes to secrete conjugated bilirubin into the bile, and is similar to Rotor syndrome. It is usually asymptomatic, but may be diagnosed in early infancy based on laboratory tests. No treatment is usually needed.[2]

| Dubin–Johnson syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia[1] |

| |

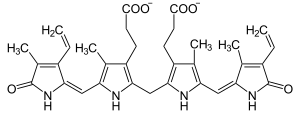

| Bilirubin | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, hepatology |

| Symptoms | Jaundice, otherwise asymptomatic |

| Prognosis | Good |

Signs and symptoms

Around 80 to 99% of people with Dubin–Johnson syndrome have jaundice,[3][4] abnormal urinary color, biliary tract abnormality, and conjugated bilirubinemia.[4] Around 30 to 79% of people with the disorder have abnormality of the gastric mucosa.[4] Other rare symptoms include fever and fatigue.[3]

Pathophysiology

The conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is a result of defective endogenous and exogenous transfer of anionic conjugates from hepatocytes into bile.[5] Impaired biliary excretion of bilirubin glucuronides is due to a mutation in the canalicular multiple drug-resistance protein 2 (MRP2). A darkly pigmented liver is due to polymerized epinephrine metabolites, not bilirubin.[6]

Dubin–Johnson syndrome is due to a defect in the multiple drug resistance protein 2 gene (ABCC2), located on chromosome 10.[2] It is an autosomal recessive disease and is likely due to a loss of function mutation, since the mutation affects the cytoplasmic/binding domain.

Diagnosis

A hallmark of Dubin–Johnson syndrome is the unusual ratio between the byproducts of heme biosynthesis:

- Unaffected subjects have a coproporphyrin III to coproporphyrin I ratio around 3–4:1.

- In patients with Dubin–Johnson syndrome, this ratio is inverted, with coproporphyrin I being 3–4 times higher than coproporphyrin III. Analysis of urine porphyrins shows a normal level of coproporphyrin, but the I isomer accounts for 80% of the total (normally 25%).

For the first two days of life, healthy neonates have ratios of urinary coproporphyrin similar to those seen in patients with Dubin–Johnson syndrome; by 10 days of life, however, these levels convert to the normal adult ratio.[7]

In post mortem autopsy, the liver will have a dark pink or black appearance due to pigment accumulation.

Plentiful canalicular multiple drug-resistant protein causes bilirubin transfer to bile canaliculi. An isoform of this protein is localized to the apical hepatocyte membrane, allowing transport of glucuronide and glutathione conjugates back into the blood. High levels of gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) help in diagnosing pathologies involving biliary obstruction.

Differentiation from Rotor syndrome

Dubin–Johnson syndrome is similar to Rotor syndrome, but can be differentiated by:

| Rotor syndrome | Dubin–Johnson syndrome | |

| Appearance of liver | normal histology and appearance | liver has black pigmentation |

| Gallbladder visualization | gallbladder can be visualized by oral cholecystogram | gallbladder cannot be visualized |

| Total urine coproporphyrin content | high with <70% being isomer 1 | normal with >80% being isomer 1 (normal urine contains more of isomer 3 than isomer 1) |

A test of MRP2 activity can also be done to differentiate between Dubin–Johnson syndrome and Rotor syndrome. The clearance of bromsulphthalein is used to determine this, the test for which is called bromsulphthalein clearance test. 100 units of BSP is injected intravenously and then the clearance. In case of Dubin–Johnson syndrome, clearance of bromsulphthalein will be within 90 minutes, while in case of Rotor syndrome, the clearance is slow, i.e., it takes more than 90 minutes for clearance.

Treatment

Dubin–Johnson syndrome is a benign condition and no treatment is required. However, it is important to recognize the condition so as not to confuse it with other hepatobiliary disorders associated with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia that require treatment or have a different prognosis.[8]

Prognosis

Prognosis is good, and treatment of this syndrome is usually unnecessary. Most patients are asymptomatic and have normal lifespans.[5] Some neonates present with cholestasis.[5] Hormonal contraceptives and pregnancy may lead to overt jaundice and icterus (yellowing of the eyes and skin).

History

Dubin–Johnson syndrome was first described in 1954 by two men—Dr. Frank Johnson, a military physician and researcher at the Veterans Administration and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington, DC, and Dr. Isadore Dubin, a Canadian pathologist then working alongside him.[9] Johnson had studied medicine at Howard University College of Medicine and faced substantial discrimination in his medical career, on account of being an African-American, and was even turned away from active duty during the Battle of the Bulge, despite being a first lieutenant and trained physician.[10] Later, during his internship, he was required to sleep in a tuberculosis sanitarium, as the hospital did not allow African-American physicians to live in the same residencies as white physicians, and he was prevented from rotating on several services, including general surgery.[10] These experiences, coupled with his inherent interest in chemistry, compelled him to pursue pathology, where he ultimately met Dubin and described this syndrome for the first time.

References

- "Dubin-Johnson syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Strassburg CP (2010). "Hyperbilirubinemia syndromes (Gilbert-Meulengracht, Crigler-Najjar, Dubin-Johnson, and Rotor syndrome)". Best Practice & Research: Clinical Gastroenterology. 24 (5): 555–571. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2010.07.007. PMID 20955959.

- Gensler, Ryan; Delp, Dean; Rabinowitz, Simon S. (2020). "Dubin Johnson Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 2016-04-25. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- "Dubin-Johnson syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- Suzanne M Carter, MS Dubin–Johnson Syndrome at eMedicine

- Kumar, Vinay (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology. Elsevier. p. 639.

- Rocchi E, Balli F, Gibertini P, et al. (June 1984). "Coproporphyrin excretion in healthy newborn babies". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 3 (3): 402–7. doi:10.1097/00005176-198406000-00017. hdl:11380/612304. PMID 6737185.

- Up-to-date: "Inherited disorders associated with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia"

- Dubin, IN; Johnson, F (September 1954). "Chronic idiopathic jaundice with unidentified pigment in liver cells; a new clinicopathologic entity with a report of 12 cases". Medicine (Baltimore). 33 (3): 155–198. doi:10.1097/00005792-195409000-00001. PMID 13193360.

- Kennedy, Charles Stuart (1992). Dr. Frank B. Johnson Oral History Interview. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Oral History Program. Archived by the Internet Archive, retrieved March 24, 2016.

External links

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome at MedlinePlus.gov

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome at Medline Plus encyclopedia

- Dubin–Johnson syndrome at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases