Dystrophaeus

Dystrophaeus is an extinct genus of sauropod dinosaur. Its type and only species is Dystrophaeus viaemalae, named by Edward Drinker Cope in 1877. Its fossils were found in the Tidwell Member of the Morrison Formation of Utah. Due to the fragmentary condition of its only known specimen, the affinities of Dystrophaeus are uncertain, although excavations carried out at the discovery site since 1989 have uncovered more of the original specimen and hold the potential for an improved understanding of the taxon.

| Dystrophaeus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Metacarpals from the holotype (USNM 2364) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Genus: | †Dystrophaeus Cope, 1877 |

| Species: | †D. viaemalae |

| Binomial name | |

| †Dystrophaeus viaemalae Cope, 1877 | |

Fossil record

Dystrophaeus viaemalae is known from a single fragmentary specimen, the holotype USNM 2364. The specimen initially consisted of a partial dorsal vertebra, a partial scapula, a nearly complete ulna,[lower-alpha 1] a partial radius, and three metacarpals.[1] More recent excavations have discovered additional parts of the same specimen, including a phalanx,[2] teeth, and additional vertebrae from the back and tail.[3] The specimen was found in the Tidwell Member of the Morrison Formation and is approximately 158 million years old, making it the oldest species of sauropod from the Morrison Formation by several million years.[3]

Description

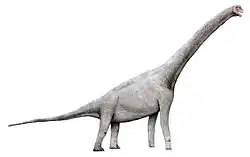

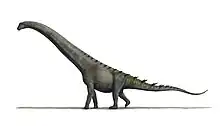

Not much can be surmised due to the fragmentary nature and uncertain phylogenetic position of Dystrophaeus.[4][1] As a sauropod, Dystrophaeus would have been a large, long-necked herbivore. It would have been of moderate size for a sauropod; it may have been approximately 13 metres (43 ft) long,[lower-alpha 2] with a mass of roughly 7–12 tonnes (7.7–13.2 short tons).[lower-alpha 3] The ulna of the only known specimen is 76.4 centimetres (30.1 in) long;[8] for comparison, the ulna of the holotype of Camarasaurus lewisi is 77.5 centimetres (30.5 in).[9] The scapula bears a subtriangular projection on the base of the scapular blade, which Tschopp et al.'s analysis found to be an autapomorphy of the taxon, though this trait also occurs in various other sauropods.[1] The ulna is very slender, and the metacarpals are relatively short.[10]

History

Discovery and naming

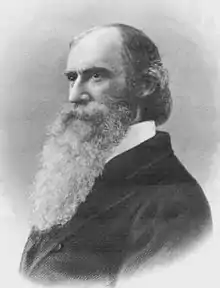

Few dinosaur fossils had been collected in the American West until the 1850s,[11] with expeditions by naturalists like Joseph Leidy and Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden in South Dakota and Montana finding fragmentary fossils, mostly teeth, from dinosaurs in 1855 and 1856.[11] The next discovery came accidentally in 1859 when while Captain John N. Macomb was leading a U.S. Army Engineers survey from Santa Fe to the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers, his crew camped south of what is now Moab, Utah.[12][4] In August, a geologist from the crew named John Strong Newberry, unearthed several large fossil bones in sandstone rocks elevated in a canyon wall near the camp.[12][4] Newberry successfully excavated several of the bones with several other crew members while using poor equipment, but several fossils remained in the sandstone rocks due to the team's time constraints of the expedition.[13][4] The fossils excavated consisted of only one partial skeleton, the holotype USNM 2364, which includes a 76.5 centimetres (30.1 in) long humerus, a possible ulna, a scapula, a partial radius, and some metacarpals. The specimen was from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation, and was notably from the older Tidwell Member of the Oxfordian,[4] and is one of the few dinosaurs known from the member.[4] The fossils were turned over to Joseph Leidy in Philadelphia, and later to Edward Drinker Cope, who described them in the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society in 1877. Cope named the remains Dystrophaeus viaemalae, the genus name means "coarse joint" from Greek dys, "bad", and stropheus, "joint", a reference to the pitted joint surfaces serving as an attachment for cartilage.[12] The specific name reads as Latin viae malae, "of the bad road", a reference to the various arduous routes taken to find, reach and salvage the remains.[12]

Rediscovery

Dystrophaeus received little attention besides its classification since before the 1970s until amateur Moab geologist Fran Barnes attempted to rediscover Newberry's original Dystrophaeus locality, eventually rediscovering the site in 1987.[4] The rediscovery was confirmed by David Gillette and in 2014 John Foster created the Dystrophaeus Project,[14] which launched another expedition to the site the same year to recover additional material left behind by the Macomb Expedition.[14][4] Another expedition was launched in 2017, the two recent expeditions recovering various elements including teeth, vertebrae, and additional limb bones, though many remain unprepared.[4]

Classification

The classification of Dystrophaeus has been rather confusing. Cope in 1877 merely concluded it was some Triassic dinosaur.[12] Henri-Émile Sauvage in 1882 understood it was a sauropod, assigning it to the Atlantosauridae. Othniel Charles Marsh however, in 1895 stated it belonged to the Stegosauridae. Friedrich von Huene, the first to determine it was of Jurassic age, in 1904 created a special family for it, the Dystrophaeidae, which he assumed to be herbivorous theropods.[8] Only in 1908 von Huene realised his mistake and classified it in the sauropod family Cetiosauridae, refining this in 1927 to the Cardiodontinae. Alfred Romer in 1966 put it in the Brachiosauridae, in a subfamily Cetiosaurinae.

More recently, an analysis by David Gillette concluded it was a member of the Diplodocidae.[2][15] Tschopp and colleagues included D. viaemalae in a phylogenetic analysis in 2015, and found its phylogenetic position to be highly unstable. They concluded that positions in Dicraeosauridae or Camarasauridae were equally well-supported, but that it was probably not a diplodocid, and concluded that further study was required to determine its affinities.[1] However, many researchers consider the taxon to be a nomen dubium.[1] Newer finds of Dystrophaeus have led paleontologist John Foster and colleagues to suggest it was most closely related to Macronarian or Eusauropod dinosaurs,[4] although much material has yet to be prepared.[4] According to Foster, the newly found caudal vertebrae rule out diplodocid affinities.[3]

Notes

- Initially misidentified as a humerus by Cope

- Paul (2016) estimated its length as 13 m (43 feet).[5] Holtz (2007) regarded its length as unknown.[6]

- Paul (2016) estimated its mass as 7 tonnes.[5] Foster estimated its mass as approximately 12,000 kg in 2003, based on comparison to diplodocids.[7] In 2020, no longer considering it to have affinities to diplodocids, he estimated its mass as approximately 10,000 kg.[3] Holtz, refraining from giving numerical estimates to avoid false precision, simply indicated it was about the size of an elephant.[6]

References

- Tschopp, Emanuel; Mateus, Octávio; Benson, Roger B. J. (2015-04-07). "A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". PeerJ. 3. doi:10.7717/peerj.857. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4393826.

- Gillette, D.D., 1996, "Origin and early evolution of the sauropod dinosaurs of North America -- the type locality and stratigraphic position of Dystrophaeus viaemalae Cope 1877", In: Huffman, A.C., Lund, W.R., and Godwin, L.H. (eds), Geology and resources of the Paradox Basin, Utah Geological Association Guidebook, 25: 313-324

- Foster, John Russell (2020). Jurassic West: the dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and their world. Life of the past (2 ed.). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-05158-5.

- Foster, J. R.; Irmis, R. B.; Trujillo, K. C.; McMullen, S. K.; Gillette, D. D. (2016). "Dystrophaeus viaemalae Cope from the basal Morrison Formation of Utah: Implications for the origin of eusauropods in North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts: 138.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-78684-190-2. OCLC 985402380.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Dinosaurs: the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- Foster, John R. (2003). "Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A.". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 23: 1–95. ISSN 1524-4156.

- von Huene, Friedrich (1904). "Dystrophaeus viaemalae Cope in neuer Beleuchtung". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Beilage-Band. 19: 319–333.

- McIntosh, John S; Miller, Wade E; Stadtman, Kenneth L; Gillette, David D (1996). "The osteology of Camarasaurus lewisi (Jensen, 1988)". Brigham Young University Geology Studies. 41: 73–115. ISSN 0068-1016.

- McIntosh, J. S. (1990). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (1 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 345–401.

- Breithaupt, B. H. (1999). The first discoveries of dinosaurs in the American West. Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah, 59-65.

- Cope, E. D. (1877). "On a dinosaurian from the Trias of Utah". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 16 (99): 579–584. JSTOR 982482.

- "Skeleton of dinosaur first unearthed 155 years ago now being excavated". KSTU. 2014-08-29. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- Foster, R. H. (2014). "The Dystrophaeus Project".

- Gillette, D.D., 1996, "Stratigraphic position of the sauropod Dystrophaeus viaemalae Cope and its evolutionary implications", In: Morales, Michael, editor, The continental Jurassic, Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 60: 59-68